Introduction

There are ongoing debates in Western capitals and global media on whether China is experiencing a serious economic slowdown, whether the economy is on the verge of collapse, and how a collapse may impact the rest of the world.1 While prophecies of pending economic calamity may be dubious, China’s economic growth has certainly slowed and the economy is undergoing a major economic transition resulting from both domestic and geopolitical challenges. It’s also clear that due to China’s sheer weight in the global economy, effects of this transition will reverberate around the world. In fact, they are already evident in Africa, where China is the continent’s largest bilateral trade partner, a major provider of development finance, and an increasingly important source of foreign direct investment (FDI). Informed by the debate on China’s economic “slowdown,” this paper examines the state of China-Africa economic relations and identifies continuities and changes in five key areas: trade, investment, fiscal stabilization, renminbi (RMB) internationalization, and people-to-people ties. Some of the changes highlighted currently elude the radar of Western policy discourse and most media.

The analysis is underpinned by three important assumptions. First, the current situation in China—evidenced by a slowdown of growth, the changing performance of specific industries, and drastic changes in employment numbers—reflects transitory and, in some cases, anticipated changes as the country moves toward a new development model. China intends for this model to be characterized by “quality improvement,” reduced carbon emissions and increased environmental sustainability, innovation in high-tech industries, higher domestic demand, and narrowed regional and income disparities—all to reach the Vision 2035 goal of socialist modernization.2 Second, these economic shifts are largely policy-induced to respond to China’s domestic challenges, including its demographic transition, and to accelerate its post-pandemic recovery. These policies are also intended to respond to a more turbulent global environment—notably the increasingly adversarial relationship with the United States (and some U.S. allies, particularly in Europe) and shocks from the war in Ukraine—as well as to place more emphasis on strengthening relations with the Global South. Third, in the near term, while China may not be on course to achieve its famed double-digit growth rates of the 1980s to 2010s, its growth rates will likely be higher than those of nearly all the world’s ten largest economies, excluding India; the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that China will continue to experience growth rates of around 4 to 5 percent per annum.3

Based on the analysis, the paper concludes by outlining how policy directions within African countries and third-party countries, including the United States, could significantly affect how these trends in the China-Africa economic relationship unfold.

Trade

The African continent’s global trade realities have distinct Chinese characteristics. China is the continent’s largest bilateral trade partner, and the trade volumes are on a rising trend, reaching a historic high of $282 billion in 2023. But for China, Africa constitutes only 4.7 percent of its global trade. There is a massive imbalance in this commerce that sees China exporting more ($173 billion) to Africa than it imports ($109 billion) from Africa.4 As the Chinese economy recalibrates to adapt to domestic and geopolitical factors, several trends are increasingly evident in China-Africa trade relations.

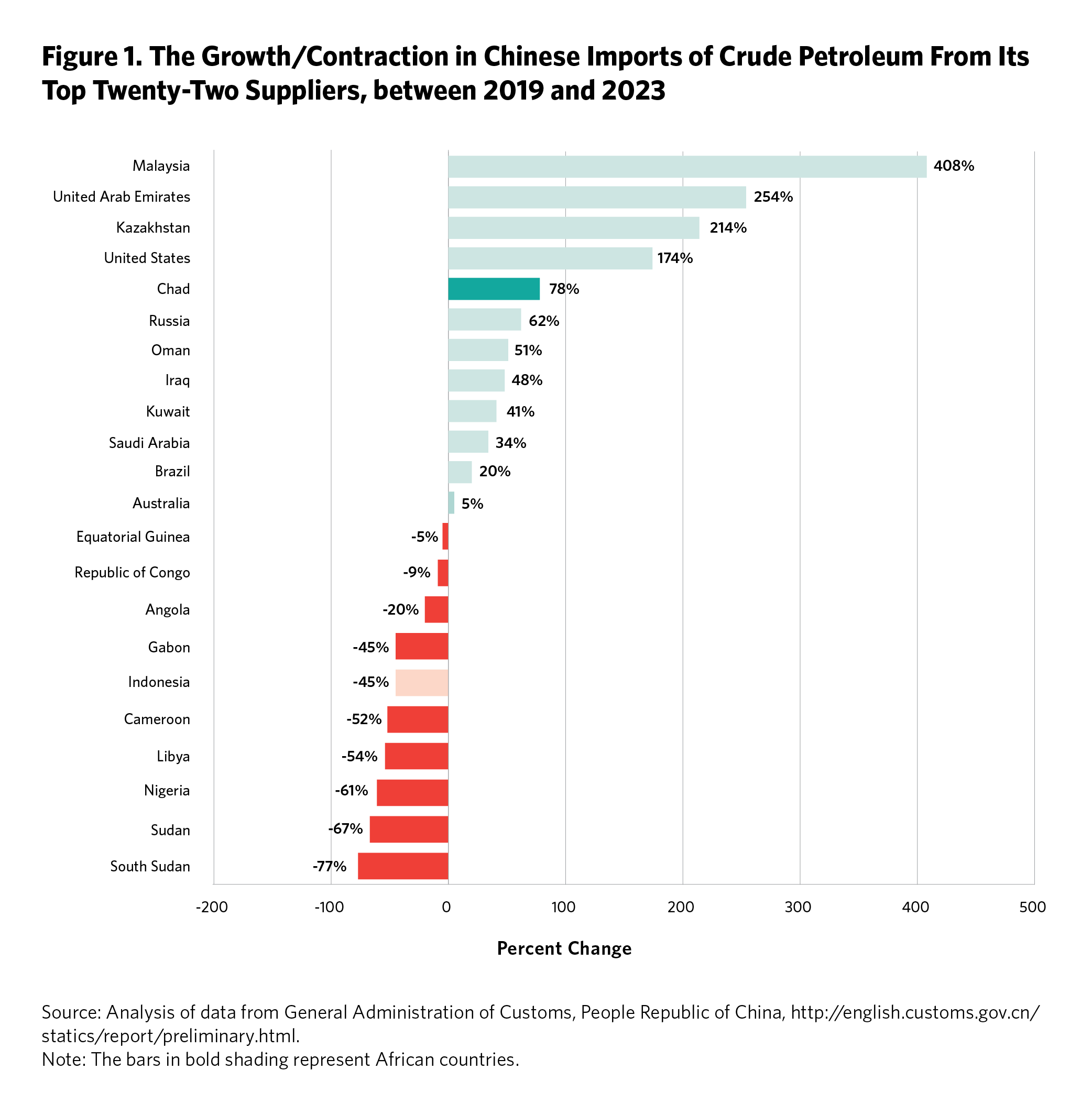

While African exports to China remain largely composed of unprocessed commodities, the exact composition of this export basket is changing. Specifically, oil imports from Africa are declining as China increasingly sources crude oil from the more predictable production infrastructure of Gulf Cooperation Council countries, Russia, and other countries in Asia. As Figure 1 shows, the value of crude oil imports from Russia and most Asian producers in 2023 increased from pre-pandemic levels in 2019. Worth noting is that imports increased by over 40 percent for nearly all of China’s top oil trade partners in Asia, with the exception of Iran, whose oil is transshipped via countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Malaysia. Dramatic increases can be seen in China’s imports of oil from the UAE (254 percent), Malaysia (408 percent), Kazakhstan (214 percent), and Kuwait (41 percent).

By contrast, China is buying and consuming less crude oil from Africa. With the exception of Chad, which saw a 78-percent increase in the value of its oil exports to China between 2019 and 2023, all of the other eight major African oil producers have earned much less than they did before the pandemic. The case of Angola is particularly striking. In 2010, Angola was the world’s second-largest exporter of oil to China, after Saudi Arabia.5 By 2023, Angola had been bumped to number eight on this ranking of oil suppliers to China (Figure 1). Other noteworthy cases include South Sudan, Sudan, and Nigeria, which have all seen serious declines of 77 percent, 67 percent, and 61 percent, respectively, in their hydrocarbons trade with China. Even though China’s consumption of oil is growing, the supplies are being increasingly sourced from non-African producers, particularly Russia and countries in the Middle East.

In mineral and metal trade, however, African exports to China are on a rapid ascent, reaching nearly $50 billion in 2021 from $15 billion in 2010.6 Moreover, Chinese investments are beginning to cover not only the extraction of ores but also the refining and processing of them on the continent. Recently announced refining projects by Chinese companies include a $300 million lithium processing plant, opened in Zimbabwe in June 2023 by Prospect Lithium Zimbabwe; a $250 million lithium processing plant, opened in October 2023 in Nigeria by Ganfeng Lithium Industry Limited; and others, including in Morocco.7 These trends in the fossil fuel and metals trade are crucial for a continent with more than ten major oil producers and twenty mineral producers.

Another trade-related trend that could further shape the Africa-China relationship is a continued expansion of semiprocessed agriculture exports from African countries to reduce the continent’s trade deficit. During successive sessions of the Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) since 2018, China has committed to the opening of “green lanes” to fast-track the inspection and quarantine process for African agriculture exports to China.8 While the overwhelming trade in agriculture is composed of raw commodities, there are notable instances of individual African countries attempting to buck this trend. After years of effort to meet stringent sanitary and phytosanitary standards, Kenyan farmers finally began exporting flash-frozen avocados to China in August 2022. Around 30 percent of Kenya’s avocados are exported to China today.9 Similarly, Namibia began exporting beef to China in 2019, and Ethiopian and Rwandan coffee is now being sold to Chinese retailers using e-commerce platforms. These developments involving individual commodities and country examples have not yet shown up in significant ways in aggregate Africa-China export data, but they indicate ripples that in time could constitute a sea of change for agricultural exports in a continent where the sector contributes about 17 percent of GDP and more nearly 50 percent of employment.10

Finally, the role of Chinese e-commerce platforms will increasingly characterize two-way China-Africa trade. Platforms such as Kilimall, Alibaba Group’s Tmall, JD.com, and Kikuu are providing a virtual doorway for African suppliers into the world’s largest e-commerce market. Kilimall, for instance, is an e-commerce platform started in Kenya in 2014; and with most of its supply chain in China, it provides e-commerce transaction, mobile payment, and cross-border logistics services for over 10 million African users, mainly from Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda.11 Through live-streaming events on these e-commerce platforms during shopping festivals in China, sales of African goods pick up. During one such festival in China in May 2022, the sales of Kenyan black tea and Ethiopian coffee surged 409 percent and 143 percent compared to 2021 figures.12

Investments

China has largely reduced its investments from public sector financiers in Africa’s infrastructure during the past five years, but its officials stress that this is hardly a permanent retreat. In fact, at the 2023 BRICS Summit in South Africa, Chinese officials highlighted an intention to cooperate with African countries on industrialization, which would be both a continuation and a nuanced shift of previous policy.13 Because infrastructure in some African countries has been largely underutilized, China hopes to boost productivity by adding industrial components to infrastructure projects. In China’s experience, the synergy between industrialization and infrastructure has proven to be essential in driving sustainable economic growth and social transformation. Thus, the shift from infrastructure to industrialization is just placing an emphasis on the other side of the same coin. Infrastructure and industrialization may form a bifurcated and more comprehensive approach in the coming years. China’s policy shift represents a continued commitment to Africa’s development, but with a new focus on the continent’s current macroeconomic situation.

However, this industrialization approach will be somewhat distinct from the infrastructure one, as most Chinese industrial investments will come from private companies. The manufacturing sector in China is dominated by numerous small and medium-sized enterprises that fiercely compete in the global market. They are eager to expand into African markets for multiple reasons.

First, as the labor costs in China and Southeast Asia continue to rise, some Chinese investors may consider relocating production bases to Africa, where wages are much lower.14 But due to deficient infrastructure and weak support along the supply chain, offshore manufacturing in Africa remains small. After decades-long experiments, only a few Chinese manufacturers of low-quality garments and footwear are able to export from African countries. Even when geopolitical tensions have led some Chinese manufacturers to accelerate efforts to relocate outside of China, these outward bound investments have been destined for countries in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Europe as gateways to the U.S. market; Africa has not benefited from these shifts because it is not as well integrated into global manufacturing supply chains.

Second, Chinese manufacturers who produce for African consumers have been prospering even during the COVID pandemic. From cement, plastics, and pharmaceutics to cosmetics, cell phones, and electric cars, Chinese investors have recently set up a wide range of factories on the continent to meet the demand of an expanding African middle class. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) further presents huge potential for this category of investors.

Last but not least, Chinese investors are looking to foster supply chains by adding processing capacity to Africa’s agricultural and extractive sectors. Advanced processing of natural resources on the African continent is motivated by both the priorities of African governments and by China’s economic security concerns amid a more turbulent geopolitical environment. China will gradually help Africa build up comprehensive industrial capacity in the coming years.

In sum, the reduced flows of Chinese public investments in African infrastructure over the past five years will be offset by increased flows in private investments mostly in industrialization projects.

Fiscal Stabilization

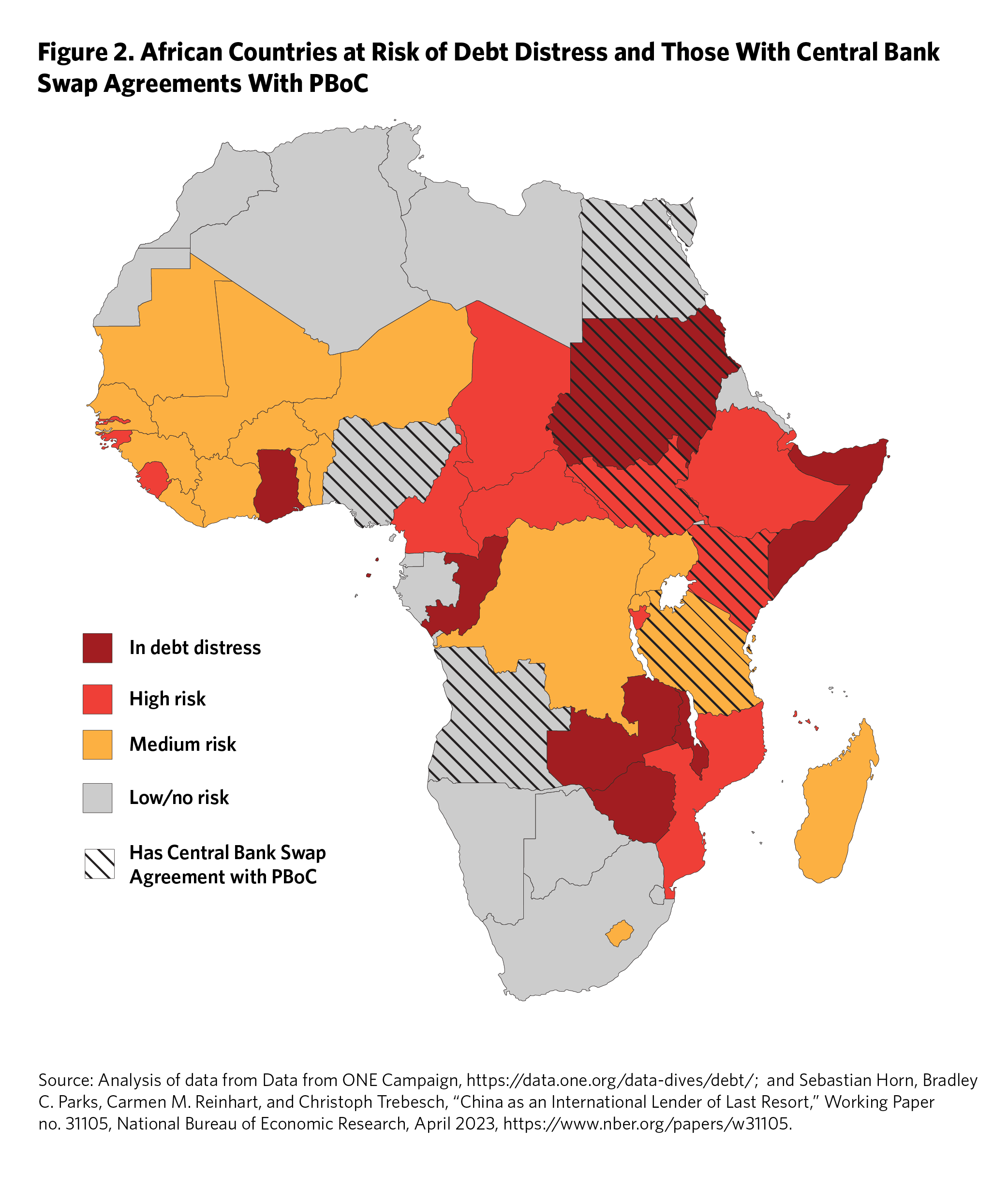

As many African countries find themselves at risk of a debt crisis, Chinese banks will focus on fiscal stabilization rather than launching new projects. There are currently twenty-one African countries that are in, or at high risk of, debt distress according to the IMF (see Figure 2), and Chinese public and private creditors own about 13 percent of this debt while private creditors elsewhere own around 49 percent.15 The negotiations on debt restructuring and relief between China and a handful of debt-stricken countries—such as Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Zambia—will likely continue for several years. Nonetheless, the agreement reached by Zambia and its official creditors, including China, under the G20 Common Framework in June 2023 is viewed as a milestone for the Chinese approach of debt restructuring, which favors repayment extension instead of haircut relief.16 This precedent will not only facilitate debt negotiations with other African countries, but also give China the confidence to work within the multilateral framework while keeping its own traditions and principles. The restructuring solution in Zambia, which all stakeholders found acceptable, is expected to open a new era for traditional and emerging creditors to collaborate after years of struggling.

Based on its experiences and lessons learned from debt restructuring, China will certainly revise its lending strategy in Africa. This does not necessarily mean a reduction in loans, as Africa still has huge demand and potential for development financing. However, the destinations, sectors, and modality of Chinese financing will need to be adapted to fit the new circumstances in the evolving African market. Corresponding to the shift in focus from infrastructure to industrialization, China may increase funding for industrial projects via equity investment platforms such as the China-Africa Development Fund and the China-Africa Industrial Capacity Cooperation Fund.

Finally, China is emerging as a prominent lender of last resort by issuing rescue loans to countries in debt distress. This role entails providing emergency liquidity support in the mold of short-term loans that the IMF provides to ease a country’s balance of payments crisis. One paper finds that Chinese state-owned banks and companies provided rescue loans or balance of payments support—which entail U.S. dollar credit lines that allow recipients to service external debt, increase reserves, or finance general budgetary expenditures—worth $70 billion to thirteen low- and middle-income economies in debt distress between 2000 and 2021.17 The bailout lending total is higher, according to the paper, when the drawdowns of central bank currency swap lines, worth another $240 billion, are included in the total (although these swap lines are officially meant to increase bilateral trade and facilitate trade settlement in local currencies; see the “RMB Internationalization” section below). In total, seven African countries have received such bailout loans. These bailouts, particularly the bridge loans, are much smaller than the IMF’s global lending portfolio and dwarfed by the sweeping international U.S. dollar liquidity support extended by the U.S. Federal Reserve since 2007, primarily to advanced economies. An important area to watch going forward will be how many other African countries secure such emergency liquidity support, given the large number of countries in debt distress.

RMB Internationalization

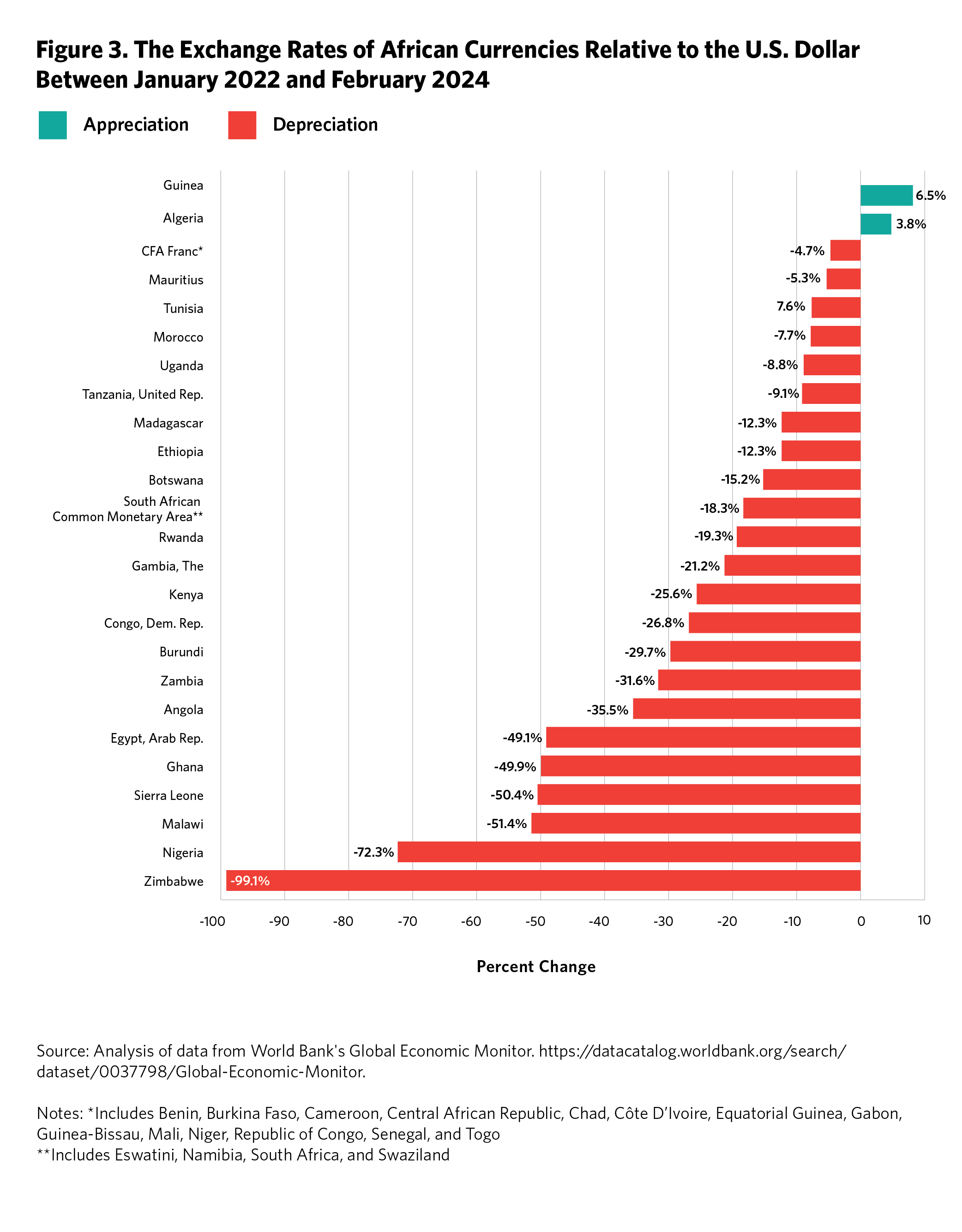

The confluence of China’s efforts to navigate a more turbulent global economy and the desperation in African countries for a remedy to their severe foreign exchange pressures could advance aspects of China’s long-term objective to increase international use of its currency, the renminbi. Presently, most cross-border transactions between China and African countries are conducted in U.S. dollars, including trade settlements, development finance, and FDI. The use of U.S. dollar and associated payments systems both integrates these countries into the existing global financial architecture and exposes them to external volatilities. Consequently, from January 2022 (when the U.S. Federal Reserve signaled plans to raise interest rates) to February 2024, the average currency depreciation for African countries was nearly 19 percent, with significant variations (see Figure 3). According to the IMF, these currency depreciations were mostly driven by external factors, including interest rate hikes in the United States that “pushed investors away from the region towards safer and higher paying US treasury bonds,” the reduction in demand for Africa’s exports, and the war in Ukraine that pushed up energy and food import prices.18

In the near term, the RMB is unlikely to become a major reserve currency for African countries and indeed the rest of the world due to the Chinese government’s unwillingness to fully liberalize the country’s capital account. However, a growing number of experts recognize that China can strengthen the RMB’s international role through (1) its use in China’s foreign trade transactions and other payments and (2) policy supports including central bank currency swaps and denomination of policy loans in RMB.19 In other words, even if the RMB does not meet what analysts Gerard Di Pippo and Andrea Leonard Palazzi refer to as a “high threshold of internationalization” (in other words, to become a premier global reserve currency on par with the U.S. dollar), it is achieving a low threshold of internationalization (in other words, its stature as a currency for bilateral transactions is growing).20 It is within the low threshold of internationalization that there are areas where the RMB may play an increasing role in Africa-China financial relations.

One domain where the RMB’s role could grow is in trade invoicing and settlement between African countries and China. Within the African continent, the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) is a notable effort underway to reduce the acute demand for foreign exchange by increasing the convertibility of local currencies in intra-African trade.21 Established by the Africa Export-Import Bank, PAPSS is a platform that works in conjunction with African central bank systems to provide a payment and settlement service to facilitate cross-border financial transactions using local currencies within the African continent. In other words, PAPSS aims to allow more than forty African currencies to be convertible for transactions among commercial banks and payment service providers within the continent without having to rely on intermediary currencies, such as dollars, euros, or pounds.22 By removing the need for this conversion process, PAPSS could, in the long run, substantially reduce some of the acute demand for foreign exchange, at least for cross-border payments, and also lessen exposure to the associated financial volatilities. This rollout of PAPSS points to the continent’s interest in solutions to ease cross-border financial payments and provides a potentially receptive environment for Chinese efforts to internationalize the RMB.

At the same time, recent geopolitical tensions are accelerating China’s efforts to reduce the exposure of its international trade and payments. In particular, China is seeking to reduce the exposure of its cross-border transactions to the U.S. dollar and will continue to do so if trade tensions and other relations with the United States continue to deteriorate. The wide-ranging Western sanctions on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine, especially Russia’s ejection from dollar and euro payment networks, have strengthened China’s resolve to avoid a similar fate in the event of a major fallout with the West. This means that China is very motivated to increase the global uptake of services provided by the financial and payments infrastructure it has been steadily constructing over the years. Consequently, the share of the RMB has been growing in China’s cross-border trade, reaching 49 percent in the second quarter of 2023.23 Russia is now relying heavily on both the RMB and the ruble for its bilateral trade with China. Several other countries—from Bangladesh and Brazil to Saudi Arabia and Thailand—are setting up mechanisms to facilitate use of the RMB in cross-border trade payments involving China.24 A key area to watch, therefore, is whether the RMB becomes more prominent in China’s merchandise trade with African countries.

Another area in which international use of the RMB may increase relates to bilateral currency swap agreements. Since 2008, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has signed bilateral currency swap agreements with central banks across at least thirty-nine countries, including four African countries.25 These currency swap lines aim to deepen bilateral trade by supplying trade credit to local commercial banks of the partner country, allowing direct trade settlement using the RMB and reducing the negative effects of exchange rate volatility.26

While the uptake and actual use of these RMB swap lines has been limited, changes could be on the horizon. For example, in 2018, the Central Bank of Nigeria signed its first bilateral currency swap agreement with the PBOC worth about $2.4 billion (or 15 billion yuan or 720 billion naira). The swap line was renewed in April 2021 and was up for another renewal in April 2024 but there are no updates yet on its status. However, implementation of the line has been challenging due to Nigeria’s trade deficit with China—Nigeria imports more than it exports, demand for the RMB is limited, and the $2.4 billion involved in the exchange is a mere 2 percent of the $124 billion bilateral trade between the two countries between 2018 and 2023.27 More recently, Nigerian lawmakers have called on the country’s central bank to revive this swap line with the PBOC, adopt the Chinese yuan as an official foreign exchange reserve currency alongside others, and consider the Chinese yuan as an alternative trading currency due to the steep decline in the value of Nigeria’s naira against the U.S. dollar and other major currencies.28 It is worth tracking the nature of further action that Nigerian authorities take on this front and whether the more than a dozen African countries experiencing foreign exchange shortages follow Nigeria’s steps.

Finally, there is demonstrated interest to denote, in RMB, policy loans issued by new multilateral institutions with strong Chinese participation to various countries in the Global South. For instance, the New Development Bank (NDB) in Shanghai, dubbed the “BRICS Bank,” issued its first South African rand bonds in August 2023. An important outcome of the 2023 BRICS Summit in South Africa was a commitment to increase use of the currencies of BRICS countries—including the Brazilian real, Indian rupee, and South African rand—to denominate sovereign loans. Specifically, the NDB aims to increase the share of its lending in members’ local currencies to 30 percent of the total portfolio from 20 percent in 2023.29 In some respects, these efforts to issue non–U.S. dollar loans will aim to encourage the use of infrastructure that China has built out over the past decade—such as the establishment of deeper and liquid capital markets in Hong Kong and Shanghai and the setting up of RMB clearing houses, including three in Africa. Similarly, during the Belt and Road Forum in December 2023, the China Development Bank, a state policy lender, signed RMB-denominated loan contracts with Malaysia’s Maybank, Egypt’s central bank, and BBVA Peru to support Belt and Road Initiative projects. An important area to watch going forward will be how many sovereign loans to African countries from Chinese policy banks are denominated in RMB.

Overall, the frequency of shocks, rising uncertainty, and geopolitical tensions in the global economy could incentivize both China and a significant number of African countries to consider use of the existing non–U.S. dollar payments’ infrastructure that China has set up over the past decade and a half, since the 2008 financial crisis.

People-to-People Ties

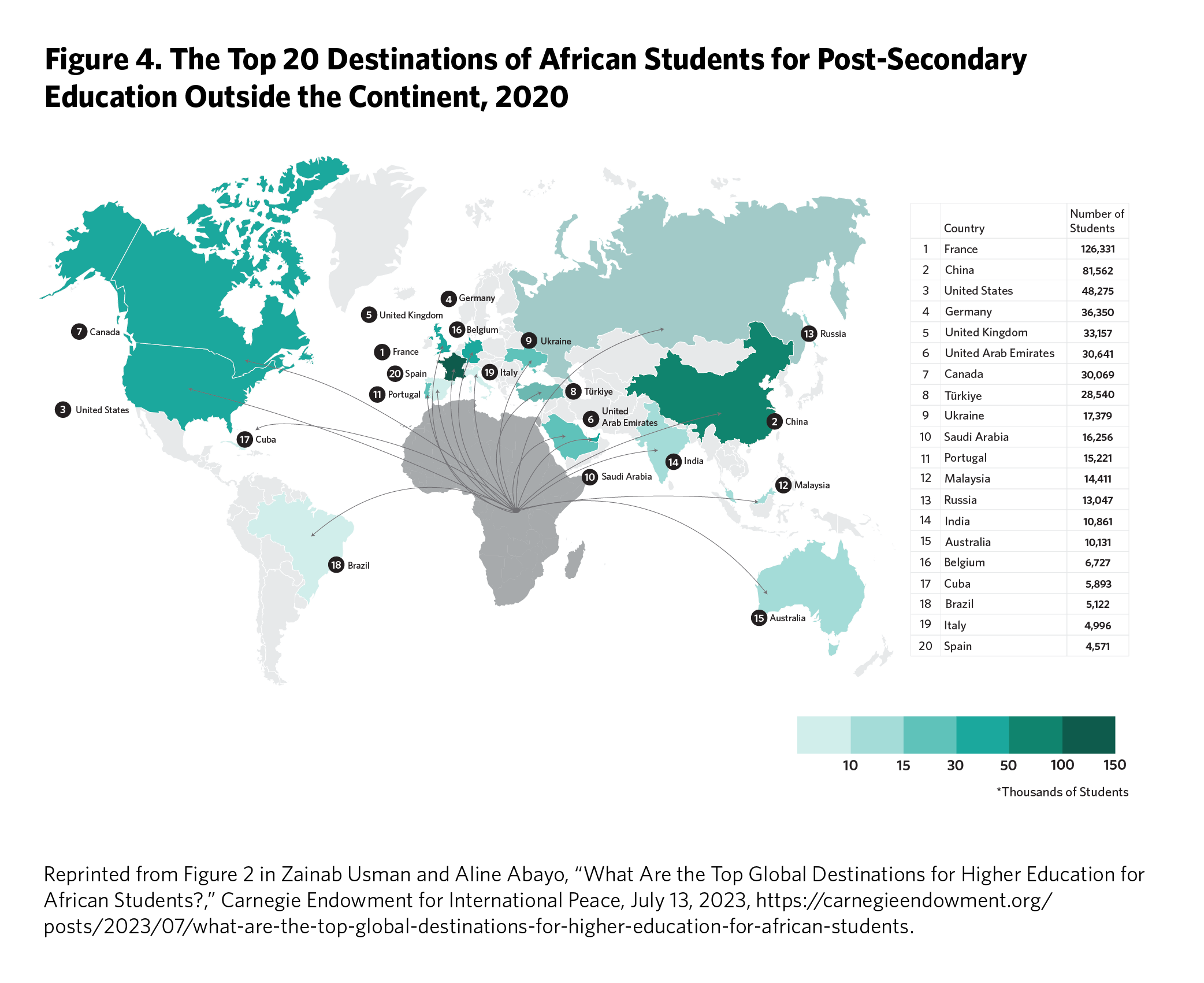

Higher education, media, and culture exchanges between China and Africa—with implications for skills building, migration, and soft power—are evolving as both regions settle into a post-pandemic normal. Chinese universities have been gaining popularity among African students thanks to the offering of scholarships as well as China’s growing reputation in technology and development.30 Therefore, as Figure 4 shows, China is the second-most popular destination for Africans seeking higher education abroad, with roughly 81,600 students; France is the most popular (126,300 students) and the United States is the third-most popular (48,300 students). However, China’s immigration policy is much tighter than the policies in European and North American countries. Therefore, most Africans studying in China tend to return home upon the completion of their studies instead of staying abroad, significantly reducing the prospects of “brain drain” for Africa.

China-Africa educational institutions are also maintaining strong collaboration. Sixty-one Confucius Institutes and forty-eight programs have been established in forty-eight African countries as of 2021. Additionally, China has supported over thirty African universities to set up departments or programs to study Chinese language. Luban Workshops in Djibouti, Egypt, Kenya, and South Africa have provided Chinese-style vocational training to African technicians, even when international travel has been restricted due to the COVID pandemic.31 Conversely, universities in China have added new courses for African languages, such as Amharic, Malagasy, and Zulu. Furthermore, the Plan for China-Africa Cooperation on Talent Development, announced in August 2023, has pledged to train 500 principals and high-calibre teachers of vocational colleges every year, as well as 10,000 technical personnel with both Chinese language and vocational skills for Africa. The number of cooperating Chinese and African universities will be increased from 20+20 to 50+50.32 However, there are occasionally reports about African students’ complaints related to Chinese teachers’ English proficiency, internship and employment opportunities, as well as administrative services.33 If the education quality does not improve, the quantitative growth in cooperating universities may not be sustainable.

Media and cultural exchanges between African countries and China have increased since the start of the pandemic, largely due to the use of digital technologies. The Chinese cable television operator StarTimes provided 13 million subscribers in Africa with programs in eleven languages as of November 2021.34 TikTok, cell phone maker Transsion, and other Chinese internet companies greatly boost the formation of Africa’s mobile media sphere. Chinese and African entertainment industries have been deepening their collaboration as well, with the joint production and broadcasting of movies and television series. Two notable series, Welcome to Milele Village (2023) and Ebola Fighters (2021), depicted Chinese medical teams in Africa and gained popularity among Chinese audiences. Soccer players from Angola, Cameroon, Ghana, and Nigeria have joined clubs in China’s Premier league and A-level league. Chinese tourists are now also interested in taking historical tours and immersing themselves in African culture, as well as exploring the country’s natural landscape. A number of African countries, including most recently Egypt, Mauritius, Morocco, and Tunisia, have been providing visa-free or visa-on-arrival entries to Chinese visitors to foster tourism.35 Echoing the movement, China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism has listed thirty-four African countries as destinations for group tours.36

Conclusion

China’s economic growth is slowing from the double digits of previous decades as policymakers steer the economy toward a more high-tech, consumption-oriented, and environmentally sustainable growth model with reduced exposure to geopolitical shocks. And this economic transition will increasingly have implications for China’s international economic relations with the rest of the world. As discussed above, across the five domains of China’s economic engagement with Africa—trade, investment, fiscal stabilization, RMB internationalization, and people-to-people ties—both strong continuities and changes are evident. But this engagement is not happening in a vacuum. Policy directions within African countries and third parties such as the United States will greatly shape how these changes in the China-Africa relationship continue to unfold.

The changing patterns of trade between African countries and China will be shaped by policies in both advanced economies and African countries themselves. Rising barriers to market access in advanced economies are likely to push African countries further into the embrace of China. Between 2021 and 2024, the administration of U.S. President Joe Biden has suspended a record eight African countries from the U.S. trade preference program, the African Growth and Opportunity Act. Meanwhile, the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which began its initial transitional phase in October 2023, could make it even more difficult for African manufacturers to export to the European market and reduce the continent’s GDP by up to $25 billion.37 Although individual European countries like France seek to expand their trade with Anglophone African countries,38 for instance, and the United Kingdom recently signed a trade deal with Kenya,39 this may not be sufficient to offset the wide-ranging impacts of market-restricting policies like the CBAM. Furthermore, growing China-Africa trade volumes will continue to be characterized by trade deficits. To address these deficits, African countries need to make a concerted effort to diversify their exports to China. Important steps to take include implementing the AfCFTA to create regional value chains, utilizing trade preference programs particularly the green lanes initiative—as Kenya and Namibia are doing—to export semi-processed agriculture produce to China and emulating the Indonesian approach to pressure Chinese companies to invest in the refining and processing of minerals in African countries.

As Chinese investments in Africa shift from infrastructure-oriented projects toward industrialization-oriented projects, African policy responses and the ability of Western countries to fill infrastructure financing gaps will be crucial. Chinese FDI flows for processing and manufacturing in various sectors—whether related to agriculture, minerals and metals, construction material, or apparel—are contingent on requirements in the domestic business environment that are within the remit of African governments. Basic requirements include the availability of affordable and reliable electricity, good transportation networks, skilled local workers, security, and the ability to compel Chinese companies to enter into joint ventures with local African firms for technology transfer. Whether the United States and its allies in Europe and Japan can step into the space being vacated by Chinese policy banks to provide infrastructure financing in Africa is an open question. Implementation of the Lobito Corridor project, a signature initiative of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), will test the G7’s commitment to the scaling up of infrastructure investments in Africa. Whether the United States continues to prioritize the PGII by ensuring the program’s continuity or incorporating new infrastructure projects remains to be seen—especially if a new U.S. administration comes into office in January 2025.

Expansion of China’s rescue-lending efforts and internationalization of the RMB in Africa are significantly dependent on African countries’ own demand for and uptake of these initiatives. Will a growing number of African countries look to China, as an alternative to the IMF, for emergency liquidity support as their ability to finance imports diminish due to fiscal crises? Will there be a growing appetite among African countries for more central bank currency swap lines with the PBOC, and will there be increased drawdowns of yuan reserves? As African countries struggle to find scarce foreign exchange resources to settle and invoice their trade, will they follow the trend among some Asian countries in using the RMB for their bilateral trade with China? The answer to these questions may lie largely in whether the United States and its allies in Europe will provide sufficient measures to support African countries to overcome the latest bout of debt distress and fiscal crises.

Finally, China’s loosening of pandemic-era travel restrictions and the phenomenon of digitalization will accelerate the increasing trend of people-to-people exchanges with African countries in higher education, media, and culture. Developments in China’s immigration policy will be important to track as it begins to roll out visa-free travel for a select number of European and Asian countries. The hardening of visa regimes in Canada, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, and other Western countries will also be important to monitor, as it could affect these countries’ historically robust people-to-people exchanges with African countries.

Notes

1 For instance, see Adam S. Posen, “The End of China’s Economic Miracle: How Beijing’s Struggles Could Be an Opportunity for Washington,” Foreign Affairs, August 2, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/end-china-economic-miracle-beijing-washington; “China Starts the Lunar New Year With an Economic Hangover: Can Xi Jinping Pull the Country Out of a Downturn,” Foreign Policy, February 26, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/02/26/china-starts-the-lunar-new-year-with-an-economic-hangover/; and William Pesek, “China’s Deflation Could Go Global, Fast,” Barron’s, March 13, 2024, https://www.barrons.com/articles/china-deflation-global-economy-trade-war-3029367e.

2 “Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) for National Economic and Social Development and Vision 2035 of the People’s Republic of China,” The People’s Government of Fujian Province, August 9, 2021, https://www.fujian.gov.cn/english/news/202108/t20210809_5665713.htm.

3 “World Economic Outlook—Steady but Slow: Resilience Amid Divergence,” International Monetary Fund, April 2024, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2024/04/16/world-economic-outlook-april-2024.

4 China's General Administration of Customs of the People's Republic of China. Accessed March 9, 2024

5 Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC). Accessed, January 14, 2024

6 Zainab Usman and Alexander Csanadi, “How Can African Countries Participate in U.S. Clean Energy Supply Chains?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 2, 2023, 16, https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/10/02/how-can-african-countries-participate-in-u.s.-clean-energy-supply-chains-pub-90673.

7 Ibid.

8 “Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Dakar Action Plan (2022–2024),” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China,” November 30, 2021, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/2649_665393/202112/t20211202_10461183.html.

9 Che Bin, Huang Weixin, and Huang Peizhao,“Kenyan Avocado Finds Ready Market in China After CIIE Debut,” People’s Daily, November 5, 2023, http://en.people.cn/n3/2023/1105/c90000-20093140.html.

10 World Bank. "Distribution of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Sub-Saharan Africa from 2010 to 2022, by sector." Chart. October 26, 2023. Statista. Accessed May 18, 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1322302/share-of-economic-sectors-in-gdp-in-sub-saharan-africa/ and World Bank. "Contribution of agriculture, forestry, and fishing sector to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Africa as of 2022, by country." Chart. October 26, 2023. Statista. Accessed May 18, 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1265139/agriculture-as-a-share-of-gdp-in-africa-by-country/

11 “Cross-Border E-commerce Brings New Opportunities to China-Africa Economic and Trade Co-op,” Belt and Road Portal, April 13, 2023, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/313953.html; and Carlos Mureithi, “African Diplomats Are Live-Streaming and Making Deliveries to China’s Consumers,” Quartz, January 27, 2022, https://qz.com/africa/2117788/african-nations-bet-big-on-chinas-e-commerce-market.

12 Ibid.

13 Carien du Plessis and Tannur Anders, “China Says African Countries Want Industrialisation Over Infrastructure,” Reuters, August 22, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/china-says-african-countries-want-industrialisation-over-infrastructure-2023-08-22/.

14 Jon Emont, “The Era of Ultracheap Stuff Is Under Threat,” Wall Street Journal, August 7, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/asia-factories-consumer-goods-labor-prices-7140ab98.

15 Fiona Robertson, “Urgent Solutions for a New Era of Debt Distress,” One, September 6, 2022 (updated January 11, 2024), https://data.one.org/data-dives/debt/.

16 Matthew Mingey and Logan Wright, “China’s External Debt Renegotiations After Zambia,” Rhodium Group, June 29, 2023, https://rhg.com/research/chinas-external-debt-renegotiations-after-zambia/.

17 Sebastian Horn, Bradley Parks, Carmen M. Reinhart, and Christoph Trebesch, “China as an International Lender of Last Resort,” Working Paper no. 31105, National Bureau of Economic Research, April 2023, https://www.nber.org/papers/w31105.

18 “African Currencies are Under Pressure Amid Higher-for-Longer U.S. Interest Rates” https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/05/15/african-currencies-are-under-pressure-amid-higher-for-longer-us-interest-rates and “Managing Exchange Rate Pressures in Sub-Saharan Africa—Adapting to New Realities,” in Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa—The Big Funding Squeeze, International Monetary Fund, April 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/SSA/Issues/2023/04/14/regional-economic-outlook-for-sub-saharan-africa-april-2023.

19 Barry Eichengreen, Camille Macaire, Arnaud Mehl, Eric Monnet, and Alain Naef, “Is Capital Account Convertibility Required for the Renminbi to Acquire Reserve Currency Status?,” Banque de France Working Paper no. 892, November 2022, https://publications.banque-france.fr/sites/default/files/medias/documents/wp892.pdf.

20 Gerard Di Pippo and Andrea Leonard Palazzi, “It’s All About Networking: The Limits of Renminbi Internationalization,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 18, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/its-all-about-networking-limits-renminbi-internationalization.

21 Pan-African Payment and Settlement System, https://papss.com/about-us/; and Zainab Usman and Alexander Csanadi, “Latest Milestone for the African Continental Free Trade Area: The Pan-African Payment and Settlement System,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 7, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/02/07/latest-milestone-for-african-continental-free-trade-area-pan-african-payment-and-settlement-system-pub-86376.

22 Use of these third-party currencies generates not only significant time lags, but also substantial costs from the conversion process amounting to as much as $5 billion annually. William Ukpe, “PAPSS Will Boost Intra-Africa Trade and Save Africa $5 Billion—Mene, AfCFTA Secretary—General,” Nairametrics, no date (published two years ago), https://nairametrics.com/2022/01/14/afcfta-pan-african-payment-settlement-system-launches-to-save-africa-5-billion/.

23 Noriyuki Doi and Saki Akita, “Yuan Exceeds Dollar in China’s Bilateral Trade for First Time,” Nikkei Asia, July 25, 2023, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Markets/Currencies/Yuan-exceeds-dollar-in-China-s-bilateral-trade-for-first-time.

24 Andrew Mullen, “Explainer: Which 8 Countries Are Using China’s Yuan More, and What Does It Mean for the US Dollar?,” South China Morning Post, May 10, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/economy/economic-indicators/article/3220087/which-8-countries-are-using-chinas-yuan-more-and-what-does-it-mean-us-dollar.

25 Eichengreen, “Is Capital Account Convertibility Required for the Renminbi to Acquire Reserve Currency Status?”

26 Kaixuan Hao, Liyan Han, and (Tony) Wei Li, “The Impact of China’s Currency Swap Lines on Bilateral Trade,” International Review of Economics and Finance 81 (2022): 173–83, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1059056022001356#:~:text=Currency%20swaps%20can%20enhance%20the,effect%20and%20an%20amplifying%20effect.

27 China's General Administration of Customs of the People's Republic of China. Accessed March 9, 2024; Hope Moses-Ashike, “Nigeria-China Currency Swap Fails to Stabilise Naira 5 Years After,” Business Day, April 12, 2023, https://businessday.ng/business-economy/article/nigeria-china-currency-swap-fails-to-stabilise-naira-5-years-after/.

28 Bakare Majeed, “Reps Move to Revive Yuan/Naira Swap Deal,” Premium Times, December 20, 2023, https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/more-news/653038-reps-move-to-revive-yuan-naira-swap-deal.html.

29 Michael Stott, “BRICS Bank Strives to Reduce Reliance on the Dollar,” Financial Times, August 22, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/1c5c6890-3698-4f5d-8290-91441573338a.

30 “Why African Students Are Choosing China,” U.S. News and World Report, June 29, 2017, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2017-06-29/china-second-most-popular-country-for-african-students.

31 “White Paper: China and Africa in the New Era: The State Council Information Office of the PRC,” China Daily, November 26, 2021, https://language.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202111/26/WS61a07e75a310cdd39bc77c4d_2.html.

32 “Xi Jinping and Ramaphosa co-chair China-Africa leaders’ dialogue” (习近平和南非总统拉马福萨共同主持中非领导人对话会), Ministry of Foreign affairs, August 25, 2023. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/zyxw/202308/t20230825_11132507.shtml

33 Changsong Niu, Si’ao Liao, and Yi Sun, “African Students’ Satisfaction in China: From the Perspectives of China-Africa Educational Cooperation,” Journal of Studies in International Education 27, no. 2 (2023): 298–315, https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153211052771.

34 “White Paper: China and Africa in the New Era” The State Council Information Office of the PRC, November 2021, http://english.scio.gov.cn/whitepapers/2021-11/26/content_77894768.htm.

35 Sun Xiaomeng and Zhu Wenshan, “China-Africa people-to-people exchange status and prospect after ten years of ‘Belt and Road’” (“一带一路”十年 中非人文交流现状与展望) Shenzhou Xueren (神州学人)No. 11, 2023, https://mp.pdnews.cn/Pc/ArtInfoApi/article?id=38686609.

36 ““游非洲”正在升温——中非旅游合作不断拓展”, Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, May 8, 2024, http://www.focac.org.cn/zfgx/rwjl/202405/t20240508_11301343.htm.

37 The African Climate Foundation and the London School of Economics, “Implications for African Countries of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism in the EU” 2023 https://www.lse.ac.uk/africa/assets/Documents/AFC-and-LSE-Report-Implications-for-Africa-of-a-CBAM-in-the-EU.pdf

38 Corentin Cohen, “Will France’s Africa Policy Hold Up?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 2, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/06/02/will-france-s-africa-policy-hold-up-pub-87228.

39 British High Commission Nairobi, “UK and Kenya hold First-ever Economic Partnership Agreement Council to Secure Jobs and Increase Trade” March 21, 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-and-kenya-hold-first-ever-economic-partnership-agreement-council-to-secure-jobs-and-increase-trade

.jpg)