Editor’s note: Prior to joining Carnegie, the author served for three years as President Joe Biden’s top migration adviser in the National Security Council, where she spearheaded the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection discussed in this paper.

Introduction

This June marked two years since U.S. President Joe Biden and twenty of his peers stood on stage together in Los Angeles and ushered in a new migration pact for the Western Hemisphere. The adoption of the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection (LA Declaration) was a rare and unifying moment in the Americas and offered a collective answer to the challenge overtaking the entire region in 2022.1 In the United States, it also signaled a shift from the traditional focus on the U.S.-Mexico border to a hemisphere-wide approach to managing migration.2

By June 2022, 6 million Venezuelans had fled their country. Today, that number has reached 7.7 million, making Venezuela’s refugee and migration crisis the largest in the world, outpacing even Ukraine and Syria.3 Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, most displaced Venezuelans settled in South America. When public health orders lifted and borders reopened in 2021, this fundamentally changed. While North America’s economies rebounded quickly, the pandemic hit Latin America and the Caribbean harder than any other region in the world.4 Migrants were among the first to lose their jobs. This dramatically shifted migration patterns in the Western Hemisphere. Left without opportunity in South America, Venezuelans and other migrant populations started to brave the seemingly impenetrable Darien Gap, the dense jungle between Panama and Colombia that separates South and Central America,5 and transnational criminal organizations were more than willing to profit from facilitating their passage. Soon, nearly every country in the region was overwhelmed.

The adoption of the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection was a rare and unifying moment in the Americas and offered a collective answer to the challenge overtaking the entire region in 2022.

Moments like this create incentives for countries to become insular and advance policies that benefit their citizens at the expense of their neighbors. This can create more chaos and secondary migratory movements. In 2022, leaders of the Western Hemisphere chose instead to come together under the LA Declaration. This paper traces the events that led to the adoption of the LA Declaration in June 2022 and analyzes the impact of its three-pronged approach, which focuses on (1) stabilizing displaced populations where they were, (2) expanding legal pathways for migration, and (3) humane border enforcement. The paper will also consider the role U.S. leadership played in making the LA Declaration happen.

In 2024, two years after its signing, countries have largely embraced the LA Declaration as a concept for shared responsibility and cooperation on what is ultimately a hemispheric challenge.6 Governments are no longer washing their hands or actively facilitating the flow of migrants to North America. There is recognition that every country is impacted and that the solution to a shared challenge is a shared response.

The LA Declaration is also starting to shape the global response to migration. In June, the world’s top economic leaders adopted the LA Declaration three-pronged approach at the G7 Summit in Italy.7 This marks a significant achievement for Biden and for leaders across the Western Hemisphere who dared in the summer of 2022 to put aside differences and work together. Collectively, they launched a model for responsibility-sharing that is beginning to shape the global migration response.

With global displacement at an all-time high in 2024,8 the United States and all countries will continue to need strong domestic immigration policies to ensure an order response at their borders and in their communities. The LA Declaration is not a substitute for domestic actions. Rather, it serves as a foreign policy complement to multiply the impact of these actions. For instance, as the United States takes steps to further increase border enforcement, open new immigration pathways, and grant work permits to newcomers, it is in the U.S. interest for Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and every country in between to take similar actions.

During a recent interview, Amy Pope, the new director general for the International Organization for Migration, said, “We very rarely see migration policy embedded in foreign policy. And frankly, that’s where it better belongs.”9 The LA Declaration is just that—a foreign policy approach to managing migration and a force-multiplier for domestic efforts.

- Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar,

- Dr. Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall,

- Christopher S. Chivvis

Background

At a different time, under different circumstances, it is unlikely that twenty-one leaders from the Western Hemisphere would have reached consensus on an ambitious new migration pact, especially after only nine months of negotiations. The last time a plurality of the Western Hemisphere came together in this way on migration was in 1984, when ten countries signed the Cartagena Declaration on Refugees.10 The Cartagena Declaration responded to the civil wars in Central America that had sparked a large-scale refugee crisis in the 1980s.11 The adoption of the LA Declaration in June 2022 was the result, in part, of another crisis moment in the Americas.

In contrast to other parts of the world, there is a strong spirit of solidarity in the Americas and a tradition of welcoming one’s neighbors.12 When Venezuelans started leaving their country in large numbers around 2015 (see box 1), South American governments did not set up camps to isolate and exclude Venezuelans from the general population. Instead, most opened their doors and welcomed Venezuelan children into their schools. Thanks to favorable nationality laws across Latin America, the children born to Venezuelan migrants were granted the citizenship of their host countries, with all the commensurate rights and privileges.

Colombia has been the top host country for Venezuelans and provided safe haven to around 2 million by 2020. Millions more settled in places like Ecuador, Peru, Chile, and Brazil. Those fleeing to North America during the early years of the crisis were largely wealthier Venezuelans who had passports, visas, and family connections there. Very few Venezuelans dared to traverse the dangerous Darien Gap.

The Cartagena Declaration responded to the civil wars in Central America that had sparked a large-scale refugee crisis in the 1980s. The adoption of the LA Declaration in June 2022 was the result, in part, of another crisis moment in the Americas.

Box 1: Brief History of the Venezuela Refugee and Migration Crisis

For decades, Venezuela was among the top economies in Latin America. During the 1980s and 1990s, Venezuela served as a safe haven for millions of refugees fleeing conflicts in other parts of the region, like Colombia and Chile. The prosperous country also attracted immigrants from Europe and other parts of the world. Over the course of the 2000s, Venezuela fell into economic and political turmoil. By 2014, the price of oil plummeted. Declining energy prices, combined with economic mismanagement and a slide toward authoritarianism, sent the country into an economic and political crisis and prompted Venezuelans to start leaving the country in large numbers around 2015.13

The tipping point came on March 29, 2017: Venezuela experienced a constitutional crisis. In January of that year, there was a series of protests against the Nicolás Maduro regime after it arrested key opposition leaders. In March 19, 2017, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice dissolved the opposition National Assembly. By the end of 2017, over 1.6 million Venezuelans had fled the country.14 Venezuela’s 2018 elections, which extended Maduro’s time in power for another six years, were widely condemned by the international community as falling far short of free and fair standards.15

By the end of 2018, the number of refugees and migrants from Venezuela worldwide reached 3 million.16 By March 2020, when the pandemic hit, the number had soared to over 4 million.17 This matched the scale of the Syrian refugee crisis. In both situations, nearly half a billion people fled their country in the first four years of the crisis, and most settled initially in neighboring countries.18

Migration trends in the Western Hemisphere changed dramatically in 2020. Not only did the coronavirus pandemic bring global commercial travel to a halt, it also temporarily froze migration movements around the world. Governments closed their land borders on public health grounds, and with few exceptions, migrants and refugees stayed where they were.19

A year later, most governments had reopened their borders, and migration resumed, but the landscape had dramatically shifted. Many Venezuelans and other populations that had settled in South America were uprooting for a second time, and many were looking north.

In the wake of the pandemic, three economic realities contributed to the shift in migration trends.

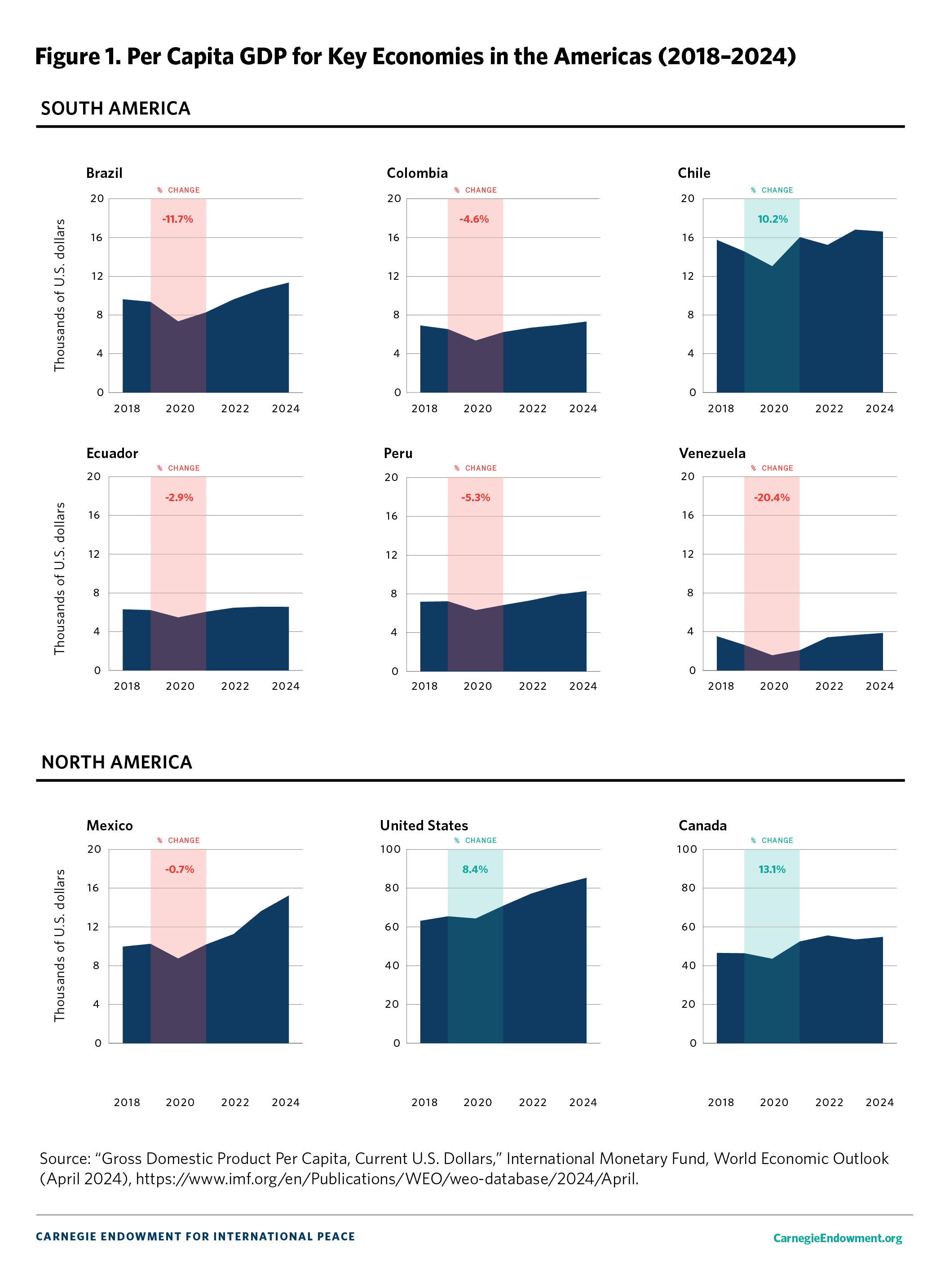

First, the economic situation in Venezuela turned from bad to worse. Venezuela’s gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by 20 percent during the pandemic (see figure 1). This eclipsed the hope of Venezuelans to return home and caused millions more to flee the country.20

Second, South American countries hosting the majority of Venezuelans also suffered major economic hardships (see figure 1).21 From 2019 to 2021, Colombia’s per capita GDP contracted by 4.6 percent, Peru’s by 5.3 percent, Ecuador’s by 2.8 percent, and Brazil’s by 11.7 percent.22 Chile is the only top host country that fared well economically, with over 10 percent per capita GDP growth from 2019 to 2021.

Meanwhile, the economies of North America rebounded quickly from the pandemic, especially compared to South America. In fact, from 2019 to 2021, the U.S. economy grew by 8.38 percent and Canada’s grew by 13.1 percent. Mexico’s per capita GDP dropped during this period, but by only 0.7 percent.23 This means that as more and more migrants in South America were losing their jobs in 2021, North America was generating more jobs than they could fill.

The pandemic exacerbated long-standing economic and political challenges not only in Venezuela but also in various other pockets of the Western Hemisphere, including Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and northern Central America. In July 2021, Haiti’s president Jovenal Moïse was assassinated, plunging the country into even more insecurity.24 Across the region, there was an uptick in violence and crime in the wake of the pandemic.25 In short, the Western Hemisphere had all the necessary conditions for migration 2021.

During this period, criminal actors were quick to capitalize on the growing migration flows. Some of the top Latin American cartels that had long been involved in the illicit drug trade added migrant smuggling to their business.26 Leveraging social media platforms, smugglers started to advertise the dangerous Darien jungle as a tourist attraction. As one New York Times journalist described it, “Every step through the [Darien] jungle, there is money to be made.”27 Since 2021, hundreds of thousands of migrants have signed up and paid enormous fees to traverse the Darien Gap and have faced unimaginable horrors—wild animal attacks, disease, sexual assault, and even death.28

In 2021, there was one more major change in the Western Hemisphere—a new U.S. president who restored the nation’s long-standing tradition of welcoming refugees and immigrants. Along with continued job growth and vaccine prevalence, this contributed to a post-pandemic shift in migration trends. Refugees and other migrants move where the jobs are, and in 2021, the jobs were north of the Darien Gap.

A flashpoint for the entire region was in September 2021, when a group of around 15,000 Haitians moved north from Brazil and Chile, through the Darien Gap, across Central America and Mexico, and arrived at the remote U.S. border town of Del Rio, Texas.29 The group congregated under a bridge at the border, creating a major humanitarian situation that was difficult for both Mexico and the United States to manage. By and large, the Haitian migrants were not coming directly from Hispaniola. They had settled in South America after the 2010 earthquake. Like their Venezuelan counterparts, Haitian migrants living in South America were among the first to lose their jobs during and after the coronavirus pandemic.

The Del Rio incident was a wake-up call. Migration trends were shifting, and old playbooks and policies would not be sufficient. There was growing consensus that a new, hemisphere-wide strategy was needed. Building one would require leaders to come together.

The Del Rio incident was a wake-up call.30 Migration trends were shifting, and old playbooks and policies would not be sufficient. There was growing consensus that a new, hemisphere-wide strategy was needed. Building one would require leaders to come together.

The Proposal

In the wake of the Del Rio incident, Biden’s national security team drafted the original proposal for a regional migration pact in late September 2021. Conveniently, Biden was slated to host two major summits with regional leaders in the coming year—the next North American Leaders’ Summit and the Summit of the Americas.

The proposal recommended that the president use the upcoming summits to launch a forward-leaning regional migration framework that would incentivize responsibility-sharing and establish a set of a common principles for migration management. Mobilizing more economic support for frontline migrant host countries was a top priority, essential to stabilize migration and prevent the secondary movements that had started from Brazil and Chile.31 The proposal also focused on the need to expand formal immigration pathways and increase border enforcement across the region. In 2021, only a few governments, such as Panama, Mexico, and the United States, were deploying significant personnel to their borders to deter irregular migration.

In the beginning of October 2021, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan convened an internal meeting with cabinet members in the White House Situation Room to consider the proposal for the new migration pact. The team debated whether a multilateral agreement of this magnitude could be negotiated on such a tight time frame. After all, the Summit of the Americas was just nine months away. Some doubted that left-leaning leaders in Latin America would sign onto a document that the United States initiated. Others had confidence that the migration challenge would unify leaders, despite their ideological differences. In the end, the team agreed to move forward with the proposal, Biden signed off on the plan, and the negotiations for a regional migration pact commenced.

Homeland Security Advisor Liz Sherwood-Randall and her team spearheaded the effort from the White House. They quickly got to work drafting the initial text of the pact and developing a diplomatic strategy for negotiating it. Within the U.S. government, the Vice President’s Office, the State Department, Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Treasury Department each played key roles as well.

The Negotiations

North America

The first step for the Biden team was securing support from their neighbors to the north and south. On November 18, 2021, the U.S. president welcomed Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to the White House for the first North American Leaders Summit since 2016. The joint gathering was significant for many reasons, including strengthening economic and security cooperation and coordinating on the ongoing COVID-19 response. On migration, the summit unified the three leaders around a common vision. In the joint statement, which was negotiated in advance, the three leaders called on the rest of the region to “join us to address the challenges of unprecedented migration through a bold new regional compact on migration and protection.”32

Colombia

With Canada and Mexico on board, the Biden team pivoted to secure buy-in from other key players in the region. At the top of the list was Colombia. Since the beginning, Colombia had been a leader in the regional humanitarian response to the crisis in Venezuela. Most notably, former president Iván Duque announced in January 2021 that Colombia would grant temporary protected status to 1.8 million Venezuelans living in the country for a period of ten years.33 This was met with international praise,34 including from Pope Francis and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi, who called it “one of the most important humanitarian gestures made on this continent [for decades].”35 Later, Duque reflected that “We did it out of conviction. [The Venezuelans] were invisible, they couldn’t open an account, they couldn’t work, they couldn’t enter the health system. They were practically like a community without a future.”36

Biden’s team knew that any hemisphere-wide migration pact would need Colombia’s strong endorsement, and it would also need to be directly responsive to Colombia’s needs. With a 4.5 percent contraction in Colombia’s GDP following the coronavirus pandemic and nearly 2 million Venezuelans living in the country, communities across Colombia were struggling.37 Without more international support, there was a risk that the country’s welcoming policies would erode over time.

On March 10, 2022, Biden hosted Duque at the White House. By the time the two presidents met, their teams had already been talking for months, and Colombia was a strong supporter of the proposed migration pact. As a symbolic gesture, Biden used this moment, sitting across the table from the Colombian president in the Cabinet Room, to make a public call to action to the rest of the Americas:

“Our hemisphere migration challenges cannot be solved by one nation and—or any—and any one border. We have to work together. And so, today, I’m calling for a new framework of how nations throughout the region can collectively manage migration in the Western Hemisphere. There’s something we’ve been discussing with partners throughout the region, including you, Mr. President. And our goal is going to be to sign a regional declaration on migration and protection in June in Los Angeles when the United States hosts the Summit of the Americas.”38

A Hot Spring

Following the Biden-Duque meeting at the White House in March 2022, negotiations went into high gear. The three-month time frame to finalize the deal was unprecedented, but it matched the urgency of the moment: in the spring of 2022, migrant crossings through the Darien Gap were soaring, with many young children making the perilous journey. The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reported that over 2,000 children crossed the jungle in May 2022, up from 500 children in May 2021.39 Increasing numbers of Nicaraguans were also fleeing their country, and boat departures from Cuba and Haiti were up. This was translating into record migrant encounters at the U.S. land and maritime borders.40

Meanwhile, the debate in Washington over how the Biden administration should respond to the mounting migration challenge grew more and more heated.41 This mirrored debates in capitals across the hemisphere. In Costa Rica, for instance, migration was a top campaign issue in the national presidential elections that took place in February 2022.42 Newly elected Chilean President Gabriel Boric, who campaigned on a liberal approach to migration, faced major pressure in early 2022 to maintain the restrictive migration policies of his predecessor in light of a stagnating economy and a migration influx at the country’s borders.43

The Sprint to the Summit

Five days after the Biden-Duque meeting at the White House, Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas traveled to Mexico and Costa Rica to discuss the migration challenge and shore up support for the regional pact.44 In April and May, the United States and Colombia took turns hosting in-person meetings with a core group of countries to finalize the text of the pact.45 They also convened consultations with the United Nations, civil society groups, and regional experts. Securing the United Nations’ endorsement was viewed as particularly key.46 The UN Refugee Agency and the International Organization for Migration each have a long tradition of working with Latin American governments to respond to refugee and migration challenges. Their support and advocacy for the pact gave it credibility, especially for leaders who were skeptical that the United States was motivated by its own national interests and border security priorities.

During this period, the Biden team also consulted members of Congress on the proposed migration pact. Following a series of briefings, the Congressional Hispanic Caucus sent a letter to Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken on May 31, 2022, applauding the overall initiative but urging the administration to negotiate “clear language on the protection of vulnerable migrants” including children, pregnant women, elderly people, LGBTQ migrants, and those with chronic disability and illness.47 The caucus’s feedback mirrored input from various governments and civil society groups, and it was incorporated into the final text.

Securing the Final Endorsements

Notwithstanding the urgency of the moment, the Biden team did not expect as many countries to sign on as eventually did. During the final two weeks of planning for the Summit of the Americas, Principal Deputy National Security Advisor Jon Finer convened daily planning meetings in the Situation Room. Nearly every day, the migration team reported another new endorsement. It looked like the total might reach sixteen, or maybe seventeen, signatories. No one predicted twenty-one, a plurality, or two-thirds, of the thirty-one countries that attended the 2022 Summit of the Americas. Reaching that level of consensus on a topic as politically sensitive as migration far surpassed initial expectations in the White House.

Reaching that level of consensus on a topic as politically sensitive as migration far surpassed initial expectations in the White House.

Vice President Kamala Harris was instrumental in securing key Caribbean endorsements. In April 2022, she convened sixteen Caribbean leaders in preparation for the Summit of the Americas. In Los Angeles, she met with them again. These two events generated a slate of Caribbean endorsements, including Barbados, Belize, Haiti, Jamaica, and Guyana.48 A few key Caribbean countries ultimately withheld their support for the pact, including the Bahamas, the Dominican Republic, and Trinidad and Tobago, each citing domestic sensitivities on the topic of migration.

Securing Brazil’s endorsement had always been a top priority for the Biden team. Like Colombia, Brazil had been a leader in the Venezuela response from the beginning and had launched an innovative program called Operation Welcome to relocate Venezuelans throughout the country and match them with jobs. By 2022, Operation Welcome had become a regional model.49 However, in 2022, Brazil was going through a presidential election, and the Jair Bolsonaro administration was reluctant to join a new multilateral framework. His administration, which was supported by the industrialist and logging communities, was also opposed to any reference in the text that linked migration to climate change. For other delegations, particularly the Caribbean countries, having climate language in the text was important (see box 2). In the end, Brazil agreed to endorse the declaration, and Bolsonaro stood on stage with his peers. Climate language was omitted from text itself, but addressing the climate-migration nexus has remained a priority during implementation.

Box 2: The Climate-Migration Nexus in the Americas

Research shows that Latin America and the Caribbean are disproportionately impacted by the adverse effects of climate change.50 For example, sea levels in the region are rising at a faster rate than globally, and the region has faced deforestation, droughts, and extreme weather events. Vulnerability to climate shocks have led many Latin Americans to leave their home countries,51 and according to the World Bank Group, without urgent climate action, Latin America could have 17 million climate migrants by 2050.52

Brazil was not the only South American country that was slow to endorse the declaration. Some others, like Argentina and Peru, voiced concerns about the informality of the consultation process and worried about duplication. They argued that there were already existing subregional migration frameworks in place that met their needs, like the Quito Process and the South American Conference on Migration. Other countries in the Americas emphasized that the new regional migration pact was meant to complement, not replace, existing subregional mechanisms. To reassure these countries and gain their signatures, participants agreed to include a full section at the end of the text referencing existing global and subregional frameworks and stating that the LA Declaration “builds upon” these existing efforts and international commitments.

López Obrador’s last-minute decision not to attend the Summit of the Americas briefly put Mexico’s endorsement into doubt.53 Mexico had been an early champion of the effort and had played a key role in shaping it substantively. López Obrador’s team was quick to clarify that their leader’s absence from the summit did not diminish Mexico’s support for the migration pact.54 In the end, then Mexican foreign secretary Marcelo Ebrard stood in for López Obrador at the LA Declaration signing ceremony. Mexico also announced an ambitious set of commitments in conjunction with the adoption. A month later, Biden hosted López Obrador at the White House, and they jointly reaffirmed their support for the LA Declaration.55

In addition to López Obrador, the Honduran, Guatemalan, and Salvadoran heads of state each boycotted the Summit of the Americas. However, like Ebrard, their foreign ministers stood in for their leaders at the LA Declaration signing ceremony to vouch their country’s support.

Putting Skin in the Game

For the Biden team, it was critical that the migration pact be more than just words on paper. It needed to spark immediate, coordinated action to address the crisis at hand. With this in mind, the State Department conveyed through its embassies that no leader planning to endorse the LA Declaration should come empty-handed. Each adopting country was expected to put some skin in the game in line with the three pillars: stabilization, expanded legal pathways, and humane border enforcement.

A top ask related to the stabilization pillar. In bilateral calls and visits, U.S. leaders urged governments to come to Los Angeles prepared to announce new policies to grant legal status to migrants living in their country, following Colombia’s example in 2021. At the same time, the United States was urging donor countries like Canada and Spain, as well as the international financial institutions like the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank, to identify additional economic support that could be surged to the frontline host countries in the region that were taking positive steps on stabilization. Another top ask was for countries to establish new labor and humanitarian visa programs so that migrants would have more options to travel lawfully, by plane, to their destination, rather than crossing over borders by foot.

The United States knew it would need to lead by example. In the months leading up to the summit, the National Security Council led an intense policy process to identify “big-ticket” commitments that Biden could announce in line with the goals of the declaration’s three pillars.

In the end, countries really delivered. Notable mentions go to Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Belize, three countries that announced sweeping new national policies to offer legal status to hundreds of thousands of migrants living in their countries. This was directly in line with the goals of the stabilization pillar. In turn, Biden announced an additional $25 million to the World Bank’s Global Concessional Financing Facility “to prioritize countries in Latin America such as Ecuador and Costa Rica in their newly announced regularization programs.”56

In the end, countries really delivered. Notable mentions go to Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Belize, three countries that announced sweeping new national policies to offer legal status to hundreds of thousands of migrants living in their countries.

Under the legal pathways pillar, Mexico emerged as a leader, announcing new labor pathways for Central America that would collectively benefit over 40,000 individuals.57 In the final days of negotiations, Guatemala also came forward with a commitment to advance new legislation to promote legal labor migration programs. The United States, Canada and Spain made significant announcements on legal pathways in Los Angeles.

Under the enforcement pillar, Washington announced a new counter-smuggling “sting operation,” including the deployment of 1,300 personnel and $50 million to support governments in the region to arrest and prosecute criminal smugglers. This operation expanded upon the counter-smuggling efforts Harris launched in 202158 to disrupt the “multi-billion dollar smuggling industry” that was fueling the migration surge through the Darien Gap and across the hemisphere in 2022.59

Box 3: The U.S. Women Who Made the Deal Happen

To realize the president’s vision for a regional migration pact, Homeland Security Advisor Liz Sherwood-Randall and her team spearheaded the effort from the White House. Over the course of nine months, Sherwood-Randall convened a series of cabinet-level meetings to ensure the entire U.S. government and diplomatic corps was advancing the most ambitious version of the framework possible. She kept the president and vice president regularly updated on developments. Under the Barack Obama administration, Sherwood-Randall led a similar process to bring a set of diverse world leaders together on the topic of nuclear security.

Another key figure was Julieta Valles Noyes, who was sworn in as the assistant secretary of state for population, refugees and migration (PRM) on March 31, 2022, just three months before the Summit of the Americas. In the final months of negotiations leading up to the Summit of the Americas, she worked the phones, convened consultations, and brought a team out to Los Angeles. They worked around the clock to finalize negotiations and secure the final set of endorsements. Other women who were instrumental in the LA Declaration negotiations were Emily Mendrala, Marta Youth, Marcela Escobari, and Serena Hoy.

Marta Youth, Emily Mendrala, Julieta Valles Noyes, Katie Tobin, Liz Sherwood-Randall, and Marcela Escobari (left to right) at the Los Angeles Declaration adoption ceremony on June 10, 2022. (Photo by Clay Alderman, who also played a key role.)

The Main Event

On the afternoon of June 10, 2022, twenty-one leaders stood on a stage together in downtown Los Angeles, sending a signal to the world that the hemisphere was united in purpose to address the unprecedented challenge of migration.60 In addition to the twenty-one leaders from the Americas, several European countries attended the launch event as observers. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi and then director general of the International Organization for Migration António Vitorino also attended, signaling the UN’s strong support.

Biden opened the ceremony by announcing, “With this declaration, we’re transforming our approach to managing migration in the Americas. Each of us is signing up to commitments that recognize the challenges we all share and the responsibility that impacts all of our nations.”61 Afterward, Biden gave the floor to then president Guillermo Lasso of Ecuador, who applauded his peers for the “political will” to confront the challenge together.62

Heads of delegation gather to adopt the LA Declaration on Migration during the 2022 Summit of the Americas. (Photo by the White House)

Reactions From the Media, Congress, and Policy Experts

In general, the LA Declaration received a positive reception from both domestic and international audiences. The Associated Press hailed the LA Declaration as “perhaps the biggest achievement of the Summit of the Americas.”63 La Nacion, a top news outlet in Latin America, called the declaration “a sign of unity and progress.”64 The Economist reported that the LA Declaration is “stimulating new thinking” and is “a first effort to set out some common principles.”65 Fox News, usually critical of the Biden administration on migration and border policies, reported simply that, “Biden unveils migration declaration with Western Hemisphere, decries ‘unlawful migration.’”66 Other U.S. news outlets, like Time and Bloomberg, were more critical, focusing on the fact that the declaration was nonbinding and highlighting the absence of the Mexican, Honduran, Guatemalan, and Salvadoran heads of states.67

Congressional Republicans largely did not react to the declaration’s launch. The Congressional Hispanic Caucus, which is primarily comprised of Democrats, issued a statement calling the pact a “step in the right direction.”68 The caucus’s chair, California Democrat Raul Ruiz, remarked that it “will transform our approach to managing migration in the Americas.”69

The LA Declaration also received praise from foreign policy experts who focus on the Western Hemisphere. Andrew Selee, the president of the Migration Policy Institute, called the declaration a “big step for real migration cooperation across the Americas.”70 Similarly, in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Theresa Cardinal Brown, the immigration director for the Bipartisan Policy Center, called it “a big deal” and said, “If it was just about [the United States], it wouldn’t happen.”71

The LA Declaration was “a big step for real migration cooperation across the Americas” according to Andrew Selee, the president of the Migration Policy Institute.

Others expressed doubt that the pact would have any impact. Simon Hankinson of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative policy think tank, criticized the declaration for promoting “yet more legal pathways” without doing enough on border enforcement.72 The director of the Center for the United States and Mexico at Rice University’s Baker Institute in Texas, Tony Payan, remarked that “no matter how well intentioned [the LA Declaration] may be, [its] words will fade away with little to no accomplishments.”73 One point of agreement among proponents and critics of the LA Declaration was that the real test would be implementation.

Building the Architecture for Implementation

The day after the LA Declaration adoption ceremony, Biden directed his national security team to move immediately to honor the specific commitments he made and to ensure that other countries did the same. He was intensely focused on results.

The first action was a high-level visit to Costa Rica, led by White House staff.74 Biden recognized Costa Rica in his remarks in Los Angeles and vouched U.S. support to manage the influx from Nicaragua.75 The Biden team viewed it as important to deliver quickly for Costa Rica to both address the urgent needs on the ground and generate positive peer pressure in the region. The goal was to incentivize other countries to take similar steps to stabilize the flow.

Within six months, Costa Rica honored the commitment President Rodrigo Chaves made in Los Angeles and started to implement a new, complementary protection policy to give legal status to hundreds of thousands of migrants. In parallel, the United States delivered on the president’s financial commitment to support Costa Rica. Specifically, in February 2023, the World Bank approved a $370 million concessional loan for Costa Rica, which included a $20 million grant from the United States.76

In the first couple of months following the summit, Biden’s team also worked with its counterparts across the region to craft an implementation plan, focused on accountability.

In the first couple of months following the summit, Biden’s team also worked with its counterparts across the region to craft an implementation plan, focused on accountability. On September 27, 2022, Sherwood-Randall and Sullivan co-convened representatives of the LA Declaration signatory countries at the White House to reach consensus on the plan.77 Each country agreed to appoint a “special coordinator” to shepherd implementation. The Biden administration decided to designate a senior official from the National Security Council to represent the United States, sending a signal that the LA Declaration is a top White House priority. The position was initially held by the author, and later Marcela Escobari, a Biden political appointee who first served at USAID and joined the National Security Council in April 2024. Many governments followed suit, appointing individuals in senior political positions within their executive office or foreign ministry. The group also agreed to establish eleven “action packages committees,” each owned by one or two endorsing countries. The implementation plan was formally endorsed at the ministerial level in Lima, Peru the following month.78

Since September 2022, the LA Declaration special coordinators have met regularly, sometimes in person but more often virtually. During these meetings, they report on progress under each action package (see box 4), provide policy updates from their countries, share information on migration trends, and prepare for higher-level meetings.

In the last two years, there has also been a regular cadence of ministerial-level meetings under the LA Declaration. Peru hosted the first ministerial meeting in October 2022, just five months after the pact was signed;79 Belize and the United States co-hosted the second ministerial meeting in June 2023; and Guatemala hosted the third ministerial in May 2024.

At this most recent ministerial meeting in Guatemala, countries agreed to launch a secretariat for the LA Declaration. The secretariat will be an independent body that will support the signatory countries, help implement commitments under the three pillars, and organize future events.

Box 4: The Three-Legged Stool for Managing Migration

The LA Declaration calls for joint action under three main pillars80: (1) stabilization, (2) expansion of legal pathways, and (3) humane border enforcement. Below is a brief description of each of the three pillars.

Pillar I: Stabilization

The stabilization pillar (officially called “stability and assistance” in the LA Declaration text) focuses on the importance of anchoring migrants where they are and preventing the kind of secondary migration flows the region experienced in 2021 after the coronavirus pandemic. To achieve this, it calls on host countries to provide access to basic rights and services to migrants, so that they can settle and stop moving. This includes legal status, a work permit, access to education, and housing. Importantly, this pillar also calls on wealthy countries and international financial institutions to mobilize far more economic support for the top host countries in the region. These are the countries that have been welcoming to their neighbors and disproportionately impacted by refugee and migration flows.

Pillar II: Expansion of Legal Pathways

The second pillar of the declaration sought to address the major deficit in humanitarian and labor pathways that existed across the Americas in 2022. Emerging from the coronavirus pandemic, various countries (such as the United States, Mexico, Canada, Costa Rica, Chile, and Brazil) were facing labor shortages and declining birth rates. At the same time, more people were displaced and on the move in the region than ever before in recorded history. During the negotiations, there was broad consensus to include a pillar dedicated to closing this gap and matching migrants with legal pathways.

Pillar III: Humane Border Enforcement

The third leg of the stool is the “enforcement” leg. The fact that twenty-one countries agreed to include this pillar reflects a shift in how Latin American countries approach migration. Historically, the prevailing view in Latin America has been that there is a fundamental right to migrate, and there has been resistance to impose migration controls at land borders. The practical reality of mass migration has caused political leaders in the region to shift their approach in recent years. Under the third pillar, the declaration acknowledges that all countries have responsibility to manage their borders and even conduct returns in certain instances.

Taking Stock Two Years Later: Achievements and Shortfalls

The two-year anniversary of LA Declaration presents an ideal opportunity to take stock of where the framework is having an impact and where it is falling short. The reality is that displacement from Venezuela and other areas of the region persists in 2024. There is also a notable rise in migration to Latin Amercia from other parts of the world, including China and various parts of Africa. This reflects global migration trends. According to the UN Refugee Agency, 117 million people were displaced worldwide by the end of 2023, the highest ever recorded.81

Tackling the underlying factors causing people to flee their country is critical and is the responsibility of all leaders in the region, but it is not the primary focus of this framework. The LA Declaration was conceived as a migration management strategy, meaning that it seeks to create more order and predictability for governments and more protection and opportunity for those on the move. With this in mind, there are several concrete ways in which the LA Declaration is shifting the landscape and having a positive impact on this immense challenge.

Achievements

Five countries launched new legalization policies to stabilize migrants where they are.

Since the LA Declaration was adopted in June 2022, remarkably, five LA Declaration signatories have implemented new policies to give legal status to migrants in their countries. These include Belize, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, and Peru. They joined Colombia and Brazil, which have been leaders on this issue. Over 2 million Venezuelans have obtained legal status under Colombia’s ten-year Temporary Protected Status policy.82 Brazil has welcomed over 500,000 Venezuelans, matching many of them with job opportunities throughout the country.83 Today, millions of migrants in the region can access a job, register their children in school, and rent a home, millions who were not able to do so before the LA Declaration. Undoubtedly, these include would-be migrants that are choosing not to hand over their life savings to traverse the Darien jungle or cross the Rio Grande. In this way, the actions of these five countries are mitigating overall displacement and creating more order across the region.

Hundreds of millions of dollars in new, targeted economic investments for frontline migrant host countries.

In the spirit of responsibility sharing, donor countries and international financial institutions have also stepped up and leveraged millions of dollars to support frontline host countries in the region. For instance, in December 2022, the World Bank approved a $530 million concessional loan for Ecuador with a $30 million grant from Canada and the United States.84 Two months later, the World Bank approved a $370 million loan for Costa Rica with a similar grant from Canada and the United States.85 Since both Ecuador and Costa Rica are middle-income countries, they traditionally would not be eligible for this kind of lending.86

In November 2023, Biden convened a summit at the White House under the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity. During this event, he announced that the United States was joining Canada, Spain, South Korea, and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to make a total of $89 million in new contributions to the IDB’s Migration Grant Facility.87 These funds will also go directly to support countries in the Americas hosting large refugee and migrant populations.

Six countries joined forces to launch a historic expansion of legal pathways under the Safe Mobility Initiative.

The region has also advanced a historic expansion of legal pathways in the last two years, far exceeding the commitments leaders made in Los Angeles. These new legal pathways are creating viable alternatives to unlawful migration for hundreds of thousands of migrants in the region. Most recently, six LA Declaration countries—Canada, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Spain, and the United States—as well as the United Nations partnered in 2023 to launch the Safe Mobility Initiative.88 Under this initiative, migrants in various countries in the region now have the option to register on a virtual platform and be screened for a wide range of legal immigration pathways within a few weeks. Since it launched in 2023, over 250,000 migrants have registered and over 20,000 (over 10 percent) have already been approved to travel legally to the United States as refugees.89

A new “labor neighbors” initiative that was announced in Guatemala in June 2024 seeks to expand labor pathways on a massive scale across the Americas.90 Collectively, these new legal pathway programs are transforming how migration is managed in the Western Hemisphere and providing an example for the rest of the world.

A wave of new cross-border partnerships has launched to increase enforcement.

LA Declaration countries are also partnering to create more order and predictability at their shared borders. In October 2022, four months after the LA Declaration was adopted, the United States and Mexico launched the Venezuela Enforcement Initiative.91 Under the deal, Mexico agreed to accept back Venezuelans who unlawfully crossed into the United States, and Washington announced a new, streamlined legal pathway for 24,000 Venezuelans. Within a week, there was a 90 percent drop in border crossings, and tens of thousands of Venezuelans in the region stopped in their tracks. Many sought to return home voluntarily to Venezuela to apply for the new program there. Two months later, Biden and López Obrador expanded the joint effort, known as the CHNV Initiative, to include Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, as well as Venezuelans.92

The joint U.S.-Mexico border initiatives of 2022 and early 2023 were just the first in a wave of new cross-border partnerships that grew out of the LA Declaration.

The joint U.S.-Mexico border initiatives of 2022 and early 2023 were just the first in a wave of new cross-border partnerships that grew out of the LA Declaration. In March 2023, the United States and Canada announced an agreement to address the migration surge at Roxam Road between New York and Quebec. The deal involved the United States commiting to accept back asylum-seekers who crossed unlawfully into Canada (between ports of entry), a major amendment to the U.S.-Canada Safe Third Country Agreement. In turn, Canada committed to open 15,000 new legal pathways for Western Hemisphere migrants.93 Canada reported the following month that the joint initiative also led to a swift and sustained drop of more than 90 percent in border encounters into Canada.94 Canada also honored its commitment and welcomed over 15,000 additional migrants and refugees in 2023.

The following month, Panama, Colombia, and the United States joined forces to launch a “coordinated sixty-day campaign” in the Darien Gap, under the rubric of the LA Declaration.95 Both Panama and Colombia deployed thousands of additional law enforcement personnel to the Darien Gap under the campaign, targeting criminal groups like Clan del Golfo that were exercising increasing control over in the jungle and making billions of dollars in profits off of the growing human smuggling industry. The Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. military, under the U.S. Southern Command, also deployed personnel and resources to support Panama and Colombia to implement the law enforcement effort.96 While the Darien Gap remains a challenge, the joint campaign is a prime example of how the LA Declaration is creating space for countries to table their differences and work together to tackle the migration challenge.

More countries are conducting repatriations to deter irregular migration.

Conducting repatriations, particularly by air, is very expensive for governments. Doing it in a humane way requires adequate infrastructure and trained staff to interdict, house, conduct protection screenings, and transport migrants home who do not qualify to stay. Two years ago, only a few countries in the Western Hemisphere were investing national dollars in repatriations. Since the launch of the LA Declaration, this is starting to change. Mexico, in particular, has stepped up and has started routinely conducting air and land repatriation flights to a wide range of countries in the region. In late 2022, Panama paid for voluntary return flights of at least 900 Venezuelans after the launch of the U.S.-Mexico Venezuela Enforcement Initiative and started conducting weekly repatriation flights for Colombians encountered in the Darien Gap in 2023 under the Darien campaign.97 In July, Panama and the United States signed a new agreement on repatriations, with the United States announcing $6 million in financial support for the effort.98 Guatemala and Costa Rica have also indicated their willingness to conduct repatriations with financial support from the United States or other donors.99

Shortfalls

Despite the many achievements of the LA Declaration in its first two years, it is falling short in some areas.

Economic investment is insufficient to truly stabilize displaced populations.

As discussed earlier, a major cause of the secondary movements of Venezuelans and other populations in 2021 was the economic crisis that Latin America and the Caribbean suffered after the coronavirus pandemic. Leveraging more targeted economic investment from international financial institutions and the private sector to middle-income host countries is a goal of both the LA Declaration and the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity.100 While steps have been taken under both agreements to draw more investment to these countries, it still falls short of the need.

Various factors have led to a deficit in resources for key migrant host countries in the Americas. First, as discussed above, most of these top host countries in South and Central America are classified as middle or high income and therefore are not eligible for traditional lending from the international financial institutions nor investments from the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). Some experts also point to a lack of ambition and political will to ignite major reforms at the Inter-American Development Bank and DFC that would be needed to mobilize more migration-targeted financing to key countries.101 There is also the long-standing problem of corruption in some of the top host countries in the region, which makes them less attractive for investors. In the last two years, conflicts in other parts of the world have further drawn resources away from the Americas.

One way to address this deficit would be to connect climate financing with migration response.102 Investments could focus on climate prevention and preparedness in the region, such as by targeting hot spots at risk of extreme weather events. According to the United Nations, South America is among the regions with the greatest need for strengthening early warning systems that can help regions adapt to extreme weather.103 Investments could also focus on making Latin American infrastructure more climate resilient.104

Some countries lack political will to do more on border enforcement.

Although a few countries have increased repatriations and border enforcement in the last two years, progress under the enforcement pillar is still lagging. Various leaders in the Americas resist pressure to allocate more resources to enforcement operations—particularly during a period of economic strain, when leaders are more inclined to invest their limited national resources to domestic programs that will have direct benefits for their citizens. Also, some leaders in the region retain the view that migration is a right—a position that overlooks the dangerous reality of the irregular journeys many migrants undertake, such as through the Darien Gap. Moreover, remittances from migrants also yield a substantial economic benefit for countries. This can create a disincentive for leaders to take meaningful measures to reduce migration flows. According to the World Bank, remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean have increased substantially following the coronavirus pandemic—from around $96 billion in 2019 to $156 billion in 2023. For some countries in the region, such as Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador, remittances made up more than 20 percent of their GDP in 2023.105

Aerial view showing migrants walking through the jungle near Bajo Chiquito village, the first border control of the Darien Province in Panama, on September 22, 2023. (Photo by Luis Acosta / AFP)

Migration through the Darien Gap remains a challenge.

A record number of migrants have crossed the Darien Gap in the years following the coronavirus pandemic, and countless innocent lives have been lost. Smuggling networks have earned hundreds of billions of dollars on the backs of these migrants, advertising the Darien as ecotourism. In addition to the humanitarian toll, there is an environmental toll: the large number of people transiting the Darien Gap is destroying the rainforest and contaminating the water source for local communities. It is the responsibility of the entire region to address the grave humanitarian, environmental, public health, and security situation in the Darien Gap.

There are reasons to be optimistic. The Darien Gap was a central topic of discussion at the LA Declaration ministerial meeting in Guatemala in May. Blinken announced new sanctions for maritime boat operators in Colombia that are actively facilitating the mass movement of migrants in the Darien.106 Also, Colombia announced that it will take additional steps to regularize an estimated 600,000 migrants in the country, expanding upon its landmark temporary protected status program.107 Furthermore, there are early signs that Panama’s new president, José Raúl Mulino, who was inaugurated in July 2024, will introduce new measures to reduce irregular migration through the Darien Gap.108

Collectively, these recent actions should help reduce movement through the Darien Gap. However, it is likely that even more coordinated actions by LA Declaration countries will be needed to truly bring the situation under control. Panama and Colombia will need to take the lead, but the whole region needs to support them in finding solutions.109

The Way Forward

On the heels of the Guatemala ministerial meeting in May and the G7 Summit in June, there is growing momentum for the LA Declaration. In the coming months, leaders in the Western Hemisphere will need to work to capitalize on this momentum to jointly confront new and intensified displacement crises in the region, most notably Venezuela.

The July 28, 2024, presidential elections in Venezuela, which many saw as an opportunity for positive change in the country, instead brought new uncertainty and instability. Maduro claimed victory, even though voting tallies indicate that he lost decisively.110 The election has been widely condemned by the international community and international observers as fraudulent and undemocratic, and the United States and numerous other LA Declaration countries have officially recognized the opposition candidate, Edmundo González, as the victor.111

A survey in early July found that 17 percent of Venezuelans planned to leave the country within six months if Maduro took the presidency.112 Migrant activists in the United States are expecting an influx of Venezuelan refugees into South Florida.113 The election is also a lost opportunity for displaced Venezuelans living abroad, who may have returned home if the opposition had gained power and restored hope for a better economic and political future in Venezuela.

In moments like this, the LA Declaration is most needed. To ensure it continues to be an effective and flexible framework for cooperation, signatories should work in the coming year to (1) foster new LA Declaration champions, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean; (2) take more risks and test new ideas, building on recent successes; and (3) globalize their three-pronged approach.

Fostering New Champions

In 2024, new leaders are coming to power in many of the countries that originally adopted the LA Declaration. Panama and Mexico just held presidential elections, and the United States and Uruguay will do so later this year. In order for the LA Declaration to serve as an enduring framework for regional cooperation, it must continuously generate new champions at the highest levels of government.

Guatemala’s new president Bernardo Arévalo recently emerged as a new champion when he hosted the latest LA Declaration meeting in May 2024, just four months after his inauguration. In the coming year, it will be important for other Latin American and Caribbean leaders to step forward to bring leaders together and test bold new ideas to manage the migration challenge.

Guatemala’s new president Bernardo Arévalo recently emerged as a new champion when he hosted the latest LA Declaration meeting in May 2024, just four months after his inauguration.

Mexico is an obvious choice to host the next major LA Declaration event. Mexico has emerged in recent years as a strong regional leader on migration. Under López Obrador, the country took steps to open new labor and humanitarian visa programs, launch its own root causes strategy in Central America, and increase enforcement at its borders. López Obrador has also urged other countries to do more, including the United States. Hosting the next LA Declaration event would be a way for Mexico’s incoming leader, Claudia Sheinbaum, to send a strong message that Mexico will continue to be a regional leader on this issue. Colombia is another strong option, as an original champion of the LA Declaration and a long-standing regional leader on migration.

Bringing the Dominican Republic on board as an LA Declaration signatory will also be important, particularly as the host of the next Summit of the Americas in 2025. The Dominican Republic is significantly impacted by migration from Haiti and other parts of the Caribbean and could benefit from being part of a regional framework that explicitly prioritizes support for top host countries.

Taking Risks and Testing Ideas Together

Some of the initiatives LA Declaration countries have tested together since 2022 have had an unexpected and dramatic impact on reducing irregular migration. The CHNV Initiative that the United States and Mexico launched in January 2023 is perhaps the best example. It proved the concept that pairing expanded legal pathways with strong border enforcement can drastically reduce unlawful border crossings. Efforts to prioritize economic investment for top host countries are also having a positive impact, resulting in a wave of countries taking actions to integrate migrants and stabilize migration.

These positive outcomes should give LA Declaration leaders confidence to take more risks and do even bigger things together in the coming years to manage the migration flows. At the closing of the LA Declaration ministerial meeting in Guatemala in May, U.S. Special Coordinator Marcela Escobari encouraged her peers to do just this.114 She said,

“What I see around this table is an emerging ‘Coalition of the Brave’—governments making hard decisions for the good of their countries, and our region, and in rejection of xenophobia and the politics of hate . . . Our joint progress should be a source of pride and continued collaboration for the good of all our citizens.”

Globalizing the Three-Pronged Approach

With record levels of displacement globally, migration has become a vexing challenge and political lightning rod for nearly every government. Migration was a hot topic in the EU parliamentary elections earlier this year, and it is polling as a top issue for U.S. voters in November.115

At the G7 Summit in Italy in June of this year, migration was on the agenda for the first time in the group’s history.116 During the summit, leaders adopted the LA Declaration’s three-pronged approach to collectively manage migration. The approach provided a more humane and balanced rebuttal to the enforcement-only approaches pursued by some world leaders in recent years. For instance, various European leaders have pursued arrangements with African countries that would allow them to send migrants that they apprehend at their borders to these countries.117 The migration deals with Tunisia, Egypt, and Rwanda have each been mired in controversy and allegations of human rights abuses.118 In July 2024, the United Kingdom’s new prime minister, Keir Starmer, ended the agreement with Rwanda as his first major policy action.119

The Role U.S. Leadership Played in Advancing the LA Declaration

In many ways, the LA Declaration is emblematic of how the forty-sixth U.S. president tackles major foreign policy challenges: he consistently brings leaders together, despite differences, and builds coalitions. It is this approach that unified the North Atlantic Treaty Organization behind Ukraine in 2022 after Russia’s invasion, for example, and he has also worked to bring key players in Asia together, despite differences, to counter China.120

The LA Declaration is emblematic of how the forty-sixth U.S. president tackles major foreign policy challenges.

Biden had established strong ties with Latin America over the course of his career. He traveled there sixteen times as vice president and even more as a U.S. senator and chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. In 2016, as vice president, Biden gave a major public speech on Latin America, where he emphasized the importance of partnership. “It’s not about what we can do for you,” he stated, “it’s about what we can do with you” (emphasis added).121 In May 2024, Sullivan reflected on Biden’s 2016 speech and how it represents the president’s approach to foreign policy in Latin America.

“That’s been our key focus since day one of the Biden-Harris Administration: leveraging the power of partnership. Not only to build a strong business case for the Americas . . . but to build a strong region writ large. A region that can lead the world. A region that can overcome any challenge.”122

The LA Declaration also demonstrates that when the United States asserts leadership on these issues, the world pays attention. This was true after World War II when the United States led the ad hoc committee to draft the 1951 Refugee Convention.123 It was also true in 2016 when Obama convened the Refugee Summit at the United Nations General Assembly in response to the Syrian refugee crisis, catalyzing the development of the Global Compacts on Refugees and Migration. U.S. leaders, Republican and Democrat alike, should do more to harness the influence they have to shape global refugee and migration response. It is a privilege and responsibility.

Conclusion

The migration response of the United States or any country cannot start and end at its borders. Thoughtful foreign policy on this issue is critical, especially at a moment when the world is facing historic levels of displacement.

The LA Declaration has introduced a simple, three-pronged approach for governments to engage and partner on this issue. It is starting to yield results in the Western Hemisphere. In the last two years, the creativity and risk-taking it has ignited is perhaps its greatest achievement. With elections across the region this year, including the United States, the strength and lasting impact of the LA Declaration will depend largely on new leaders stepping forward, trying new things, and working together.

About the Author

Katie Tobin is a nonresident scholar in the American Statecraft Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. She also serves as a Pritzker fellow at the University of Chicago’s Institute of Politics and is a frequent press contributor. From 2021 to 2024, Tobin served as a deputy assistant to the president and a coordinator for the Los Angeles Declaration in the White House National Security Council.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Chris Chivvis and Beatrix Geaghan-Breiner from Carnegie’s American Statecraft Program for their contributions to this paper. I would also like to thank the regional experts who reviewed and provided meaningful feedback on the piece: Dan Restrepo, Ryan Berg, and Juan Gonzalez. Finally, I am grateful to the many dedicated individuals inside and outside government and across the Americas who were the architects and visionaries behind the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection and who continue to carry its torch in the name of regional migration cooperation.

Notes

1 “Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection,” White House, June 10, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/10/los-angeles-declaration-on-migration-and-protection/.

2 “It looks very different if you look at migration across the hemisphere rather than standing on the U.S.-Mexico border, which is what the United States has tried to do for the last 30 years,” said Dan Restrepo, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress who served as an adviser to Obama on Latin America. See Miriam Jordan, “The U.S. and Latin American Countries Will Commit to Receive More Migrants,” New York Times, June 9, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/09/world/americas/summit-migrants-latin-america.html.

3 In June 2022, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) reported 6.13 million Venezuelan refugees and migrants in the world. See R4V Latin America and the Caribbean, Venezuela Refugee and Migrants in the Region – June 2022, August 10, 2022, https://www.r4v.info/en/document/r4v-latin-america-and-caribbean-venezuelan-refugees-and-migrants-region-june-2022. As of June 2024, UNHCR reports 7.77 million Venezuelans, See R4V Latin America and the Caribbean, Venezuela Refugees and Migrants in the Region, June 3, 2024, https://www.r4v.info/en/document/r4v-latin-america-and-caribbean-venezuelan-refugees-and-migrants-region-may-2024. In June 2023, UNHCR reported 6.48 million Ukrainians and 4.98 million Syrians. These figures do not include internally displaced persons (IDPs). See Ukraine Situation Flash Update #70, UNHCR, June 14, 2024, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/109336; Situation Syria Regional Refugee Response, UNHCR, https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria.

4 In 2020, Latin America and the Caribbean’s GDP dropped by 7 percent—the worst of any region tracked by the International Monetary Fund. See “Why Latin America’s Economy Has Been So Badly Hurt by COVID-19,” Economist, May 13, 2021, https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2021/05/13/why-latin-americas-economy-has-been-so-badly-hurt-by-covid-19.

5 Venezuela only represents part of the displacement challenge in the Americas. With large-scale outflows from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, Central America, and other pockets of the region, the Americas represent only 8 percent of the total global population but over 20 percent of the world’s displaced population. UNHCR, “The Americas,” https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/regions/americas; European Commission, European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, “Forced Displacement,” https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/what/humanitarian-aid/forced-displacement_en.

6 In May 2024, Guatemala’s new president Bernardo Arévalo hosted the third LA Declaration ministerial in two years. Secretary of State Antony Blinken represented the United States. Beth Carter, “Guatemala Hosts Third Los Angeles Declaration Ministerial With Blinken to Tackle Migration Issues, US Commits $578M in Aid,” Hoodline, May 8, 2024, https://hoodline.com/2024/05/guatemala-hosts-third-los-angeles-declaration-ministerial-with-blinken-to-tackle-migration-issues-u-s-commits-578m-in-aid/.

7 “G7 Apulia Leaders’ Communique,” White House, June 14, 2024, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/06/14/g7-leaders-statement-8/.

8 According to the UNHCR, over 117 million people were displaced globally at the end of 2023, the highest number ever recorded. See United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2023, June 13, 2024, https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/global-trends-report-2023.pdf.

9 “A Conversation With Amy Pope,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 11, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/event/conversation-amy-pope.

10 “Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, adopted by the Colloquium on the International Protection of Refugees in Central America, Mexico and Panama, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 22 November 1984,” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/cartagena-declaration-refugees-adopted-colloquium-international-protection-refugees-central.

11 Neither the United States nor Canada signed onto the Cartagena Declaration. However, both countries have been active observers and donors under the framework.

12 Luisa Feline Freier and Nicolas Parent, “A South American Migration Crisis: Venezuelan Outflows Tests Neighbors Hospitality,” Migration Policy Institute, Jule 18, 2018, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/south-american-migration-crisis-venezuelan-outflows-test-neighbors-hospitality.

13 Amelia Cheatham and Diana Roy, “Venezuela: The Rise and Fall of a Petrostate,” Council on Foreign Relations, December 22, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/venezuela-crisis; and Figure 1 in Alex Nowrasteh, “Venezuela: The Biggest Humanitarian Crisis You Haven’t Heard of,” Cato Institute, July 20, 2018, https://www.cato.org/blog/venezuela-biggest-humanitarian-crisis-you-havent-heard.

14 Amelia Cheatham and Diana Roy, “Venezuela: The Rise and Fall of a Petrostate”; and Figure 1 in Alex Nowrasteh, “Venezuela: Tthe Biggest Humanitarian Crisis You Haven’t Heard of.”

15 “Venezuela,” in Freedom in the World 2019, Freedom House, 2019, https://freedomhouse.org/country/venezuela/freedom-world/2019.

16 “Number of Refugees, Migrants From Venezuela Reaches 3 Million,” International Organization for Migration, November 9, 2018, https://www.iom.int/news/number-refugees-migrants-venezuela-reaches-3-million.

17 “Refugees and Migrants From Venezuela,” R4V Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants From Venezuela,” https://www.r4v.info/en/refugeeandmigrants.

18 In 2019, the Brookings Institution issued a report noting the stark contrast in how the Syrian and Venezuelan refugee crises were funded. “In response to the Syrian crisis, for example, the international community mobilized large capital inflows, spending a cumulative $7.4 billion on refugee response efforts in the first four years. Funding for the Venezuelan crisis has not kept pace; four years into the crisis, the international community has spent just $580 million. On a per capita basis, this translates into $1,500 per Syrian refugee and $125 per Venezuelan refugee.” Dany Bahar and Meagan Dooley, “Venezuela Refugee Crisis to Become Largest and Most Underfunded in Modern History,” Brookings Institute, December 9, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/venezuela-refugee-crisis-to-become-the-largest-and-most-underfunded-in-modern-history/.

19 Like those in other world regions, South American governments moved quickly in the early months of the coronavirus pandemic to introduce strict border closures, entry bans, and mandatory lockdowns. Many of these policies, which aimed to prevent the spread of the disease by stemming mobility, remained in place through much of 2020 and 2021. These measures had far-reaching consequences on migrant and refugee populations, including the millions of Venezuelans displaced in the region. Luisa Feline Freier, Andrea Kvietok, and Leon Lucar Oba, “Converging Crises: The Impacts of COVID-19 on Migration in South America,” Migration Policy Institute, March 2024, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/mpi_covid-mobility-south-america_final.pdf.

20 “Refugees and Migrants From Venezuela,” R4V Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants From Venezuela,” https://www.r4v.info/en/refugeeandmigrants.

21 Worldwide, gross domestic product contracted by 3 percent in 2020, but in Latin America and the Caribbean, GDP dropped by 7 percent—the worst of any region tracked by the International Monetary Fund. See “Why Latin America’s Economy Has Been So Badly Hurt By Covid-19,” Economist.

22 In contrast to the other top host countries in South America, Chile’s economy rebounded quickly from the pandemic. Secondary migration movements from Chile after the pandemic were likely due to new, restrictive immigration policies that were instituted here. In April 20, 2021, the Sebastián Piñera administration enacted Chile’s first new migration law in almost four decades. The law expands government authorization to deport migrants and limit their protections. It curtails movement for migrants without legal status. It offers the possibility to regularize migration status but only to those who entered Chile before March 18, 2020, when the government first closed its borders due to COVID-19. “Chile, International Migration Outlook 2023,” OECD, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/bcd9b377-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/bcd9b377-en#:~:text=On%2012%20February%202022%2C%20a,resident%20status%20has%20been%20abolished.

23 Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (known as AMLO) took an austere approach to the pandemic and, unlike many other leaders, was reluctant to introduce robust stimulus packages or increase public spending. Mexico actually spent the least among major Latin American economies on pandemic stimulus efforts. Some say this approach brought about a quicker recovery because Mexico was able to maintain a healthier budget and more stable macroeconomic situation. Others argue that AMLO’s response to the pandemic was insufficient and that Mexico had a slow recovery. See Daniel Chiquiar, “Mexico Recovering From Pandemic Slowdown; Structural Issues Persist,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, March 10, 2023, https://www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2023/swe2301; and Jason Marczak and Cristina Guevara, “COVID-19 Recovery in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Partnership Strategy for the Biden Administration,” Atlantic Council, March 16, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/covid-19-recovery-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-a-partnership-strategy-for-the-biden-administration/.

24 Joe Hernandez and Carrie Kahn, “Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse Assassinated, Shocking the Unstable Nation,” National Public Radio, July 7, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/07/07/1013670543/haitian-president-jovenel-moise-was-assassinated-at-home-according-to-the-acting.

25 “Latin America Wrestles With a New Crime Wave,” International Crisis Group, May 12, 2023, https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-caribbean/latin-america-wrestles-new-crime-wave.

26 Will Freeman, “The Predatory Economy Thriving in Panama’s Darien Gap,” Americas Quarterly, July 27, 2023, https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/the-predatory-economy-thriving-in-panamas-darien-gap/; Miriam Jordan, “Smuggling Migrants at the Border Now a Billion-Dollar Business,” New York Times, July 25, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/25/us/migrant-smuggling-evolution.html; “Latin America’s Most Powerful New Gang Built a Human-Trafficking Empire,” The Economist, November 16, 2023, https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2023/11/16/latin-americas-most-powerful-new-gang-built-a-human-trafficking-empire.

27 Julie Turkewitz, “‘A Ticket to Disney’? Politicians Charge Millions to Send Migrants to the U.S.,” New York Times, September 14, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/14/world/americas/migrant-business-darien-gap.html.

28 Daniel F. Runde and Thomas Bryja, “Mind the Darien Gap, Migration Bottleneck of the Americas,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 16, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/mind-darien-gap-migration-bottleneck-americas.

29 Adam Isacson, “Weekly U.S.-Mexico Border Update: A Large Group of Haitian Migrants in Del Rio, Texas Faces Horses, Hunger, Expulsion Flights, &—for Some—‘Notices to Report’ in the U.S.,” Washington Office on Latin America, September 27, 2021, https://www.wola.org/2021/09/weekly-border-update-large-group-haitian-migrants-del-rio-texas-faces-horses-hunger-expulsion-flights-some-notices-report-in-us/.

30 The Center for a New American Security conducted an analysis on the impact the Del Rio event had on regional migration policy, noting that, “The scale and scope of the Haitian migration event—one of several that has emerged in the hemisphere in recent years and impacted its countries in different ways—demonstrated the need for a coordinated response. These events supersede the ability of individual states and, potentially, the abilities of bilateral agreements, to adequately respond to complex needs.” See Cristobal Ramon, “Beyond the L.A. Declaration on Migration and Development,” Center for a New American Security, August 31, 2022, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/beyond-the-l-a-declaration-on-migration-and-development.

31 This would build on efforts already underway in Colombia. In 2021, the World Bank approved an $800 loan for Colombia under the Global Concessional Financing Facility (GCFF), with substantial U.S. backing, to support the country in integrating over 2 million Venezuelans in the country. Global Concessional Financing Facility, “Program to Support Policy Reforms for the Social and Economic Inclusion of the Venezuelan Migrant Population in Colombia,” https://www.globalcff.org/gcff_project_cpt/program-to-support-policy-reforms-for-the-social-and-economic-inclusion-of-the-venezuelan-migrant-population-in-colombia/.