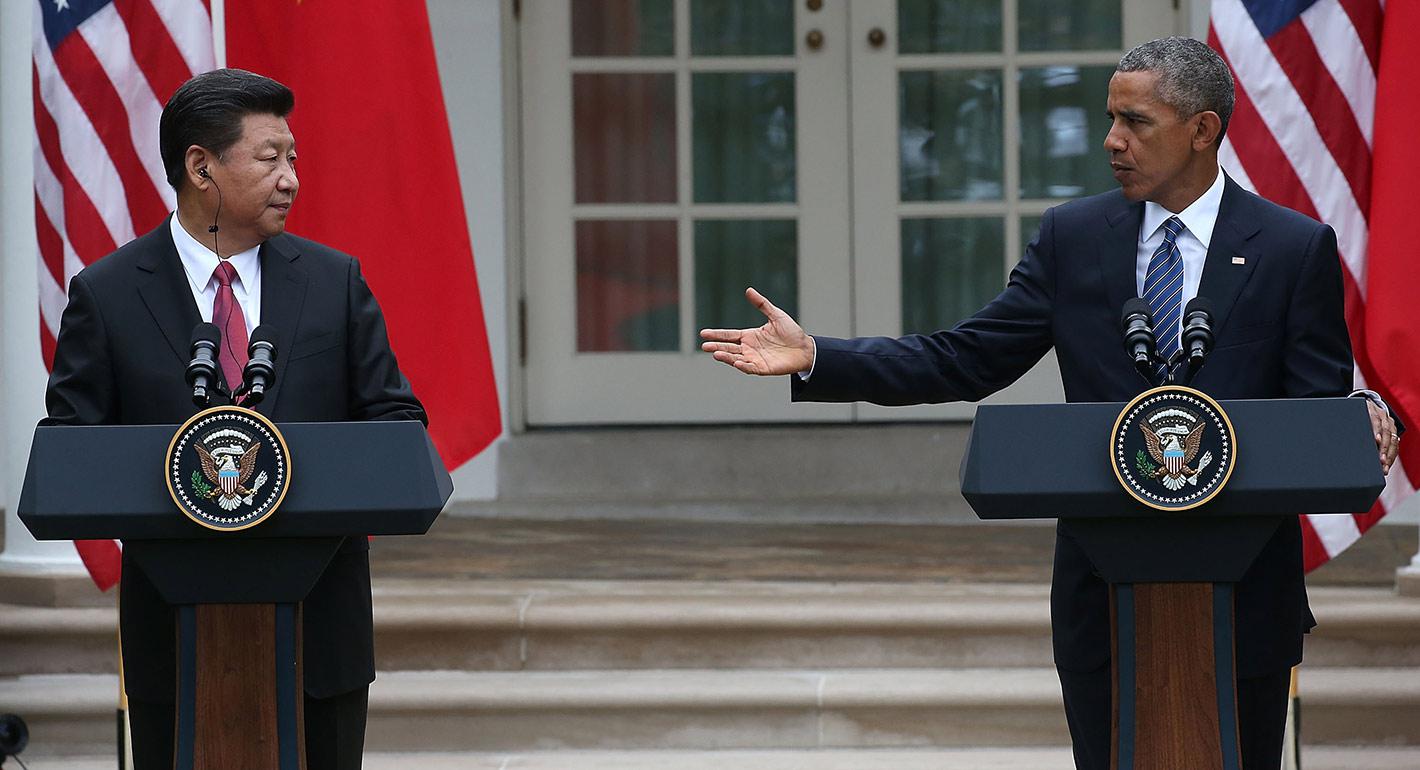

In September 2015, a bilateral summit between Chinese President Xi Jinping and then U.S. president Barack Obama laid the foundation for an international norm against cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property for commercial gain. After two days of meetings at the White House, Xi and Obama announced that China and the United States had reached an understanding not to “conduct or knowingly support cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property, including trade secrets or other confidential business information, with the intent of providing competitive advantages to companies or commercial sectors.” This common understanding marked the first time Xi or any other Chinese leader had recognized the U.S. position on the distinction between hacking for commercial purposes and hacking for national security purposes. It also paved the way for the 2015 G20 leaders’ communiqué on ICT-enabled theft of intellectual property, a landmark moment in diplomacy and a key milestone in the global effort to establish bounds of responsible state behavior in cyberspace.

Background

The 2015 Obama-Xi summit took place amid rising tensions between the United States and China. The United States had alleged that for years, Chinese state-sponsored hacking groups had conducted an aggressive and extensive campaign of cyber espionage—stealing hundreds of billions of dollars worth of intellectual property, trade secrets, and commercial data from Western firms, many of them American. The United States further alleged that the Chinese government was reinvesting this stolen intellectual property into its military capabilities, as well as sharing it with Chinese firms to improve the competitiveness of their products against western counterparts.

The United States took issue with this activity due to the distinction it drew between state-sponsored cyber espionage for commercial gain and state-sponsored cyber espionage for national security purposes. The former it saw as outside the boundaries of responsible state behavior, the latter it accepted as fair game. As Chinese commercial cyber espionage became more aggressive in the years leading up to 2015, the United States became more forceful in its efforts to name and shame the perpetrators of such activity. In 2014, the Department of Justice indicted Chinese military officers on charges of hacking and economic espionage, and by August 2015 the U.S. was reportedly preparing sanctions against Chinese companies and entities who had benefited from the cyber-enabled theft of American intellectual property.

Breakthrough Moment

Obama and Xi’s political commitment to renounce cyber espionage for commercial gain was a welcome breakthrough for the increasingly strained Sino-American relationship. Left unsaid at the White House was both leaders’ tacit recognition that state-sponsored hacking for national security purposes remained within the realm of expected behavior in the U.S.-China relationship. Nor did Xi or Obama elaborate on what they saw as the dividing line between hacking for national security and hacking for commercial gain.

Nevertheless, Xi’s commitment to restrain Chinese cyber-enabled economic espionage was an important diplomatic achievement for the United States, one that significantly advanced American efforts to solidify a global norm against such behavior. The understanding between Obama and Xi provided a model for bilateral negotiation with China on IP theft, which several American allies sought to replicate in the weeks that followed. Two months after the Obama-Xi Summit, the G20 Antalya leaders’ communiqué affirmed inter alia that “no country should conduct or support ICT-enabled theft of intellectual property, including trade secrets or other confidential business information, with the intent of providing competitive advantages to companies or commercial sectors.”

The Antalya communiqué was a landmark moment in cyber diplomacy; it represented a commitment of the world’s twenty largest economies—not all of whom were like-minded nations, and many of whom were economic competitors—to not engage in cyber-enabled economic espionage. Such breadth of participation in the agreement gave the commitment greater normative legitimacy than it would have otherwise enjoyed had it been agreed upon by a smaller group of like-minded nations.

It was also no accident that the language in the Antalya communiqué was almost identical to that issued by the White House in the wake of the Obama-Xi summit. Such a substantial international commitment on cyber-enabled commercial espionage would likely not have been achieved without the preceding U.S.-China bilateral understanding. An international norm was (and remains) the United States’ ultimate goal, but due to the sheer volume of intellectual property theft perpetrated by the Chinese government, a political commitment that excluded China would have disregarded the source, by some estimates, of over half of global state-sponsored economic espionage activity. Working bilaterally with Xi made a positive outcome on curbing Chinese intellectual property theft far more likely for the Obama administration than it could have hoped for in the G20. Once a bilateral commitment between the United States and China was achieved, the two countries’ unique leverage as global economic, cyber, and technological powers dramatically facilitated the adoption of the wider norm.

Looking Ahead

The United States and China’s adherence to their bilateral agreement remains critical to the continued strength and legitimacy of an international norm against cyber-enabled economic espionage. Unfortunately, Sino-American relations have devolved since 2015, and the United States has accused China of breaching the Obama-Xi common understanding. It may be the case, as some have argued, that China had no intention of adhering to its commitments to the United States or to the G20 over the long term, and instead endorsed a commitment against cyber-enabled economic espionage because it accelerated existing domestic efforts to root out corruption in the People’s Liberation Army and re-orient Chinese hacking methods to become more sophisticated and less noisy. Xi may have also seen his understanding with Obama as a personal commitment between two world leaders that expired upon the ascension of Donald Trump to the American presidency.

Alternatively, we may be witnessing the consequences of Obama and Xi’s failure to specifically articulate the distinction between hacking with the intent to provide competitive advantage and hacking with the intent to protect national security. Many emerging technologies are dual-use, meaning they have both civilian and military applications. Chinese leaders may view cyber espionage to steal such dual-use technology as an action taken for reasons of national security rather than economic competitiveness, circumventing China’s normative obligations. During Donald Trump’s administration, the United States also began to conflate economic security with national security in its rhetoric and policy toward China, further obfuscating the definition of cyber espionage for commercial advantage and creating additional justifications within China for new commercial cyber espionage efforts. Whatever its cause, the erosion of the Obama-Xi common understanding is a troubling development for the commitment against cyber-enabled economic espionage, which may struggle to evolve into a legitimate norm without steadfast American and Chinese support.