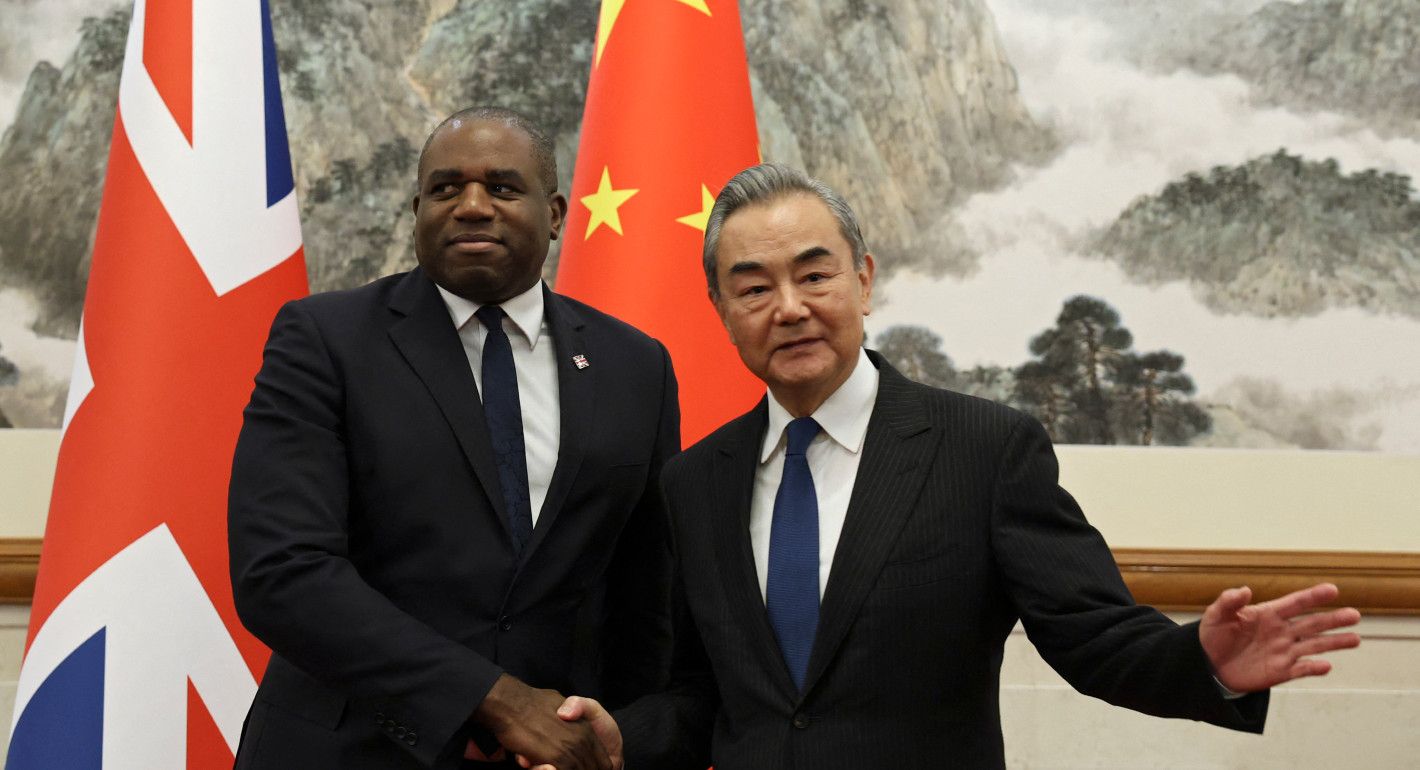

On Friday, British Foreign Secretary David Lammy will commence a two-day visit to Beijing and Shanghai. His visit comes amid an audit of the UK-China relationship and a promise by Lammy to overhaul Westminster’s relationship with China.

Any deep rethink is unlikely to touch sensitive issues like human rights, Chinese investment in UK critical infrastructure, or Chinese influence operations in the UK. But there is an increasingly pressing issue where Sino-British national security interests have aligned: risks associated with advanced and empowered AI systems that can be misused by nonstate actors, or simply go rogue, to cause mass casualties or disrupt critical infrastructure. It is here where carefully scoped UK-China engagement is both needed and politically feasible.

China, the UK, and the United States all see AI as a cornerstone of national power going forward, and they are fiercely competing to lead in the field. Deep geopolitical rivalries make any form of Sino-Western cooperation politically challenging and often technically inadvisable. Even in this low-trust environment in which broader ideologies and priorities directly clash, there are windows for coordination where interests clearly align.

One such area is managing the risks at the frontier of AI. For example, OpenAI’s o1 model, released last month, displayed “medium-level risks” for chemical, biological, radioactive, and nuclear (CBRN) weapon development—meaning, for example, that it could “help experts with the operational planning of reproducing a known biological threat.” The model also “sometimes instrumentally faked alignment during testing.” This means the model feigned compatibility with human values and goals but deceived its creator to pursue its own goals against the developer’s interests.

Whether a frontier model is developed and deployed by the United States, China, the UK, or any other country, no one wants a terrorist to be able to easily develop a bioweapon. Likewise, no one wants a powerful AI system to lie to its developers, especially one integrated into military systems or critical infrastructure. For now, AI systems may seem incapable or well-managed enough that these risks appear distant or unlikely. But given the rapid development of frontier models in both the West and China, leading thinkers and policymakers on each side are increasingly raising the alarm about these global risks.

For its part, the UK has been a trailblazing AI safety advocate and global AI governance leader, noting that AI has the potential to erode public safety or threaten international security. Last year, the UK created the world’s first AI Safety Institute (AISI), successfully ran the first AI Safety Summit, and funded the first International Scientific Report on the Safety of Advanced AI. All these initiatives have since gathered global traction. The UK’s AISI has become the blueprint for a growing network of AISIs in other countries. South Korea and France have organized their own AI summits based on the UK model, and the UN plans to establish an international scientific panel on AI that builds on the UK-funded original.

Most notably, the UK made the politically challenging but ultimately correct decision to invite China to its AI Safety Summit at Bletchley Park. While acknowledging that some of China’s interests in AI diverged substantially from those of its democratic counterparts, the UK recognized the broader need to bring China to the table to address potential catastrophic harms. The UK was well-positioned to leverage its international convening power to serve as a bridge between Washington and Beijing. The results were powerful: the United States, China, the UK, the EU, and twenty-five other countries signed the Bletchley Declaration, calling for a global approach to tackle opportunities and risks connected to AI.

Since Bletchley, policymakers and analysts have seen growing concern around catastrophic risks inside China’s AI community. In China, as in Britain, these risks are now on the agenda and seen as a national security imperative.

China’s leaders now repeatedly praise Bletchley’s positive role in international AI governance. But it’s not just Bletchley. The highest echelons of China’s leadership are increasingly wary of catastrophic AI risks. Senior Chinese officials, including Premier Li Qiang and Foreign Minister Wang Yi, have explicitly called for the implementation of safety measures to prevent loss of human control, where AI systems act in unintended ways that their developers cannot reverse.

Most critically, China’s Third Plenum decision, which laid out the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) long-term economic and social vision, underscored the need to create a regulatory body focused on AI safety. Importantly, the document explicitly and directly linked AI safety mechanisms, public security, and national security. The 100 Questions Study Guide, a document clarifying Third Plenum action items edited by Chinese President Xi Jinping and three other top advisers, reinforced the linkage between AI safety and national security and noted the importance of taking AI safety seriously. In short, there’s a growing body of evidence that the CCP leadership is aware of potentially catastrophic AI risks and is considering how to tackle them.

These internal developments inside both the UK and China have resulted in a surprising convergence in Sino-Western understanding of frontier AI safety risks. Leading scientists, including Turing Award winners in the West and China, have signed consensus statements outlining steps the international community can take to address these risks. These proposals are unique in that they are both actionable and unlikely to increase China’s offensive or dual-use capabilities or unintentionally reveal information about capabilities possessed by the UK or other Western actors. Put simply, they offer the possibility for coordination in a low-trust, highly securitized environment.

The scientists’ statement outlined three prudent ways for the UK, China, and other governments to work together. First, both countries should consider building emergency preparedness agreements and institutions. This involves establishing methods for convening AI safety authorities across countries and establishing a minimum set of safety preparedness measures. Second, they should consider building a safety assurance framework. This would be used to ensure that the development and deployment of models demonstrating certain levels of risk are no longer developed. Lastly, both countries should fund independent global AI safety and verification research. It is critical that all countries developing frontier technologies have ways to verify the safety evaluations conducted by model developers. This research would fund the secure and nonproliferating development of verification methods, such as by third-party auditors.

This is not to say that the UK can and should engage with China on the full range of AI issues. For example, China’s generative AI law requires that AI-generated content reflect its core socialist values in ways that undermine core British commitments to freedom of expression. Moreover, even within AI safety, some forms of coordination are clearly riskier than others. The UK should carefully examine any technical exchanges involving AI safety to ensure they do not inadvertently end up enhancing China’s AI capabilities. The UK already has sufficient internal capabilities to carry out these technical risk assessments. It should not let fear of nuance or complexity get in the way of essential policy action.

Longtime UK-China commentator Sam Hogg has argued that the UK’s relationship with China has gone through three eras in the past decade. First, the Golden Era, now undeniably dead, which was defined by openness and cooperation. It was succeeded by an Alarm Era, centered around growing concerns about Chinese security risks. We are now in the Shaping Era, where the easy policy decisions have already been made and only the hard, long-term, gray-area questions loom. The UK and China now have an opportunity to help shape the global discussion around addressing global frontier AI risks. Time will tell if they can capitalize.