What can a formal cost-benefit analysis, a standard tool in military planning and corporate strategy, tell us about the utility of Ukraine’s ongoing strike campaign against Russia’s oil refining sector and other military and critical infrastructure targets? Several months since the first attack, there is enough data to analyze the true extent of the damage.

Since 2014, Ukraine has waged war more like a tech start-up than an old-fashioned corporate conglomerate: through crowdsourcing, multiple competing groups, and trying and testing various approaches with a “let a thousand flowers bloom, move fast, break things” philosophy. Various operations are planned and executed independently by different parts of the Ukrainian military. Successful operations are likely rewarded and their authors and implementers given resources for future endeavors. This approach delivers quick evolution, but it also skews the choice of attack targets toward their PR value.

A Convenient Target

Oil is seen as the mainstay of the Russian economy, so elements of the oil industry are obvious and symbolic targets. Unlike oil fields, which are vast with dispersed islands of equipment and located in remote Siberia, refineries appear to be a far more rewarding target. Refineries cost tens of billions of dollars to build; they are large targets and therefore hard to miss; and there is a lot of flammable and explosive matter, making substantial fire damage probable after the hit. There are also plenty of Russian refineries relatively close to Ukrainian territory.

From the attack planners’ standpoint, it would be ideal if Russia were not only to lose export volumes, but also experience difficulties in supplying enough fuel for its army and economy. Alas, that would require a very large-scale attack, as Russian refining capacity is 2.5 times bigger than its fuel consumption.

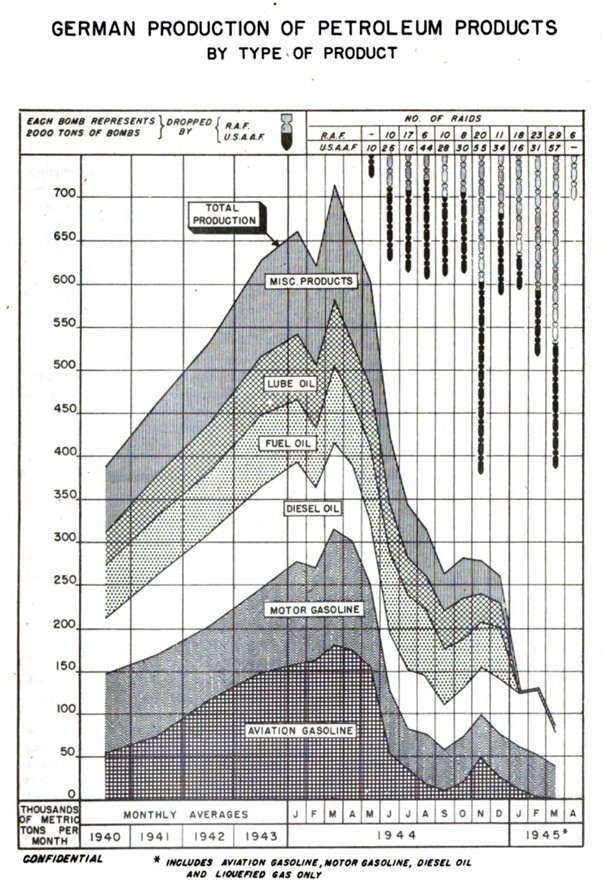

This logic is not new. Eighty years ago, U.S. and British military planners had a similar idea: to bring Germany and its army to its knees by targeting oil refineries in Germany, Austria, and Romania. For a year from May 1944, over 200,000 tons of bombs were dropped in more than 600 raids, with about 2.5 percent landing on refinery installations. Even under that scale of attack, after the initial shock, German fuel production stabilized at about 40 percent of its previous level.

Oil Division Final Report, US Strategic Bombing Survey (January, 1947). Source:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015011672485&seq=1

Modern UAVs are far more precise than World War II bombers, but their payload is also quite small: from 5 to 50 kilograms of explosives, compared with 500-kilogram bombs. A small charge can only damage but not destroy an installation directly hit by the drone, and does not cause any damage to neighboring installations.

This disadvantage could be compensated for by increasing the size of the attacking drone swarms and the frequency of the attacks, but it is unclear whether Ukraine has enough resources to do that.

What is clear is that Ukrainian planners tried to maximize the number of damaged refineries and the geographical reach of the attacks, rather than the amount of damage caused to every impacted plant. The PR value of the campaign might play a role in this choice.

In terms of the direct monetary cost, each attack likely cost $1–5 million per raid and site—a relatively small price for an attack on a multibillion dollar target.

The Cost for Russia

The expectations of the benefits for Ukraine (or the costs to its adversary) were probably vast, starting with an intangible one: demonstrating that Ukraine could target valuable industrial installations more than 1,000 miles from its territory boosted Ukrainian morale and damaged Russia’s. There was also an expectation of direct economic damage: the cost of repairs, lost revenue, and cascade damage to the fighting capacity, economy, and population’s well-being from a shortage of fuels. It is impossible to know what figures featured in the Ukrainian military planners’ calculations. Many observers assumed that the imposed costs on Russia would be quite high: at least billions, and more likely tens of billions of dollars.

Russia has been steadily reducing the publicly available amount of data on its oil industry, making analysis of the attacks’ outcomes more difficult. Russian oil companies have not published much information on what exactly has been hit and how seriously. Any estimates are based on press reports and social media posts. Initial coverage reported that almost every targeted refinery had sustained some damage to some of its primary distillation units.

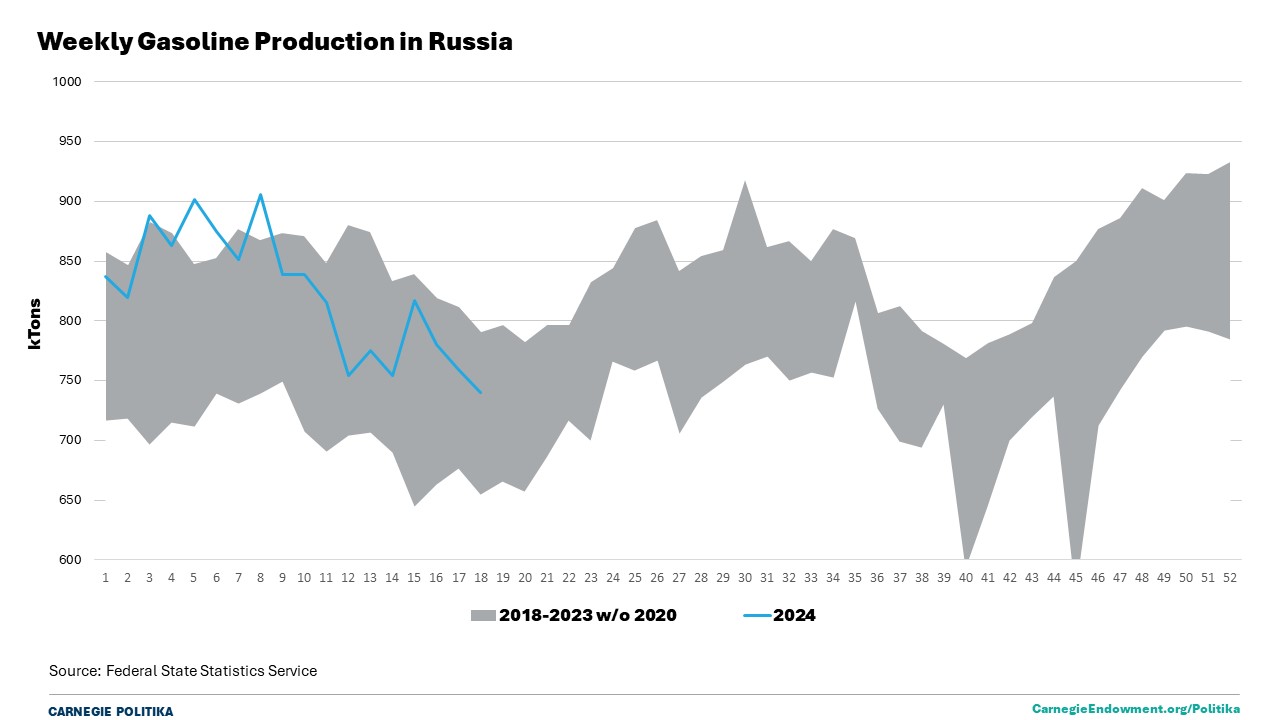

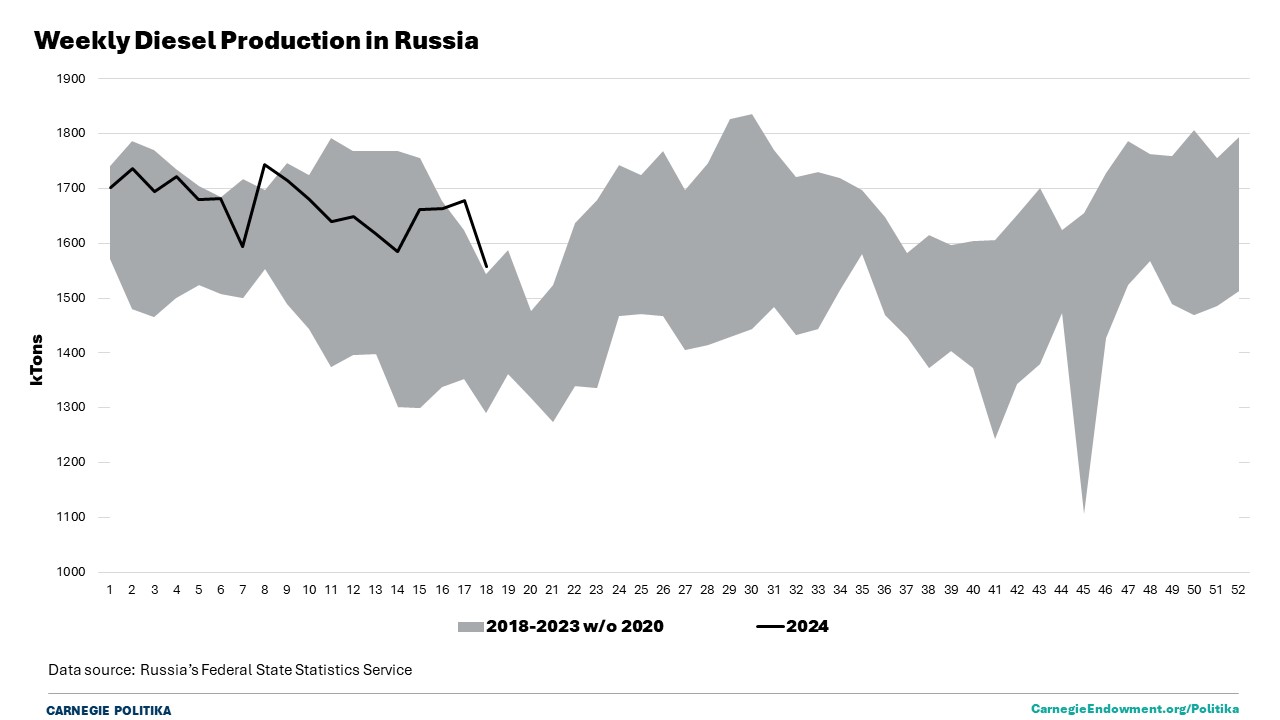

Nevertheless, until late May 2024, Rosstat, the state statistics agency, published weekly reports on gasoline and diesel production volumes, and still publishes the retail prices of fuels. Other sources of available data include trading volumes and prices at Russia’s main commodity exchange and export loadings and shipping data collected by Kpler and other agencies, based on ships’ movements.

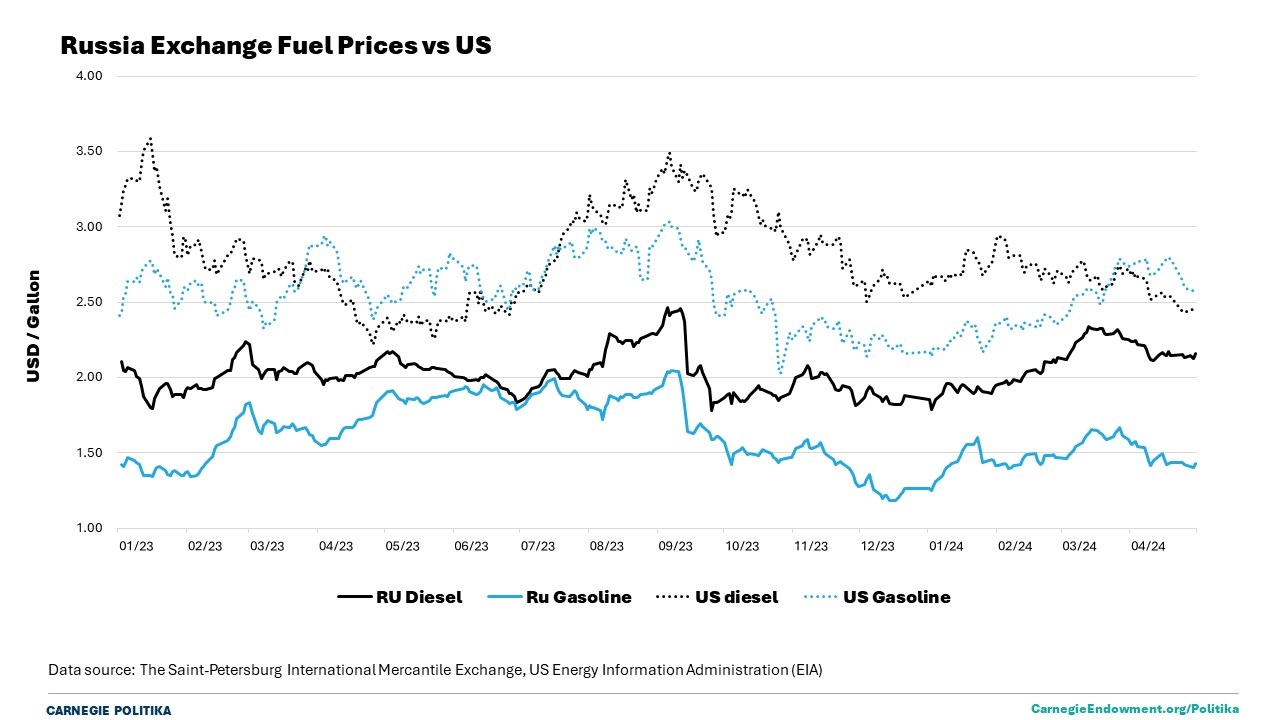

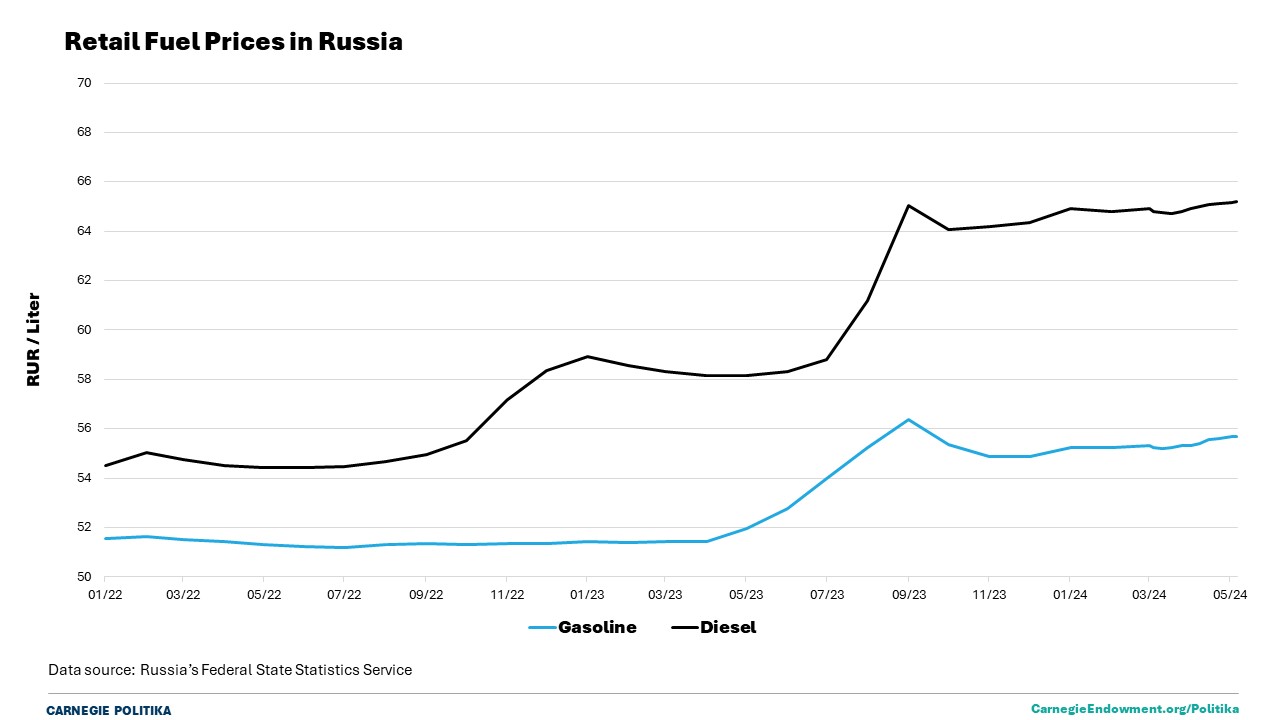

The data show that Russian domestic fuel retail prices were extremely stable. Domestic wholesale prices showed some movement, but that movement could be explained by fluctuations on the international markets, and was less drastic than price movements on the U.S. wholesale oil product markets. Diesel and gasoline production has declined from the beginning of March, but declines of such amplitude and duration have been observed before, and even at the nadir of the decline, production stayed well above historical levels since 2018 (excluding the COVID-hit year of 2020, when production was uncharacteristically low and therefore unsuitable for comparison). Even export shipments did not show any pronounced and definitive pattern assignable to the attacks.

News reports show that damaged units at many of the refineries were back in operation after two to three weeks of repairs, and Bloomberg-reported refining volumes are down from their peaks but above the troughs and again within the customary volume band.

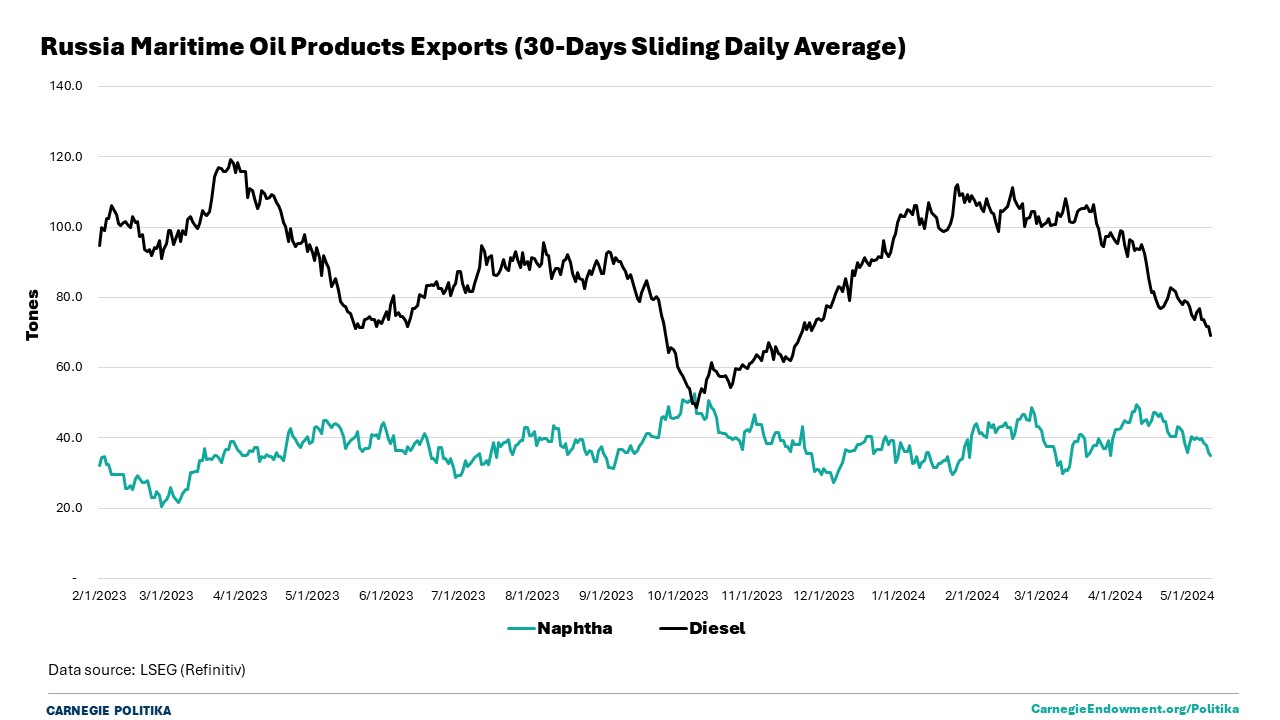

Russia did import some volumes of gasoline from Belarus, which was widely celebrated by the media. But the volume in question was a single trainload in one week—less than 0.5 percent of one week’s consumption—while Russia kept exporting naphtha (straight-run gasoline) and diesel. Considering that not a single unit converting naphtha into gasoline was subject to an attack, that import was most likely for logistical reasons, rather than because of a countrywide shortage of fuels.

No Impact on Exports

All this evidence suggests that the true losses Russia has incurred from the wave of attacks on refineries is the cost of repairs—probably in the vicinity of tens of millions of dollars per plant: a large sum compared to the costs of the attacks, but very far from the initial hopes and estimates of billions—and some lost revenue from the volumes that had to be exported as crude oil instead of oil products. For the oil companies, the loss could be up to $15 per barrel on the switched volumes. According to Bloomberg, Russia refined 5.2 million barrels of oil per day on average in April 2024, compared to 5.5 million in January. Assuming that all of the 300,000 barrels per day that were not accepted into refineries were exported as crude oil rather than a product basket, this switch would lead to a loss of $135 million for the month of April. According to CREA data, Russia earned more than $16 billion from its oil and oil products exports during the same period.

The Russian government is to a large extent indifferent as to whether Russian oil companies sell their volumes as crude or oil products. It taxes crude oil at the wellhead quite heavily, using a formula linked to global prices, and then taxes corporate profits. Corporate profits go up when oil companies export products instead of crude, but the effect on the state budget is rather small. Coincidentally, the Russian government pays a subsidy of $10 per barrel on refined volumes, so it might actually benefit from the switch.

In the event of a truly successful attack on Russian refining, a large percentage of the global refining capacity would be taken out of operation, and if that happens, the shortage of manufacturing capacity would drive the price of crude oil down, but substantially widen the refining spread (the price difference between crude oil and fuels made out of it), causing gas station prices to go up. This was apparently the concern of the U.S. administration voiced by Vice President Kamala Harris to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in Munich in February 2024.

Oil and fuel prices did not go up as a result of the attacks. Yet this was most likely not because U.S. officials’ reasoning was flawed, but because the effect of the attacks was not big enough: in 2023, Russia exported 700,000 barrels of diesel per day, but the difference between the highest and lowest weekly average production in 2024 was about 150,000 barrels per day and the trough did not last long.

Switching might force Russia to look for additional buyers for its crude oil, which could cause difficulties for a country under sanctions and selling its crude to a handful of buyers, but the switched volumes are similar to the production cut under the OPEC+ deal, so it should not be much of a problem. So far, therefore, the attacks on the refineries have imposed some costs on Russia, but have not had any drastic game-changing effects.

During the first wave of the attacks, their limited extent was quite clear. Ukraine managed to increase the intensity and scale of the attacks in March, but not enough to make a substantial difference. In later months, Kyiv focused on more distant targets, increasing both the share of Russian refining under threat and the potential scope of the attacks, but after four months, the campaign has failed to reach critical mass and gravity.

The Fallout for Ukraine

Was there any cost to Ukraine beyond the direct cost of the drones used in the attacks?

Perhaps there was. The Russia-Ukraine war may look like a total war in which each side is trying to destroy everything within its reach and means, but the reality is more complex. The Kremlin appears to be fighting a compartmentalized war, leaving certain areas of Ukrainian life and economics relatively untouched—until it decides that Ukraine has provoked it to a retaliatory hit. Sometimes it pulls back, like when it stopped attacking Ukraine’s grain export infrastructure. Possibly the Kremlin’s conflict management strategy is to maintain some unused space on the escalation ladder.

The obvious target for retaliatory strikes on refineries would be the Ukrainian refining sector, but it was already weak before the beginning of the war, and the only refinery that was running when the war started—Kremenchug—was attacked soon after the war began and then again in February 2024, shortly after the first drone attacks on Russian refining. That was clearly not enough for the Russians looking for revenge, so they turned their sights—not for the first time—to Ukraine’s electrical power infrastructure.

The Kremlin attacked elements of Ukrainian power infrastructure in the winter of 2022–2023 with limited success, but then the attacks stopped. Back then, the attacks employed the light cavalry of cheaper and less numerous drones and targeted easy-to-hit transformers. The damage was fixed relatively quickly.

In the spring of 2024, the Kremlin methodically attacked Ukrainian power generation capacity, aiming for turbines, generators, and control equipment with massive combined attacks that were quite effective, targeting both thermal and hydroelectric power. There was a devastating hit on the generation units of DniproGES, the largest Ukrainian hydro station, and the Kremlin keeps destroying thermal power stations with frequency regulation capacity. If enough of them are destroyed, the power system will become very difficult to run. It will be expensive to fix the power stations, and in some cases, the owner DTEK has said it does not know exactly how it will do it: the equipment was from the Soviet era and the spare parts have not been manufactured in decades, so the whole control system may have to be replaced.

It is possible that Russia would have attacked the power stations now regardless of the attacks on refineries—or later for any other imagined reason, however spurious—so perhaps this cost would have been incurred eventually in any case. On the other hand, it might have been avoided in the here and now.

Russia has also started to hit Ukraine’s gas infrastructure, beginning from the injection site of the largest underground gas storage facility in Ukraine that it had offered to European gas traders. This was the first attack on this type of target: until recently, Russia had abstained from attacks on gas infrastructure, probably as a quid pro quo for unhindered gas transit to Europe.

Lessons Learned

Putin’s bullying and deterrence tactics will not stop Ukrainian military operations—if and when those operations yield results that outweigh the costs incurred, both direct and indirect. The strategic start-up approach focuses on doing first and analyzing later rather than paralysis by analysis. But it also depends on lessons learned.

The bulk of the current analysis of the attacks on refineries is celebratory, with a strong element of confirmation bias—and that is a classical folly that prevents learning. Russia’s refining sector, unlike its Black Sea Fleet, has proven to be resilient to the recent type of attacks, rather than the Achilles’ heel of the Russian economy that many were hoping it would be. That might have been hard to establish before the attacks, but is worth noting now as the result of careful and dispassionate analysis of the aftermath. That analysis may still leave Russian refineries on the list of attack-worthy targets, but as a calculated decision based on facts and full sets of figures rather than emotions and cherry-picked data.

An abridged version of this commentary was initially published in Foreign Affairs in response to an article by Michael Liebreich, Lauri Myllyvirta, and Sam Winter-Levy.