Preface

China Local/Global

China has become a global power, but there is too little debate about how this has happened and what it means. Many argue that China exports its developmental model and imposes it on other countries. But Chinese players also extend their influence by working through local actors and institutions while adapting and assimilating local and traditional forms, norms, and practices.

With a generous multiyear grant from the Ford Foundation, Carnegie has launched an innovative body of research on Chinese engagement strategies in seven regions of the world—Africa, Central Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and North Africa, the Pacific, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Through a mix of research and strategic convening, this project explores these complex dynamics, including the ways Chinese firms are adapting to local labor laws in Latin America, Chinese banks and funds are exploring traditional Islamic financial and credit products in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, and Chinese actors are helping local workers upgrade their skills in Central Asia. These adaptive Chinese strategies that accommodate and work within local realities are mostly ignored by Western policymakers in particular.

Ultimately, the project aims to significantly broaden understanding and debate about China’s role in the world and to generate innovative policy ideas. These could enable local players to better channel Chinese energies to support their societies and economies; provide lessons for Western engagement around the world, especially in developing countries; help China’s own policy community learn from the diversity of Chinese experience; and potentially reduce frictions.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

Vice President for Studies, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Summary

Commercial negotiations between Benin and China demonstrate how both sides navigate the dynamics of Africa-China business-to-business relationships. In Benin, Chinese and local Beninese officials engaged in drawn-out negotiations on a deal to construct a business center aimed at deepening business links between Chinese and Beninese merchants. Strategically located in Cotonou, Benin’s principal economic city, the center aims to promote investment and wholesale businesses by serving as a hub for China’s business-to-business relations not just in Benin but regionally in West Africa, especially in the large and growing neighboring market of Nigeria.

This paper relies on original research and fieldwork conducted in Benin from 2015 to 2021 and the author’s access to draft and final contracts from the negotiations, which allow for a side-by-side comparative textual analysis, as well as initial field interviews and follow-up interviews with key negotiators, Beninese businessmen, and former Beninese students in China. The paper shows how Chinese and Beninese authorities negotiated the establishment of the center and, above all, how Beninese authorities made Chinese negotiators adapt to local Beninese labor, construction, and legal norms and put pressure on their Chinese counterparts.

This strategy meant that negotiations took longer than usual to complete. China-Africa cooperation is often characterized by speedy negotiations, an approach that in some cases turns out to be harmful—since this can allow vague and unfair clauses to be featured in final contracts. The negotiations over the Chinese business center in Benin is a good example of how well-coordinated negotiators that take their time and work in coordination with various counterparts throughout the government can help facilitate better outcomes in terms of high-quality infrastructure and compliance with prevailing construction, labor, environmental, and business norms, while also preserving a good bilateral relationship with China.

Introduction

The study of business relationships between Chinese and African nonstate actors such as traders, merchants, and businesspeople has often focused on how Chinese firms and migrants import commodities and goods and compete with local African businesses. But there is a “parallel” set of Africa-China business relationships because, as Giles Mohan and Ben Lampert have argued, “just as many African governments have consciously turned to China as a potential partner for economic development and regime legitimacy, African citizens have increasingly reached out to China as a source of useful resources for personal and business progression.”1 The growing presence of Chinese goods in Africa is also attributable to African traders in China sourcing goods to be sold in African countries.

These business-to-business relationships, particularly in the West African country of Benin, are revealing. In the mid-2000s, Chinese and local bureaucrats in Benin negotiated the building of an economic and development center (locally referred as a business center) designed to foster economic ties and business connections between the two sides by offering an array of trade promotion, business development, and other related services. The center also aimed to help formalize business-to-business relationships between Benin and China, ties that had been largely informal or semi-formal. Strategically located in Cotonou, Benin’s principal economic hub near the city’s main harbor, the center was also meant to spur investment and wholesale business growth by serving Chinese businesses not just in Benin but regionally throughout West Africa, especially in the large and growing market of neighboring Nigeria.

This account investigates how Chinese and Beninese authorities negotiated the terms of the center’s opening and, above all, the ways Beninese authorities got Chinese negotiators to adapt to local Beninese labor, construction, and legal standards and norms.2 One result of this Beninese pressure on the Chinese negotiators was that the talks took longer than usual, allowing Beninese officials to ensure better regulatory enforcement. This analysis examines how such negotiations proceed in the real world, in a case where Africans not only had significant agency but leveraged it to considerable effect despite the asymmetrical nature of the relationship with China.

African business leaders are playing a key role in deepening economic ties between Benin and China and flourishing in the process, helping ensure that Chinese businesses are not the sole beneficiaries of proactive Chinese business engagement on the African continent. The case of this business center offers valuable lessons for African negotiators involved in business deals and related infrastructure negotiations with China.

Business-to-Business Ties Between China and West Africa

Trade and investment flows have been soaring between Africa and China in recent years. Since 2009, China has been Africa’s leading bilateral trade partner.3 And according to the latest global investment report from the United Nations (UN) Conference on Trade and Development, China was Africa’s fourth-largest investor (by foreign direct investment stock) behind the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and France in 2019,4 with Chinese investment increasing from $35 billion in 2015 to $44 billion in 2019.5

Yet these surges of formal trade volumes and investment flows do not truly capture the scope, intensity, and velocity of expanding economic ties between China and Africa. That is because governments and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which often receive a disproportionate share of media attention, are not the sole actors driving these trends. Indeed, the increasingly complex mosaic of actors in Africa-China business-to-business relations includes a large range of private Chinese and African actors, particularly small- and medium-sized enterprises. They operate in the formal organized economy but also in semi-formal or informal settings. The establishment of state-led business centers is meant in part to help facilitate and formalize these business relationships.

The Beninese economy, just like those of many other African countries, is characterized by a strong informal sector. According to the International Labour Organization, almost eight out of ten workers in sub-Saharan Africa were in “vulnerable forms of employment” as of 2014.6 Yet, as research from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) points out, informal economic activity tends to severely limit tax revenues for the developing countries that most need a stable tax base. This suggests that the governments of such countries have an incentive to better measure the scale of informal economic activity and learn how to shift production from the informal to the formal sector.7 Taken together, actors in the formal and informal economy are deepening Africa-China commercial relations. The roles of the governments involved alone simply do not explain this flurry of activity.

For example, beyond the large Chinese SOEs operating in Africa in various sectors, ranging from construction and power generation to agriculture and oil and gas extraction, there are several other key players. Chinese provincial SOEs are a factor too, though they do not have the same prerogatives and benefits as the large SOEs that fall under the purview of the central powers in Beijing, specifically the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission under the State Council. Yet these provincial firms increasingly win market share in several key African sectors, such as mining, pharmaceuticals, oil, and mobile phones.8 For these provincial corporations, internationalization has been a way to escape growing competition from the larger central SOEs in China’s domestic market, but expanding into new markets overseas also represents a way to grow their businesses. These state-run firms often operate in a largely autonomous way from any centrally directed planning dictated by Beijing.9

There are other important actors too. Besides central and provincial Chinese SOEs, large networks of private Chinese businesses are also operating in Africa via semi-formal or informal transnational networks. In West Africa, many of them have become established across the region, with larger numbers in countries like Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, and Senegal.10 These private Chinese firms are playing a growing role in China-Africa business relations. Regardless of the size of the companies involved, much analysis and commentary has tended to emphasize the role of these Chinese actors, including the private ones. Yet African private actors are also active in deepening a web of business relationships between their countries and China.

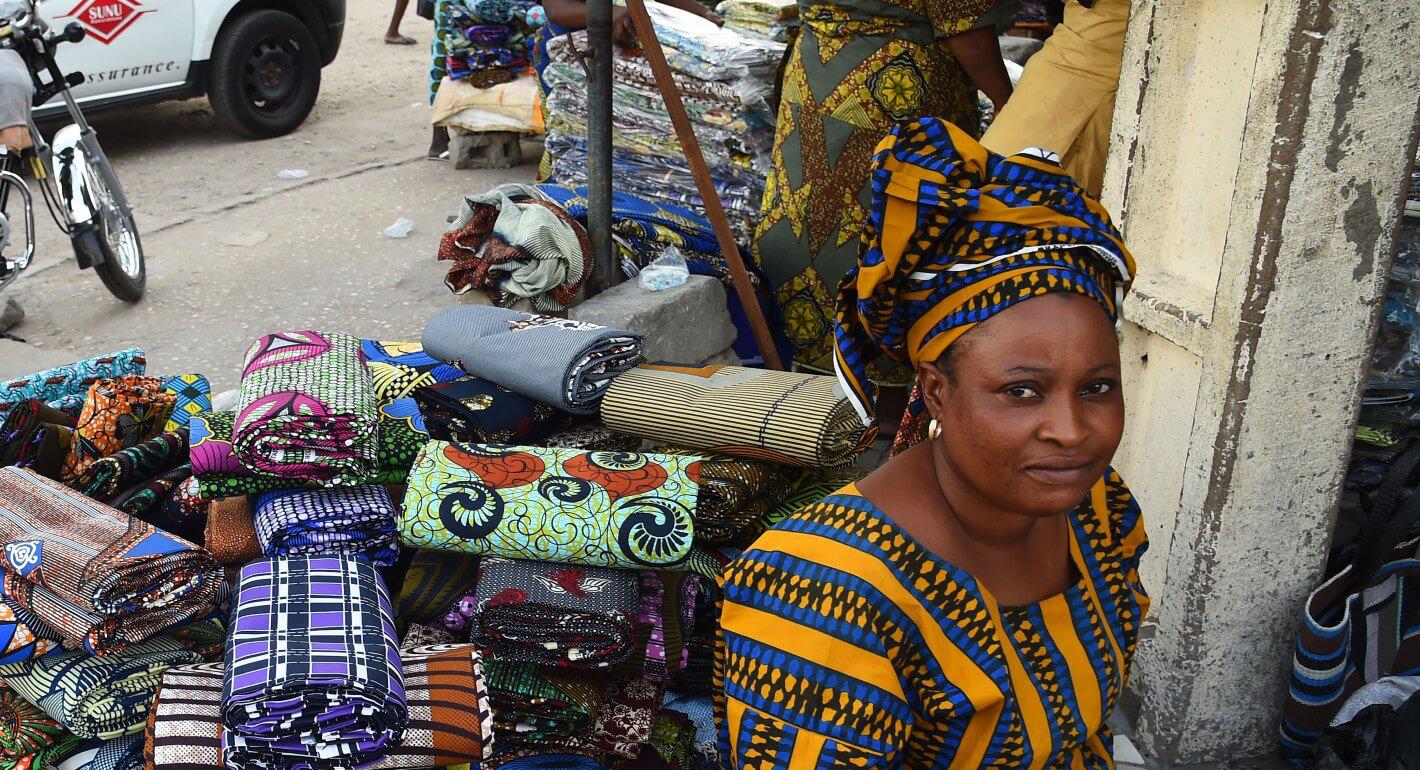

Chinese products (particularly textiles, furniture, and consumer goods) are ubiquitous in African markets, both in urban and rural areas. As China has become Africa’s top trade partner, the share of these products has now somewhat outstripped the market share of similar products made in Western countries.11

African business leaders are important contributors to the diffusion of Chinese goods in Africa. Acting as importers and resellers at various levels of relevant supply chains, they supply these consumer goods from several parts of mainland China and Hong Kong to be shipped through ports throughout West Africa like Cotonou (in Benin), Lomé (in Togo), Dakar (in Senegal), and Accra (in Ghana) among others.12 Their role is central in these increasingly dense business networks between China and Africa.

This phenomenon is grounded in historical links. In the 1960s and 1970s, some West African countries established diplomatic ties with the Communist-led People’s Republic of China (PRC) after gaining independence, leading to a flood of Chinese goods as Beijing’s overseas development cooperation programs took shape. These goods have long been sold in local markets, with the revenues generated recirculated for local development projects.13

But beyond African businesses, other African nonstate actors also have participated in these economic transactions, especially students. Since the 1970s and 1980s, when diplomatic relations between the PRC and several West African governments led to scholarships for African students to study in China, several African alumni of these programs have established small businesses to export Chinese goods to their home countries with the aim of offsetting local inflation.14

But the expansion of imports of Chinese goods into African economies has been especially impactful in Francophone Africa. This is in part due to fluctuations in the value of the Western African version of the franc of the Financial Community of Africa, also known as the CFA franc, a common regional currency once pegged to the French franc (and now tied to the euro). After the value of the CFA franc was cut in half in January 1994, Chinese consumer goods became more competitive as the price of imports of European consumer goods doubled in light of the currency devaluation.15 Growing numbers of both Chinese and African merchants (including new firms) made gains during this period by capitalizing on this trend, further deepening business connections between China and West Africa. These dynamics also helped African households by making a greater variety of Chinese-made goods available to African consumers. Ultimately, this trend accelerated the level of consumption seen in West Africa today.

Analysis of business-to-business ties between China and multiple West African nations show that African traders scour markets for deals on goods from China thanks to their accurate understanding of local markets back home. Mohan and Lampert note that “Ghanaian and Nigerian entrepreneurs are playing a much more direct role in encouraging the Chinese presence by sourcing not only consumer goods but also partners, workers, and capital goods from China.”16 Further, Chinese machinery and technology supports manufacturing production of some products in the two countries. Another cost-saving strategy is to recruit Chinese technicians to oversee the installation of equipment and training of local counterparts in operating, maintaining, and repairing such machinery. As researcher Mario Esteban has observed, some African actors “are actively bringing over Chinese workers . . . to increase productivity and provide higher quality goods and services.”17

To cite one example, Nigerian traders and business leaders established a Chinatown shopping center in the capital of Lagos as an entry point for Chinese migrants considering Nigeria as a business destination. According to Mohan and Lampert, the goal of this venture was “to attract Chinese entrepreneurs who would go on to establish factories in Lagos, thereby generating local employment and supporting economic development.”18 Chinese firms and business leaders have sought to make similar inroads in other countries in West Africa, including Benin.

The Evolution of Business Relationships Between Benin and China

Benin, a Francophone nation of 12.1 million people, reflects these intensified business dynamics between China and West Africa well.19 The country (previously named Dahomey) gained independence from France in 1960 before vacillating back and forth between diplomatic recognition of the PRC and the Republic of China (in Taiwan) until the early 1970s. Under president Mathieu Kérékou, who established a dictatorial regime with communist and socialist characteristics, Benin switched back to recognizing the PRC in 1972. He sought to learn from the Chinese experience and emulate elements of it at home.

This new, privileged relationship with China led to the opening of the Beninese market to Chinese products, such as Phoenix bikes and textiles.20 Chinese merchants established the Society of Textile Industries in Benin in the town of Lokossa in 1985 as well as the Benin Textile Company. Beninese merchants also traveled to China to buy other goods (including toys and fireworks) and bring them back to Benin.21 In 2000, under Kérékou, China supplanted France as Benin’s single largest trading partner. In 2004, Benin-China relations dramatically improved, widening China’s lead as the country’s top single trade partner, as China supplanted the European Union (see figure 1).22

Economic and Societal Drivers of Growing Commercial Ties

Aside from closer political ties, economic considerations also help explain these intensified trading patterns. The low costs for Chinese goods, despite high transaction costs including shipping fees and tariffs, made Chinese-made products attractive to Beninese merchants.23 China offered a variety of goods at different price ranges and speedy processing of visas for Beninese merchants, unlike Europe, where visas to do business in the Schengen Area became more difficult for Beninese (and other African) businesspeople to obtain.24 For this reason, China became the supplier of first resort for many Beninese businesses. Indeed, according to interviews with Beninese businesspeople and former students in China, the relative ease of doing business with China contributed to the expansion of the Beninese private sector by attracting more people to get involved in this economic activity.25

Beninese students also participated by taking advantage of easy-to-obtain student visas to learn the Chinese language and become translators between Beninese and Chinese merchants (including textile firms) in China and later back home in Benin. The presence of these local Beninese translators helped partially remove the linguistic barriers that often prevail between Chinese and overseas business partners, including in Africa. Beninese students have acted as liaisons between African and Chinese businesses since the early 1980s when Beninese (especially from the middle class) began to receive scholarships to study in China at scale.26

Students could play such roles in part because the Beninese embassy in Beijing, unlike the Chinese embassy in Benin, was largely composed of diplomats and technocrats covering politics with less of a focus on business relations.27 Consequently, many Beninese students were enlisted by local businesses in Benin to informally provide translation and business services such as identifying and scoping Chinese factories, facilitating local site visits, and conducting due diligence to inspect goods purchased from China. Beninese students offered these services in an array of Chinese cities, including Foshan, Guangzhou, Shantou, Shenzhen, Wenzhou, Xiamen, and Yiwu where scores of African merchants sought suppliers of everything from motorcycles, electronics, and construction materials to candy and toys. According to former students who were individually interviewed for this research, this concentration of Beninese students also built bridges between Chinese merchants and other West and Central African businesspeople, including ones from Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, and Togo.28

In the 1980s and 1990s, trade and business relations between China and Benin were mostly organized via two parallel tracks: official and formal governmental relations and informal business-to-business or business-to-consumer links. According to interviewees at the Beninese National Council of Employers (Conseil National du Patronat Beninois), Beninese firms not registered at the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Benin benefited the most from these growing relationships with China via direct sourcing of construction materials and other goods.29 These burgeoning relationships between the Beninese business sector and established Chinese enterprises grew further once China began to sponsor large government-to-government infrastructure projects in Cotonou, the economic capital of Benin. The visibility of these large construction projects (ministry buildings, conference centers, and so on) got Beninese businesses more interested in buying construction materials from Chinese suppliers.30

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, West Africa had seen this informal and semi-formal trade supplemented by the growing establishment of Chinese commercial hubs, including in Benin. Business centers initiated by local businesspeople also cropped up in the capitals of other West African countries (like Nigeria). These hubs helped African households and businesses facilitate much larger wholesale purchasing options for Chinese goods and enabled some African governments to better organize and formalize these business relationships, which had grown organically and separately from official economic and diplomatic relationships.

The Plans for a Major Commercial Hub in Cotonou

Benin is no exception. It, too, has seen new institutions established to better organize and formalize business-to-business relationships with China. The best example is the China-Benin Economic Development and Business Center (Centre Chinois de Développement Economique et Commercial au Benin), established in Cotonou’s main business district of Ganhi near the harbor in 2008. The center, also commonly referred to as the Chinese Business Center in Benin, was established as part of a formal joint partnership between the two countries.

While construction was not finished until 2008, an initial memorandum of understanding mentioning the intention to establish a Chinese commercial center in Benin was signed in Beijing a decade earlier in January 1998 during Kérékou’s presidency.31 The center’s main objective has been to promote economic and business cooperation among Chinese and Beninese actors. The center was built on a 9,700 square-meter plot of land and covers an area of 4,000 square meters. The construction costs, which amounted to $6.3 million, were covered by a hybrid funding package arranged by the Chinese government and Teams International, a provincial company from the city of Ningbo in Zhejiang Province. All told, 60 percent of this funding came in the form of grants, while the remaining 40 percent was funded by Teams International.32 The center was established via a build-operate-transfer (BOT) agreement, which includes a fifty-year lease from the Beninese government held by Teams International, after which the infrastructure is supposed to be transferred to Beninese control.33

It was originally representatives from the Chinese Embassy in Benin who suggested that the project would be a focal point for Beninese businesses interested in doing business with China.34 According to them, a business center would provide a central platform for Beninese and Chinese business representatives to engage in more trade and thus likely would eventually lead more informal businesses to formally register at the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Benin. But beyond being a one-stop commercial hub, the business center would also act as a nexus for a variety of trade facilitation and business development activities. It was designed to promote investment, imports, exports, and transit and franchise activities; organize exhibitions and international business fairs; store wholesale Chinese products; and advise Chinese enterprises interested in bidding on tenders for urban infrastructure projects, agricultural ventures, and services-related projects.

But while Chinese actors may have proposed the business center, that is not the end of the story. The negotiations took longer than expected because Beninese actors set expectations, made demands of their own, and drove a hard bargain to which the Chinese players then had to adapt. Fieldwork, interviews, and key internal documents provide important insights on the negotiations and how Beninese state actors, despite the asymmetrical nature of the country’s relationship with a more powerful China, were able to exert agency and convince the Chinese actors to adapt to local norms and business regulations.35

China’s Opening Offer

China-Africa cooperation is often characterized by the rapid negotiation, construction, and operationalization of an agreement. Critics argue that this speedy process has led to lower-quality infrastructure.36 By contrast, the Beninese negotiations on the Chinese business center in Cotonou demonstrate how much well-coordinated teams of bureaucrats from different ministries can achieve. This is especially true when they drive the negotiations by insisting on slowing things down; consulting with representatives from various corners of the government; and proposing solutions to attain high-quality infrastructure and ensure that local construction, labor, environmental, and business standards and norms are respected.

In April 2000, Chinese representatives from Ningbo came to Benin and established a project office for the construction of the center. The two sides began holding preliminary discussions. The Beninese side included representatives from the Directorate of Construction of the Ministry of Environment, Habitat and Urbanism (designated to spearhead the Beninese government’s team on urban construction projects); the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the Ministry of Planning and Development; the Ministry of Industry and Commerce; and the Ministry of Economy and Finance. The Chinese negotiators included the Chinese ambassador to Benin, the director of Ningbo’s Office of External Trade and Economic Cooperation, and representatives from Teams International.37 In March 2002, another delegation from Ningbo arrived in Benin and signed a memorandum with Benin’s Ministry of Industry and Commerce: the document designated the location of the future business center.38 In April 2004, Benin’s minister of industry and commerce visited Ningbo and signed a memorandum of understanding that launched the next stage of formal negotiations.39

Once formal talks on the business center began, the Chinese negotiators presented a draft BOT contract to the Beninese government in February 2006.40 But an in-depth look at this initial draft is revealing. A textual analysis of this initial draft (in French) shows how the Chinese negotiators’ initial position, which the Beninese side then sought to alter, included vague contractual clauses pertaining to the construction, operationalization, and transfer of the business center by the Chinese parties involved as well as terms involving preferential treatment and proposed tax exemptions.41

Construction Phase

Several clauses in the initial draft pertaining to the construction phase are worth noting. Some would have required Benin to take charge of certain “expenses” without specifying what these expenses would be.42 The Chinese party also requested that the wages of Beninese and Chinese workers on the project be “adjusted” without specifying the amount of such an adjustment.43 The proposed Chinese terms also required that preliminary feasibility and environmental impact studies be carried out by the Chinese side only, stating that a representative from a studies office (bureau d’études) based in China would be sent to do the impact study.44 The vague contract language also lacked timelines for the construction phase. For instance, one clause stipulated in broad terms that “the Chinese party will deliver feedback from the results of the technical studies” without mentioning when specifically this would happen.45 Similarly, the draft’s terms made no mention of safety protocols for local Beninese workers.

Center Operationalization and Transfer

In sections of the draft on the operationalization of the center, there were also several broad, vague clauses in the Chinese-proposed terms. The Chinese negotiators demanded that the Chinese business operators working in the business center be allowed to sell both wholesale and retail goods not just on the premises of the center itself but also in local Beninese markets.46 This demand contradicted the center’s initial aim of having Chinese businesses offer wholesale products that Beninese businesses could source in China and sell as retail goods in Benin and more broadly throughout West Africa.47 The center, according to these proposed clauses, would also allow Chinese parties to provide “other business services” without specifying which ones.48

Other clauses of this initial draft were similarly one-sided. The draft proposed that the Beninese parties involved would not be allowed to take “any discriminatory measures against the center,” without specifying the meaning of this clause, yet its terms seemed to offer far more wiggle room when it stated that the Chinese operators would merely “do their best” to offer jobs to Beninese locals without providing details on how this would be done.49

The Chinese negotiating parties also made specific requests for exceptionality. One paragraph demanded that “the Beninese party will not authorize any other Chinese party, or country from the (West African) subregion to build a similar center in the city of Cotonou for thirty years from the start of the operationalization of the center.”50 The inclusion of such a problematic clause highlights how the Chinese negotiators sought to stifle competition from other foreign countries and other Chinese actors alike. Such exceptionality clauses reflect the way that Chinese provincial companies try to compete with other firms, including other Chinese companies,51 by securing a privileged, exclusive commercial presence.

Just as with the terms on the construction and operationalization of the center, the clauses related to the eventual transfer of the project back to Beninese control called for Benin to be responsible for all related charges and expenses including lawyers’ fees and other costs.52

Preferential Treatment and Tax Exemptions

The draft contract also included several Chinese-proposed clauses involving bids for preferential treatment. For instance, one provision sought to ensure that land would be furnished in a suburb of Cotonou called Gbodje to build storage units for Chinese firms affiliated with the business center to store inventory in.53 The Chinese negotiators also requested that the Chinese operators be allowed to determine and adjust the prices of the goods to be sold in the center.54 If the Beninese negotiators had accepted this clause and later changed their minds, Benin would have been compelled to compensate the Chinese side for the losses incurred.

In proposed clauses on duties and tax exemptions, the Chinese negotiators also requested more generous terms than allowed by Beninese national regulations, seeking exemptions for the costs of vehicles, training, registration stamps, management fees, and technical services, as well as the salaries of the Chinese workers and operators at the business center.55 The Chinese negotiators also requested that the profits of Chinese firms operating in the center be tax exempt up to a certain unspecified maximum, the materials for maintaining and refurbishing the center, and advertising and publicity campaigns to promote the center’s activities.56

As these details show, the Chinese negotiators made a variety of demands often in strategically vague language designed to maximize their own negotiating position.

Benin’s Coordinated Response and Subsequent Negotiations

After receiving the draft contract from their Chinese counterparts, the Beninese negotiators retook the initiative by holding a thorough, proactive multistakeholder review, which led to significant changes. In 2006, it was customary for specific ministries designated to represent the Beninese government to review and revise urban infrastructure contracts and to coordinate with other relevant ministries to review the terms of such deals.57 For this particular contract, the primary Beninese ministry involved was the Ministry of Environment, Habitat and Urbanism, which acted as a focal point to coordinate the contract review with the other ministries.

The ministry organized a negotiation retreat in Lokossa in March 2006, inviting a large array of line ministries58 to review and discuss the draft including the Ministry of Industry and Commerce, the Ministry of Labor and Public Service, the Ministry of Justice and Legislation, the Directorate General of Duties of the Ministry of Economy and Finance, the Directorate General of Budget, and the Ministry of Interior and Public Security.59 Given how many facets of Beninese economic and political life the draft could affect (including construction, the business climate, and taxes among others), each of the ministries’ representatives were given a formal opportunity to review specific clauses in light of existing regulations in their respective sectors and thoroughly assess how well the Chinese-proposed clauses complied with local regulations, norms, and practices.

This retreat in Lokassa offered the Beninese negotiators time and distance from their Chinese counterparts and any prospective pressure they might bring to bear. The Beninese ministerial representatives at the retreat proposed an array of amendments to the draft contract to ensure its terms aligned with Beninese regulations and norms. By enlisting the expertise of all these various ministries rather than letting a single ministry run point and call the shots, Beninese officials were able to maintain a united front and push their Chinese counterparts to adjust accordingly in the next round of negotiations.

According to the Beninese negotiators, the next round of negotiations in April 2006 with the Chinese counterparts took three “days and nights,” with a great deal of back and forth.60 The Chinese negotiators kept insisting on using the center as a platform for retail (not just wholesale) goods, but the Beninese Ministry of Industry and Commerce put its foot down and reiterated that this was legally not acceptable.

Overall, Benin’s multistakeholder marshalling of government-wide expertise allowed its negotiators to present a new draft contract to their Chinese counterparts more in line with Beninese regulations and norms. The Beninese government’s unity and coordination made it harder for China to try to divide and conquer by pitting parts of the Beninese bureaucracy against each other, forcing its Chinese counterparts to make concessions and abide by local norms and business practices. Beninese negotiators stayed aligned with the overarching presidential imperative to deepen the Benin-China economic relationship and formalize ties between the two countries’ respective private sectors. But they also managed to protect Beninese local markets from a flood of Chinese retail goods. This was significant because sharpening competition between local producers and Chinese rivals was already starting to stoke opposition to trade with China among Beninese businesspeople operating in large markets like the Dantokpa Market, one of West Africa’s largest outdoor markets.61

The retreat unified the Beninese government and helped Beninese officials adopt a more coordinated and coherent negotiating posture, to which China had to adjust. These negotiations help show how a smaller country can still hold its own in talks with a country as large as China when it coordinates and executes well.

The Effectiveness of Benin’s Follow-up Negotiations

Subsequent rounds of negotiation with China eventually led to a signed final contract in December 2006.62 Comparing the language of the initial draft contract and the final contract is a useful exercise.63 Because more detailed terms were swapped in for some of the vague clauses initially suggested by the Chinese negotiators, the final contract consisted of two main documents: one covering the construction of the center and another on the operationalization and transfer of the center. The changes that the Beninese negotiators proposed during the retreat were almost all integrated into the final terms.

For the project’s construction phase, specific deadlines were included in the final agreement. For instance, it was stipulated that the project’s feasibility and environmental studies had to be completed before construction could begin.64 It was also decided that the feasibility studies ultimately would have to be approved by the Beninese party, not the Chinese party, and a Chinese expert rather than a representative from the Chinese studies office would be sent to complete them.65 Furthermore, the salaries for Beninese workers would include a 10 percent raise during the construction phase.66

The Beninese negotiators also secured several revisions to the terms of the operationalization of the business center. These included the removal of all clauses that would have permitted the Chinese operators to sell retail goods in the business center, and the vague clauses authorizing the Chinese party to offer “business services” were also made more specific.67

The final contract also strengthened certain clauses by integrating more detailed references to existing Beninese regulations and standards. For instance, the clause in the original draft stipulating that Benin would not take any discriminatory measure against the center was edited to say that “Benin commits to assist the center in conformity with national legislation,” a boilerplate phrase that committed the Beninese side to nothing and asserted the primacy of Beninese laws in the governance of the center.68 Similarly, the problematic Chinese-proposed clause on exclusivity that would have made the Chinese business center the only such entity in Cotonou for the next thirty years was left out of the final contract; after all, such a demand was both legally impossible and, according to Beninese interviewees, judged not to be in line with Benin’s interests or legal standards.69 The Chinese negotiators did not ask the Beninese party to reconsider the clause.

In the section on the eventual transfer of the center, the Beninese party also added clauses that required the Chinese party to commit to renovating the center one year before it is transferred to Beninese control without receiving compensation for this work.70 Clauses demanding that the Beninese party take charge of all expenses related to the transfer were also specified and limited to administrative costs, registration fees, and expenses made on behalf of the Beninese party only, not activities undertaken by the Chinese side.71 By specifying what expenses would be included and who would be responsible for paying them, the Beninese negotiators put clearer limits on the payments that their Chinese counterparts had requested.

The sections of the contract on preferential treatment and tax exemptions were also made clearer and tilted in Benin’s favor. The Chinese request for additional land for storage purposes was not granted, but the Beninese party granted exceptional and temporary use of some land in case further development related to the center was needed.72 The final contract also stipulated that, while the prices of goods would be fixed by the center, there would be exceptions for goods whose prices are set by national Beninese regulations, once again establishing the primacy of Beninese law.73 A clause stipulating that recruitment and layoffs of Beninese workers would be made according to Beninese national regulations was added to the contract too.74

Most of China’s requests for formalized tax and duty exemptions did not make it into the final contract except for the wholesale goods used for exhibitions organized by the center, including those left over after such exhibitions.75 The final contract stipulated that the center’s operator would indeed be a Chinese company but one that ultimately would fall under Beninese laws and regulations.76

Lessons Learned

In the end, the Beninese negotiators succeeded in making their Chinese counterparts comply with Beninese legal statutes and norms. They managed to rewrite the contract in a much more detailed way that protected Benin’s interests without jeopardizing the project or the bilateral relationship with China. This success can be attributed to at least three factors. First, the Beninese government excelled at coordinating and adopting a united front to effectively ensure that all ministries’ expertise was leveraged to full effect, which meant slowing down the talks to ensure that certain clauses were considered thoroughly and made as specific as possible. Second, they referred repeatedly to national and international regulations and norms and sought to ensure that China accepted terms that aligned with these standards. Third, they were on guard against certain often-vague clauses on topics like unfair exclusivity claims, vague compensation terms, and especially in the case of business-related infrastructure contracts. Similarly, they resisted their Chinese counterparts’ push to give the center’s operators the right to sell retail as well as wholesale goods, which would have been particularly harmful to local businesses, including African merchants who source from China and might have otherwise been pitted in direct competition with Chinese merchants operating locally in Africa.

A few more words are warranted on the timing of the deal. Most of the negotiations took place during Kérékou’s second presidency, and he wisely allowed government officials and ministry bureaucrats to handle the details and execute the cross-ministry coordination without a great deal of political interference.77 Although the deal was ultimately finalized after his successor (Thomas Boni Yayi) took office, a great deal of the credit should go to Kérékou’s administration and the able bureaucrats who finalized the deal. Boni Yayi did not intervene much as the deal’s terms were finalized early in his presidency. That said, Boni Yayi did unfortunately change course when negotiating subsequent deals with China. His presidency was marked by hasty negotiations and bureaucratic conflict and competition between ministries on some subsequent highway deals and other infrastructure projects.78

For example, strategic road projects negotiated under Boni Yayi, like the Akassato-Bohicon project, regularly involved intervention from the highly influential executive branch, pressing for speedy negotiations and quick execution while disregarding the application of some labor and legal norms. This had a major impact in terms of variations in the negotiating outcomes: it shows that when the executive branch is too intrusive, the outcomes have tended to be less beneficial for Benin. In cases when the executive branch is more permissive, the bureaucrats negotiating the deal are more empowered to delve into a deal’s technical details and exert agency while seeking to preserve and uphold national laws and regulations.79

In the case of the business center, by taking their time, the Beninese negotiators were better able to ensure that the final contracts were longer and more specific than the initial draft. While the initial offer was a single document of thirty pages, the two documents laying out the terms of the final contract was split into two separate contracts totaling more than 100 pages.80 The Beninese negotiators managed to specify terms that the Chinese side preferred to leave vague. While the draft contract was marked by vague terms and loosely worded demands for certain concessions, the final contract outlined more thoroughly the standards and procedures for the construction, operationalization, and transfer of the center and how its revenues would be taxed. The final package of documents also included at least four subsections detailing the relevant Beninese laws that the agreement must uphold in the form of a question-and-answer document signed by both parties.81

Above all, the successful negotiations on the business center are an example of how African countries can sometimes exercise agency despite the asymmetrical nature of their relationships with China. One especially salient decision was to insulate negotiations with China from day-to-day political considerations and hand it off to capable Beninese bureaucrats. This choice formalized and regularized the process and gave the negotiations a depoliticized sense of continuity. The bureaucrats who spearheaded the talks were first and foremost civil servants (rather than presidential advisers or political appointees), and they were invariably perceived as such by their Chinese counterparts. This approach helped ensure that the primacy of Beninese laws, regulations, and customs would be respected.

This is a good lesson for other countries but especially African states. The exercise of bureaucratic agency in negotiations on infrastructure projects can lead to more favorable outcomes, as the case of the business center in Benin shows. Even small African states like Benin can benefit from such an approach.

How the Center Has Affected Benin-China Business Relations

This Benin-first approach has paid dividends since the business center became operational. Engaging with the Beninese private sector has become a priority for Chinese businesses operating in the country. The center’s Chinese operators have increasingly understood that they need to build strong relationships with local actors and adapt to their methods and business practices to penetrate the Beninese and West African markets.

Since the business center opened, it has proven to be an active economic hub. It organizes annual business fairs to market wholesale products and arranges meetings between Beninese businesspeople and prospective Chinese business partners.82 In 2018, the center organized a special fair with exhibitors from Yiwu and Ningbo, and the Chinese contractors present at the center were also represented at larger national fairs in Benin such as the Independence Fair, organized in August 2018 in Cotonou.

The center also offers an array of other services. It gives business trainings to Beninese and West African small- and medium-sized enterprises who aim to supply consumer goods from China.83 The center also offers offices and conference rooms, trade and regulatory advisory services (for Chinese enterprises), assistance with registering Chinese companies in Benin and obtaining personal residence permits for Chinese business leaders in Benin, advertising services, and help with arranging meetings and liaisons between prospective Chinese and Beninese business partners. Official trade flows also have soared between Benin and China since the opening of the center, despite a slowdown between 2008 and 2010 (see figure 1) due to the 2007–2008 global financial crisis. From 2013 onward, China has remained Benin’s top external trade partner.84

When the coronavirus pandemic struck in early 2020, trade of goods between China and Benin was affected by the global low level of trade flows and the temporary suppression of maritime and air routes.85 The gradual reopening of these routes in West Africa in late 2020 and 2021 allowed the Chinese business center to play a key role of acting as a liaison office between Chinese and African businesses operating in both Benin and China. Most Beninese businesses operating initially in the informal sector and who were organizing their business relations directly via suppliers in China got hit by supply chain disruptions involving these suppliers or the closure of supplier firms in China amid the pandemic.86

Many Beninese businesses started using the center’s services to find new suppliers in China. The growing demand led to large queues at the entrance of the center and an increase in registration of these informal businesses in Benin’s national commercial register as firms sought to benefit from the center’s business services.87 In this respect, the center’s objective of formalizing better Benin-China business-to-business relations has been partially met even in very challenging circumstances.

Notes

1 Giles Mohan and Ben Lampert, “Negotiating China: Reinserting African Agency Into China-Africa Relations,” African Affairs 112, no. 446 (January 2013): 92–110, https://academic.oup.com/afraf/article/112/446/92/10208.

2 This paper relies on original research and fieldwork conducted in Benin from 2015 to 2021; the author’s access to draft and final contracts of the negotiations; and field interviews with key players that were part of the Beninese negotiating team, and senior representatives from the Beninese Chamber of Industry and Commerce (Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie du Benin), the Beninese National Council of Employers (Conseil National du Patronat), and Beninese merchants.

3 Kingsley Ighobor, “China in the Heart of Africa,” Africa Renewal, January 2013, https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/january-2013/china-heart-africa.

4 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “World Investment Report – Investing in Sustainable Recovery,” June 2021, https://unctad.org/fr/node/33319.

5 UNCTAD, “UNCTAD Stat: International Merchandise Trade,” 2021, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx?sCS_ChosenLang=en.

6 “Five Facts About Informal Economy in Africa,” International Labour Organization, June 18, 2015, https://www.ilo.org/africa/whats-new/WCMS_377286/lang--en/index.html.

7 Leandro Medina, Andrew W. Jonelis, and Mehmet Cangul, “The Informal Economy in Sub-Saharan Africa: Size and Determinants,” International Monetary Fund (Working Paper), July 2017, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2017/07/10/The-Informal-Economy-in-Sub-Saharan-Africa-Size-and-Determinants-45017.

8 Chen Zhimin and Jian Junbo, “Chinese Provinces as Foreign Policy Actors in Africa,” South African Institute of International Affairs, Occasional Paper no. 22, January 2009, https://media.africaportal.org/documents/SAIIA_Occasional_Paper_no_22.pdf.

9 Katy Lam, “L’inévitable ‘Localisation’: les Entreprises Publiques Chinoises de la Construction au Ghana [The Inevitable “Localization”: Chinese State-Owned Construction Companies in Ghana] Politique Africaine, no.134 (June 2014): 21–43, https://www.cairn.info/revue-politique-africaine-2014-2-page-21.htm.

10 Antoine Kernen et al., “China, Ltd. Un Business Africain” [China, Ltd.: An African Business], Politique Africaine, no. 134, June 2014, https://www.cairn.info/revue-politique-africaine-2014-2.htm.

11 Alejandro Portes, “La Mondialisation par le Bas” [Globalization From Below] in Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales [Acts of research in the social sciences] 4, no, 129 (1999): 15–25 https://www.persee.fr/doc/arss_0335-5322_1999_num_129_1_3300

12 Kernen et al., “China, Ltd. Un Business Africain” [China, Ltd.: An African Business].

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Kenneth B. Noble, “French Devaluation of African Currency Brings Wide Unrest,” New York Times, February 23, 1994, https://www.nytimes.com/1994/02/23/world/french-devaluation-of-african-currency-brings-wide-unrest.html.

16 Mohan and Ben Lampert, “Negotiating China.”

17 Mario Esteban, “A Silent Invasion? African Views on the Growing Chinese Presence in Africa: the Case of Equatorial Guinea,” African and Asian Studies 9, no. 3 (2010), 232–251, https://brill.com/view/journals/aas/9/3/article-p232_4.xml.

18 Mohan and Ben Lampert, “Negotiating China.”

19 World Bank, “Population Total – Benin,” World Bank, 2020, https://donnees.banquemondiale.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=BJ.

20 Author interview with a Beninese businessman who was a former student in China, Cotonou, May 2015.

21 Ibid.

22 Folashade Soule, “Bureaucratic Agency and Power Asymmetry in Benin‐China Negotiations” in New Directions in Africa-China Studies, ed. Chris Alden and Dan Large, (London: Routledge, 2018), https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315162461-12/bureaucratic-agency-power-asymmetry-benin%E2%80%93china-relations-folashad%C3%A9-soul%C3%A9-kohndou; and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “International Merchandise Trade,” UNCTAD, 2021, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx?sCS_ChosenLang=en.

23 Author interview with a senior policy official, Beninese Ministry of Industry and Commerce, Cotonou, May 2015.

24 Author interview with a Beninese businessman who was a former student in China, Cotonou, April 2015.

25 Author interview with a Beninese businessman who was a former student in China, Cotonou, April 2015.

26 Author interview with a Beninese businessman who was a former student in China, Cotonou, May 2015.

27 Author interviews with a former Beninese student in Benin during the early 1980s, Cotonou, May 2015.

28 Ibid.

29 Author interview with the director of the Beninese National Council of Employers (Conseil National du Patronat Béninois), Cotonou, June 2014.

30 Individual author interviews with Beninese businessmen who were formerly students in China in the early 1980s, Cotonou, May 2015.

31 Government of Benin, “Protocole Portant une Création du Centre Chinois de Développement Commercial et Économique au Benin” [Memorandum of understanding on the creation of a Chinese center of business and economic development in Benin], January 1998. See the following project timeline for more detailed information: China-Benin Economic Development and Business Center, “Apercu Du CCDECB,” [Overview of the CCDECB], China-Benin Economic Development and Business Center, http://benincenter.com/bn/fcabout.asp.

32 This information is included in a timeline of the center’s evolution. See China-Benin Economic Development and Business Center, “Apercu Du CCDECB,” [Overview of the CCDECB].

33 The transfer would cost the Beninese government a symbolic amount: 1 CFA franc. Ibid.

34 Author interview with a senior policy official at the Directorate of Construction, Ministry of Environment, Habitat, and Urbanism, Cotonou, April 2015.

35 The author obtained access to archival materials of the negotiations, including both the draft contracts and final contracts, during field work and conducted interviews with officials at the Beninese Ministry of Environment, Habitat, and Urbanism.

See Government of Benin, “Contrat de Construction du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin - CCDECDB” [Contract for the construction of the Chinese economic and commercial development center in Benin] (draft contract), February 2006; Government of Benin, “Contrat de Construction du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin” [Contract for the construction of the Chinese economic and commercial development center in Benin] (final contract on construction), December 2006; and Government of Benin, “Contrat d’Exploitation et de Transfert du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin” [Contract for the operation and transfer of the Chinese center for economic and commercial development in Benin] (final contract on operation and transfer), December 2006.

36 Peterson Nnajiofor, “Chinese and Western Investments in Africa: A Comparative Analysis,” International Critical Thought 10, no. 3 (2019): 473–482, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/21598282.2020.1846583.

37 Author interview with a senior policy official at the Directorate of Construction, Ministry of Environment, Habitat, and Urbanism, Cotonou, April 2015

38 Government of Benin, “Mémorandum de la Visite de la Delegation Chinoise pour le Projet de la Construction du CCDECB” [Memorandum of the visit of the Chinese delegation on the CCDECB construction project], (internal document), March 2002.

39 Government of Benin, “Mémorandum sur la Construction du CCDECB” [Memorandum on the construction of the CCDECB], (internal document), April 2004.

40 Government of Benin, “Contrat de Construction du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin - CCDECDB” [Contract for the construction of the Chinese economic and commercial development center in Benin] (draft contract), February 2006.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 Author interview with a senior policy official at the Directorate of Construction, Ministry of Urbanism and Habitat, Cotonou, April 2015.

48 Government of Benin, “Contrat de Construction du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin - CCDECDB” [Contract for the construction of the Chinese economic and commercial development center in Benin] (draft contract), February 2006.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 Katy N. Lam, “Chinese State-Owned Enterprises in West Africa: Triple-Embedded Globalization,” in La Chine en Algérie: Approches Socio-économiques [China in Algeria: Socio-economic approaches] ed. Abderrezak Adel, Thierry Pairault, and Fatiha Talahite (New York: Routledge, 2017), xii, 172, https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/7902.

52 Government of Benin, “Contrat de Construction du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin - CCDECDB” [Contract for the construction of the Chinese economic and commercial development center in Benin] (draft contract), February 2006.

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid.

55 Ibid.

56 Ibid.

57 Author interview with a senior policy official at the Directorate of Construction, Ministry of Environment, Habitat, and Urbanism, Cotonou, April 2015.

58 The names of some of Benin’s government ministries have changed over the years. The names used in this paper are the ones from 2006 when negotiations were taking place. For an up-to-date account of the ministry names, see Government of Benin, “Les Ministères” [The Ministries], Government of Benin, https://www.gouv.bj/ministeres.

59 Author interview with a senior policy official at the Directorate of Construction, Ministry of Environment, Habitat, and Urbanism, Cotonou, April 2015.

60 Author interviews with several senior policy officials at the Directorate of Construction, Ministry of Environment, Habitat, and Urbanism, Cotonou, May 2015.

61 Guillaume Moumouni, “Domestic Transformations and Change in Sino-African Relations,” Center on China’s Transnational Relations, Working Paper no. 21, 2006, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331810977_Domestic_Transformations_and_Change_in_Sino-African_Relations.

62 While negotiations continued and a deal was reached, the swearing-in of a new president after April 2006 and the inauguration of a new government slowed down the final signing of the deal, which happened in December 2006.

63 The final contract is composed of two separate documents. The final documents used here for a side-by-side analysis are (1) Government of Benin, “Contrat de Construction du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin (CCDECB), [Contract for the construction of the Chinese economic and commercial development center in Benin] (draft contract), February 2006; (2a) “Contrat de Construction du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin (CCDECB),” [Contract for the construction of the Chinese economic and commercial development center in Benin] (final contract on construction), December 2006; and (2b) “Contrat d’Exploitation et de Transfert du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin (CCDECB),” [Contract for the operation and transfer of the Chinese center for economic and commercial development in Benin] (final contract on operation and transfer), December 2006.

64 Government of Benin, “Contrat de Construction du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin” [Contract for the construction of the Chinese economic and commercial development center in Benin] (final contract on construction), December 2006.

65 Ibid.

66 Ibid.

67 Ibid.

68 Government of Benin, “Contrat d’Exploitation et de Transfert du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin” [Contract for the operation and transfer of the Chinese center for economic and commercial development in Benin] (final contract on operation and transfer), December 2006.

69 Author interview with the director of the Directorate of Construction, Ministry of Environment, Habitat, and Urbanism, Cotonou, May 2015.

70 Government of Benin, “Contrat d’Exploitation et de Transfert du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin” [Contract for the operation and transfer of the Chinese center for economic and commercial development in Benin] (final contract on operation and transfer), December 2006.

71 Ibid.

72 Ibid.

73 Ibid.

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid.

76 Ibid.

77 Soule, “Bureaucratic Agency and Power Asymmetry in Benin‐China Negotiations.”

78 Ibid.

79 Ibid.

80 Government of Benin, “Contrat d’Exploitation et de Transfert du Centre Chinois de Développement Économique et Commercial au Bénin” [Contract for the operation and transfer of the Chinese center for economic and commercial development in Benin] (final contract on operation and transfer), December 2006.

81 Ibid.

82 “Centre Commercial Chinois” [Chinese Commercial Center], Facebook, https://m.facebook.com/1904738443104504.

83 “Zhongxin Jianjie” [An introduction to the center], China-Benin Economic Development and Business Center, http://www.benincenter.com/bn/.

84 UNCTAD, “International Merchandise Trade.”

85 Follow-up author interview with a Beninese businessman, Cotonou, September 2021.

86 Follow-up author interview with a Beninese businessman, Cotonou, September 2021.

87 Follow-up author interview with a Beninese businessman, Cotonou, September 2021.