On September 5, the Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Agency (EDA) signed a memorandum of understanding with the Department of Defense’s Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), in part to help integrate the EDA’s Tech Hubs with DIU’s domestic and international initiatives. The Tech Hubs program was established by the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 to spur regional innovation across the United States in service of economic development and national security objectives. Although the Tech Hubs program ostensibly is domestic in nature, it, like other aspects of recent landmark legislation, has features that could have important implications for international economic relations, particularly with the African continent.

October 23, 2023, saw the official designation of the first thirty-one Tech Hubs, comprising more than 1,400 total organizations, of which 500 were from private industry.1 These hubs focus on a broad range of strategic sectors, including quantum technology, critical minerals, the energy transition, and semiconductor manufacturing. The primary benefit of designation was eligibility to apply for implementation funding from the EDA, the results of which were announced on July 2, 2024. Of the thirty-one Tech Hubs, twelve were chosen to receive funding, with awards ranging from $19 million to $51 million per hub, for a total of $504 million. These awards are intended to help the hubs “scale up the production of critical technologies, create jobs in innovative industries, strengthen U.S. economic competitiveness and national security, and accelerate the growth of industries of the future in regions across the United States.”

Beyond their potential to accelerate growth and foster job creation domestically, these hubs have the potential to feature prominently in the United States’ international economic relations with the African continent and the rest of the world. The agglomeration of cutting-edge industry players, leading academics, and local stakeholders––brought together into discrete units and backed financially by a federal program—present concrete opportunities for subnational diplomatic and international economic engagement, given their concentration in clearly demarcated cities and municipalities.

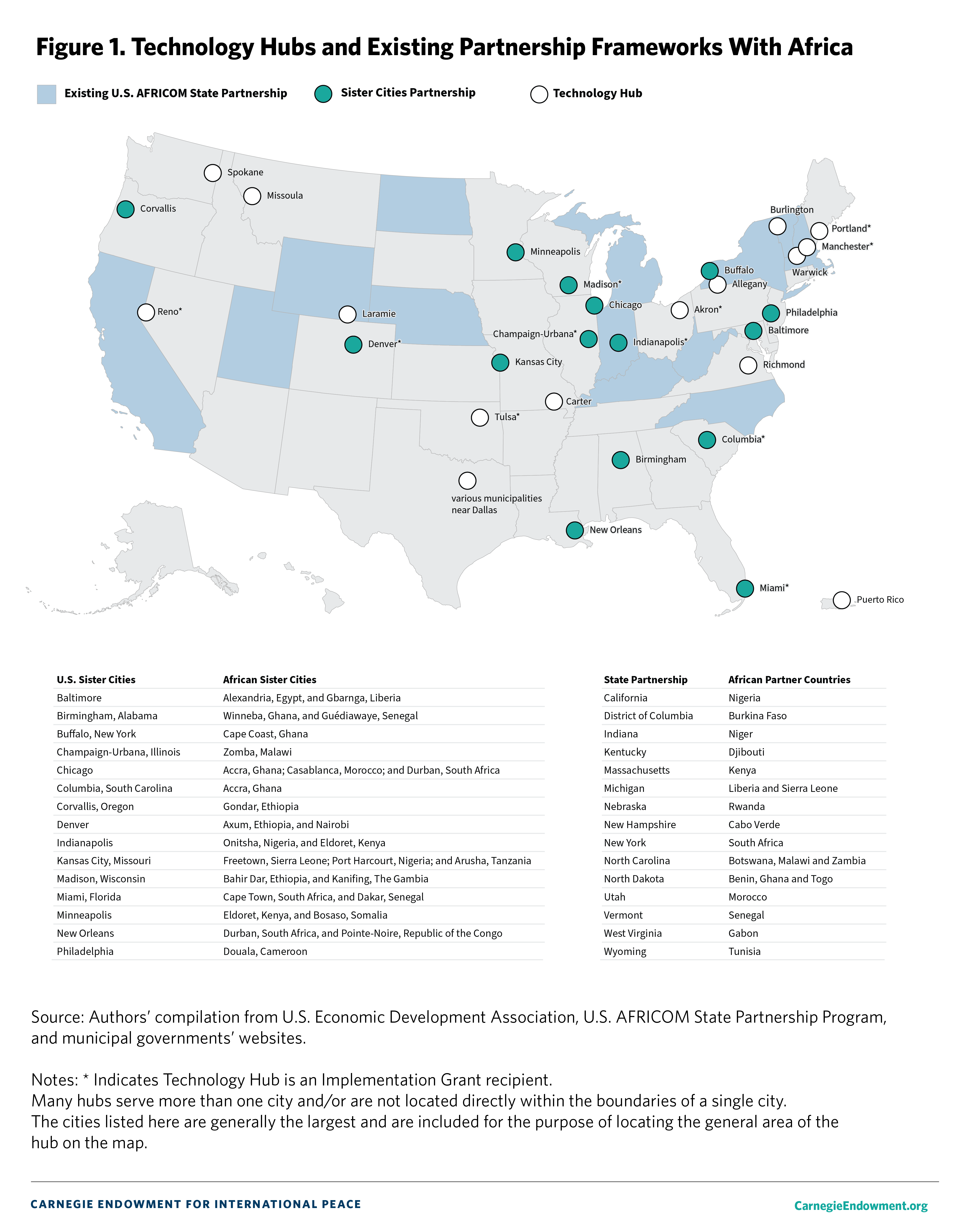

Two potential channels by which cities and municipalities served by a Tech Hub could engage specifically with African countries are the sister city and U.S. Africa Command State Partnership Programs. More than a half-dozen of the thirty-one Tech Hubs are located in states with an existing State Partnership Program, and dozens more cities adjacent to these hubs have sister city agreements with at least one African city (Figure 1). The State Partnership Program is focused on security cooperation and could be a vehicle through which, for example, innovations in grid resilience technology could be disseminated to strategic partners on the continent. Furthermore, even though the sister city program often is understood as being centered around facilitating cultural ties, interested cities can leverage the framework to scale up economic and technological cooperation with relevant African partners. African firms may even be able to participate in current or future consortia, as the EDA guidelines explicitly allow such involvement.

Three examples illustrate what the nature of what this collaboration could entail. First, consider the South Florida ClimateReady Tech Hub, one of the twelve implementation awardees. The goal of this hub is to scale up and accelerate the commercial viability of advanced concrete and cement, which both uses less carbon in its production and is more resilient to extreme weather events. At the most basic level, given their need for additional infrastructure and disproportionate vulnerability to extreme weather, many African countries are an obvious source of demand for such a product. Furthermore, Miami (located within the hub’s service area) has had a sister city partnership agreement with Cape Town, South Africa, since 2013, through which it recently conducted a county-level mission aimed at expanding bilateral trade and economic cooperation. As the hub develops, it could become a material component of future trade missions, deals, or investments between the municipalities.

A second example comes from SC Nexus for Advanced Resilient Energy, an awardee centered around Columbia, South Carolina, which has a sister city partnership with Accra, Ghana. The objectives of SC Nexus revolve around improving clean energy grid resiliency, particularly in the context of cyberthreats. Developing more secure and reliable critical energy infrastructure, including grid systems, is a priority for the United States and its allies. By quickly incorporating innovations in this domain into international security and foreign policy apparatuses, participants in both continents can directly support national security interests and indirectly support commercial feasibility through the guaranteed demand for these innovations. Such an initiative would serve both core directives of the hubs program.

A final set of examples is the Nevada Lithium Batteries and Other EV Material Loop and Lithium Valley Clean Tech Strategy Development Consortium. The Nevada Loop is another of the twelve awardees, whereas the Lithium Valley Consortium has to date only received a $500,000 Strategy Development Grant.2 Both the Nevada Loop and Lithium Valley Consortium are led by universities and seek to generate innovations around lithium supply chain optimization from extraction and processing through to end-of-life recycling. Especially given their academic research orientation, there may be scope for collaborations and shared learning with African universities in countries endowed with lithium deposits, such as Ghana and Zimbabwe. Although the direct objective of these programs is to develop a domestic lithium supply, the massive increase in projected demand for the mineral by 2050 means that the United States has a direct interest in cultivating sustainable supply chains from reliable international partners. Technical collaboration centered around these burgeoning innovation centers could be an excellent way to both develop and bolster the supply chains in African partner countries as well as help ensure access.

The types of collaborations envisioned in the three examples above go beyond the immediate purview of the specific consortium members; consequently, these potential linkages will require concerted policy support and advocacy from key stakeholders to be successful. Fortunately, the hubs program’s framework already includes space for these policy supports. As part of the implementation funding applications, the thirty-one Hubs secured around 1,000 policy commitments from regional actors, demonstrating the public support for their efforts. Additionally, the updated Benefits of Designation document shows that Tech Hubs not only will receive grant support and assistance with raising capital (as through the recent Innovative Capital Summit), but also will have access to several federal organizations that may help in operationalizing international cooperation, such as the Export-Import Bank of the United States, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Energy. As the hubs continue to develop, leveraging these interagency access benefits will be key to realizing their international potential.

In the immediate term, the most important step will be to continue to fund the Tech Hubs program. The CHIPS and Science Act authorized $10 billion for the program, of which $541 million has thus far been appropriated to the EDA. Congress should ensure that the remainder of the authorized funding is provided in a timely and consistent manner so the EDA can continue to support the development and expansion of the hubs program. If adequately financed—and fully leveraged by relevant federal and subnational actors—these emerging strategic industrial clusters may offer potential tools for actionable foreign and international economic policy. Particularly with respect to Africa, using specific hubs as fulcrums around which to expand city-level economic partnerships, support national grid infrastructure in furtherance of the energy transition, or foster research collaborations for supply chain innovations, is a direct way to help realize the promise of shifting the U.S. relationship with the African continent “from aid to trade.”

1Examples of other entities included in consortia are local and tribal governments, academic institutions, and labor organizations.

2Strategy Development Grants are distinct from Tech Hub designation and are intended to help enable consortia to continue to develop their regional economic development strategy, particularly in the hopes of receiving a full Tech Hub designation in the future.