During his second term, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki emerged as a dominant player in Iraq’s political landscape. A weak legal framework and divisions among the prime minister’s opponents helped facilitate his rise to power. But above all, control of the Iraqi security apparatus and army was key. The struggle to consolidate power has created a climate of continuous political crisis that can only be overcome by the efforts of all political groups to establish effective political leadership and strengthen Iraq’s legal framework.

Key Themes

- The deployment of the army throughout Iraq enabled the prime minister to strengthen his political power base in Baghdad. As the only institution present throughout all the provinces (except for the territory of the Kurdistan Regional Government), the army has allowed Maliki to assert the central government’s authority over much of Iraq.

- Several attempts were made in 2012 to unseat the prime minister, but Maliki’s power remains difficult to challenge. His opponents have failed to form a unified front.

- The Kurds possess their own security forces—the peshmerga—and the region of Kurdistan is exclusively controlled by those forces. They have been engaged with the prime minister in a military standoff.

- The prime minister’s power consolidation remains contested. The end of 2012 saw a wave of antigovernment protests in the Sunni-majority provinces and rising tensions between the Kurds and the central government over the disputed territories.

Policy Recommendations for Iraq’s Political Groups

Invest in bolstering Iraq’s legal apparatus and state institutions. All political groups should refrain from using security forces to conduct a political struggle. Building up Iraq’s legal framework and institutions will help the country avoid the continuous cycle of political crisis.

Strengthen ties with Iraqi citizens. Political groups should reach out to the segments of society that feel disenfranchised by the government and poorly represented by the opposition.

Work together to build a more inclusive government. Consolidating power through policies that exclude certain segments of society affects Iraq’s stability. For the country to become stable, its main political groups should have a genuine stake in governing.

A Rise to Dominance

Nouri al-Maliki was appointed to a second term as Iraqi prime minister in December 2010 and has since emerged as a dominant player in Iraq’s domestic political scene. Influence over the army in particular has allowed the prime minister to bolster his power within his own Shia coalition, nurture alliances with some of the Sunni groups, and engage in a standoff with the Kurds.

Several attempts were made in 2012 to unseat the prime minister, but all have come to naught. His political moves and influence over the armed forces, combined with the divisions among his opponents, have solidified his rise.

Political Dynamics

In the immediate aftermath of the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, Iraqis sought to establish a new constitutional framework that would guarantee a more equal distribution of power and ensure a democratic transition. The country’s new constitution, ratified in 2005, envisioned a parliamentary system that would include numerous political parties and transform the country into a decentralized state in which Baghdad and the provinces shared governing powers.

The Iraqi constitutional and legal framework is still flawed.

The new legal framework redistributed power among Iraq’s political players, but it failed to regulate the exercise of that authority. An array of political parties participated in the legislative elections of 2005 and 2010 as well as in the provincial elections of 2009, and new political leaders were empowered in parliament and the provincial councils.

The autonomy of Iraqi Kurdistan in the northern part of the country was consolidated, and the other provinces were granted some authority over their own security, budgets, development projects, and public services. However, the Iraqi constitutional and legal framework is still flawed. According to the constitution, many state activities are to be regulated by national legislation, but many of those laws remain unissued.1

Four main coalitions competed in the March 2010 elections, Iraq’s most recent: the Sunni-dominated Iraqiyya; Maliki’s Shia State of Law coalition; the Iraqi National Alliance, which included the other main Shia groups, Moqtada al-Sadr’s Sadrist Trend, and the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq; and the Kurdistan Alliance of Kurdish President Masoud Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party and Iraqi President Jalal Talabani’s Patriotic Union of Kurdistan.

Iraqiyya narrowly won a plurality, securing 91 of 325 seats in the parliament, while the State of Law coalition finished second with 89 seats. In order to overtake Iraqiyya’s parliamentary majority, Maliki had to join forces with the other Shia groups of the National Alliance, in particular the powerful Sadrist Trend, which controlled 40 of the 71 seats won by the National Alliance. The Kurdistan Alliance, meanwhile, secured 43 seats for its list.

In attempting to form a government following the 2010 elections, the country’s leaders—Ayad Allawi of Iraqiyya, Maliki, and the leaders of the Kurdistan Alliance—plunged Iraq into a nine-month deadlock while they fought for control of ministerial portfolios. Factionalism and internal competition plagued these main political blocs. Iraqiyya in particular competed in the elections as one list but in fact had multiple factions and leaders: Allawi, Osama Nujeifi, Tariq al-Hashemi, and Saleh al-Mutlaq. These leaders remained largely disconnected from local officials and their constituents in the provinces.2

The struggle ended with the formation of a new government headed by Maliki in December 2010, but Maliki was appointed premier only by agreeing to share executive powers with Iraqiyya and at least acknowledge Kurdish claims to long-disputed territories on Kurdistan’s frontiers. Moreover, according to the deal among Iraq’s political forces, control over national security would be divided, with the security ministries split between Iraqiyya, whose candidate would be assigned the Ministry of Defense, and State of Law, which would get the Ministry of Interior. A National Council for Strategic Policy would be established and headed by Allawi. But Iraq’s political scene remained deeply divided, and the promised conciliation and power sharing never took place.

Consolidation of Power

Throughout 2011, Maliki was able to consolidate his power and emerge as the dominant player in Iraqi politics.

Opponents charge that the prime minister backed away from the powersharing agreements he had forged with Iraqiyya and the Kurds. Indeed, Maliki employed an expansive interpretation of the powers granted to the prime minister by the constitution, in particular “the naming of the Cabinet’s members” (Article 76), taking charge of both the formation of the cabinet and the appointment of strategic ministries. In addition, the central government’s influence in the provinces—where all Iraq’s political groups have their electoral strongholds—allowed the prime minister to strengthen allies, weaken local rivals, and tip the scales of parliamentary power in his favor.

Checks and balances on the prime minister’s power could in theory come from other branches of the government, but the dynamics of power politics have also impacted Iraq’s constitutional framework.3 By 2012, the cabinet had strengthened its capacity to oversee the functions of other institutions. Bodies that were at one time independent have been affected, including the Central Bank, Independent High Electoral Commission, Commission of Integrity, and the High Commission for Human Rights. Meanwhile, Iraq’s parliament has been weakened, both in terms of its legislative function and its ability to check the power of the cabinet.

Power consolidation has not simply been the result of the prime minister’s policies and the weaknesses of Iraq’s legal and political system. It has also been enabled by the divisions among Maliki’s opponents. In 2011, the Iraqiyya list lost its grip on the provinces in which it had won provincial council elections, and the list also split at the national level. Its parliamentarians were disunited and often unable to protect the rights of their provincial officials.

Iraqiyya defectors have provided Maliki with Sunni allies in his otherwise predominantly Shia alliance structure.

As a result, Iraqiyya’s local officials grew skeptical of their parliamentary representatives’ capacity to maintain security, honor budget commitments, guarantee basic services, and implement projects. In some cases, the local officials decided to approach Maliki directly, entirely bypassing their own list in the process. Even Iraqiyya’s national officials, eager to maintain their posts in the face of the prime minister’s growing power, distanced themselves from the list as disfavor with the party mounted. In March 2011, ten of Iraqiyya’s deputies split from the list, forming a splinter group called “White Iraqiyya.” Desertion only increased as the year wore on. Iraqiyya defectors have provided Maliki with Sunni allies in his predominantly Shia alliance structure.

Within the Shia camp, the power balance shifted toward Maliki’s coalition. The prime minister’s rivals steadily lost influence. The Sadrist Trend found itself increasingly unable to deliver services in the provinces where it held sway, and the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq split, with eight of its deputies supporting the prime minister’s State of Law coalition.

The Kurdish political forces were the only political group to hold on to some key cabinet posts, including deputy prime minister, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the trade minister, and the Ministry of Health, in addition to the presidency of Jalal Talabani. Kurds remain the most significant counterbalance to the prime minister’s dominance; beyond these posts, they maintain an autonomous region with its own government and security provided exclusively by Kurdish peshmerga forces.

The Army and Consolidation of Power

Despite all of this political maneuvering, the deployment of the army proved to be the key precondition for political consolidation, for the army was the only institution present throughout all the non-Kurdish provinces and invested with the force of arms.

The army has played a central role in Iraqi politics throughout the country’s modern history. In 1958, army officers seized control of the country through a military coup, founding the Republic of Iraq. Army officers organized the country as a modern state, established national institutions and a bureaucratic framework, and planned Iraq’s economy.4

In the late 1970s, Saddam Hussein, a nonmilitary man who rose through the Baath Party ranks, asserted his power by marginalizing and establishing control over the army leadership.5 By controlling the army, Saddam Hussein was able not only to remain in power for more than twenty years (1979–2003) but also to rule his country with an iron fist and maintain an aggressive regional foreign policy.6

Following the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, the Iraqi army was disbanded, and the Americans heavily invested in rebuilding a new army that would supposedly be the guardian of a democratic order. This army was intended to be a professional force that reflected the country’s ethnic and sectarian composition—Shia, Sunni, and Kurd. And as part of the democratic transition it sought to engineer in Iraq, the United States introduced the principle of civilian control over the military.

As Major General Paul Eaton, the commanding general of the Coalition Military Assistance Training Team from 2003 to 2004, said in an interview, “Since 2003 the focus was to give the new Iraqi army an officers’ leadership which would be under a civilian chain of command.” De-Baathification policies were put in place to marginalize the army’s past leadership and promote the emergence of a new senior officer corps educated under the U.S. occupation.7

Iraq’s leaders have competed for control of army divisions as a way to increase their shares of power and expand their territorial reach domestically.

During the years of the U.S. occupation in Iraq, civilian control of the army, de-Baathification, and ethnic and sectarian quotas—policies that were all implemented while Iraq’s leaders were locked in a power struggle and the country’s legal framework was weak and incomplete—laid the groundwork for the emergence of a politicized army.

Moreover, the newly formed Iraqi army, confronted with increasing security challenges, deployed within the country’s border as an internal security force.8 But invested with this new role, the army soon became a tool in the country’s internal power struggle. Iraq’s leaders have competed for control of army divisions as a way to increase their shares of power and expand their territorial reach domestically.

De-Baathification policies created discontent among officers, which made it easier for Iraq’s leaders to secure their loyalty through promotions and appointments, especially those who had been demoted or forbidden to enter the new army.9 Furthermore, in the chaotic political environment, army officers had to establish ties to the new political parties. Those ties generally formed along sectarian and ethnic lines, as that was the only way to access jobs or promotions within the new army.

In the words of an Iraqi officer in charge of the Coalition Military Assistance Training Team recruitment section in 2004, “It was hard on the pride of those former officers who were downgraded: captains did not want to come back to be lieutenants. In order to get back their rank, they had to form an allegiance with one of the parties dominating the . . . [Ministry of Defense] and fill one of the ethnic and sectarian quotas.”10

In his effort to consolidate power, Prime Minister Maliki prioritized the army. He built bridges with a circle of high-ranking officers during his first term in office by issuing the Justice and Accountability Law (2008) that reversed de-Baathification policies and allowed officers who had been excluded or downgraded to enter the new army while keeping their ranks or to again have the chance to be promoted.

After Maliki’s reappointment in 2010, the portfolios of defense and interior remained unfilled, but the prime minister effectively occupied both of those positions as acting minister. As commander in chief and acting minister of defense, he acquired the legitimate authority to oversee the army’s entire strategic decisionmaking process and guide its national security strategy. For instance, he supervises the Operations Commands, which are in charge of directing army divisions within the provinces, as well as the army divisions themselves, and he acquired the role of supervising the Ministry of Interior–run police forces within each of the provinces.11 The ministerial positions provide the upper hand over army officers’ promotions to the highest ranks, disqualifications, and appointments to sensitive posts such as operations commander.12

Within a few months of his reappointment, the prime minister could rely on the army to fortify his power in Iraq’s federal and provincial governments. He held the legitimate authority to command the army, and the force’s leadership was broadly aligned with him.

Extending the Army’s Reach

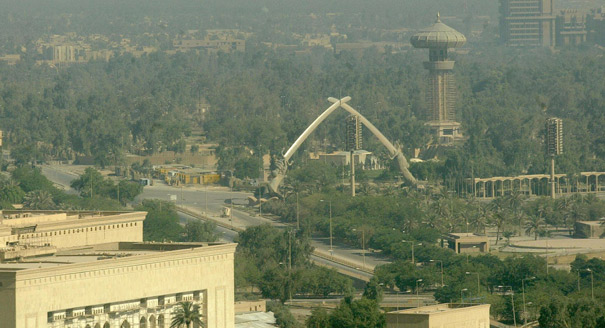

At present, the Iraqi security forces employ about 800,000 individuals. The army on its own is composed of sixteen armed divisions (the Ministry of Defense employs about 270,000 individuals), and has the ability to deploy in all the country’s provinces except for the Kurdish governorates in the north.13 Upon the withdrawal of U.S. forces at the end of 2011, the army assumed complete responsibility for internal security, and it has maintained this role throughout 2012.

The army is the only central government institution that is physically present within the provinces while remaining outside of the provincial governments’ jurisdiction. Provincial officials have no say over the army divisions deployed on their soil, as laid out in the Law of Governorates Not Incorporated Into a Region (Law 21, Article 31, tenth clause). Regardless of where the force is deployed, it has the highest command prerogative in security affairs and supersedes provincial officials and their affiliated police forces.

The presence of the army helped extend the influence of the Ministry of Interior over provincial police and security forces. Law 21 gives local authorities some power to appoint and remove their police chiefs (Article 7, ninth clause), to make some decisions about the operation of police forces, and to approve security plans (Article 7, tenth clause). But with the dominant presence of the army, many local officials have felt pressured to defer to the army and to the central government’s wishes over provincial security decisions.14

Of all the services provided by the federal government, security is the necessary condition that enables the provision of all others, such as electricity, infrastructure, and other public goods. With the ability to increase or decrease security in each province, the army has given Baghdad the upper hand over the provincial branches of government. The provinces that saw their authority over their security dossier decrease have lost authority altogether, from budget allocation and project implementation to investment decisions.

The exception here is the Kurdistan region and some of its bordering territories. The Kurdish peshmerga forces, which are estimated to number at least 190,000, remain under the authority of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The peshmerga mainly respond to the two Kurdistan Alliance parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. In addition to securing the KRG’s provinces, peshmerga forces are deployed in territories that have long been contested by both the KRG and Baghdad.

The Army in the Northern Provinces

The northern and Sunni-dominated provinces in which Iraqiyya had secured an electoral majority—Anbar, Ninewa, Salaheddine, and Diyala—have been prime areas where the central government has attempted to assert its authority. In order to confront any security challenges, the central government had assigned each of these provinces both an Operations Command and an army division by 2011.15

Throughout 2011, Operations Commands increased their control over the management of provincial security. Provincial officials denounced their increasingly limited authority over security matters and police forces, often leading to the replacement of the police leadership. In some cases, the provinces have received fewer federal services and their budget allocations have shrunk. Project implementation in certain provinces has also ceased and investments have dried up as a result of the delayed approval from the central government agencies.

For instance, in May 2011, Anbar provincial council member Faisal al-Issawi stated that interference of the operations commander in Anbar Province marginalized the governor in security matters, led to the dismissal of local officials, and made it more difficult to secure the approval of projects and investments within the province.16 Throughout 2011, Anbar local officials repeatedly asked for the withdrawal of the army and the transfer of the security file to the province, and they denounced the delays in the approval of a gas investment project.17

These provinces have also become vulnerable to decisions made by the federal government’s executive and judiciary bodies. Provincial officials have become increasingly reliant on Baghdad to ensure security and stability for their constituents and to keep them in their posts.18

Iraqiyya’s leaders—Allawi, Nujeifi, Hashemi, and Mutlaq—were unable to obstruct the central government’s policies in these provinces. Local officials progressively disengaged from the Iraqiyya list, which had no central government posts that could regulate security and had lost legitimacy within its electoral strongholds. In October 2011, in an attempt to counter central government policies in the provinces, officials in Anbar, Salaheddine, and Diyala went so far as to demand that they be allowed to form autonomous regions.

Provincial officials have become increasingly reliant on Baghdad to ensure security and stability for their constituents and to keep them in their posts.

Some provincial officials and local authorities decided to deal directly with Baghdad, working around their national list. The negotiations with the central government helped the local leaders to hold onto their posts and overcome challenges in security management, and helped the prime minister establish alliances with local leaders and tribal members.

The government strengthened its local alliances through concessions over the de-Baathification measures. For instance, in July 2012, the Ministry of Defense demonstrated the intent to reintegrate thousands of officers that had been barred from the army and police. This reintegration also extended to members of the Sahwa militia, a tribal-based militia established by U.S. forces to improve security in the provinces of Anbar, Diyala, and Salaheddine.19 As of the end of 2012, and several months before the provincial elections (which will take place in April 2013), Prime Minister Maliki could count on alliances throughout Anbar, Ninewa, Salaheddine, and Diyala Provinces.

But just when his ties with the Sunni leaders had begun to improve, the arrest of some of the guards of the Sunni leader Rafi al-Issawi on December 19 unleashed a wave of protests throughout these provinces. Protesters voiced their discontent with the government’s tight security and, among other demands, called for the release of prisoners and even the exit of the army from the province. However, protests remain so far only partially supported by local leaders, who are split between supporting and opposing the prime minister. Most importantly, mobilization in the provinces remains disconnected from Iraqiyya national leaders in Baghdad. Those leading the demonstrations in Anbar called for direct negotiation with the prime minister without any mediation from Iraqiyya leaders. Anbar’s demonstrators went so far as to threaten Iraqiyya leader Saleh al-Mutlaq physically while he was attempting to give a speech in the province.

Much will depend on the government’s ability to deal with the demonstrations. Indeed, these remain the provinces with the highest number of troops on their soil, and the troops are crucial in pressuring locals to accept Baghdad’s authority in the provinces. But the army’s violent repression of demonstrations can only lead to an escalation of events. On January 25, as clashes erupted between soldiers and demonstrators in Falluja (Anbar), the government eventually had to agree to withdraw its troops from the city.

The Army in the Southern Provinces

Much as it did in the northern governorates, the army’s role grew rapidly over the course of 2011 in some of the Shia-dominated provinces in the south country. This put a new force at odds with the local police over the management of security.

Southeast Maysan Province, for instance, was the site of a confrontation between the Sadrist Trend and the central government. Since the movement laid down its weapons and participated in provincial and legislative elections in 2009 and 2010, respectively, the Sadrist Trend has become more popular in Iraq and an essential ally in ensuring the formation of the incumbent government.

But at the end of 2010, the Sadrists established a stronghold in Maysan Province, replacing the incumbent governor, from State of Law, with a Sadrist who took charge of the province’s security affairs, including deciding whom to appoint police chief.20 However, the central government still controlled the management of provincial security, which, along with the presence of the army, limited the Sadrists’ grip on the province. In 2011, only through the pressure of the army’s Tenth Division, the governor eventually accepted the replacement of Maysan’s police chief with one in line with Baghdad’s orders. Although security remains under the shared management of the local Sadrist authorities and the central government, several visits by the Ministry of Defense have reaffirmed the leading role of the army in the management of security.21

In those provinces where the central government was mostly in control but wished to consolidate its leadership, the police were eventually left in charge of security and encouraged to cooperate with the army divisions. For instance, after the police chief in Basra was repeatedly replaced throughout 2011, police and army leadership began increasingly cooperating to plan a common security strategy.22 These developments have resulted in the consolidation of the prime minister’s power within the southern provinces (Basra, Dhi Qar, Muthanna) at the expense of the other Shia political groups and the Sadrists in particular. As of December 2012 the Sadrists had given their support to the protesters’ demands in the northern provinces, sent a delegation to Anbar and Diyala provinces to listen to the demonstrators’ demands, and strongly denounced the army’s behavior during the demonstrations in Falluja.

The Army in the Disputed Territories

The Kurdistan Regional Government provinces of Dohuk, Erbil, and Sulaymanya have remained outside the Iraqi army’s reach and under the exclusive authority of the Kurdish peshmerga. Kurdish peshmerga are also deployed in disputed territories in the provinces of Ninewa, Kirkuk, Diyala, and Salaheddine, which border the KRG region and have long been contested by the Kurds and the central government in Baghdad. Both Kurdish forces—peshmerga and police—and Iraqi army divisions are now deployed in these territories.

he Iraqiyya list did well in these contested provinces in the 2010 elections but lost popularity in 2011 as it proved unable to represent the demands of its constituents in Baghdad and curb the Kurdish presence in these territories. As 2012 began, the prime minister appealed directly to Sunni Arab groups in these provinces, presenting himself as an Iraqi nationalist leader protecting Iraqi unity against Kurdish separatism and as an Arab nationalist protecting Arab interests against Kurdish expansionism.

Kirkuk, a city long contested by the Kurds and the central government, is a prime example of the tension between the Kurds and the central government. Iraqiyya has electoral pull among the city’s Arab and Turkmen populations, but the KRG has always attempted to establish its authority over the city. It has campaigned for the implementation of Article 140 of the Iraqi constitution, which allows the disputed territories the chance to become part of the KRG region through referendum.

Throughout 2011, the army’s Twelfth Division remained outside Kirkuk while the Kurds increased their presence in the city, deploying their peshmerga forces along the outskirts of the city and expanding their presence within the Kirkuk police force. Much as he has in other Sunni areas of the country, the prime minister has been gaining popularity among some of the Arab leaders within the city since April 2012, proposing protection from Kurdish forces’ expansion into the province.23

In the autumn of 2012, the central government formed a new Dijla Operations Command, based in Kirkuk and in charge of overseeing security operations for Kirkuk and the neighboring provinces of Salaheddine and Diyala. The establishment of the Dijla Operations Command involved placing Kirkuk police under the Operations Command’s authority. Kurdish leaders responded negatively to this move, calling for the command’s dissolution.

This has resulted in an increasing militarization of Kirkuk. As of the end of 2012, the Iraqi army has deployed increasing armaments on the southern outskirts of Kirkuk, while the peshmerga increased in number and are advancing closer to the city center. Despite clashes that have already erupted in the city of Tuz Khormato, it is unlikely that the two sides will engage in a full-scale confrontation. Instead, the deployment of an army division to confront the Kurdish security forces has given the prime minister more chances to acquire the support of some of the Arab leaders within Kirkuk and the neighboring provinces.

As demonstrations began in the Sunni provinces, some leaders from Kirkuk’s Arab district (Hawijia) supported the mobilization. Generally, Kirkuk’s Arab leaders found themselves in an uneasy position, caught between expressing solidarity with the Sunni communities’ mobilization against the central government and the necessity to maintain their alliance with the prime minister to protect them in their contest with the Kurds.

Attempts at Opposition

As he came to power in December 2010, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki had an uneasy run. But so far, none of the attempts to remove the prime minister from his post has succeeded. Indeed, because of his own political and security power base and the divisions among his opponents, the prime minister has placed himself in a very powerful political position. As the Maliki government faced the threat of a no-confidence vote, an Iraqi parliamentarian commented: “At the moment, the only person who matters—the only person who can withdraw confidence from Maliki—is Maliki himself.”24

The first seven months of 2012 witnessed several efforts to topple Maliki’s government. In January, Iraqiyya cabinet and parliament members launched a boycott of the government. In April, Maliki’s opponents Osama Nujeifi, Moqtada al-Sadr, Ammar al-Hakim (the leader of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq), and Jalal Talabani, in a meeting organized by the president of the Kurdistan region Massoud Barzani, met in Erbil, and the process escalated in May when these leaders sought to collect votes and signatures in parliament to withdraw confidence in the prime minister. Then in July, Allawi, the Sadrists, and KRG President Barzani resorted to a lesser tactic by seeking to question Maliki in front of the parliament for legal and constitutional violations, but failed once again in their attempt.

The opposition has shown itself to be increasingly divided and unable to form a united front against Maliki.

In fact, the Sadrists, who remain the most fervent of Maliki’s Shia rivals, have repeatedly threatened to withdraw support for the government, called for the National Alliance to substitute Maliki with another coalition member, and taken part in most of the initiatives organized by Maliki’s rivals. But none of these efforts triggered major defections or reactions within the Shia National Alliance, which provide the prime minister with a broad political majority. Within that community, Maliki can count on a broad political majority.

The opposition has shown itself to be increasingly divided and unable to form a united front against Maliki. Iraqiyya has been reduced to a loose aggregation of leaders rather than a cohesive political bloc. Its boycott of parliament lasted only one month; 76 Iraqiyya members participated in the parliamentary session on January 29, and Iraqiyya’s ministers returned to their posts a few days later. In April, the list confirmed its disunity when it was unable to rally its 85 remaining members of parliament to withdraw confidence in the government. In June, Iraqiyya’s leader and the deputy prime minister, Saleh al-Mutlaq, who had initially accused Maliki of being a dictator, proposed dialogue and negotiations with the prime minister, declaring that withdrawing confidence in the government is “not an option.”25

December 2012 demonstrations in the Sunni provinces once again raised calls for the prime minister to step down. Beyond the popular discontent, leaders seem to have found agreement in their opposition to the prime minister, and on January 26, Iraq’s parliament passed a law that would limit the prime minister to two terms in a bid to hamper Maliki’s aspirations to serve a third term. But so far they have been unable to join forces to dismiss him from power or join together into a political alliance. Iraqiyya is even more divided than before and deeply disconnected from the mobilization taking place in the provinces. It could hardly find the basis for an agreement with the Sadrist Trend, for instance, which supported demonstrations and the anti–prime minister campaign. The Kurds remain the players that could shift the balance.

Barzani, who is among Maliki’s most outspoken opponents, has continually threatened to use a no-confidence vote to show how vulnerable Maliki is and to strengthen his own negotiating position in the process, but he has never gone through with the threat. During the summer of 2012, Barzani repeatedly attacked Maliki and stepped up calls for the prime minister’s resignation, but Patriotic Union of Kurdistan leader and Iraqi President Jalal Talabani did not support the no-confidence motion. That, in turn, did away with the possibility of a vote completely. This episode not only reflected the long-standing rivalry between the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan but also indicated that the Kurds perhaps only aim to weaken Maliki but not topple him. Furthermore, since the demonstrations began in December 2012, President Barzani, in contrast to others, has not called for the prime minister to step down. He might prefer to deal with one main leader on the Arab side of Iraq rather than a chaotic array of power centers.

The Benefits of Brinkmanship

As it currently stands, the Kurds remain the most significant and unified counterbalance to the prime minister’s power. Throughout 2012, tensions have escalated between the two sides. Erbil and Baghdad clashed over which side had sovereignty over the disputed territories and over the division of Iraq’s oil and gas resources, as well as the redistribution of the budget. The struggle with the Kurds also extends to the inner ranks of the Iraqi army, where some high-ranking military officers are Kurdish. Barzani has repeatedly denounced Maliki’s grip on the army and the marginalization of Kurdish officers from decisionmaking positions within it.26

All indicators point to more tension. Baghdad and the Erbil have in effect entered into an arms race. In 2012, the Iraqi government allocated 17.1 trillion Iraqi dinars to the security and defense budget, approximately 14.5 billion dollars, and is now planning to create a category of financing exclusively intended for the purchase of heavy weaponry. The KRG has responded by strengthening its own security apparatus. In July, the Kurdish authorities announced the creation of a Kurdish Security Council in charge of organizing security in the region and under the direct supervision of the Kurdish cabinet.27

This has already resulted in the increasing deployment of forces over the disputed territories and in Kirkuk in particular. The coming months could see tensions rise to a crescendo over the territories disputed between the two sides, though they most likely will not explode. Baghdad’s conflict with the Kurds could veer in a different direction. Maliki and Barzani could both benefit politically from showing their constituents that they can stand up to each other.

In view of the upcoming provincial elections in April 2013, both sides may find it convenient to share authority over Iraq rather than rush into open confrontation. The prime minister would benefit from maintaining the status quo—which currently places him in a position of political primacy—while capitalizing on the tension over the disputed territories to pressure Sunni Arab leaders to maintain their strategic alliance with him as a way to counter the Kurds.

Similarly, Barzani would benefit from ensuring that the prime minister is his lone counterpart. The Kurds might prefer dealing with Maliki in the disputed territories to facing a largely Sunni party, like Iraqiyya, or they might prefer the simplicity of dealing with one power broker on the Arab side rather than two or more, which would be the case if Maliki lost his dominance. The ruling Kurdish leadership has already benefited from the escalating tensions with Baghdad to reinforce nationalist feelings among the Kurds and the leaders’ image as protectors of the Kurdish national cause. In the words of a Kurdish parliamentarian, Mahmoud Othman, “Both Maliki and Barzani like to be at the edge of war; Barzani helps Maliki and Maliki helps Barzani to gain the people’s consensus in the street.”28

The disputes between the Kurds and the Baghdad government might lead to a new status quo rather than escalate into open conflict. Despite the increasing militarization and tensions between Maliki and the KRG over oil and gas, the budget, and the disputed territories, these tensions may give way to negotiated concessions in each domain, resulting in a balance of power between the prime minister and the Kurds. Even the arms race between them could lay the foundations for coexistence on the basis of mutual deterrence rather than fueling conflict. Neither side has an interest in real armed conflict, and each has a political interest in using the disputes to consolidate its own political position.

Beyond Power Consolidation

Maliki’s rise to a dominant position seems secure in the short term, but an excessive consolidation of power also comes with risks to that authority. The prime minister’s power is only sustainable if all of Iraq’s main political groups have a genuine stake in governing.

Maliki proceeded in this direction only slightly by including members of different political affiliations and sects in his entourage and assigning them roles and some authority within his system. In September 2012, the prime minister started to prepare for the 2014 legislative elections, opening negotiations with the Sunni leaders Saleh al-Mutlaq, Rafi al-Issawi, and Osama Nujeifi as well as with Kurdish parties such as the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan and Gorran. By doing so, he was aiming to become the center of a cross-sectarian and multiethnic political alliance that would potentially include some Sunni and Kurdish components but would not include the prime minister’s longtime Shia rivals, the Sadrists. However, the December standoff with the Kurds and tensions with Sunni political forces have seriously jeopardized the prime minister’s negotiations and put Maliki further at odds with both sides.

Power consolidation through a policy of exclusion has created a climate of continuous crisis that deeply affects the country’s stability. The popular uprising in the Sunni provinces and growing tensions with the Kurds are proof of that. Building an inclusive government and bringing an end to the climate of political crisis is the responsibility of both the prime minister and those who oppose him. Instead of remaining divided and focusing their energies on their struggle against the prime minister, opposition groups should unite and rebuild ties with their constituents in the provinces.

All Iraq’s political groups should focus their efforts on building effective political leadership. That leadership should work to strengthen the country’s currently weak legal framework, bolster state institutions, and rebuild ties with segments of Iraqi society that feel disenfranchised by the government, and poorly represented by the opposition.

Looking beyond Iraq’s borders, a government inclusive of different sects and ethnic groups would strengthen the country’s aspirations to reenter the regional and international scene. To succeed in regional foreign policy, the government has to pursue a domestic formula that leverages Iraq’s ethnic and sectarian diversity to strengthen the country’s relationships with all its neighbors. Such a transition has already begun. In 2012, Iraq’s foreign policy began to depart from the country’s recent history of regional and international isolation. In March 2012, Iraq hosted an Arab League summit and began normalizing its relationship with its long-standing adversary Kuwait, engaging in negotiations over the disputed borders between the two countries, regulating navigation over their shared waterways, and agreeing on the development of disputed oil fields.

Maliki has moved to strengthen his political power. And in this rise to dominance, his influence over the armed forces has been crucial. Whether the prime minister will wield that power effectively, favoring the building of state institutions and the reemergence of Iraq’s role in the region, or whether his attempt at dominance will only usher the country into a long period of internal crisis is yet to be seen.

Appendix

No Iraqi army forces are deployed in the provinces that are part of the Iraqi Kurdistan region (Erbil, Sulaymanya, and Dohuk), which are fully under the control of the Kurdish peshmerga forces. Both Iraqi army and peshmerga forces are deployed in the territories disputed by the Kurdistan Regional Government and the central government in Baghdad; those territories are part of Kirkuk, Ninewa, Salaheddine, and Diyala Provinces.

Throughout 2011 and 2012, most army divisions remained deployed in the north of the country. Anbar, Ninewa, Salaheddine, and Diyala have army divisions and Operations Commands on their soil (Anbar: the Seventh Army Division and Anbar Operations Command; Ninewa: the Second Army Division and Ninewa Operations Command; Salaheddine: the Fourth Army Division and Samarra Operations Command; Diyala: the Fifth Army Division and Diyala Operations Command). Dijla Operations Command, established in September 2012, should supervise all security forces in Salaheddine, Diyala, and Kirkuk Provinces.

Notes

1 Among the most important unissued laws the report mentions are a law regulating the functioning and administration of political parties and the reform of the bylaw itself, which would ease parliamentary legislating activities. See International Crisis Group, Failing Oversight: Iraq’s Unchecked Government, Middle East report no. 113, September 26, 2011, 21.

2 See International Crisis Group, Iraq’s Secular Opposition: The Rise and the Decline of Al-Iraqiya, Middle East Report no. 127, July 31, 2012.

3 See Faleh A. Jabbar, “Maliki and the Rest, a Crisis Within a Crisis,” Iraqi Institute for Strategic Studies, June 2012; T. Dodge, “The Resistible Rise of Nouri al Maliki,” Open Democracy, March 2012.

4 Mark Heller, “Politics and the Military in Iraq and in Jordan 1920–1958: The British Influence,” Armed Forces and Society, vol. 4, no. 1, (1997): 75–99.

5 Andrew Parasiliti, “Friends in Need, Foes to Heed: The Iraqi Military in Politics,” Middle East Policy, vol. 7, no. 4, (2000): 130–45

6 Elizabeth Picard, “Arab Military in Politics: From Revolutionary Plot to Authoritarian State,” in The Arab State, edited by Giacomo Luciani (London: Routledge, 1990).

7 Author’s phone conversation with Major General P. Eaton, August 26, 2011.

8 At first the idea was to build a defensive army which would not constitute a threat to the neighboring countries. But the intent of June 2003 changed very much once the insurgency started. Throughout 2005, the army expanded and deployed as an internal security force; we went from an army that could defend Iraq from other countries to an army which operates within its borders to defeat the insurgency.” Author interview with Major General Jeffrey S. Buchanan, U.S. army spokesman, Baghdad, September 26, 2011.

9 In 2003 and 2004, the Coalition Military Assistance Training Team (CMATT)—recruited officers according to precise criteria: filling an ethnic and sectarian quota of 30 percent Sunni, 30 percent Kurd, and 40 percent Shia, and disqualify those who had a rank higher than colonel in the former army. Even those who were accepted had often to enter with two ranks lower than they held in the former army. See Patricia Brasier, But Ma’am the Security: The Manning of the New Iraqi Army (Infinity Publishing, 2008).

10 Author interview with J. K., a member of the C1 (Recruitment and Manning of the IA) Coalition Military Assistance Training Team in 2003, Baghdad.

11 Operations Commands are ad hoc structures set up to direct the operations of the army divisions assigned within a given territory. One Operations Command can be tasked with directing different units deployed in different provinces. Moreover, Operations Commands are headed by the highest levels of the upper officer ranks—general or lieutenant general—while the army divisions can be headed by lower ranks. For instance, the newly established Dijla Operations Command, headed by Lieutenant General Abdulamir al-Zaidi, directs the army division in Kirkuk, Salaheddine, and Diyala Provinces. See Appendix.

12 Art. 57 (Fifth clause; C) of the Iraqi Constitution stipulates that “the Council of Representatives should approve the appointment of the Iraqi Army Chief of Staff, his assistants and those of the ranks of division commanders and the director of the intelligence service and above based on a proposal of the cabinet.” According to an Iraqi lawmaker “since 2010 the government appointed operation commanders, head of divisions without the approval of the Parliament. […]” Author interview, Baghdad, January 24, 2013.

13 See International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), “Middle East and North Africa,” The Military Balance 2012, vol. 112, no. 1 (2012): 303–360. See International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), “Chapter Seven: Middle East and North Africa,” The Military Balance, 303–60: “as of June 2011, the Iraqi security forces employed 806,600 people, spread between the MoD, the Ministry of Interior (MoI) and the Prime Minister’s Counter-Terrorism Force.… [the Iraqi MOD] employs a total of 271,400 personnel, spread between the Iraqi army (193,421), the air force (5,053) and subsidiary organizations. The Ministry of Interior employs 531,000. The Iraqi police has 302,000 on its payroll, the Facilities Protection Service 95,000, Border Enforcement 60,000, Iraqi Federal Police 44,000 and Oil Police 30,000. In 2010, the total number of people employed by the security forces equaled 8% of the Iraqi workforce, or 12% of the total population of adult males.” See International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), “Middle East and North Africa.”

14 See Law of Governorates Not Incorporate into a Region as amended by Law 10 of 2010. Art. 31 (Tenth clause) “The governor shall have direct authority over the local security agencies and all authorities tasked with the protection duties relating to peace and order within the governorate, except for the armed forces units.” Art. 7 (Tenth clause): “The governors approve the local security plans submitted by the security agencies in the governorate through the governor in coordination with the federal security agencies with due consideration of their security plans.” Also, according to Art. 7 (Ninth Clause) C, “The governor shall approve the nomination of three out at least five candidates proposed by the governor for the senior positions in the governorate [which include the police chief] by the absolute majority of the council members and the competent ministry shall appoint one of them.” Removal of senior officials [police chief included] follows the same procedure and is regulated by the same article. The text of the law is available at www.iraq-lg-law.org/en/webfm_send/765.

15 See Appendix.

16 See “A Local Official: We Will not Allow the Army to Control Anbar,” AK News, May 2011. During summer 2011 following the imposition of the army’s curfew over the province, Anbar officials demanded the replacement of the operations commander with an officer from the provinces and the withdrawal of the army from the provinces. See the Anbar Provincial Council website, http://council-alanbar.com.

17 During 2011 the Korean company KOGAS, together with the Kazakh company GasMunalGas, had plans to develop the Akkas gas field but the project has been repeatedly delayed due to disagreements between the local and central government. See “Akkas Gas Deal Delayed Again,” Iraq Business News, February 26, 2011, www.iraq-businessnews.com/2011/02/26/akkas-gas-deal-delayed-again.

18 Throughout 2011 and 2012, Anbar, Salaheddine, Diyala, and Ninewa saw the replacements of their senior political and security officials (governor, head of provincial council, police chief). See Aswat al Iraq website archives (2011–2012), http://en.aswataliraq.info.

19 According to the All Iraq News Agency website www.alliraqnews.com, in July the Ministry of Defense announced the opening of recruitment centers to reintegrate officers in Anbar, Salaheddine, and Diyala. In particular, the Anbar Operations Command has activated recruitment centers in Qaim and Falluja.

20 In December 2010, the Maysan Provincial Council dismissed State of Law governor Mohammed Shayaa al Sudani (State of Law), replacing him with Ali Dway (Sadrist Trend). His fellow party member Hussein Reza Saidi Is the Council Chairman. See Maysan Provincial Council website, http://missan-council.net.

21 Maysan provincial council website reports of several meetings between Maysan provincial officials and the Commander of the Iraqi Ground Forces and with the head of the 10th Division of the Iraqi Army over the management of security in the province.

22 According to Awsat al-Iraq, Basra saw several replacements of local political and security officials. However, throughout the year, after each replacement, the police were left in control of the security file in joint cooperation with the army.

23 See Kirkuk Now website archives (2011–2012), www.kirkuknow.com.

24 Mustafa Habib, “Getting Rid of Nouri: PM’s Critics Consider Options to Remove ‘Dictator,’” Niqash, May 3, 2012, www.niqash.org/articles/?id=3042.

25 Ibid.

26 See Hevidar Ahmed, “MP Warns of Imminent Iraqi Attack on Kurdistan,” Rudaw, July 10, 2012, www.rudaw.net/english/kurds/4939.html.

27 See “National Security Council Will Combat Security Challenges in the Region and in Iraq,” AK News, July 12, 2012, www.aknews.com/en/aknews/3/316667.

28 Author Interview with Kurdish lawmaker Mahmoud Othman, Baghdad, December 4, 2012.