Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Chinese exports to Russia have risen by more than 60 percent. Many analysts suggest that trade with China is providing nothing short of a lifeline to Russia’s economy. In the process, China has emerged as the largest supplier of not only commercial goods, but increasingly of dual-use components covered by Western export controls.

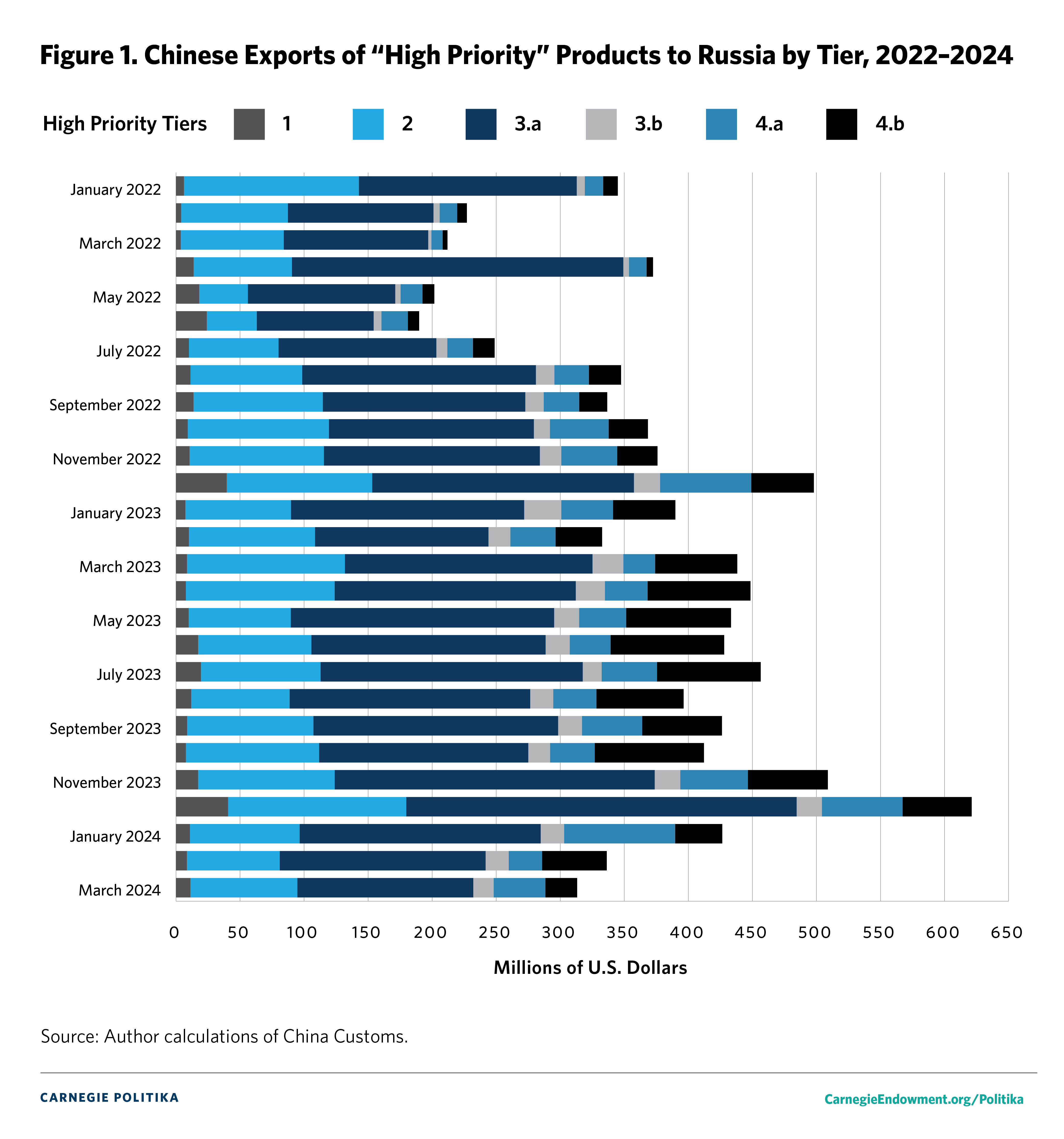

Publicly available customs data indicate that every month, China is exporting over $300 million worth of dual-use products identified by the United States, the European Union, Japan, and the United Kingdom as “high priority” items necessary for Russia’s weapons production (Figure 1). While monthly transactions have declined from a peak of over $600 million in December 2023, China remains Russia’s largest supplier of these controlled products.

High priority items refer to fifty dual-use products that are essential for manufacturing weaponry like missiles, drones, and tanks. Many are products that Russia lacks the capacity to produce domestically such as microelectronics, machine tools, telecommunications gear, radars, optical devices, sensors, and other products. The majority of the goods on the high priority list overlap with the items that U.S. officials in early April revealed China was selling to Russia.

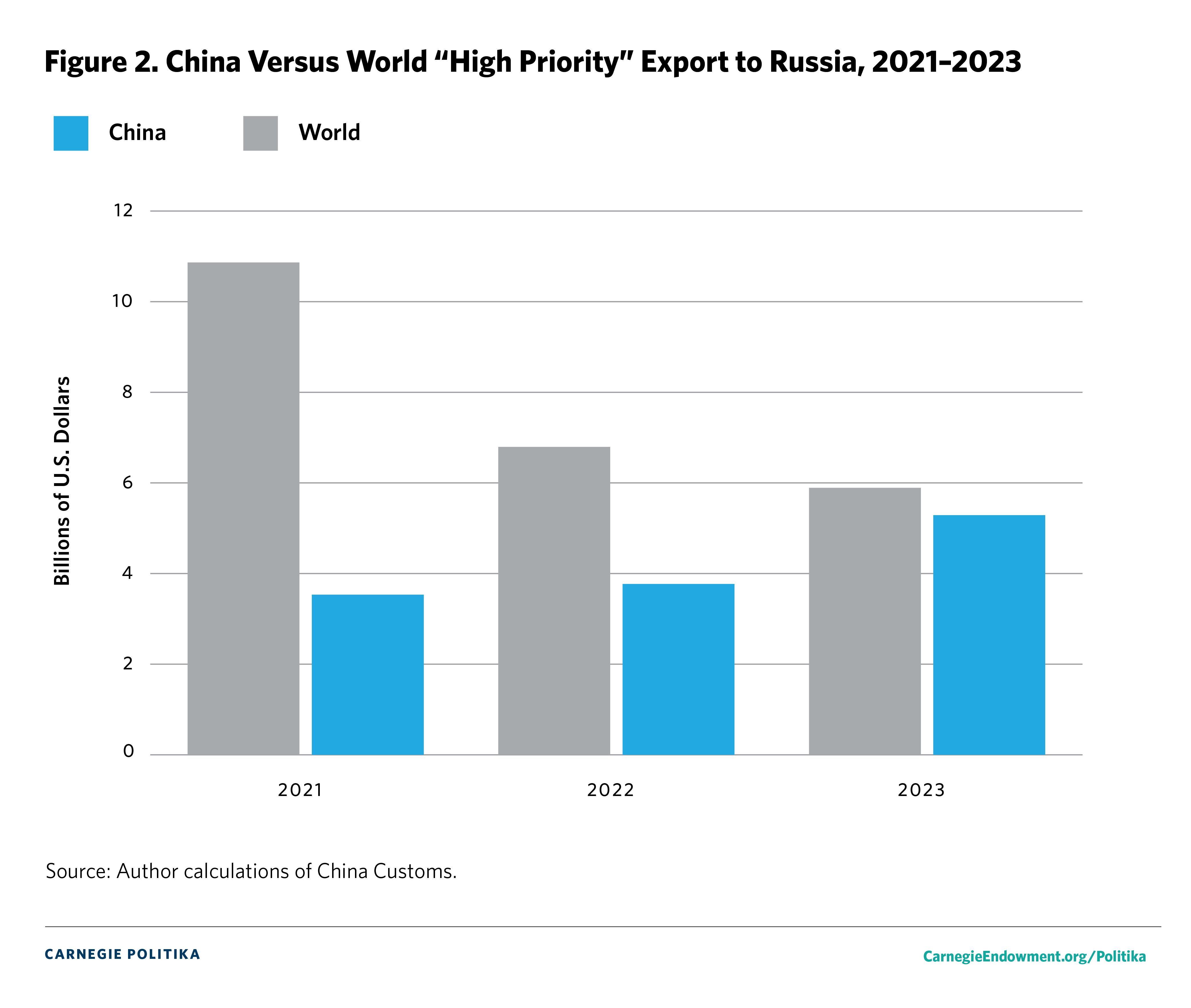

Despite the sensitivity around dual-use trade with Russia, China’s General Customs Administration continues to report bilateral transactions, even in areas subject to the Western export controls. In 2023, China was responsible for approximately 90 percent of Russia’s imports of goods covered under the G7’s high priority export control list (Figure 2).

Whether or not Russia can sustain its invasion of Ukraine hinges substantially on its ability to acquire inputs to power its war machine. Since early 2022, Russia has lost over 10,000 units of key equipment, including tanks, armored vehicles, artillery systems, and drones. Although Russia has managed to ramp up production of artillery, its ability to produce specialized products like microelectronics and optical devices remains insufficient. Russia’s chipmaking capabilities, in particular, are limited to decades-old 65-nanometer technology. Consequently, Chinese exports have played a key role in sustaining Moscow’s war effort. Russia’s reliance on China for high priority products surged from 32 percent in 2021 to 89 percent in 2023.

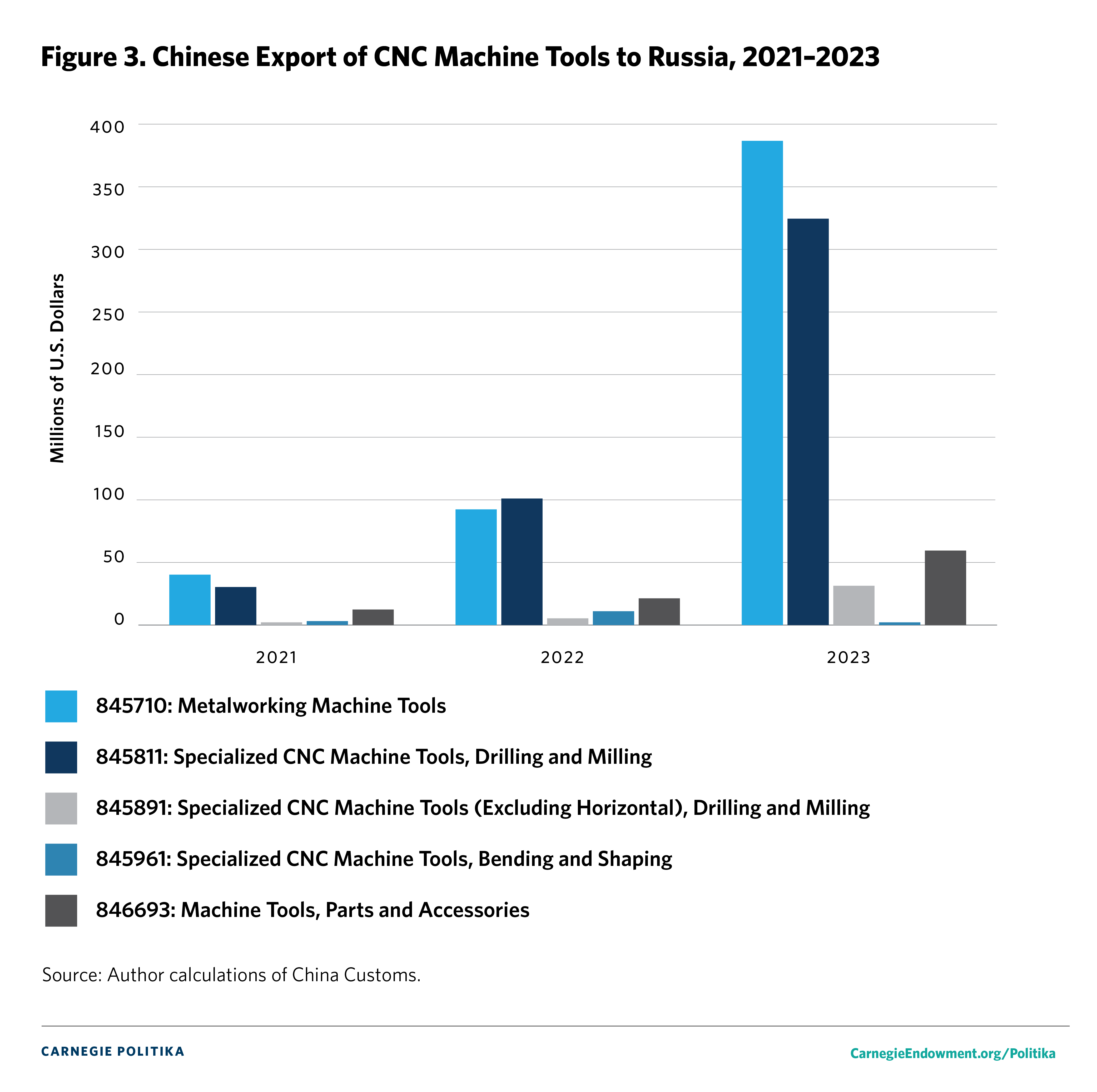

Semiconductors, telecommunications equipment, and machine tools were among the largest categories of Chinese exports to Russia covered under the high priority export control list in 2023. Machine tools alone accounted for nearly 40 percent of the year-on-year rise in Chinese dual-use exports (Figure 3).

Despite backfilling by Beijing, export controls have otherwise succeeded in degrading Russia’s ability to acquire dual-use components. According to trade figures reported by Russia’s bilateral trade partners, the country’s overall imports of high priority items has dropped by 45 percent since the war in Ukraine began. That said, Russia has been able to gain access to some microelectronics by buying and then disassembling ordinary consumer products not covered under the Western export controls.

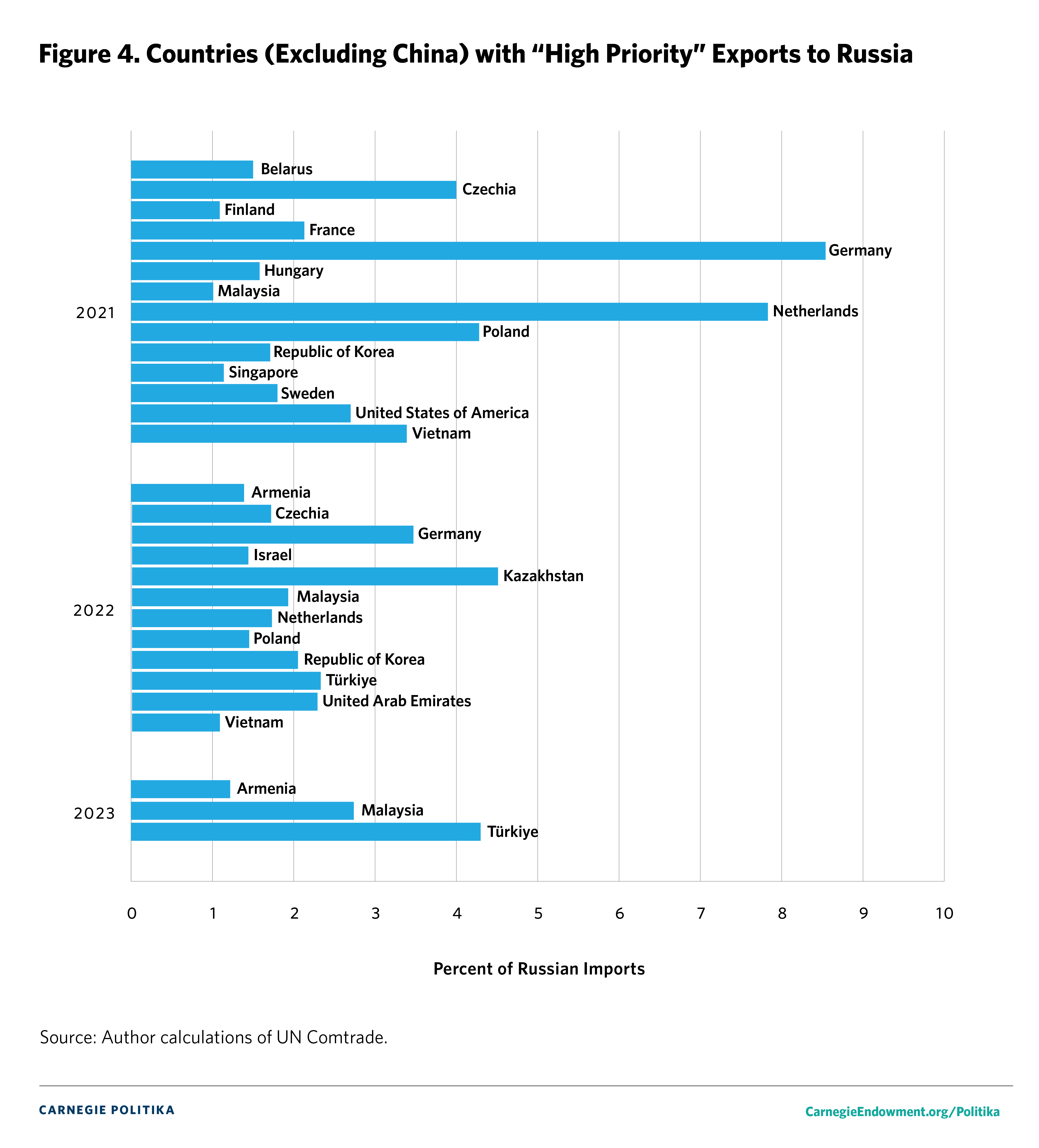

Other than China, the number of countries willing to export dual-use goods to Russia has declined since 2021. Last year, Turkey, Malaysia, and Armenia were the only countries beyond China willing to provide more than one percent of Russia’s total high priority imports, representing 4.3 percent, 2.7 percent, and 1.2 percent, respectively (Figure 4). These figures cast doubt on the notion that China is circumventing export controls via transshipment.

Instead, Chinese exporters are openly engaging in trade with Russia, even in areas subject to export controls, while few other countries have been willing to report trade data in circumvention of the Western restrictions. That said, third party financial intermediaries have begun to play a significant role in facilitating China-Russia payments, indicating Beijing’s potential sensitivity to the risk of secondary sanctions on financial institutions as compared with goods exporters.

One important question is whether the Chinese government is directly involved in such transactions with Russia or whether private firms have been largely responsible for evading sanctions and export controls. While this distinction matters little in terms of the ultimate effect on Russia’s defense base, it could affect how U.S. policymakers respond to strengthening China-Russia defense ties.

Previously, Washington maintained that Beijing was not providing lethal aid to Moscow on a “systematic” basis. When meeting with Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng in November 2023, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stated that private companies, not Chinese officials, were responsible for sanctions evasion.

Since then, however, Beijing has done little to prevent such transactions, given the rise in dual-use trade with Russia. In fact, U.S. officials have begun to suggest that Beijing is now actively encouraging these transactions. Departing from prior assessments, U.S. officials recently said that China was “taking a systematic effort to support Russia’s war effort.”

Increasingly deep links between the Chinese party-state and private firms make it difficult to imagine a scenario in which Beijing would not have foreknowledge of dual-use transactions with Russia, especially in highly sensitive domains. The fact that China’s General Customs Administration willingly reports trade figures with Russia indicates Beijing’s lack of regard for the Western export control regime: something Chinese officials have often criticized as “long-arm jurisdiction” by the United States.

U.S. officials have warned repeatedly in recent weeks that Chinese entities found to be conducting or facilitating transactions in support of Russia’s defense industry will face blocking sanctions. Washington has already added over one hundred Chinese entities to the Treasury Department’s Specially Designated Nationals list and the Commerce Department’s Entity List since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Given China’s continued support for the Russian military, more and more Chinese exporters and financial intermediaries will likely face secondary sanctions and export controls going forward.

Beyond the threat of punitive measures, the United States has limited ability to influence Beijing’s calculus on the Russia-Ukraine war. From Beijing’s perspective, the war has helped divert Western resources and attention away from the Indo-Pacific. Chinese officials perceive the United States as being bent on strategic competition with China, and as a result, see little upside in heeding U.S. demands and foreclosing support for Russia.

While China may not want to upend ties with Europe and the United States, it seeks to ensure that Russia remains a stable strategic partner. Providing Russia with dual-use components rather than finished weapons has allowed China to provide support for Russia while claiming plausible deniability. Even if Beijing curtails dual-use exports in order to avoid further sanctions, its strategic interest in Russia remaining a stable partner will persist.