In recent years, some Gulf countries have joined the BRICS+ group of nations and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), signaling the evolving nature of Chinese and Russian influence in the region through multilateral organizations. Yet it is primarily through bilateral engagements that Chinese and Russian actors exercise influence and exert power in the region. Areas such as energy cooperation, trade and investment, finance, and tourism are highly visible and largely uncontroversial spheres of engagement for China and Russia. But their collaboration with Gulf countries in the military, technology, and other noneconomic domains have unsettled many American and European officials.

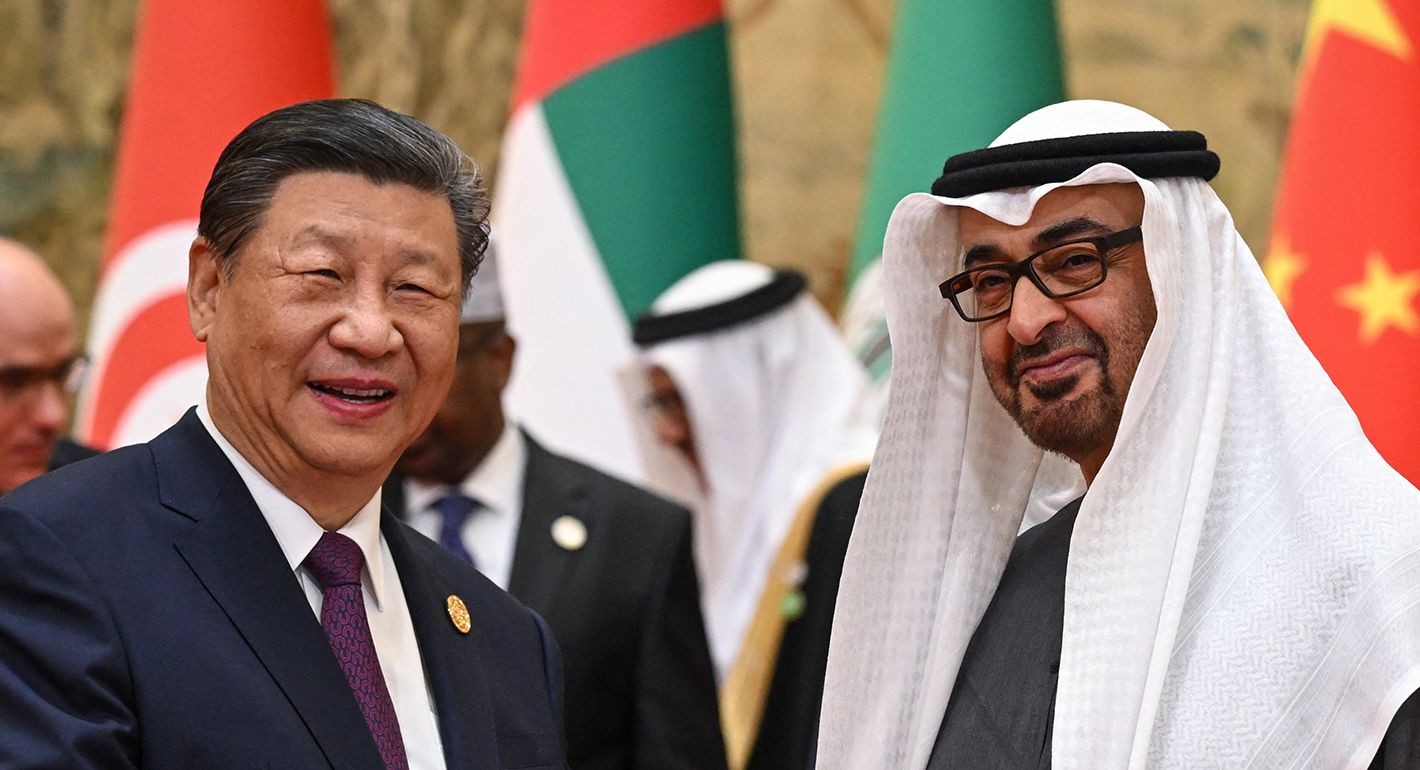

In the latter half of the twentieth century, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region was a sphere of rivalry between China and the Soviet Union. Today, Beijing and Moscow seek to project cautious alignment in their regional roles through joint military drills and policy stances toward crises and conflicts. Chinese President Xi Jinping told Russian President Vladimir Putin in March 2023 that “right now there are changes—the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years—and we are the ones driving these changes together.” Indeed, the Israel-Hamas war that began in October 2023 and the subsequent related Yemeni Houthi rebels’ attacks on commercial ships in the Red Sea presented the Chinese and Russian governments with various opportunities to showcase their leadership and amplify the perceived strategic foreign policy failures of the United States throughout the broader region.

An exploration of the key dimensions and interplay of Chinese and Russian interests and influence in Gulf countries, namely the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, Iran, and Iraq, reveals whether and where China and Russia regional engagement actually results in strategic collaboration or competition. Three main manifestations of Chinese and Russian engagement in the region involve economics, multilateral groupings, and conflict diplomacy. The countries’ intersecting interests and influence in these domains, combined with their uneven levels of engagement across the region, have created a complex geopolitical arena wherein these two powers must navigate conflicting and overlapping interests.

Levels of Interest and Influence

MENA-focused scholars are often keen to proclaim the strategic significance of the region to every global power in the world. However, MENA does not represent a core strategic region for either Beijing or Moscow. It is more accurate to view the region—and, by extension, the Gulf subregion—as being third or fourth in order of significance for Chinese and Russian government officials. Domestic stability, frontiers, and relations with neighboring countries consume the immediate attention of policymakers in China and Russia. China’s economic challenges and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlight the strategic interests attached to developments unfolding closer to home than those in Gulf countries.

However, this reality does not necessarily mean that Chinese and Russian engagement in the Gulf lacks important regional implications. A close look at the relatively stable, wealthy GCC countries, as well as Iraq and Iran, indicates that Chinese and Russian influence is deep and multifaceted. It also illustrates that both Chinese and Russian influence is uneven within each Gulf country and between the economic and noneconomic domains; moreover, the two powers’ footprints are different and uneven across the region. Below, their various levels of engagement are discussed in three key areas: economics, multilateral groupings, and conflict diplomacy.

Economic Engagement

The economic domain is a logical starting point for assessing Chinese and Russian engagement with Gulf countries. Energy considerations occupy a priority position on China and Russia’s economic agendas, especially as broader trade and investment flows reveal a strong energy dimension. As the world’s largest importer of crude oil, China relies heavily on Gulf countries to meet its energy needs, which increased by 10 percent up to 11.3 million barrels per day of crude oil from 2022 to 2023. Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran (though many Iranian imports are assumed to be relabeled), the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Oman served as top sources of China’s crude oil imports in 2023. Meanwhile, Qatar secured multiple long-term liquified natural gas (LNG) supply deals with Chinese customers between 2021 and 2023.

Chinese energy customers rely on a steady supply of affordable commodities imported from Gulf countries. But despite this heavy reliance, Beijing’s approach to energy security involves a variety of global energy partners and a flexible energy mix. China aims to ensure a balanced portfolio of imports, and it is rare that a single country supplies more than 10–15 percent of total imports for a given energy commodity. However, these thresholds can sometimes shift for opportunistic reasons, such as the availability of discounted Russian crude oil after the invasion of Ukraine. China can likewise draw upon various energy forms—coal, crude oil, natural gas, hydrogen, and nuclear—to manage supply disruptions.

Chinese-Gulf energy partnerships are a two-way economic street. In 2022, Saudi Aramco made a final investment decision to develop a multibillion-dollar refinery and petrochemical complex in northeast China after an initial agreement on project plans emerged in 2019. Qatar Energy signed a $6 billion agreement with China State Shipbuilding Corporation in April 2024 to build eighteen LNG carriers, following a similar deal in 2021 worth $762 million.

Russia’s position in the energy supply-demand equation is distinct from that of China’s with the Gulf countries. Russia simultaneously competes with some Gulf producers insomuch as it represents a major energy supplier to China and collaborates with major Gulf producers to manage global oil prices. For example, Russia served as China’s largest supplier of crude oil in 2023 (at 19 percent of Chinese crude oil imports). Meanwhile, Russian energy officials continue to work alongside Gulf counterparts on oil supply policy within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and allies led by Russia, known as OPEC+ (though disagreements have led to previous breakdowns in the alliance). In April 2024, OPEC+ members extended voluntary oil supply cuts through June 2024 in a bid to keep the global market tight and prices elevated. The group subsequently agreed to extend production curbs into 2025, though the agreement included considerable room for adjustments.

The influence of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the Gulf, both in terms of annual inflows and stocks, far outweighs that of Russia. Saudi Arabia is a major hub for foreign investment in the region and serves as a good case to illustrate the marked difference between China’s and Russia’s investment trends. According to Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Investment, annual Chinese inward FDI flows ranged from $135.7 million to $1.2 billion during the period 2020–2022, while Russian inward FDI remained essentially nonexistent during this period. In 2019, Russian FDI inflow figures registered disinvestments amounting to $20.3 million, whereas Chinese FDI inflow in that year reached $719.2 million. FDI stocks reveal a similar story: cumulative FDI from China stood at $5.4 billion in 2022, while that of Russia registered a mere $27.5 million. It is worthwhile mentioning that FDI from the United States, in terms of annual inflows and total stocks, far exceeded that of both China and Russia during the period 2019–2022.

Chinese firms—and to a lesser degree Russian ones—see attractive investment opportunities in various sectors across the Gulf, including renewables, construction, electric vehicles, and technology. However, U.S. influence in the region has impacted economic collaboration, especially in the technology sector. The Abu Dhabi-based technology group G42 divested from Chinese companies and formed a strategic investment partnership with Microsoft. The chief executive officer of Alat, the new company backed by the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) and charged with making Saudi Arabia a global hub for electronics and advanced industries, indicated that the company would make similar divestment decisions if needed to maintain U.S. partnerships.

Meanwhile, China and Russia seek to expand investment linkages with Gulf countries’ sovereign wealth funds (SWFs). While Gulf SWFs’ exposure to Chinese and Russian assets is limited when compared to fund investments in the United States, the United Kingdom, European Union countries, and other Middle Eastern countries, this exposure may be increasing, albeit slowly. Various Gulf SWF officials have indicated plans to increase Asian assets, particularly by focusing on China, including through its gateway of Hong Kong—underscoring the potential for significant strategic shifts. In April 2024, Investcorp, a Bahrain-based investment firm, and the China Investment Corporation launched a platform to invest in high-growth companies across the Gulf and China.

Regarding Russia’s linkages with SWFs, the Saudi PIF and the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) formed a partnership in 2015; the two funds agreed to “identify and act on promising investment opportunities in Russia” in 2017. The RDIF continues to occupy a position in the international investments of the PIF’s portfolio. Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala SWF entered the Russian market in 2013 with plans to be a “long-term investor,” but following the invasion of Ukraine, Mubadala’s chief executive officer said in March 2022 that the fund would pause investments. It appears that Gulf SWFs have refrained from initiating major investments in Russia since the invasion.

In terms of trade, China’s bilateral trade partnerships with Gulf countries are much larger and more complementary than those of Russia. The UAE is a useful case study, as it is a top regional trade partner for both China and Russia. In 2022, the UAE’s exports to China reached $32.5 billion, while China’s exports to the UAE totaled $57.7 billion, according to OEC data. Meanwhile, that same year, the UAE’s exports to Russia only amounted to $2.47 billion, and Russia’s exports to the UAE only registered $8.1 billion (gold and diamonds accounted for 66.4 percent and 20.3 percent, respectively, of the total value of exports).

China’s outsized influence in the Gulf region’s trade flows compared to Russia’s theoretically indicates a greater degree of geoeconomic power. In practice, China’s bilateral trade partnerships with Gulf countries involve a complex web of commercial actors, complicating any broad classification of China’s regional trade ties as concerted collaboration or direct competition with Russia. Yet Beijing is likely to continue pursuing a China-GCC free trade agreement, as the Chinese government views such agreements with major economic blocs as prestige projects. Meanwhile, Russia has made recent progress on trade agreements with Iran, establishing a free trade agreement between the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union and Iran in December 2023.

Multilateral Groupings

Gulf states are becoming increasingly visible participants in multilateral organizations and country groupings where China and Russia possess significant influence, such as the economics-oriented BRICS+ and security-focused SCO. For their part, Gulf Arab states seek greater economic and political clout through participation in these multilateral groupings; however, their governments still want to maintain established partnerships with the United States and Europe. China, Iran, and Russia likewise view BRICS+ and the SCO as multilateral paths toward more economic and political clout in the international system, though these countries’ priorities and relative positions in the global order differ.

In 2023, BRICS extended formal invitations for several new countries to join an expanded bloc. Among the Gulf invitees, the UAE and Iran accepted the invitation and became official BRICS members in early 2024, while Saudi Arabia has neither formally accepted nor declined the invitation. Saudi Arabia is managing a delicate balancing act of foreign relations. Negotiations on a megadeal involving the normalization of Israel-Saudi relations as well as on a potential U.S.-Saudi defense treaty are much higher priorities for Saudi officials than formalizing BRICS membership.

For China and Russia, who each possess clear interests in tapping deep pools of Gulf capital, membership in country groupings and their affiliated entities can offer avenues of cooperation. Indeed, previous Gulf engagement with BRICS includes the UAE’s membership in the BRICS lender, the New Development Bank. This multilateral bank is part of a broader set of de-dollarization initiatives.

Russian influence and interests are easier to discern where the Gulf region and global security fronts intersect. The security-oriented SCO, of which China and Russia serve as founding members, has increased its exposure to the Gulf over recent years. In 2023, Iran became a full member of the SCO, and the Gulf countries of Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE serve as dialogue partners. The Emirati Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation linked the significance of this SCO engagement with his country being “an engaged member of the international community with an unwavering commitment to multilateralism.”

There are also smaller country groupings focused on defense and security cooperation. In March 2024, China, Russia, and Iran held joint naval exercises in the Gulf of Oman. (The countries have staged similar drills several times in past years.) Gulf Arab countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have engaged in joint military exercises, often with Chinese counterparts. Indeed, Gulf countries represent lucrative markets for Russian and Chinese arms exports. However, beyond Iran, it is the United States that serves as the key Gulf partner for defense and security cooperation as well as for arms exports.

Conflict Diplomacy

Middle Eastern conflicts pose both risks and opportunities for Beijing and Moscow and their associated businesses. Before examining Chinese and Russian interests and influence in regional conflicts, it’s important to first understand the Gulf’s stance on these events. GCC states have largely avoided direct involvement in major regional conflicts—excluding the 2017–2021 Qatar-Gulf crisis—but nevertheless remain very concerned about the impact of escalating tensions and conflict, especially stemming from the Israel-Hamas war and related Houthi attacks in the Red Sea. Following the COVID-19 pandemic’s severe economic impact, GCC governments have largely pursued a dual strategy of advancing regional de-escalation and refocusing on domestic priorities. Through these adjusted stances, they have sought to better align foreign policy with economic and business interests; for instance, the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement that led to a resuming of diplomatic relations in 2023 reflects this trend.

Chinese strategic interests are more closely aligned with a stable, rather than conflict-ridden, MENA region. While regional conflicts often offer the Chinese government openings to promote perceived U.S. foreign policy failures or ineffectiveness, and echo Russian government statements in this regard, such official rhetoric is opportunistic rather than reflective of any distinct foreign policy preference toward the region. Advancing a “zero-enemy policy” in the Gulf is more difficult amid conflicts involving the region’s state actors, as evidenced by the Qatar-Gulf crisis. Beijing scaled back cooperation with Qatar during this period to avoid jeopardizing ties with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The Israel-Hamas war has likewise placed Beijing in an uncomfortable position concerning its long-standing ties with both Israelis and Palestinians.

The trajectory of regional conflicts rarely presents amenable conditions for the win-win cooperation and development-focused engagement promoted by Beijing. Many concerns about Chinese actors jumping into regional power vacuums and eagerly embedding themselves in postconflict stabilization and reconstruction processes have proved exaggerated. Tensions that have direct commercial implications, such as the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, have raised costs for shipping and insurance at a time when Chinese companies seek to generate more revenues from overseas markets. Thus, Chinese government and business actors seem to prefer lower-risk, higher-reward engagement with wealthy, stable countries like Saudi Arabia or the UAE.

In contrast, Russian actors generally have less to lose and more to gain through engagement in conflict zones. Russian interventions in Libya and Syria have provided regional leverage and access to economic opportunities. This form of regional engagement reveals a high-risk tolerance. On a broad level, the recent outbreak of major conflicts in the Middle East, such as the Israel-Hamas war and prospects for a wider escalation of the conflict involving Hezbollah or Iran, has shifted some global attention—and associated criticism—away from the battlefield in Ukraine. Yet the Russian invasion of Ukraine and ongoing armed conflict ultimately impose constraints on Moscow’s capacity for active involvement in and exploitation of regional conflicts.

In some limited instances, Russian involvement in Middle Eastern conflicts overlaps with specific Gulf interests in North Africa and the Levant. Yet this dimension of Russia’s role in the region largely clashes with the foreign policy approaches and longer-term interests of Beijing and other key regional actors. China’s long-standing policy of nonintervention is at odds with Russian behavior in Ukraine and the Middle East and thus requires a strategic framing to reconcile continued Chinese support for Russia in these domains. Chinese economic ties with wealthy, stable countries have flourished, whereas those with poor, conflict-ridden countries have not. Persistent regional conflicts and tensions ultimately pose longer-term challenges to the ambitious economic diversification and development processes underway in Gulf Arab countries.

Yet conflict mediation efforts present opportunities for both Chinese and Russian governments to flex their diplomatic muscles. The Beijing-brokered agreement between Saudi Arabia and Iran in March 2023 served as a major diplomatic triumph for China. According to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “in-depth communication” from Xi and “strong support from China” led not only to one agreement but to a “‘wave of reconciliation’ across the Middle East.”

In zero-sum thinking, the Chinese diplomatic win through brokering the Saudi-Iranian agreement represents a loss for Russia’s mediation ambitions. The Russian president’s spokesperson said in October 2023 that “Russia can and will play a role in the resolution [of the Israel-Hamas conflict],” suggesting an opportunistic approach to mediating other Middle East conflicts beyond the Gulf. So far, however, it is Gulf countries that have played a more active role in mediating Russia’s conflicts than the other way around. For example, Riyadh hosted peace talks on Ukraine in August 2023 but did not invite Russian delegates. Earlier in August, Saudi Arabia and Türkiye led negotiations between Ukraine and Russia on prisoner swaps and maritime agreements. Mediation efforts by the UAE also led to a large prisoner of war exchange in early 2024. In this sense, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has enabled Gulf governments to increase their international profile as conflict mediators.

Different Trajectories

Across the Gulf region, China and Russia have uneven levels of influence, various strategic interests, and different capabilities to achieve these interests. The region, which itself represents a diverse array of state actors, does not occupy a top-tier position in the foreign policy priorities of either Beijing or Moscow. Yet it would be a mistake to think that Chinese and Russian engagement—in its multifaceted forms—does not possess significant implications for Gulf countries. China and Russia maintain and seek key economic ties with various countries, participate in region-focused multilateral groupings, and pursue conflict-related diplomacy.

The purpose of this article was not to take a comprehensive, in-depth look at China and Russia relations in the Gulf, but rather to highlight and assess some clear indicators of their interests and influence and provide a frame for understanding their evolving relationships. For example, large flows of Chinese and Russian tourists and high-net-worth individuals into the Gulf are certainly visible indicators of influence. However, beyond government mechanisms like China’s Approved Destination Status scheme for tourists, these people flows are driven largely by meso- and micro-level considerations and are therefore difficult to link directly to the state-led pursuit of strategic interests. While Chinese and Russian officials surely want to promote more robust corridors between their countries and the region, it is decidedly not in their interests to see large outflows of human and financial capital finding a long-term home in the Gulf.

There are few clear examples of active cooperation between Beijing and Moscow in the Gulf—thus resonating with findings from other comparative analyses on the approaches adopted by China and Russia to raise their regional profile. Both governments possess overarching, overlapping interests linked to fostering a broad coalition of Global South countries, and deeper ties with Gulf countries can advance these interests. China enjoys a stronger economic foundation in the region, generally has more to offer Gulf countries through multilateral groupings (though Beijing is cautious about defense and security cooperation), and is gradually expanding its noneconomic influence through diplomatic wins such as the Saudi Arabia-Iran deal in 2023. Russia operates upon a weaker economic foundation in the Gulf, generally has less to offer Gulf countries through multilateral groupings (though is more inclined to intervene in MENA conflicts), and somewhat ironically has provided a platform for Gulf countries to enhance their mediation credentials.

Ultimately, China and Russia face different future trajectories in the Gulf. Driven by the motivations of government, economic, and other actors, China has a more significant and expansive role to play across the region should the country’s key actors decide to fill. By comparison, Russian actors will likely continue to be confined to a narrower, limited role. These positions and trajectories will be shaped by the prevailing interplay of strategic interests and influence, which continue to evolve and can also shift abruptly. The two countries’ dynamic set of relations will therefore require continual monitoring and constant reassessment—especially for government officials in Washington interested in either bolstering U.S. leadership in the region or managing its decline.

In this series on Russia in the Middle East and North Africa, Carnegie scholars and external experts analyze how Russia has used various foreign policy tools to mount a recent comeback in the region after years of absence following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Contributors to the series also examine the impacts of Russian policies on questions of peace, security, and democratic development in the Middle East and North Africa.

.jpg)