Without the transatlantic relationship, former U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger once said, Europe would be at the mercy of China, a mere “appendage” of Eurasia. This bleak notion is weighing heavily on the minds of German officials as they contemplate their country’s place in a world of escalating U.S.-China competition. German Chancellor Angela Merkel referred to Kissinger’s observation in a January 2020 speech, telling an audience in Berlin that it had prompted her to take a “fresh look at the map.” “As Europeans,” she said, “we need to think very hard about how we position ourselves.”

Germany is in the midst of a wrenching reassessment of its relationship with China, a challenge made infinitely more difficult by its increasingly strained ties with the United States. Berlin shares many of Washington’s concerns about Beijing from the lack of reciprocity in its economic relationships with trading partners and the spread of debt and political influence through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to its growing use of surveillance technology and detention of over 1 million Muslims in Xinjiang. But after spearheading a pushback against the policies of Chinese President Xi Jinping, a campaign that culminated last spring when the EU declared China a “systemic rival,” Europe’s largest member state is wavering, keenly aware of its own vulnerabilities and wary, despite its concerns about China’s political and economic development, of following Washington down a path toward full-blown confrontation with Beijing.

Germany’s challenge in 2020 is to define a third space for itself and for Europe in the face of this growing U.S.-China discord. But the Merkel government’s reluctance to antagonize Beijing risks undermining the EU’s push for a common policy toward China and perpetuating a situation where member states look out for their own interests, often to the detriment of a common European front. A desire to minimize the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic across Europe is likely to reinforce the temptation to keep Beijing close.

The Wake-up Call

For decades, Berlin’s strategy toward Beijing was defined by the phrase “Wandel durch Handel,” or change through trade. Like other Western democracies, including the United States, Germany convinced itself that China’s authoritarian politics would morph into a free, open, and more democratic system through ever-tightening economic ties. This allowed German companies to double down on the vast Chinese market, investing billions of euros in new factories. A rapidly modernizing China, meanwhile, could not get enough of Germany’s machine tools and manufacturing know-how. In 2001, when China became a member of the World Trade Organization, Merkel’s predecessor Gerhard Schröder was one of Beijing’s most enthusiastic supporters. Because German firms were making unprecedented profits in China, their executives discouraged German policymakers from complaining about the myriad problems tied to doing business there, such as forced technology transfers, intellectual property theft, and protectionist barriers to investment. During the global financial crisis and the eurozone unrest that followed, Germany’s close links with China’s growing economy helped it weather the storm. Top aides to the chancellor, when asked about her views on China, stress that she has not forgotten the supportive role China played during this time of existential turmoil for Europe.1 In private, she has expressed admiration for the Chinese Communist Party’s success in lifting millions out of poverty.

When Xi came to power in 2012, Europe’s leaders were still very much preoccupied with their own troubles. China’s controversial 16+1 forum with Central and Eastern European countries (launched the same year), the BRI (unveiled in 2013), and the Made in China 2025 strategy—a blueprint for Chinese domination of ten key emerging technologies announced in 2015—did not cause a big stir in Berlin when they were first unveiled.

In 2016, however, Germany experienced what senior officials now acknowledge was a wake-up moment. The trigger was not Xi’s growing crackdown on political dissidents at home, but rather a $5 billion offer, announced in May of that year, by China’s Midea Group for Kuka, a German robotics manufacturer. The bid for a company some saw as a crown jewel of German industry caught the government off guard. With no obvious legal options to block the takeover, it scrambled to find another suitor. But no German or European company was prepared to top Midea’s hefty offer, and Kuka fell into Chinese hands. Months after the Kuka surprise, the Obama administration forced Germany to withdraw its approval for a Chinese takeover of Aixtron. The German chip maker’s technology, it turned out, was being used to upgrade U.S. and foreign-owned Patriot missile defense systems.

That Berlin gave the Aixtron takeover a green light exposed the inadequacies of its own defenses, and a sense of panic began to set in. As the Kuka and Aixtron cases suggest, Germany’s concerns about China were driven by economic, rather than political, considerations. Chinese companies had moved up the value chain much faster than expected, developing into major competitors to German industry leaders. At the same time, business conditions in China were becoming more difficult as Xi pushed for greater state control over the economy. German businesses, rather than discouraging politicians in Berlin from pushing back, as they had once done, began demanding action against Beijing. China’s buying spree in Europe, part of the drive to deliver on Xi’s grand industrial policy plan, was what finally spurred German politicians to act. It also forced them to confront other concerns about China that went beyond the economic sphere.

The Pushback

In the ensuing months, the German government scrambled to rework its own foreign investment rules, reducing the threshold for intervening to block acquisitions. In 2017, it joined France and Italy in asking the European Commission to look into an EU-wide investment screening mechanism. Chinese foreign direct investment in Europe peaked at 37 billion euros in 2016. It has declined every year since then—a trend driven by Chinese capital controls as well as Europe’s tougher defenses. But the sense in Germany that Chinese investment was now a threat, rather than an opportunity, had taken hold.

Sigmar Gabriel, who as economy minister had overseen Germany’s response to the Kuka and Aixtron bids, became foreign minister in January 2017 and introduced regular interministerial meetings on China. Although concerns about Chinese acquisitions and German industrial competitiveness had triggered pushback against China, some German officials argued the government needed to take a closer look at the broad range of Chinese activities in Germany. They worried that ministries in Berlin, as well as regional governments in Germany’s sixteen länder, or federal states, lacked awareness about the risks associated with these activities. Local politicians were striking deals with Chinese companies, and the central government was either in the dark or powerless to stop them.

The western city of Duisburg, hailed by Mayor Sören Link as “China’s gateway to Europe,” was the most glaring example. In the span of a few years, the city had evolved into a European hub of Xi’s plans for a connected Eurasia through the BRI, becoming the prime destination for Chinese goods entering the continent by train. The University of Duisburg-Essen, home to a leading Confucius Institute, attracted more Chinese students than anywhere else in Germany. In 2018, Link led a nineteen-strong delegation to Huawei’s headquarters in Shenzhen, announcing plans to turn Duisburg into a smart city powered by Chinese 5G technology. While China hawks in the foreign ministry saw the flurry of Chinese activity in Duisburg and other parts of Germany as a problem, others, including Merkel and some of her conservative allies, were reluctant to broaden the policy response beyond narrow investment restrictions. “Merkel has no problem with pushback against China as long as it’s not Germany that is doing the pushing,” a senior German official said.2

In January 2019, the influential Federation of German Industries (BDI), which had soft-pedaled criticism of China for years out of fear that its members could become targets of Chinese reprisals, shifted gears and published a sharply critical report. It described China as a “systemic competitor” and dismissed the idea that the country was evolving toward a more open, liberal governance model. The report was even more surprising since it followed a series of strategic concessions the Chinese government had made to companies like BASF, BMW, and Allianz. These concessions were meant to silence European grumbling about Xi’s failure to deliver on his promises, made at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2017, to open up China’s market. Instead, the BDI urged a forceful, collective European response to China, a significant departure from its previous emphasis on strong bilateral ties between Berlin and Beijing. The BDI did not limit itself to criticism of business conditions for German firms but also expressed broader concerns about increased state control and surveillance under Xi.

“No one should simply ignore the challenges China poses to the EU and Germany,” BDI President Dieter Kempf said at the time. German industry leaders, among the biggest beneficiaries of China’s economic rise, had leapfrogged the political establishment in criticizing China’s political development, or lack thereof. The BDI was saying what a growing number of German companies were feeling but were afraid to say themselves. Chief among them were Germany’s big carmakers, Volkswagen, Daimler, and BMW, which make roughly one-third or more of their profits in China, according to industry experts. Less than a year before the BDI report came out, Daimler had been forced into a humiliating apology over a Mercedez-Benz Instagram ad that included an innocuous quote from the Dalai Lama—the Tibetan spiritual leader whom Beijing views as a separatist. The post was hastily deleted, and the company’s chairman at the time, Dieter Zetsche, wrote a letter expressing deep regret for the “hurt and grief” his company’s “negligent and insensitive mistake” had caused the Chinese people.

Two months after the BDI report, the European Commission upped the ante with a strategy paper that described China as a “systemic rival” in certain areas (it also called China a “partner” and “competitor” in other domains) and urged a rethink of Europe’s industrial, competition, and procurement policies to shield it from unfair Chinese competition. French President Emmanuel Macron, declaring the end of an era of European naivety toward China, invited Merkel and then European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker to Paris when Xi visited him in March 2019. His message was clear: from now on, Europe would speak with one voice when dealing with China.

One year on, however, the momentum behind a tougher, united European approach to China has stalled, and some officials in Brussels, Paris, and other capitals are putting the blame on Germany.3 A new European Commission led by former German defense minister Ursula von der Leyen has continued to hold a firm line, warning member states about the risks tied to Chinese 5G suppliers and developing plans to address distortions in competition arising from state-supported Chinese companies. But the ever-cautious Merkel has been pressing the brakes, worried the pushback against China could go too far. Her approach, driven by a dual desire to protect German economic interests and hedge against U.S. President Donald Trump’s unpredictability, has not gone unnoticed in other European capitals. Merkel’s government has shown that it is not prepared to lead Europe toward a more robust, collective approach toward China, especially if that means Germany must pay an economic price.

The Retreat

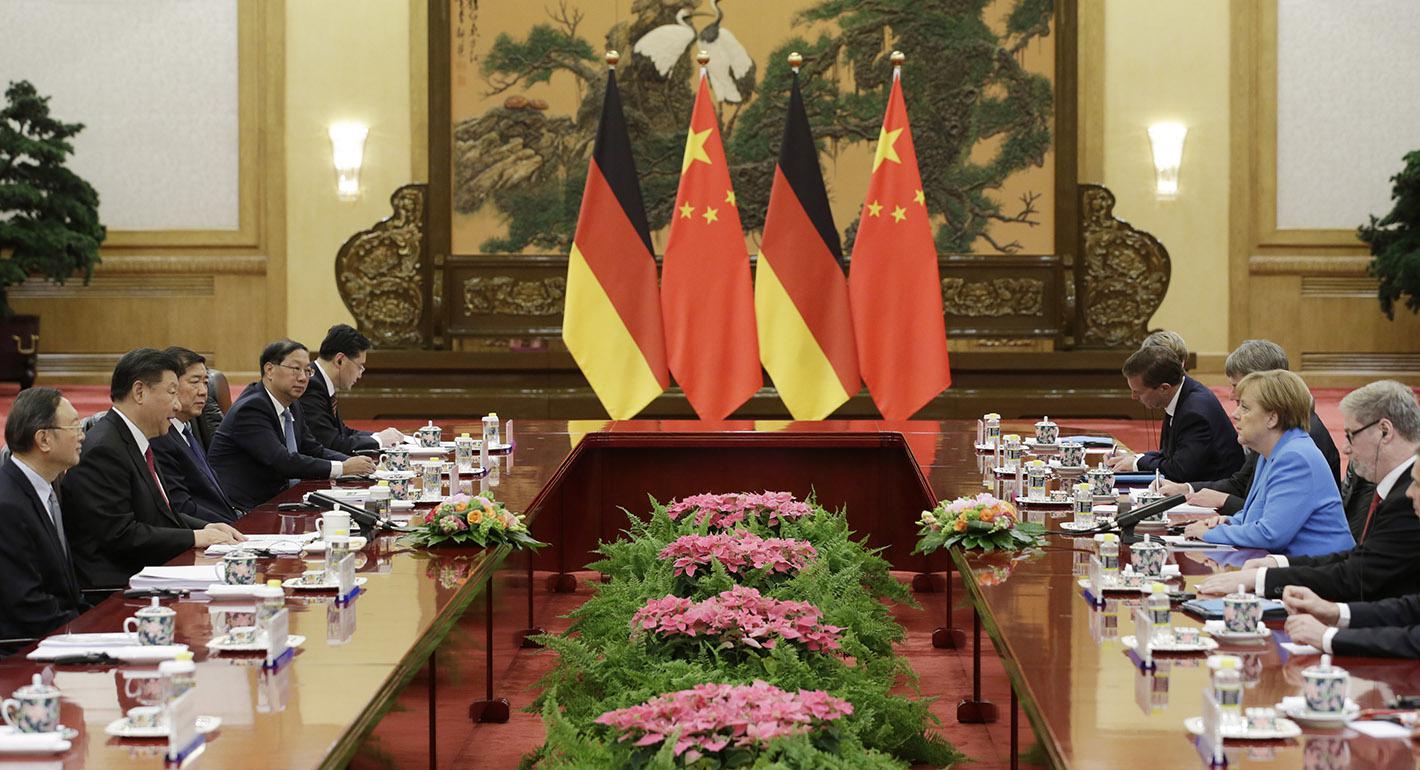

Over the past half year, Merkel has studiously avoided confronting China on a range of issues. Last September, on her twelfth trip to China in fourteen years as chancellor, Merkel brought a large delegation of German business executives with her, sending a back-to-business message at a time when pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong were raging and new revelations about Chinese suppression in Xinjiang were emerging. She has pushed back against a broad front of German lawmakers, including many in her own party, who view Chinese telecommunications group Huawei as a security risk and want to exclude it from Germany’s 5G network. In January 2020, out of concern that it would offend Beijing, she broke with London and Paris in refusing to publicly congratulate Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen on her reelection.

Her hope, it seems, is that German restraint will encourage Beijing to make concessions at what will be the signature event of Merkel’s final term as chancellor—a summit with Xi in the eastern city of Leipzig. The meeting will bring together China’s president and the leaders of all twenty-seven EU member states for the first time. Merkel’s goals for the summit include clinching an elusive investment treaty between the EU and China, as well as forging closer cooperation on climate change and African development. The larger format, German officials involved in the planning have said, is meant to demonstrate EU unity in dealing with Beijing.4 But it is unclear how a meeting between EU leaders and Xi will bring Europe closer to a common China policy.

Some European officials worry it may end up sending a very different message two months before the U.S. presidential election: one of EU-China unity. At a time when competition with China is becoming the organizing principle of U.S. foreign policy, Germany is spearheading a European push to deepen cooperation with Beijing, giving Xi another opportunity to show he is serious about opening up the Chinese market and cooperating with the West on areas of common interest. At a time when Europe has defined the relationship with China on three separate levels—partner, competitor, and rival—Berlin sees the Leipzig summit as an opportunity to underpin the partner side of the relationship with substantial agreements. This, Merkel hopes, will ensure that ties do not become defined by competition and rivalry.

Roughly six months before the summit, however, German and European officials see a significant risk that neither the investment agreement nor the climate change and Africa initiatives will come to anything. China has shown few signs that it is prepared to make the concessions that Germany and the EU are seeking. Furthermore, the coronavirus pandemic could further hamper the prospects for a deal by reducing face-to-face contact between the two sides in the months to come. Already, it has led to the postponement of an EU-China meeting in late March that was meant to prepare the groundwork for Leipzig. If the two sides fail to clinch a substantial deal, the pictures of Xi and European leaders gathering in Germany two months before the U.S. election will be the main message. For China, in the midst of an aggressive propaganda campaign to shift blame for the virus to Washington and present itself as a friend of Europe, that alone would be considered a success. But for Germany, failure would give way to a bigger question: how to proceed with China when it is clear that Xi is unwilling to deliver on his promised reforms?

That challenge may fall to Merkel’s successor. It is too early to say who that will be, but a leadership contest within her Christian Democratic Union (CDU) could prove decisive for Germany’s future stance on China. Armin Laschet, the premier of North Rhine–Westphalia and the frontrunner to lead the party, supports deeper economic ties with China and appears open to working with authoritarians like Xi. Were he to emerge victorious and replace Merkel as chancellor in 2021, Germany’s strategic ambiguity would surely continue.

However, if one of his two conservative rivals in the CDU, Friedrich Merz or Norbert Röttgen, were to come out on top, or if the Greens party were to take over the German chancellery in a future government, one would expect a tougher line on China. The Greens have been more outspoken than any German party on the Muslim internment camps in Xinjiang and the risks stemming from Chinese surveillance—issues that should be anathema to a country that experienced the ethnic crimes of the Nazis and the domestic spying excesses of the Stasi.

Public opinion surveys suggest Germans, like their government, would prefer not to take sides in the clash between Washington and Beijing. In a September 2019 poll published by the European Council on Foreign Relations, Germans were asked whose side their country should take in a conflict between the United States and China. Some 73 percent said Germany should remain neutral, 6 percent favored China, while just 10 percent said they should side with the United States—far below the levels reported in France, Italy, Spain, and large countries in Eastern and Northern Europe. A Bertelsmann survey published in January 2020 showed that 32 percent of Germans see China as a partner for Europe, nearly double the level in France. Finally, a Pew Global Attitudes survey from the spring of 2019 found that 34 percent of Germans had a favorable image of China, compared to 39 percent for the United States. The gap of five percentage points was one of the lowest in Europe. It compared to gaps of fifteen points in France, nineteen points in the UK, and twenty-five points in Italy.

“Rolling Our Way”

Amid the strategic uncertainty emanating from the chancellery in Berlin, some politicians and businessmen are seizing the initiative to prevent the Germany-China relationship from veering off track. In January, Hans-Peter Friedrich, a member of Merkel’s Bavarian sister party and a vice president of the Bundestag (the lower house of parliament), announced the formation of a new group aimed at fostering dialogue and cooperation with China. The China-Brücke, or China-Bridge, is modeled on the Atlantik-Brücke, a group founded in the decade after World War II to foster transatlantic relations, and which is now led by former foreign and economy minister Gabriel. Executives from German companies like SAP and Chinese firms including Alibaba, ZTE, and Huawei are said to be playing supportive roles behind the scenes.

The start of 2020 also brought news that German prosecutors are investigating a former top EU diplomat, Gerhard Sabathil, on suspicions of spying for China’s intelligence service. Sabathil, who had been working as a lobbyist in Berlin after having his security clearance revoked during a posting in South Korea and subsequently leaving the EU’s diplomatic service, has close ties to Merkel’s CDU party. Officials in Berlin and Brussels say he was protected by politicians in the party for years.5

Friedrich and Sabathil are not representative of the German mainstream, but their cases show that there are still those in Germany who see China as more of an opportunity than a risk. The BDI paper and the Röttgen-led revolt against Merkel’s Huawei-friendly 5G policy attest to a growing backlash against these “China Versteher,” or friends of Beijing. But the lack of a clear line from Merkel’s government has given pro-Beijing voices space in the political debate. It is unclear how these tensions will be resolved.

Indeed, with nothing to replace “Wandel durch Handel,” Germany finds itself in a strategic gray zone with China, aware that its largest trading partner is evolving into a bigger and brasher threat, but unwilling to test the relationship in any serious way. The strength of Germany’s economic ties to China are one reason for this. Others include anxiety over Berlin’s future relationship with Washington, uncertainty over the future of NATO, and the lingering threat of trade tensions with Trump. The coronavirus crisis, although it originated in China, has not made it easier for Berlin to side with Washington. While Trump introduced a travel ban on European countries and blamed them for failing to contain the virus, China has built a feel-good public relations campaign around sending medical equipment to countries like Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands.

The last thing Germany wants is for Europe to become an “appendage” of China, as Kissinger suggested. But neither does it feel that it, or the EU, can afford to fight the giant at its doorstep. “We are on the same land mass as China,” a senior German diplomat remarked, pointing to a large map on the wall. “China has a vision. They are rolling our way, reaching out. Do we want to take their hand? That isn’t clear yet.”6

Noah Barkin is a senior visiting fellow at the German Marshall Fund.

Notes

1 Author interviews with top Merkel aides, August 2019 and January 2020, Berlin.

2 Author interview with a senior German official, January 2020, Berlin.

3 Author interviews with various European officials, November and December 2019 as well as January 2020, Brussels and Berlin.

4 Author interviews with German officials, December 2019 and January 2020, Berlin.

5 Author interviews with European officials, January and February 2020, Berlin and Brussels.

6 Author interview with senior German diplomat, January 2020, Berlin.