South Korean Resilience in an Era of Contentious Globalization

The coronavirus pandemic has put many governments around the world on the defensive, as they have struggled to handle the public health emergency effectively. South Korea (along with Taiwan and New Zealand) have seen their global standing rise as they are some of the few democracies that have done better at holding the virus at bay. The scholar who coined the term soft power, Joseph Nye, recently lauded Seoul by saying “[South] Korea has set a very good example of the democracy which handled the pandemic well.”

In a tumultuous year, South Korea has been a reminder of how ordinary citizens and government officials can rally together even in very trying circumstances. But whether this success is credited to government competence or solidarity among citizens, Seoul has shown that such crises don’t always have to undermine the resilience of society as a whole—in fact, when hard challenges are met, such crises can even deepen such resilience. In this way, South Korea could be a model for other countries of effective public policy, a healthy respect for science, and resilience in the face of daunting challenges.

How the South Korean Government Have Managed the Pandemic

The South Korean government deserves credit for mounting an effective response to the pandemic. By skillfully mobilizing widespread testing, agile contact tracing, and efficient treatment, South Korea has done better than most countries at flattening the curve and curbing the spread of the virus. In part, this is because South Korea learned key lessons from the 2015 outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), when it had the second-largest number of infections after Saudi Arabia. After that outbreak, the South Korean government crafted an efficient pandemic response that relied heavily on an array of tactics. These included a contact tracing regime that made extensive use of personal information like GPS data, surveillance camera footage, and credit card transaction histories to effectively track individuals who may have been infected (see photo 1). When the current pandemic surfaced, this preparation paid off.

South Korea’s high-tech contact tracing app has been one of the world’s most successful campaigns of its kind, though it has raised privacy concerns in some quarters. (Source: Photo by Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images)

South Korea’s high-tech contact tracing app has been one of the world’s most successful campaigns of its kind, though it has raised privacy concerns in some quarters. (Source: Photo by Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images)

How South Korean Citizens Have Helped Curb the Pandemic

The government’s response likely would not have been as effective as it has been without citizens’ willing participation. Working together, government officials and citizens even smoothly pulled off the world’s first major election during the pandemic without a major spike in coronavirus infections (see photo 2). So far, many South Koreans have been much more supportive of the government’s efforts to manage the pandemic than their counterparts in other, especially Western, democracies. They have even tolerated government contact tracing using their mobile phones, while displaying fewer qualms about infringements on privacy than such proposals would presumably spark in many Western democracies, where even smaller gestures like wearing masks have proven controversial to some. Indeed, in parts of the United States and Europe, there are those who would see such disclosures of personal information and other pandemic-era restrictions as a grave threat to their individual privacy and personal freedom. Compared to people in parts of Europe and the United States, South Koreans seem less concerned about their freedom being violated during the pandemic than they are about keeping the virus under control.

South Korea instituted stringent preventative measures to ensure that voters in the April 2020 election could vote safely without triggering a rise in coronavirus cases. (Source: Photo by Jung Yeon-je/AFP via Getty Images)

South Korea instituted stringent preventative measures to ensure that voters in the April 2020 election could vote safely without triggering a rise in coronavirus cases. (Source: Photo by Jung Yeon-je/AFP via Getty Images)

Of course, such compliance is hardly universal in South Korea. Some South Koreans have argued that the pandemic has triggered a new authoritarian-style government. They argue that the government has sought to expand its clout over its citizens and legitimize the suppression of individual rights under the pretext of the public health crisis. And just because South Koreans are abiding by public health guidelines doesn’t mean they are ignoring the privacy tradeoffs altogether. Many are worried that the government could take advantage of citizens’ compliance, leading to massive government surveillance practices that could outlive the pandemic.

Nonetheless, most South Koreans have complied. Some have chalked up such compliance to cultural factors in South Korea that don’t seem to hold water. For instance, at least a few observers have pointed to the prevalence of Confucian traditions in South Korea, which teach its followers to unconditionally obey political leaders. But that explanation doesn’t seem to work. After all, some of the very same citizens who have mostly adhered to the government’s pandemic stipulations were those who instigated the massive street protests of the 2016 Candlelight Revolution that resulted in the impeachment of then president Park Geun-hye (see photo 3). Cultural factors like Confucianism can’t explain why South Koreans have abided by government orders now but were in the streets demonstrating only a few years ago. While the circumstances of the two cases are very different, a citizen-driven commitment to the public good in the face of national emergencies is evident in both instances.

Massive crowds of protesters in Seoul and other major cities applied public pressure for months until then president Park Geun-hye was ultimately impeached in March 2017. (Source: Photo by Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images)

Massive crowds of protesters in Seoul and other major cities applied public pressure for months until then president Park Geun-hye was ultimately impeached in March 2017. (Source: Photo by Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images)

Most South Korean citizens are cooperating with the government’s all-out pandemic response by voluntarily restricting their movements and wearing masks, among other actions. This widespread public cooperation in South Korea presented a sharp contrast the United States, where many people famously flocked to crowded beaches over the summer, protested economic lockdowns, and declined to wear masks despite the warnings of government officials and public health experts.

Although the South Korean government has passed economic stimulus measures, many are concerned that the pandemic will have severe, long-term economic repercussions. How long South Koreans are willing to support the government’s pandemic control measures remains to be seen. If economic hardships persist, their patience could very well run out. For the most part, the government has received high marks for its handling of the pandemic so far, but this doesn’t mean that public support can be taken for granted. The Blue House has been flooded with online petitioners who are angry over the government’s rosy promises of an economic revival. Like politicians anywhere, South Korean politicians are sensitive to public opinion and the potential risk of rising populism in the wake of the economic suffering the pandemic has unleashed. In short, public compliance with the government’s public health measures won’t be a shield of immunity from political pressures to alleviate the economic toll of the public health emergency.

A Potential Antidote to the Excesses of Globalization

The important ties that bind South Korean government officials and ordinary citizens—a robust participatory democracy combined with an abiding sense of civic responsibility—would be difficult to overstate. The effectiveness of South Koreans’ response to the pandemic speaks for itself. Societal resilience of the kind South Korea has demonstrated could be all the more useful in an era of highly disruptive and contentious worldwide responses to the forces of globalization, especially when compared to the performances of more established soft power leaders such as the EU and the United States.

Globalization will become even more contentious, though neither South Koreans nor people anywhere else can force it back into the bottle or roll it back. Globalization will remain an indelible element of life in South Korea. This will hold true as long as the South Korean economy depends on critical linkages with the world economy including the country’s exports and oil and natural gas imports. Yet, at the same time, if South Korea’s resilient citizens continue to embrace grassroots democracy, human rights and civic freedoms, and (crucially) civic duties, that resilience will also continue to be an unmistakable dimension of South Korean global standing.

The Limits of Soft Power in Japan–South Korea Relations

Given South Korea’s notoriously rocky relationship with Japan, cultural exchange may seem a promising bridge to reconciliation. It’s certainly possible. In past centuries, Korean craftwork and artistry sometimes have represented for Japan the apogee of aesthetic sensibilities. And as is true in much of the world, South Korean popular culture is again in vogue in Japan. Like in so many endeavors between the two countries, however, cultural exchange must reckon with historical baggage and a fierce, ongoing competition.

How South Korean Pop Culture Fares in Japan

If there is a bright spot in Japan–South Korea ties, it has to be cultural products. In a 2019 survey by the Japanese think tank known as The Genron NPO, 49.5 percent of Japanese respondents credited South Korean “dramas, music or culture” for any positive impressions they had of the country. That figure is eclipsed only by South Korean food and shopping (52.5 percent); no other factor (even shared democratic values) came within twenty percentage points.

In modern times, Japan’s vogue for South Korean popular culture (like in the rest of Asia) goes back to the debut of the 2002 television drama Winter Sonata. The show tugged at the heartstrings of Japanese viewers especially tightly. After it debuted, a flood of Japanese tourists made pilgrimages to South Korean sites made famous by the show: Japanese visitors to the city of Chuncheon, where the drama was set, leaped from 40,000 to 140,000 per year.

In Seoul, those tourists collected souvenirs from the show at Namdaemun Market; the scarf that star Bae Yong-joon wore was everywhere. During Bae’s first visit to Tokyo, a stampede of unruly fans trampled each other to get close; ten of them ended up in the hospital. The Japanese prime minister at the time, Junichiro Koizumi, went as far as to say, “Bae Yong-joon is more popular than I am in Japan.”

Other South Korean cultural sensations have followed Winter Sonata in the past few years. The boy band BTS has become a globally recognized sensation. Four of the group’s albums have reached the top of the Billboard charts, and in 2019, BTS reportedly accounted for nearly $4.7 billion of South Korea’s GDP ($1.6 trillion). Parasite, a highly vaunted dark comedy, won four Academy Awards in 2020, including Best Picture—becoming the first non-English language movie to claim that honor. Television shows like Crash Landing on You and Itaewon Class are “reigniting the Japanese people’s interest in South Korean pop culture.”

South Korea’s success with cultural exports is no fluke. Since the Asian financial crisis, when then president Kim Dae-jung championed a 1999 law to promote the country’s cultural wares, successive South Korean governments have pushed the cultural and entertainment industries to diversify the nation’s economy and strengthen its international reach. In doing so, the government has explicitly focused on developing Seoul’s soft power. Yet cultural popularity alone does not guarantee soft power.

Where South Korean Pop Culture Falls Short in Japan

As Harvard professor Joseph Nye observed, when possible, countries seek to lead by the power of their ideals rather than by coercion. This approach is logical and attractive, especially to countries that lack the resources or size to wield sufficient hard power. Unfortunately, soft power has also devolved into a conceptual grab bag that mistakes appeal for power and popularity for influence. While there is no contesting the popularity of South Korea’s cultural products, it is another thing to call them a source of soft power.

The gap between the high regard Japanese people have for South Korean culture and the dismal state of the bilateral relationship is quite large. In the same 2019 survey by The Genron NPO, Japanese views of South Korea as a whole were grim: only 8 percent viewed South Korea as a “friendly nation,” while a combined 43.9 percent felt it no longer was or never had been. Sadly, those findings align with the 2019 results of the annual Cabinet Office survey of Japanese diplomacy: a whopping 87.9 percent viewed the relationship as “bad” or “very bad.”

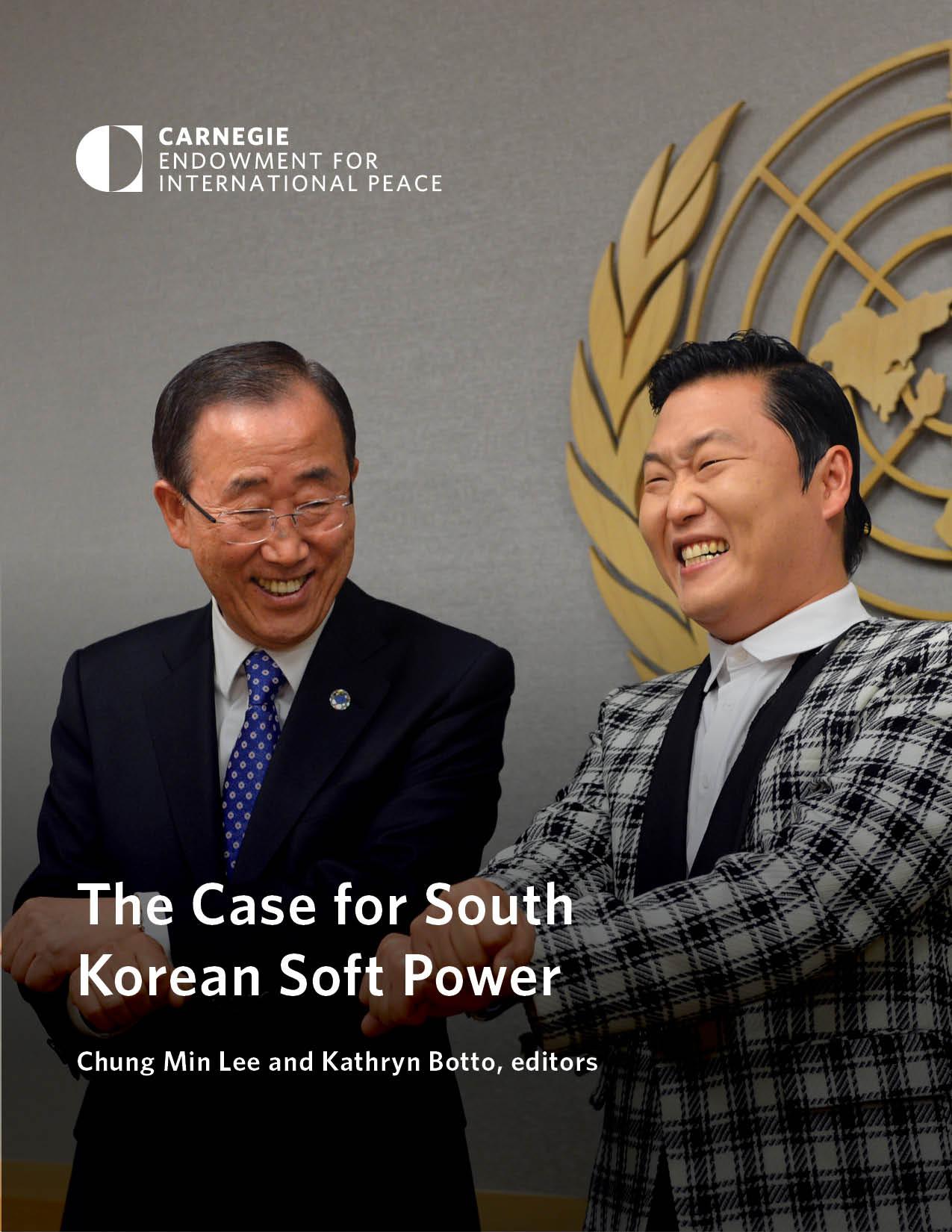

That diplomatic chasm shows how difficult it can be for a country to translate a general appreciation of its culture into actual power (see video). Lots of people listen to BTS, get a laugh out of Psy’s antics in “Gangnam Style,” and watch Parasite, but they couldn’t care less about the South Korean government’s policy preferences. Even a growing flood of tourism revenue doesn’t mean that other countries—either their citizens or their governments—would back South Korea on vital diplomatic issues.

The survey by The Genron NPO drives that point home. When asked how to improve the bilateral relationship, Japanese respondents almost invariably pointed to deep-rooted problems that cultural goodwill alone is unlikely to solve. More than 53 percent called for resolving historical issues (like the dispute over the treatment of comfort women or wartime laborers during World War II), 41.3 percent called for solving the country’s territorial dispute, and nearly 40 percent endorsed “fixing historical perception and education issues.” By contrast, just 22.4 percent said the answer lies in building trust through private dialogue and exchanges, and a mere 13.2 percent thought tourism is the fix.

In addition, there is an ironic twist to South Korea’s cultural success that could undermine its soft power. The musical juggernaut of K-pop and acclaimed but incisive films like Parasite at times invite scrutiny of the country’s dark side. The headline the Japanese newspaper the Nikkei ran after the film’s Oscar win made the point excruciatingly clear: “South Korea’s ‘Parasite’ Celebrations Tiptoe Around Brutal Message.” That article applauds director Bong Joon-ho for taking a hard look at the disparities and “frustration” that mark life for the working class in South Korea and elsewhere in the world.

The same article credits the members of BTS for “their frank discussion of depression and other issues plaguing young people in South Korea and abroad.” Among those problems are the suicides of K-pop stars. Consider the headline of another Nikkei article—“K-pop Deaths Highlight South Korea’s Desperation for Soft Power.” It reveals both the pressures that those stars live with and the intensely competitive prism through which Japan views South Korea’s cultural success. With unmistakable schadenfreude, Nikkei concludes, “South Korea differs starkly from the postcard vision the nation likes to project abroad.”

Conclusion

As in other dimensions of the Japan–South Korea relationship, the delights of cultural exchange have been diluted by the weight of history. While South Korea’s culture deserves a wider audience and its soft power is growing in tandem with this broader popularity, it is always important to recognize the limits of those endeavors and to remember the value of traditional diplomacy. Fixing the very real problems that plague relations between South Korea and Japan will require work in both countries by politicians and thought leaders who are committed to reconciliation and a forward-looking agenda. The process will be slow, frustrating, and even sometimes painful, but it is well worth those difficulties.

Brad Glosserman is deputy director of and visiting professor at the Center for Rule-Making Strategies at Tama University as well as senior adviser (nonresident) at Pacific Forum. He is the author of Peak Japan: The End of Great Ambitions (Georgetown University Press, 2019), which was recently translated into Korean.

Can Soft Power Enable South Korea to Overcome Geopolitics?

South Korea has long found itself in the unenviable position of being a midsized power in a tense neighborhood of geopolitical titans. Many South Koreans rightly ask whether the country’s soft power can help Seoul transcend, even partially, the geopolitical fate Northeast Asia has given it or at least blunt the sharpest edges of the region’s hard power calculations and geopolitics. Soft power has inherent limitations, but it can serve as a conduit for expanding South Korean influence on some critical transnational issues. Combating climate change; cultivating sustainable macroeconomic growth; and reaffirming universal values like human rights, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press all come to mind.

But for all its uses, the limits of soft power are real. Sandwiched as South Korea is between some of the world’s most powerful states—China, Japan, Russia, and the United States—soft power won’t be able to sway Seoul’s neighbors on all thorny geopolitical issues. Even if South Korea accumulates more soft power, it’s unrealistic to expect Seoul’s soft power to alleviate crucial geopolitical tensions such as the accelerating U.S.-China rivalry. While South Korea must keep its expectations for soft power modest, it shouldn’t overlook the potential benefits of soft power either.

Over the past several years, Chinese pressure on South Korea has grown. Beijing insists that Seoul shouldn’t forge deeper military ties with the United States—South Korea’s most indispensable ally. China also asserts that South Korea should minimize, if not stop, security ties between Seoul, Washington, and Tokyo. Of course, the main reason South Korea continues to have a critical alliance with the United States is North Korea’s expanding threat portfolio, including its burgeoning nuclear weapons program. And so long as China continues to coddle and provide a lifeline to North Korea, Pyongyang’s asymmetrical threats against South Korea, as well as those against the United States and Japan, will only increase. Credible deterrence and defense capabilities remain the linchpins of South Korean security.

But soft power could help South Korea carve out the kind of diplomatic and multilateral spaces that are likely to become increasingly prominent in the post-pandemic world to come. This is true in at least four areas:

- the rising importance of societal resilience and nimbleness in terms of addressing transnational threats;

- the increasing relevance of hybrid power as advanced technologies, adaptable markets, social cohesiveness, and proactive policymaking come into play;

- the heightened salience of local South Korean policy solutions that can be adapted regionally and globally and thereby enhance the country’s global brand; and

- the growing premium being placed on South Korea’s complementary, middle-power status as a robust democracy

As Seoul’s international standing has increased significantly with its relatively successful handling of the coronavirus pandemic, South Korea’s soft power has also garnered wider recognition. Since the 1970s, South Korean hard power has grown on the heels of the country’s accelerated economic growth, an element of the country’s national story that has received the lion’s share of the attention to date. In the 1970s and 1980s, rapid South Korean advances in ship building, automobiles, steel manufacturing, and consumer electronics symbolized the country’s coming of age. A June 6, 1977, Newsweek cover story in the international edition entitled “The Koreans Are Coming” captured the prevailing mood. In a 2020 report, the Australian think tank the Lowy Institute ranked South Korea and other Asian-Pacific countries on a range of metrics. These included (among others) comprehensive power, military capability, economic capability, diplomatic influence, and cultural influence. Seoul ranked in the middle of the pack across the board (see table 1).

| Table 1. Ranking Asian-Pacific Powers | |||||

| Rank | Comprehensive Power* | Military Capability | Economic Capability | Diplomatic Influence | Cultural Influence |

| 1 | United States | United States | China | China | United States |

| 2 | China | China | United States | Japan | China |

| 3 | Japan | Russia | Japan | United States | Japan |

| 4 | India | India | India | India | India |

| 5 | Russia | South Korea | South Korea | South Korea | Australia |

| 6 | Australia | North Korea | Russia | Russia | Malaysia |

| 7 | South Korea | Japan | Singapore | Australia | South Korea |

| 8 | Singapore | Australia | Taiwan | Singapore | Thailand |

| 9 | Thailand | Pakistan | Australia | Vietnam | Singapore |

| 10 | Malaysia | Singapore | Indonesia | Indonesia | Russia |

| Source: Lowy Institute, Asian Power Index: 2020 Key Findings, 2020, https://power.lowyinstitute.org/downloads/lowy-institute-2020-asia-power-index-key-findings-report.pdf. *This table includes four of the eight measures that comprise the Lowy Institute’s comprehensive power ranking. |

|||||

South Korea’s transition from decades of authoritarian rule to democracy in 1987 added a new dimension to the country’s national tale. Although all sectors of South Korean society opened up after democratization, the country’s artistic and cultural spaces really flourished. In 2020, for instance, the South Korean movie Parasite won four Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Meanwhile, K-pop began to gain global attention in the 2010s, as shown by the popularity of the singer Psy’s “Gangnam Style” music video and more recently with the astounding success of the boy band BTS: as this success has grown, South Korean soft power has begun to receive serious attention.

There is little doubt that South Korea’s soft power is on the rise. According to Brand Finance’s 2020 “Global Soft Power Index” report, South Korea was ranked fourteen out of sixty listed countries. (Figure 1 below highlights the report’s top thirty rankings.) Former UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon noted in the report’s introduction, “In today’s era of increasing nationalism, uncertainty, and transnational challenges, I am of the view that soft power is now more important than ever.” Similarly, the University of Southern California’s “Soft Power 30” report creates composite scores of countries’ overall soft power. It does so by combining data in six areas (government, digital, culture, enterprise, engagement, and education) and polling data in seven areas (cuisine, tech products, friendliness, culture, luxury goods, foreign policy, and livability). In the report’s 2019 edition, South Korea ranked nineteen of thirty with a total score of 63 out of 100. Among countries in Asia, Japan came out on top with 75.7, followed by South Korea (63), Singapore (61.5), and China (51.3).

Two major lessons can be gleaned from the pandemic and the world’s greater receptiveness to South Korean soft power. First, soft power provides South Korea with a starkly different image than China, as Seoul presents itself as an open and democratic society, albeit one where traditional norms and cultural heritage co-exist side-by-side. Unlike China’s binary worldview of itself versus the rest of the world, South Korea provides a new model of what a twenty-first-century Asian country can look like: an advanced economy mixed with an ancient civilization that is at once irrevocably democratic, technologically innovative, and culturally vibrant. Second, while there are definite constraints on how much South Korea can emphasize human rights in the conduct of its foreign policy, Seoul should play a much more important role in bringing to light the abysmal human rights record of its northern neighbor, North Korea. As a liberal democracy, South Korea has the duty to speak out on, promote, and help preserve human rights.

In the early 1970s, as South Korea’s so-called economic surge known as the Miracle on the Han River was about to take off, it would have been impossible to imagine the place the country has taken today on the world stage. Soft power will never replace hard power. But used adroitly, it can provide South Korea with advantages that some of its much more powerful neighbors don’t have. These advantages could prove timely, as South Korea faces enormous challenges including a rapidly aging society, one of the world’s lowest birth rates, and rising youth unemployment. Of course, the country also confronts sobering geopolitical challenges too.

But overall, South Korea is in a much better place now than it was in the early twentieth century when it lacked power—hard, soft, and everything in between—and had a society and leadership that failed to make fundamental adjustments. South Korea won’t ever be able to fully compensate for the weight of geopolitics on its national fortunes, but if Seoul can harness and make good use of all facets of its hybrid power (including soft power), it can surely improve its outlook going forward, even if only on the margins.

How Multiculturalism Has Fared in South Korea Amid the Pandemic

South Korea’s successful response to the coronavirus pandemic has elevated its global profile and created openings for its reserve of soft power to grow. But as the pandemic continues, it is worth noting that looking only at South Korea’s successes may provide a distorted view of the potential soft power gains the country could make.

Widening the aperture to include South Korea’s shortcomings might provide a fuller, more clarifying picture of the country’s global image and soft power as a whole. South Korea’s marginalization of foreigners and migrants in its pandemic response provides a cautionary tale about the status of the country’s multiculturalism strategy, an important part of Seoul’s state-driven quest for economic dynamism, global standing, and soft power.

Why Did South Korea Embrace Multiculturalism?

Traditionally, South Korea has identified as an ethnically homogenous country, as Korea scholars like Gi-Wook Shin and Darcie Draudt have extensively chronicled. Despite this legacy of homogeneity, demographic trends have pushed South Korean policymakers to encourage inbound migration, leaving politicians and citizens alike to grapple with the prospect of their country becoming a more multiethnic state.

Since the early to mid-1980s, South Korea’s fertility rate has remained below 2.1 children per woman—the rate considered necessary to replace the population over a generation without migration. The country’s figure stood at just 0.98 in 2018, according to the World Bank (see figure 1). Meanwhile, average life expectancy has risen from sixty-six years old to eighty-two years old over that same period, even as South Korea’s population growth has slowed precipitously. These changes are leading to labor shortages in important economic sectors and changes in marriage trends, creating a demand for migrant labor and foreign spouses.

Since the early 2000s, the government has embraced more liberal immigration policies and actively promoted multiculturalism. Seoul’s goal is not only to persuade the country’s predominantly Korean population to accept this shift but also to make South Korea a more appealing draw for labor migrants, foreign spouses, and international students.

In practice, this shift has been slow going and has faced some backlash—both mutually reinforcing trends. In the last twenty years, the percentage of foreign residents in South Korea has gone from 0.33 percent in 2000 to 3.44 percent in 2019 (see figure 2). Cognizant of societal sensitivities to immigration, South Korean policy planners have sought to ease the resistant country into new immigration policies, but such domestic sensitivities also hinder implementation of more comprehensive immigration policies. For example, importation of migrant labor has been a bedrock of South Korea’s response to its demographic challenges, but the country’s labor visa system ensures that most migrant laborers remain temporary residents. As Draudt notes, the country’s Employment Permit System (EPS) stipulates that migrant laborers can obtain renewable one-year visas “until just shy of the five years needed to apply for long-term residency.”

How the Pandemic Has Tested South Korean Multiculturalism

The foreign-borne, highly contagious, and potentially lethal coronavirus pandemic raises hard questions for South Korean policymakers about how to allocate precious resources and how to manage exposure risks. However unintentionally, South Korea has marginalized foreigners and migrants in its pandemic response. This response is arguably symptomatic of the country’s difficult relationship with its growing foreign and migrant communities and exposes the challenges multiculturalism continues to face.

First, there continue to be tensions between the state’s perceived responsibilities toward foreign residents and those residents’ expectations of equitable treatment under the law. Like in many countries, national and local South Korean officials offered varying levels of economic relief to citizens and residents but not foreigners. In places with lots of foreign residents like Seoul and Gyeonggi, for instance, government officials placed stricter eligibility conditions on non-Koreans or even excluded them from receiving economic aid altogether. Following complaints filed by civic and human rights groups, the independent National Human Rights Commission of Korea concluded that the exclusions were discriminatory and made a nonbinding recommendation that all foreign residents should be eligible to receive pandemic-related assistance. Seoul’s municipal government reversed course and complied with the recommendation, but Gyeonggi’s provincial government chose not to, citing logistical and legal challenges.

Foreign residents living in South Korea are economically vulnerable. The majority of them work in low-paying nonprofessional jobs or perform manual labor and therefore have been hit hard by the pandemic. These jobs are essential to South Korea’s economy, especially as increasing incomes and educational levels in the country have led to a domestic shortage of low-skilled workers. But aside from the economic importance of inclusion, this example of exclusionary policymaking shows a disconnect between South Korea’s inclination to marginalize non-Koreans and its pro-multiculturalism policy.

Second, against prevailing public health recommendations, South Korea has targeted foreigners in its disease mitigation strategies, perhaps reinforcing discrimination that is already on the rise. As individuals infected with the coronavirus were increasingly seen as coming from abroad, South Korea began to implement stringent deportation regulations for foreign nationals caught violating quarantine measures. The government also revised national law so that foreigners would be required to pay for the cost of treating any coronavirus-related illnesses if they knowingly traveled to South Korea while infected.

South Korean policymakers are understandably overwhelmed with trying to manage new viral outbreaks, and these exclusionary measures were likely narrowly aimed at curbing imported cases and disincentivizing uncooperative behavior. But such discriminatory policies based on foreign or migrant status have been widely condemned as bad public health policies that could further the global spread of the disease or discourage marginalized groups from seeking treatment.

The measures also feed into a xenophobic narrative that the government should be actively combating. Early on in the pandemic, anti-Chinese racism reportedly flared up, as delivery services refused to travel to areas with Chinese migrants and as some shops and restaurants shunned Chinese people because of racist views that the coronavirus is a “Chinese virus.” This trend indicates a larger backlash against multiculturalism and enduring racism in the country. According to a 2019 survey, 68.4 percent of migrants interviewed agreed that racism is a problem in South Korea.

To be fair, many countries are struggling to balance how they treat migrant and immigrant communities in their national pandemic responses. The United States, for example, also excluded tax-paying nonpermanent residents from stimulus relief, and the country has seen a significant rise in anti-Asian racism. There is a soft power lesson here, too, for South Korea. The United States’ soft power appeal has been seriously undermined by President Donald Trump’s America First foreign policy agenda and related racist immigration policies and rhetoric. Clearly, perceptions about multiculturalism matter.

Conclusion

The disruptive coronavirus pandemic has put the world in an uneasy holding pattern, but South Korea’s demographic challenges are unlikely to slow down. The country has a clear, persistent need for an influx of labor. A recent government report projected that South Korea’s population could begin contracting in 2030 and that, by 2067, the country’s working-age population could decrease from 73.2 percent to 45.4 percent of the population. Such seismic shifts will necessitate greater levels of inbound immigration (perhaps millions of workers) to bolster the country’s workforce. So far, the country’s number of inbound immigrants per year has climbed from 137,202 in 2000 to 251,466 in 2018 (see figure 3).

South Korea is experiencing a dramatic taste of this future during the pandemic. South Korean farms are facing an acute labor shortage because the seasonal foreign migrant laborers they depend on are unable to enter the country under pandemic-related restrictions. The government twice provided fifty-day visa extensions for more than l8,000 EPS migrant laborers in the country to cope with these labor shortages in April and July 2020.

While no one could have foreseen the pandemic, it is helping to clarify the limits of South Korea’s reliance on an EPS labor system designed around temporary stays—a system that raises hard questions about who counts in South Korea’s supposedly multicultural society.

South Korea’s global profile is on the rise because of its response to the coronavirus pandemic. But this potential boost for the country’s international standing and soft power is limited by the incongruences between its pro-multicultural soft power brand and the real immigration challenges the country is grappling with, especially amid the pandemic. The image of competence and potential for soft power generated by South Korea’s effective public health response to the pandemic could be squandered if the country continues to struggle with an existential demographic crisis and domestic resistance to the multiculturalism needed to right the ship.

Esther S. Im is a program officer at the National Committee on North Korea. Previously, she was a junior Fulbright researcher in South Korea (2015–2016) and a researcher at the Permanent Mission of the Republic of Korea to the United Nations, where she covered sanctions, nonproliferation, and disarmament issues during South Korea’s term on the Security Council (2013–2015). The views expressed are solely those of the author and not those of any of these entities.

How South Korean Pop Culture Can Be a Source of Soft Power

South Korea’s global cultural clout is no longer in question. This year alone, the world has seen the popular boy band BTS smashing records and snatching awards around the world, the critically acclaimed movie Parasite carving out a space for Korean cinema after becoming the first foreign language film ever to win the top prize at the Oscars, and Korean domination in the production of video games and, increasingly, in the popular e-sports arena.

Now, rather than passively letting K-pop or Korean dramas continue to attract audiences around the world, the South Korean government wants to get actively involved in helping convert the country’s powerful pop culture and other soft resources into true soft power. At various turns, this goal has involved bringing celebrities directly into traditional diplomatic events, enlisting them to record messages of support before major negotiations, and more.

But with this more active stance, South Korean officials must be strategic in how they invoke celebrity power. Right now, this process appears to be somewhat trial and error—randomly inviting celebrities to high-profile political events in hopes of attracting an audience of interested global fans. For South Korea to really tap into the political potential of its pop culture, however, the government needs to be more deliberate in connecting celebrity influence with specific foreign policy goals.

Jumpstarting the Craze

South Korean pop culture’s global takeover has included a vast range of offerings, starting with television dramas, video games, and pop music but now increasingly branching into movies, books, and even sports. This phenomenon is known as the Korean wave, or Hallyu—a term coined in the 1990s as Korean shows began gaining popularity in China. Now Korean cultural exports are pulling in audiences worldwide.

Note: The Case for South Korean Soft Power project and the Korean language course at Middlebury featured in this video were both funded by the Korea Foundation. The foundation had no involvement in the production of this video, the content of this article, or the content of the project as a whole.

As intuitive as pop culture’s appeal is, it is important to make one distinction clear at the outset—being home to popular shows and bands is not in itself a form of soft power. There is a distinction between nation branding—a country generally promoting a positive but relatively shallow view of itself—and soft power. Soft power takes the appeal of soft resources—attractive pop culture fixtures like movie stars and pop icons, tourist attractions, and a welcoming environment for study abroad programs—and combines them to create, and solidify, new long-term changes in how people think about or interact with the country in question. After all, as the father of soft power, Joseph Nye, wrote, soft power is all about getting another party to want what you want.

Luckily for Seoul, the way Korean culture has grown in popularity around the world—with support but not direction from the government—will make it easier for the country to try to convert its deep well of soft power resources into active soft power. South Korean governmental support for the creative industries dates back to the early 1990s. Through policies like encouraging corporate investment and vertical integration in the film industry and slowly removing barriers like screen quotas for foreign content, the South Korean government laid the groundwork. This entailed providing stable financial footing while also encouraging South Korean creatives to innovate and compete with their international counterparts.

These early policies were particularly focused on bolstering the South Korean entertainment industry’s export potential—a governmental report in 1994 famously compared the revenue of the film Jurassic Park to the revenue South Korea could earn from selling 1.5 million Hyundai cars overseas. At times, this government support has been misinterpreted as the South Korean government supposedly creating the wave of popularity that South Korean pop culture has garnered as it has gained prominence all over the world. But it would be more accurate to say that Seoul created an environment in which the movie, television, and music industries were able to thrive.

Harnessing the Korean Wave’s Power

Only later—once starstruck fans in Asia, then in Latin America and the Middle East, and finally around the world got hooked on these South Korean pop culture exports—did the focus shift to the political repercussions of having millions of fans around the world eager to actively engage with Korean culture. The South Korean government does not have to, and indeed would be well-advised not to, get out in front of its pop culture superstars to push a policy agenda. Instead, government officials should work to create links between stars, fans, and foreign policy objectives.

This is easier said than done, however, and something the South Korean government is still figuring out as it transitions from a focus on nation branding to a deeper soft power strategy. When President Moon Jae-in brings famous singers and golf stars to a meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump, or hosts a friendship concert alongside his summit with French President Emmanuel Macron, it is unclear what policy purpose those events serve beyond generally attracting more fans to pay attention to these meetings.

One initiative that was particularly successful—likely because it was clearly attached to a specific policy goal—was when the South Korean government arranged for internationally known singers like Red Velvet and Baek Ji-young to perform at a concert in Pyongyang in honor of the first summit in 2018 between Moon and North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un. The concert attracted fans around the world, not just in South Korea. This kind of event is not about Seoul lecturing foreign audiences on its policies—rather, the South Korean government is tapping into genuine interest among global fans, as clips from the concert racked up a combined 3 million views and counting on YouTube.

The government doesn’t even have to be directly involved (at least at the outset) for South Korean celebrities to keep generating deeper engagement between fans and Korean culture more broadly. Popular singers sometimes feature traditional Korean instruments, architecture, or clothing in their performances and in their daily lives. One small designer selling modernized Korean hanbok (a traditional garment) was inundated with overseas orders after the BTS member Jungkook was spotted shopping for an outfit.

One particularly notable example is the way Big Hit Entertainment and Hankuk University of Foreign Studies jointly created a series of textbooks featuring BTS for international fans to learn Korean. The South Korean government sometimes then takes notice of the potential of these organic projects. In August 2020, the government-affiliated Korea Foundation announced that it was partnering with Big Hit and Hankuk University to sponsor language classes featuring the textbooks at six universities in four countries around the world—including the prestigious Middlebury Language Schools in the United States (see video above).

But this strategy is not foolproof. Besides the aforementioned risk that government-curated appeals to pop culture could seem inauthentic, broad global popularity itself opens up a wider range of complications. As South Korean pop culture has spread around the world, it has also opened up new vulnerabilities that could impact Seoul’s burgeoning soft power. When China was angry at South Korea for installing a U.S. missile defense system, one of the first ways Beijing struck back was by restricting South Korean cultural exports and tourism. Anything South Korean stars do or say—such as waving a Taiwanese flag, supporting Korean claims to islands also claimed by Japan, or even just honoring South Korean and American sacrifices during the Korean War—can turn into foreign policy disputes.

South Korean public diplomacy has at times been able to successfully tap into fan networks and deliver positive, authentic messages to highly interested and engaged audiences. Yet once a message goes online, public diplomats no longer control it—netizens can receive it, interpret it, and even manipulate it as they will.

Riding the Korean Wave

In a way, this is the beauty of South Korean pop culture—communities of fans have united around interests that inspire them to deeply engage with each other and with their favorite singers or actors. Finding ways to tap into this authentic interest among fans, including by creating opportunities for celebrities to use their own voices to speak for South Korean foreign policy priorities such as inter-Korean détente, can be incredibly powerful.

The key will be setting and sticking to deliberate goals—by finding key South Korean foreign policy priorities like trade promotion and development, health security, or even territorial disputes—rather than merely assuming that the presence of a famous Hallyu celebrity at an event will be enough to garner support from fans.

Jenna Gibson is a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago, specializing in international relations. She is a regular contributor to the Korea column for the Diplomat and has also written about Korean social issues and pop culture for other outlets including Foreign Policy and NPR.