This publication is a product of Carnegie China. For more work by Carnegie China, click here.

Now that China’s necessary data for the second quarter of 2024 has been released, it makes sense to provide a quick summary of the country’s recent debt performance. According to China’s National Institute for Finance and Development (NIFD), “China’s macro leverage ratio is now higher than other major economies, which is due to years of persistently weak price increase.” It continues: “We need to crank up countercyclical adjustment to bring about inflation to counter the rising leverage.”

This is a strange argument to make, although it is not uncommon. On the surface, it is easy to see why the NIFD might think that deflation has driven up the country’s debt burden. A country’s debt-to-GDP ratio rises as a function of the nominal growth in debt versus the nominal growth in gross domestic product (GDP), and in a deflationary environment, the nominal growth of GDP is lower than the real growth. That makes it seem that the debt burden is accelerating even as nominal growth in debt is decelerating. (In the second quarter, outstanding debt rose at the slowest pace since 2001.)

But it makes no sense to recognize that deflation reduces nominal GDP growth without recognizing that it also reduces nominal debt growth. The problem is not deflation but non-productive investment. As long as China uses debt to fund non-productive investment, the debt-to-GDP ratio will rise just as quickly with deflation as it did with inflation.

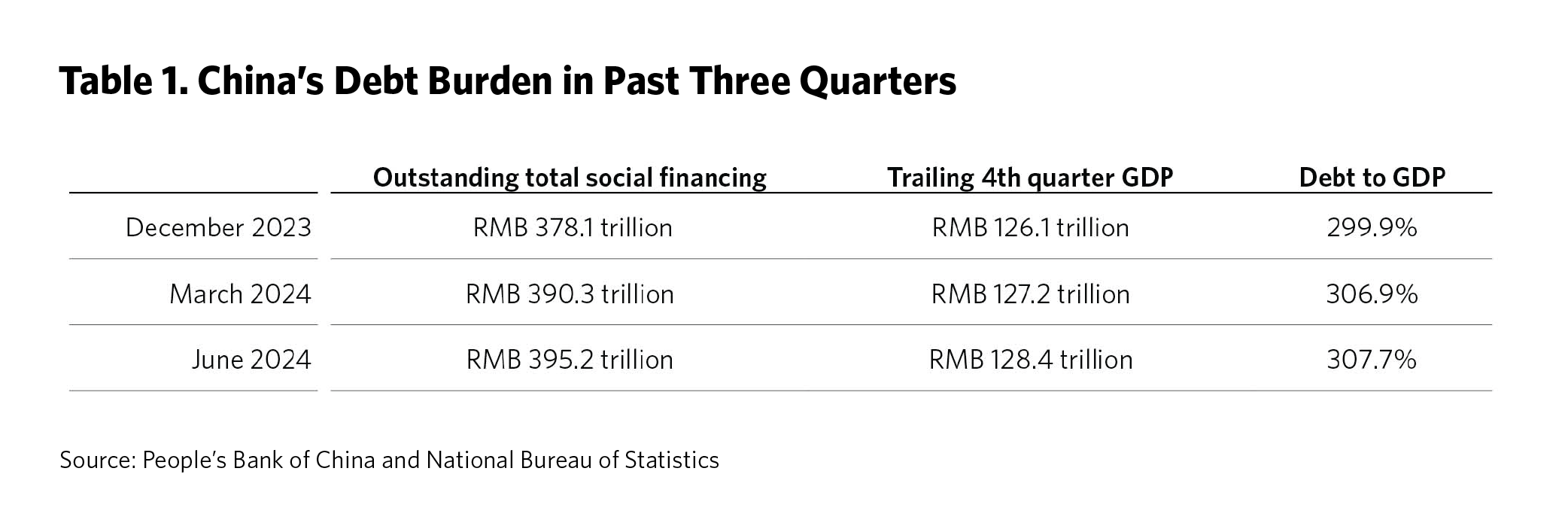

And what has the Chinese debt burden done this year? Table 1 shows the numbers for each of the past three quarters.

The NIFD has a slightly different definition of debt, so it measures China’s “macro leverage” 12.1 percentage points below mine, but the two measures move almost in lockstep (see the NIFD’s measure from a graph published on July 25 in Caixin).

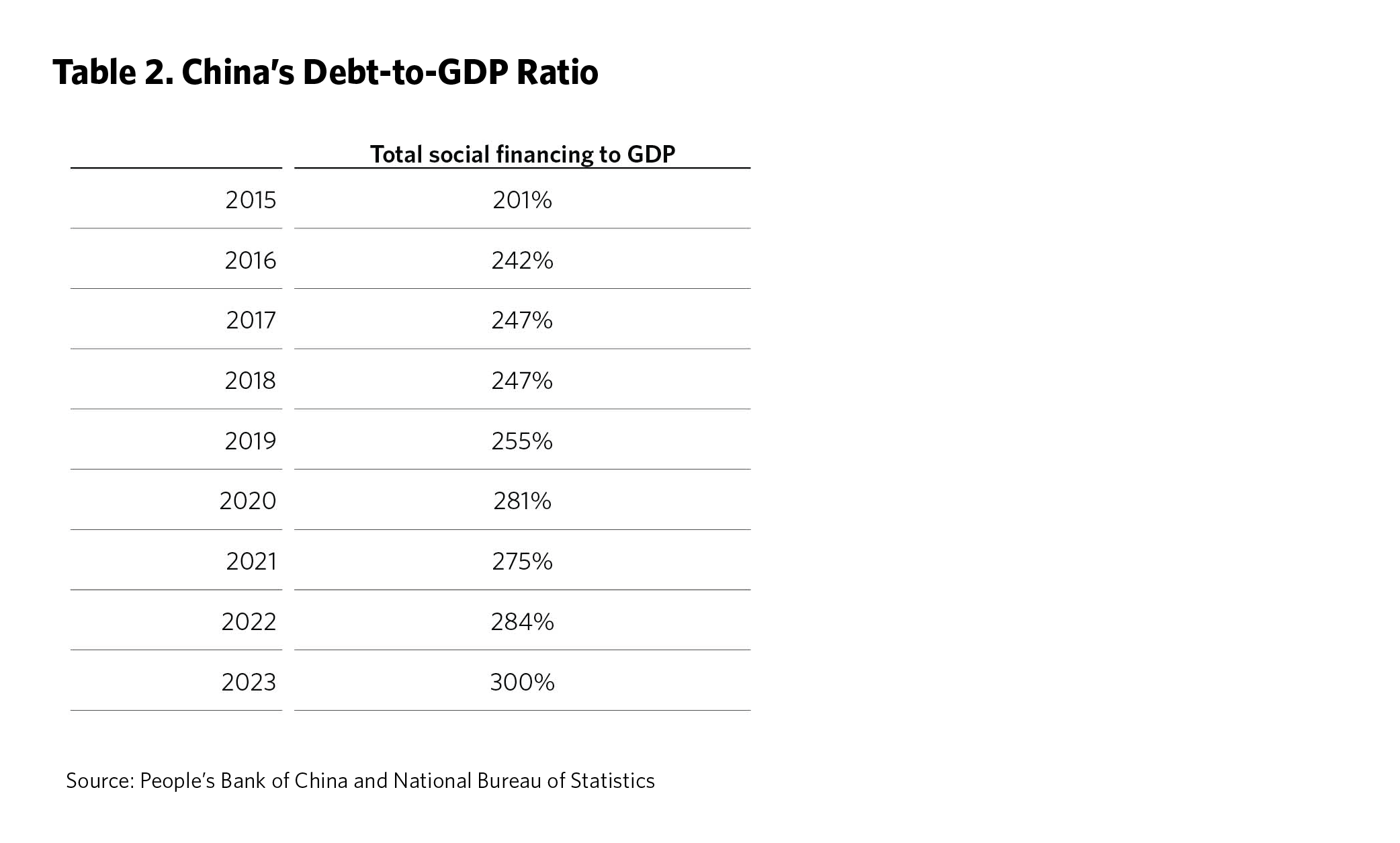

Both measures show that the growth in nominal debt and in the country’s debt burden slowed in the second quarter. Total outstanding debt rose by 9.8 percent at the end of 2023 from a year earlier and by 8.7 percent and by 8.1 percent at the end of the first and second quarters, respectively. But given the slowdown in nominal GDP growth, this is still a very large increase. As shown in table 2, China’s debt to GDP has risen on average by about 12 percentage points per year. Therefore, an 8-percentage-point increase in the first six months does not suggest any slowdown in the debt burden.

The good news might be that credit growth slowed sharply in the second quarter, and perhaps whatever drove the deceleration in debt might continue into the rest of the year. But it is still unclear if that really happened. There was an actual (and unexpected) decrease in the outstanding amount of total social financing in April 2024. This was the first time such a decrease has ever happened. Although we don’t have the full data, it seems that the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) made a major adjustment to the way in which banks and major borrowers had been creating additional loans and deposits.

These additional loans and deposits did not represent real borrowing, but they were encouraged by the banks nonetheless to boost activity and reported business loans, and so they had been distorting the data (Caixin explains the process here). It is quite likely that the deceleration in credit growth in the second quarter was driven mainly by an accounting adjustment in April. The extent of the adjustment remains unclear, but for outstanding total social finance to decline in April, it must have been substantial.

If that is the case, the real growth in outstanding debt was slightly lower than reported in the period before April and more than reported during April. What this suggests is any reported deceleration in credit growth in the second quarter may have been overstated. It still implies a substantial slowdown in the growth of the debt burden but perhaps only by 1.5–2.0 percentage points, instead of the 8 percentage-point shown in the NIFD numbers.

The conclusion isn’t especially surprising. By now, almost everyone in economic policymaking circles—not just the NIFD—is concerned about China’s high and rising debt burden, but there is little evidence that this is likely to change much in 2024.