In 2018, the United Nations (UN) reported that social media had played a significant role in the 2017 Rohingya genocide in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. The UN also identified Facebook as a “useful instrument” for spreading hate speech in the country. Despite subsequent intense international scrutiny of online platforms, the UN special advisor on the prevention of genocide stated in October 2022 that hate speech and incitement to genocidal violence on social media were “fueling the normalization of extreme violence” in Ethiopia. Two months later, a $1.6 billion lawsuit in Kenya’s High Court accused Facebook’s parent company Meta of amplifying hate speech and incitement to violence on Facebook in relation to Ethiopia’s 2020–2022 Tigray War. Meanwhile, pro-military actors in post-coup Myanmar continue to weaponize new social media platforms such as Telegram to target and silence dissent.

Different forms of online violence—such as radicalization, incitement, coordination, and repression—in the Tigray conflict and post-coup Myanmar demonstrate both the progress and the limitations of tech platforms’ atrocity-prevention efforts since the turning point resulting from the Rohingya genocide. Since 2017, social media companies have made genuine progress in atrocity prevention practices; nevertheless, these companies—along with regulatory bodies and civil society—are still failing to comprehensively address and prevent potential harm associated with their platforms.

This piece first presents an overview of online hate speech and its links to offline violence through chronological case studies of the Rohingya genocide, the Tigray War in Ethiopia, and post-coup violence in Myanmar, followed by a typology of potential pathways between social media and offline harm. It then takes Facebook and Telegram as examples to identify progress as well as persistent gaps in both content moderation and platforms’ underlying algorithms. Finally, it offers solutions in moderation, regulation, and remediation, while recognizing the importance of accompanying offline conflict prevention measures.

An Introduction to Facebook and Telegram

This piece focuses on two digital platforms: Facebook and Telegram. Facebook is a critical case study because of its status as the most-used social media platform in the world, with 2.9 million monthly active users. Facebook has an enormous impact on civic discourse and is one of the most pervasive and powerful sources of information and networks, both globally and in Ethiopia and Myanmar. Facebook is also an example of a platform that has received extensive international criticism for its role in mass atrocities and that has documented specific operational changes in response.

At the same time, smaller platforms such as Telegram have also proven to have an outsize impact on hate speech and incitement, including in Myanmar. With 700 million monthly active users, Telegram is a hybrid between a social media platform and a messaging service, and its hands-off approach to free speech has attracted pro-democracy activists and violent extremists alike. Users can establish public or private channels where anyone can like, share, or comment, as well as private groups with up to 200,000 members. This piece focuses on the platform’s public channels, which operate similarly to traditional broadcast media such as radio except for their greater opportunities for engagement between users, wider potential for multimedia content, and lower barriers to accessing and publicly disseminating information. Many similar digital platforms with smaller user bases have also demonstrated their mobilizing potential with even looser terms of service and therefore demonstrate the need for industry- rather than company-specific regulation.

A Timeline of Digital Platforms’ Crisis Response in Myanmar and Ethiopia

2017: Myanmar

In Myanmar, Facebook was famously implicated in the genocide against the Rohingya ethnic minority. In 2017, Myanmar’s army, also known as the Tatmadaw, carried out a series of “clearance operations” in Rakhine state that unlawfully killed thousands of Rohingya, displaced more than 700,000 people, deliberately burned entire villages, and committed widespread sexual violence and torture.

Prior to the height of the violence in 2017, Facebook had become an epicenter of virulent anti-Rohingya content. Users associated with the Tatmadaw and radical Buddhist nationalist groups drew on long-standing historical narratives to spread disinformation and hate speech dehumanizing the Rohingya and calling for their elimination. Hundreds of military personnel, often under fake accounts or posing as entertainment pages, intentionally flooded Facebook, Twitter, and other online and offline news sources with anti-Rohingya content.

Meta faced several challenges in detecting offending posts in Myanmar. In early 2015, only two people reviewing problematic content at Facebook spoke Burmese, despite Myanmar’s 18 million active Facebook users, most of whom posted in Burmese or other local languages. Moreover, Myanmar was one of the largest online communities where many posters did not use Unicode, the encoding scheme used in most countries to represent languages and characters. Instead, many users relied on a local alternative called Zawgyi—but content posted using Zawgyi is not readable to Unicode users and vice versa. Because Facebook’s Burmese-to-English translation tool for content moderation relied on the Burmese Unicode script and not Zawgyi, it often provided serious mistranslations of Burmese content.

In 2018, the UN’s fact-finding mission in Myanmar reported that the role of social media in Tatmadaw violence was significant and that Facebook specifically was a “useful instrument” for spreading hate speech “in a context where . . . Facebook is the Internet,” largely because of the platform’s Free Basics service, through which the app was preloaded onto virtually every smartphone sold in the country from 2013 to 2017 and incurred no data charges. In this way, Facebook became a widely available and free way to communicate and access the internet in a country undergoing a rapid digital transition. The relatively unfettered proliferation of hateful messages on a platform that dominated the online information space may have created a permissive environment for violence, and the participation of Rakhine men alongside the Tatmadaw in attacks against Rohingya communities reflects the potential of online messaging for offline incitement.

International attention to social media’s role in the Rohingya genocide created a turning point in platforms’ approach to their use in mass atrocities. Following several high-profile reports on the use of Facebook in the genocide, in 2018, Facebook itself conducted an independent human rights assessment, which concluded that the company was not doing enough to prevent the platform’s use to foment division and incite offline violence. Following the findings, Meta took measures to improve its human rights–monitoring and atrocity-prevention capabilities. In Myanmar specifically, Facebook removed hundreds of pages and accounts associated with Myanmar’s military, developed font converters to support the country’s transition to Unicode, and built out manual and automated hate speech detection capabilities, including in local languages.

2020: Ethiopia

Online violence has affected regions beyond Myanmar. Hate speech has proliferated in Ethiopian and Ethiopian diaspora online spaces since the 2020 outbreak of the Tigray War between the Ethiopian government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), and it has come predominantly from the government and its supporters. Posts on Facebook and Twitter calling for violence against specific ethnic groups and designating people and communities as “terrorists,” “killers,” “cancer,” and “weeds” have gone viral. In a post shared nearly 1,400 times, pro-government activist Dejene Assefa stated there was still time to cut the necks of the “traitors” and sing victory songs on their graves. Even posts that were eventually taken down had often remained visible for weeks beforehand. Individuals and entire communities have suffered death threats and physical violence after social media users named or posted photos of them. For instance, one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit brought against Meta in the Kenyan High Court is the son of a man who was murdered after widely shared Facebook posts accused him of being associated with the TPLF.

By October 2020, Meta invested in collaborations with independent Ethiopian fact-checking organizations, employed more native speakers of Amharic and Oromo, developed AI-assisted hate speech detection and removal in those languages, and limited the spread of content from repeat policy-violators. However, the next year, a leak by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen revealed that as of December 2020, the company did not have enough employees with local language competency to manually monitor content regarding the situation in Ethiopia, and that difficulties with Facebook’s automated “classifiers”—the systems it relies on for hate speech detection in Oromo and Amharic—had left the company “largely blind to problems on [its] site.” In March 2021, Facebook shared an internal report stating that armed groups in Ethiopia were using the platform to incite violence against ethnic minorities and warned that “current mitigation strategies are not enough.”

In response to the leak, Meta increased its atrocity-prevention efforts in Ethiopia—but the efforts were still insufficient. In November 2021, the company released an update describing its advances in automated and manual hate speech detection, its integration of civil society feedback, and its media literacy billboard campaign in the Ethiopian capital. Yet by late 2021, Meta could monitor content in only four of the eighty-five languages spoken in Ethiopia, potentially leaving up to 25 percent of the population uncovered. As of late 2022, Meta had hired only twenty-five content moderators in the country. Even when hateful content was flagged through Facebook’s own reporting tools, Meta still did not consistently remove it. In June 2022, the human rights organization Global Witness conducted a test, submitting for publication twelve advertisements containing especially egregious examples of hate speech that had previously been removed from Facebook as violations of community standards. Facebook approved all twelve.

In December 2022, the lawsuit against Meta was brought in Kenya’s High Court, accusing the company of amplifying hate speech and incitement to violence in Tigray on Facebook. The case alleges that Facebook has not hired enough content moderators and that the algorithm prioritizes content—even hateful content—that spurs engagement. It calls for greater investment from Meta in content moderation in the Global South, especially in conflict-affected countries, as well as better pay and working conditions for moderators focused on these regions and approximately $1.6 billion in restitution for victims of hate and violence incited on Facebook. In April 2023, the Kenyan court granted the petitioners leave to serve Meta in California, and in May, dozens of leading human rights and tech accountability groups signed an open letter to Facebook in support of the plaintiffs.

2021: Myanmar Again, Post-Coup

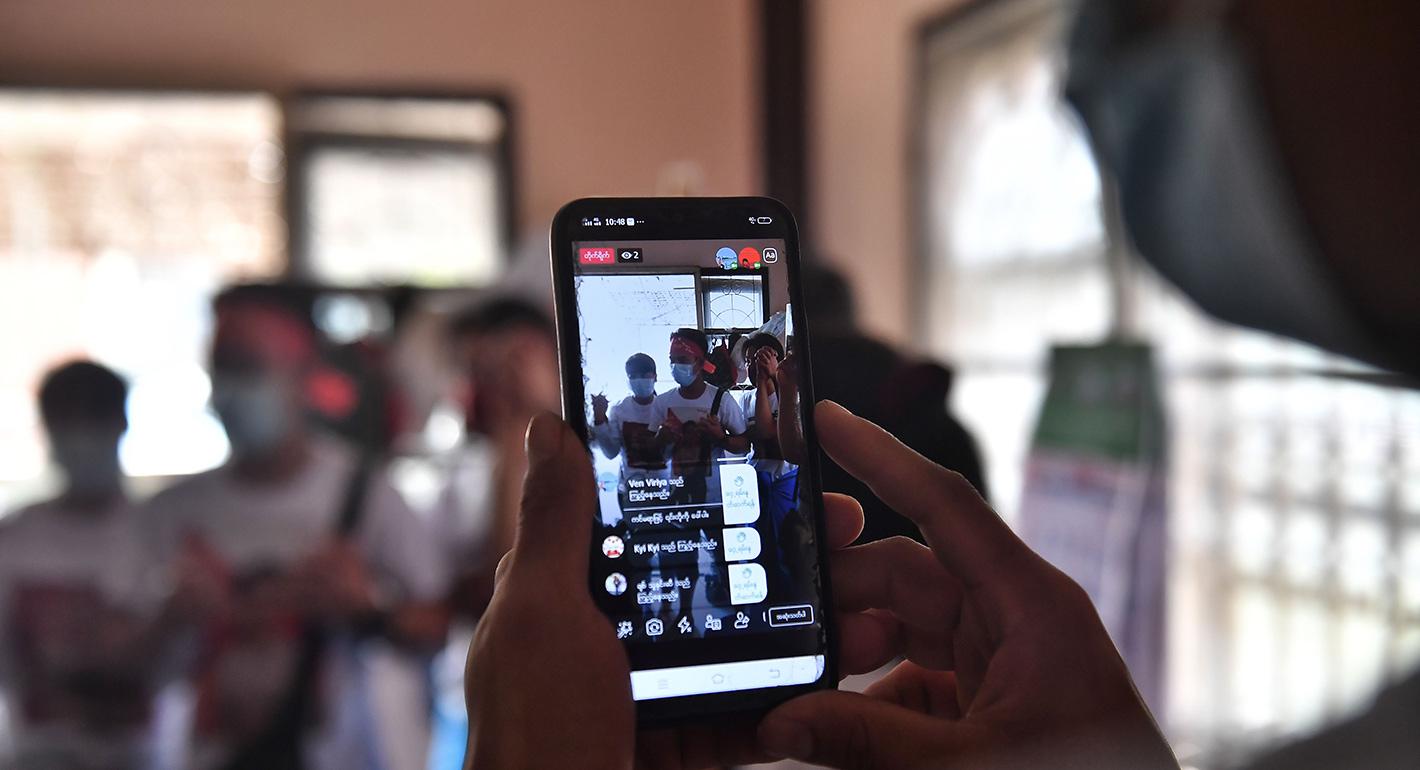

Meanwhile, the role of social media in conflict in Myanmar has changed drastically over the past two years. In February 2021, the Tatmadaw executed a military coup and subsequently unleashed an extreme campaign of violence resulting in nearly 3,000 verified deaths, over 17,500 arrests, and 1,477,000 people newly displaced since the coup. In this post-coup landscape, the role of social media platforms in mass atrocities in Myanmar has largely shifted from radicalization and incitement of spontaneous communal violence to high-specificity coordination and targeting.

In Myanmar, social media platforms have regularly been weaponized to target and silence dissent. Pro-military users of several Telegram messaging groups regularly urge military authorities to take action against pro-democracy activists, including through imprisonment, property seizure, revocation of citizenship documentation, and execution. For instance, the Han Nyein Oo Telegram channel, which had 73,238 subscribers in August 2022, regularly posts Facebook profiles and personal details of alleged resistance supporters. On several occasions, individuals whose information and locations were shared in these messaging groups have been arrested shortly thereafter. Similarly, thousands of social media posts—more than a fivefold increase from immediately post-coup to the end of 2022—have abused and doxed Burmese women, often because of their active political roles in the resistance.

The shift in the use of social media platforms reflects the more targeted nature of online violence. While Facebook has removed active, pro-military propagandists such as Han Nyein Oo, Kyaw Swar, and Thazin Oo, these notorious users have migrated to other services such as Telegram, Viber, and VKontakte (VK) to surveil people in digital spaces and help the junta hunt down perceived political enemies, including activists, politicians, protesters, and members of resistance forces.

Telegram has emerged as a favorite platform for violent actors in Myanmar. UN experts have warned that since the coup, pro-junta actors have taken advantage of Telegram’s nonrestrictive approach to content moderation and have attracted tens of thousands of followers by posting violent and misogynistic content on the platform. Though Telegram has blocked at least thirteen pro–Burmese military accounts in response to criticism, at least one of the most offending channels was back online in March 2023, and the UN experts noted that pro-military actors likely will simply open new accounts to continue their campaign of harassment.

Some of this intense online abuse reflects a failure to adequately perform the content moderation promised by platforms’ terms of service. The majority of the violent and misogynistic posts analyzed by the NGO Myanmar Witness remained live on social media platforms for at least six weeks on Facebook, Telegram, and Twitter, despite their violation of community standards. Many also remained live even after Myanmar Witness reported them. A minority of posts also may have avoided detection through imagery or coded slang, such as by using a word that combined a derogatory term for Muslims alongside the word for “wife” to discredit Burmese women perceived to be sympathetic to the country’s Muslim population.

In other cases, the abuse demonstrates blind spots within platform rules themselves. Telegram is particularly notorious for its light-touch content moderation policy, which prohibits calls for violence but does not police closed groups or ban hateful or doxing posts that call for action implicitly rather than explicitly. Among the abusive posts Myanmar Witness analyzed on Telegram, 21 percent did not violate existing platform guidelines but nonetheless posed real threats of offline harm.

A Typology of Social Media in Conflict

Myanmar and Ethiopia are not alone; high-profile cases of offline violence implicating social media have also emerged in Sri Lanka and India, among other countries. This pattern speaks to tech companies’ broader capability to amplify hate speech and promote violence. Social media has particular power in this regard thanks to the scale and speed of the spread of information, as well as the capacity for curated access to hateful content and anonymity that can shield users from accountability.

In addition to proposed generalized effects such as the dilution of facts through an overabundance of data, at least four possible pathways to harm have emerged: radicalization and persuasion, which change people’s underlying attitudes; activation of people who already hold dangerous views and might subsequently act on them; information-sharing, coordination, direction, and incitement of people to action; and appropriation of platforms to surveil and repress users.

Social media users tend to form and distribute information within separate echo chambers of like-minded individuals, thereby polarizing populations toward more extreme positions. This can have direct links to conflict; for instance, those studying the Rohingya genocide have argued that the proliferation of hateful content online may have led users to normalize, accept, and even support anti-Rohingya violence. Even among those already holding dangerous views, participation in violent networks can lead to increased exposure to hateful content, which has demonstrated links to violent action offline. For instance, members of Ethiopian civil society have alleged that the surge of hateful online content led people to spontaneously attack perceived enemies, such as Tigrinya speakers, offline. Online networks can also become centers for directly coordinating offline action; for instance, Facebook and Telegram groups in both Myanmar and Ethiopia publicized the personal details of alleged enemies, who often subsequently became targets of death threats and violence by group members. Finally, certain entities—often, governments or state military forces—can exploit social media platforms’ collections of user data to surveil and repress dissent. For instance, Myanmar’s junta uses advanced surveillance technology on social media apps to gather critics’ location data for arrests, alongside a suite of other technological tools. Any attempt to address social media–assisted mass atrocities should consider all these potential harms and pathways to violence.

The Limits of Progress

While Meta has taken steps to address its role in mass atrocities, significant gaps remain on its platforms, as well as on the platforms of other companies such as Telegram. Between the 2017 campaign in Myanmar and the 2020–2022 conflict in Ethiopia, Meta has made notable changes to atrocity prevention–related company policy and procedures. High-level commitments to human rights are a clear area of improvement. International condemnation of the company’s role in mass atrocities in Myanmar pushed Meta to invest in human rights policies and expertise and issue regular reports on coordinated inauthentic behavior, community standards enforcement, and civil rights, though technology and human rights groups have criticized these reports for their continuing lack of transparency and comprehensiveness. Meta also regularly meets with civil society organizations—albeit to potentially limited effect—not only for local monitoring and moderation but also for consultation on high-level policy.

Beyond explicit human rights provisions, human rights groups have also pushed Meta to adjust its practical content moderation procedures to limit the spread of misinformation and hate speech. Over the past few years, the company has introduced and published technical interventions such as warning labels over misinformation, “counterspeech” systems to present alternative information alongside false or misleading content, “downranking” to reduce the visibility of potentially harmful content, automated hate speech detection and removal systems, and deplatforming of harmful accounts. Meta has also developed an internal system for monitoring the risks of violence, even if this system is not publicly available and its links to increased resource dedication are uncertain. Meta has also increased its capabilities for content moderation outside of the United States, particularly through increasing the number of native language speakers reviewing content, expanding lists of banned slurs, and improving efforts toward proactive automated hate speech detection.

Still, these efforts have not gone far enough. Evidence from Ethiopia, Myanmar, and elsewhere shows that online hate speech has continued to slip through the cracks. Social media companies have failed to meet their responsibilities as both moderators and curators of potentially harmful content—a deficiency underlined by their recent dwindling revenues and mass layoffs.

Platform as Moderator: Investing in Content Moderation

Content moderation remains imperfect—social media companies still face lag times and miss harmful posts. On its online Transparency Center, Facebook reports that among actioned content, it has consistently found and actioned over 97 percent before it was reported by users. However, the key here is “among actioned content.” In internal documents from 2021, researchers estimated that the company was removing less than 5 percent of all hate speech on Facebook. Much of this discrepancy can be ascribed to three gaps: capability, capacity, and commitment.

Facebook still lacks critical capabilities: its language competency is still insufficient, and it has not yet developed automated tools (like Ethiopia’s failed hate speech classifiers or mechanisms to detect and analyze text embedded in images and videos) to an adequate level. Moreover, some of its new tools, such as misinformation labels, may have only limited effect on users.

Facebook also lacks capacity, including non–English content moderation staff and resources. As of 2020, 84 percent of the company’s misinformation prevention efforts were directed toward the United States, leaving only 16 percent directed toward the rest of the world. These disparities are also replicated within countries themselves: one Ethiopian researcher interviewed by the BBC reported that posts written in languages other than Amharic are “less vulnerable to being reported and blocked.” Tech companies’ recent dwindling revenues and mass layoffs demonstrate that when companies face an increasing capacity gap, countries in the Global South are often considered low priority and are therefore most negatively affected. For instance, in January 2023, a third-party contractor shut down the Nairobi hub responsible for content moderation in Ethiopia and Kenya as Meta introduced widespread global layoffs amid reduced revenues. Even in the United States, Facebook has claimed that because of a lack of content moderators, it is relying more on automated systems and may choose not to review user-reported content deemed low risk.

Facebook’s inadequate commitment to content moderation is also an obstacle. Some local fact-checkers and civil society organizations have alleged that Meta has frequently ignored their requests for meetings or support and been reluctant to incorporate their advice—despite the fact that Meta originally initiated the partnerships. In response to the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, Facebook implemented its “break the glass” crisis response procedure, a series of algorithmic changes meant to contain, mute, and remove inciting and hateful content. However, the platform did not implement such a procedure for Ethiopia, even when it knew armed groups in the country were using its platform to incite violence.

If these three areas are gaps in Meta’s content moderation, Telegram takes those inadequacies to an extreme: the company’s small production team almost certainly lacks the capacity and the competency to moderate content from its rapidly growing global user base of over 700 million monthly active users—and it does not even try. The app explicitly presents itself as a free speech alternative to other platforms and consequently not only has very limited platform guidelines but also seems to neglect rules that do exist. Although the app bans explicit calls to violence and reportedly took down hundreds of calls to violence in the wake of the January 6 attack (which was largely organized over its platform), Telegram and many other fringe platforms are renowned for letting hateful content go largely unchecked.

Platform as Curator: Algorithms and Business Model

Though content moderation changes are vital, they do not address more fundamental concerns about how social media algorithms and business models incentivize and promote hateful content. Social media platforms can moderate user-generated content, but they also have the power to curate their users’ feeds through algorithms that determine what content users have access to and in what order they see it. While messaging services tend to sort content chronologically or thematically, other platforms use statistical algorithms to promote content to users demonstrating specific marketing profiles or behaviors. While social media companies are often notoriously cagey about their algorithms, these mechanisms are key to what users consume.

Telegram does not have targeted advertising or an algorithmic feed, but Facebook has been central to discussions of content curation. According to a 2022 Amnesty International report, Facebook’s content-shaping algorithms promote inflammatory, divisive, and harmful content because such content is more likely to maximize engagement and therefore advertising revenue. The report alleges that these algorithms actively amplified content that incited violence in the Rohingya genocide.

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg has contested these allegations of engagement maximization and argued that Facebook focuses on helping people have “meaningful social interactions.” To this end, the company’s president of global affairs, Nick Clegg, has announced certain algorithmic changes such as the demotion of political content and pages in favor of connections’ posts. Clegg also maintained that “it takes two to tango” and that Facebook’s algorithm simply reflects the personal choices of individual users, who also share harmful content on platforms without ranking algorithms and commit violent acts offline with no social media involvement at all.

Facebook’s arguments that its algorithm prioritizes users’ connections and relationships over corporate profits warrant scrutiny. For one, a Facebook spokesperson has said that the company has “no commercial or moral incentive to do anything other than give the maximum number of people as much of a positive experience as possible.” However, the spokesperson did not specify how Facebook defines “positive experience,” which could be interpreted to mean time spent on the platform. The idea that Facebook is a neutral actor and that humans are the real problem is equally dubious. Even if Facebook doesn’t create content, its platforming and amplification of harmful posts is a form of editorial oversight, as are its decisions on what content to promote. In her testimony, Haugen noted that a 2018 change in Facebook’s news algorithm led European political parties to report that they felt compelled to take more extreme positions so that their content would be prioritized on the platform. Moreover, in addition to content curation and distribution, Facebook may also encourage users to take actions like joining a radical group; Meta itself has published research on its operations in Germany demonstrating that 64 percent of people who joined an extremist Facebook Group did so because the platform recommended it.

The true impact of Meta’s algorithms is difficult to evaluate given the platform’s lack of transparency, and research in this area remains unsettled. Nevertheless, the commitment gap may be at play here, too. To preserve revenue—and potentially, to avoid facing retribution for moderation decisions that run afoul of political actors, as was the case in Uganda, which banned Facebook ahead of the January 2021 elections—changes to content moderation alone may only tweak at the edges while producers of hateful content continue to emerge and post faster than social media companies can remove them.

Solutions

Governments, civil society, and social media companies themselves must prioritize further atrocity-prevention measures on platforms like Facebook and Telegram. Social media companies must face full accountability for harm and close gaps in competency, capacity, and commitment. Ultimately, solutions fall into three categories: moderation, regulation, and remediation.

Moderation

Platforms must adequately fulfill their responsibilities as content moderators. Meta’s spotty record—and worse, Telegram’s explicitly hands-off approach to content moderation—is unacceptable when a company’s products are associated with violence. Content moderation in conflict-affected contexts needs more robust, consistent, accurate, and rapid procedures for flagging, downranking, and removal of harmful content and actors. It also needs better automated hate speech detection systems, as well as more systematic and powerful crisis prevention and response. To solve these problems, tech companies should commit to context-specific human rights due diligence and technical changes to address misinformation and hate speech, prioritizing contexts at high risk of violence. But greater human rights oversight, especially with increased data transparency, is equally necessary to adequately monitor content.

Both local specificity and additional resources are necessary to improve content moderation. Often, social media companies establish many potentially useful interventions—such as hate speech lexicons, automated detection, media literacy programs, internal content moderators, and local third-party fact-checkers who can monitor, flag, and remove harmful posts and accounts. But companies then fail to adequately resource them or do not know how to apply them in unfamiliar environments. First, contextually appropriate due diligence and conflict sensitivity must be guiding principles throughout the design, development, release, and maintenance of products and services. Second, social media companies should close the capacity gap and dedicate significant funding for their own or trusted local civil society programs to improve their platforms’ manual and automated hate speech detection systems in different languages. Different places present very different challenges in harm mitigation, and cutting across all content moderation recommendations is the need to invest in and meaningfully incorporate feedback from local partners.

Given limited resources, social media companies must concentrate resources toward contexts where there is greater risk of violence—especially because, in recent years, many tech corporations have been under mounting financial pressure. Currently, social media companies often make investments largely guided by market logic and profits, leading to underinvestment in contexts with relatively lower market presence, such as Ethiopia, where only 10 percent of the country uses Facebook. The company’s current internal tier system is not public or subject to external review, but, according to Haugen’s leaked documents, it does not demonstrate straightforward links to risk of harm. Tech companies should use both reliable external estimates (such as those of the Dartmouth and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum) and internal risk assessments (which companies like Meta already perform) to identify countries with elevated risk of violence and offer appropriate support. Important steps in this regard might include standardizing procedures for applying temporary break-the-glass-style crisis measures—such as upranking credible news sources, banning mass invites to groups, capping virality, and not recommending civil or political content or groups—in countries facing violence, as well as intensifying rapid-response capabilities in at-risk contexts. Finally, though they have recently suffered falling revenues, Meta and other very large social media companies still have ample resources that they could afford to shift to content moderation and atrocity prevention.

Any changes in human rights due diligence or procedures must be paired with stronger human rights oversight. The front line for oversight is company leadership. Company boards should include people with expertise and experience in human rights, particularly related to digital technologies. However, more robust oversight mechanisms lie outside of companies themselves, and greater data and algorithmic transparency and disaggregation are a central pillar of accountability. To its credit, Meta does issue quarterly reports on the enforcement of its community standards. However, platforms like Telegram do not, and even Meta’s metrics are not comprehensive and do not include measures to forecast or address risk of violence. Additionally, while social media companies conduct research on the potentially harmful impacts of their platforms, their findings and the data on which those findings are based are only shared internally, so external parties cannot evaluate the adequacy of their response.

Ethiopia provides an example of inadequate transparency. Despite Meta’s own awareness that armed groups in Ethiopia were using Facebook to incite violence against ethnic minorities, a lack of public transparency meant that external parties could not push the company to mount an adequate response. Even when Meta did report local improvements, such as developing its classifiers and hiring more moderators, the company did not announce specific changes or numbers of hires. Consequently, the nature, timeline, potential impact, and retrospective efficacy of these investments could not be independently assessed, including in relation to need. Companies should be transparent about the potential risks their users face and the platform’s specific response, and they should publish clear, disaggregated data, to the extent that doing so does not endanger user privacy or expose vulnerable communities to harm.

Regulation

Tech companies should not be treated as the sole authority on the extent and success of their own atrocity-prevention efforts, as they are driven by individual and financial incentives that can make them unreliable enforcers and evaluators. Further, because bad actors can migrate between platforms—as pro-government users did in Myanmar, switching their coordinated violence from Facebook to Telegram—it is necessary to enact mitigations that can reach beyond the practices of a single company.

At the same time, biased or overly broad censorship can threaten legitimate speech. For instance, internet shutdowns have been used as a weapon of war—including to allow armed forces to engage in brutal attacks in both Myanmar and Ethiopia—and social media platforms are often sites for the circulation of legitimate and critical information about impending attacks and escape routes. The Tatmadaw also has intensified searches and control of cell phones and imposed a strict and sweeping cyber crime law, and it surveils anti-military dissenters online, restricts access to the internet, and imposes internet shutdowns and censorship. To assist in determining what speech should be criminalized, the UN has provided the Rabat Plan of Action threshold test, which maintains that only incitement to discrimination, hostility, or violence that meets six proposed criteria should be criminalized.

To address these issues, states and multinational regulators should enact and enforce rules that hold social media companies accountable for risks and harm deriving from their platforms but that also protect legitimate speech. A commonly cited model to this end is the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which provide a core set of human rights standards for social media companies to voluntarily incorporate into risk mitigation. These standards include policy commitments, ongoing and proactive human rights due diligence and consultation, appropriate integration and response to findings, communication of human rights impacts, and remediation of harms. Though not binding, these principles should serve as a model that can be adopted by regulatory bodies with actual teeth.

Another such regulation is the European Union’s (EU) new Digital Services Act (DSA), which came into force in November 2022 and will be directly applicable across the EU in early 2024. Applying only to “very large online platform[s]” with more than 45 million monthly active users, the law does not order removal of specific forms of speech, but it does introduce a range of powerful oversight mechanisms. The DSA’s central tools are co-regulatory mechanisms, such as assessments, codes of conduct, and audits, which are attached to significant potential financial penalties of up to 6 percent of a company’s global revenue. Data transparency provisions provide another avenue for oversight. In addition to mandating regular risk-assessment reports, which are reviewed by an independent auditor whose findings are publicly disseminated, the law also mandates researcher access to data, including on how a platform’s algorithms work. Finally, oversight can come from users themselves, as the law also requires companies to allow users to flag illicit content.

The DSA is promising but may present new challenges. The prospect of significant financial penalties provides real incentive for companies to account for human rights due diligence. The law’s provisions on assessments, audits, and data transparency all introduce greater potential for oversight and evaluation of whether this due diligence is adequate. Although the EU has been at the forefront of tech regulation, its enforcement of policies has occasionally fallen short. Critics worry that the estimated 230 new employees hired to enforce the DSA and its twin, the Digital Markets Act, may be insufficient compared to the resources available from and the content produced by the companies the EU seeks to regulate. Moreover, proactive laws to hold social media companies accountable for content on their platforms may not be feasible everywhere, as demonstrated recently through the U.S. Supreme Court’s upholding of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. The EU should follow through by adequately resourcing and enforcing the DSA while other countries work toward these models.

Regulators might also consider more direct collaborations with social media platforms. In 2015, as Telegram was seeing growing use by the Islamic State for propaganda, recruitment, and coordination, Europol’s Internet Referral Unit began to flag extremist Islamic State content to Telegram but did not demand its removal or attempt to subpoena users’ data. As Telegram began to pay more attention to the reputational and legal risks posed by Islamic State content on its platform, the company began to action the content flagged by Europol. In 2019, Telegram and Europol conducted a joint operation that deleted 43,000 terrorist-related user accounts. Particularly for fringe platforms that may be unwilling or unable to conduct comprehensive content moderation, and for those that do not reach the DSA’s “very large online platform” threshold, co-regulation with law enforcement bodies on public content could provide a way for companies and regulators to tackle extremism jointly while avoiding regulatory action seen as overly invasive or punitive.

Remediation

Social media companies should publicly acknowledge and compensate victims of violence originating from their platforms. Several lawsuits are currently pending against Meta for its role in inciting violence, including the lawsuit regarding Facebook’s role in the Tigray conflict and at least three cases seeking remediation for the Rohingya people. Meta has an opportunity to set an industry precedent by establishing and strengthening transparent procedures and entities for both individual-level and group-level grievance mechanisms.

Platforms can also play a critical role in remediation proceedings where they are not the defendants, especially given the wealth of potential legal evidence on social media platforms. For instance, in continuing to cooperate in providing evidence for the International Court of Justice case against Myanmar for the Rohingya genocide, Meta should set a standard for compliance in any similar future cases. The company has recently made significant and welcome progress in this area, as its oversight board recommended that Meta “commit to preserving, and where appropriate, sharing with competent authorities evidence of atrocity crimes or grave human rights violations.” Meta has a real opportunity to set an industry precedent and create a powerful human rights evidence preservation mechanism, while balancing the sometimes competing interests of users’ rights to due process and privacy.

A Multidimensional Strategy

Ultimately, effective atrocity prevention requires a coherent, integrated plan across technical, sociopolitical, and legal domains. International organizations and civil society should support a variety of interconnected solutions for atrocity prevention. Social media is only one piece of the puzzle; offline strategies such as peacebuilding processes may be at least as impactful as social media monitoring in contexts like Myanmar, where the conflict is exceptionally widespread and intense. Violence should not be blamed solely on social media either—actors like the Tatmadaw, which has also conducted an organized offline campaign of violence, must be held accountable. Further, researchers at the International Crisis Group have suggested that risk management strategies on Ethiopian social media must work with and support healthy, independent traditional news media in the country.

But social media is increasingly central to civic discourse and has unique capabilities for the curation, distribution, and amplification of potentially harmful content. Unless social media companies are comprehensive in their removal of violent content and steadfast in their refusal to amplify hate for engagement, their platforms can grant bad actors unprecedented access to wide networks that are sympathetic by design.

Since the Rohingya genocide, Meta has demonstrated several genuine improvements that social media companies can make in atrocity prevention. Harm mitigation strategies—including strengthened human rights policies and expertise, engagement with local civil society organizations, and automated hate speech detection systems—are increasingly integrated into Facebook’s architecture. However, as users’ migration to Telegram shows, not all companies have taken similar steps, and many lack the funds, staff, tools, and will to take online violence seriously. And even Meta’s atrocity prevention efforts still suffer from significant gaps in capability, capacity, and commitment, particularly in the Global South and in conflict-affected contexts like Tigray.

To address remaining challenges, social media companies must integrate atrocity prevention and response throughout the life cycle of a potential crisis. Critically, platforms should work to prevent future violence by developing more accurate and robust systems for detecting and removing harmful content and actors. Should a crisis still arise, companies must be ready to mitigate the effects with a more systematic and powerful crisis response to limit its impact and spread. Finally, platforms should address past wrongs through remediation processes for victims.

These essential protections cannot rely on goodwill alone—they must be enforceable. Given the potentially devastating offline effects of digital hate speech and incitement to violence, everyone is better served by platforms that are subject to genuine accountability. Transparency, oversight, and regulations with teeth are critical to ensuring that social media companies uphold their duty of care to ensure that their platforms are not used for violence.