On December 10, 1948, on the heels of history’s most destructive war and the horrors of the Holocaust, the members of the newly created United Nations Organization did something remarkable. They endorsed a bill of rights for humanity, in the form of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The handiwork of Eleanor Roosevelt and a team of talented international experts, the UDHR was a profound development in world politics. It proclaimed that individuals, and not merely sovereign states, were bearers of “inalienable” rights. How a government treated its inhabitants now would be a matter of legitimate international scrutiny.

Seventy-five years later, these accomplishments are at risk. Around the world, repression is rising, authoritarians are exploiting new digital technologies to crush dissent at home and sow misinformation abroad, and violent conflict within and between states has surged, accompanied by widespread violations of international humanitarian law and impunity for perpetrators of war crimes. Existing international institutions are struggling to protect long-established rights and adapt principles of human dignity to novel global threats. Many erstwhile champions of human rights, not least the United States, have proven to be unreliable defenders of freedom. The best way to commemorate this somber anniversary is for human rights proponents to rededicate themselves to Roosevelt’s vision while working to update international mechanisms to contemporary and emerging rights challenges.

A World Reformed

On January 6, 1941, with the Axis aggressors bestride Europe and Asia, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his annual State of the Union address to a still neutral but anxious nation. He pledged to work for a brighter global future founded on “four essential freedoms”: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of religion, freedom from fear, and freedom from want. Although Franklin D. Roosevelt would not live to see fascism defeated, his partner in life and service, Eleanor Roosevelt, would advance that hopeful vision as the first chair of the (then) eighteen-member UN Human Rights Commission, established in late 1946.

For two years, Roosevelt and several brilliant colleagues shepherded these complex and contentious negotiations to produce the world’s first comprehensive statement of human rights. The team’s diverse composition and perspectives refutes the common contention that the declaration is a Western imposition that ignores civilizational and cultural differences, rather than what it actually is: a statement of universal application. Its drafters proceeded from the conviction that there exists one human nature and human condition, and that all individuals possess inherent dignity that must be protected.

Early on, the commission confronted the quandary of whether to draft a legally binding covenant or a nonbinding statement of principles to be endorsed by the UN General Assembly (UNGA). Roosevelt ultimately persuaded her peers to adopt the latter course, confident that a joint declaration grounded in a shared morality would provide the foundation for later formal international treaties. History would vindicate her optimism.

The negotiators’ most impressive achievement was producing a document that could bridge international fault lines and attract global support. This outcome was hardly preordained, at a moment when capitalist democracies and communist countries were consolidating into Cold War blocs and colonial movements were demanding emancipation from their imperial overlords.

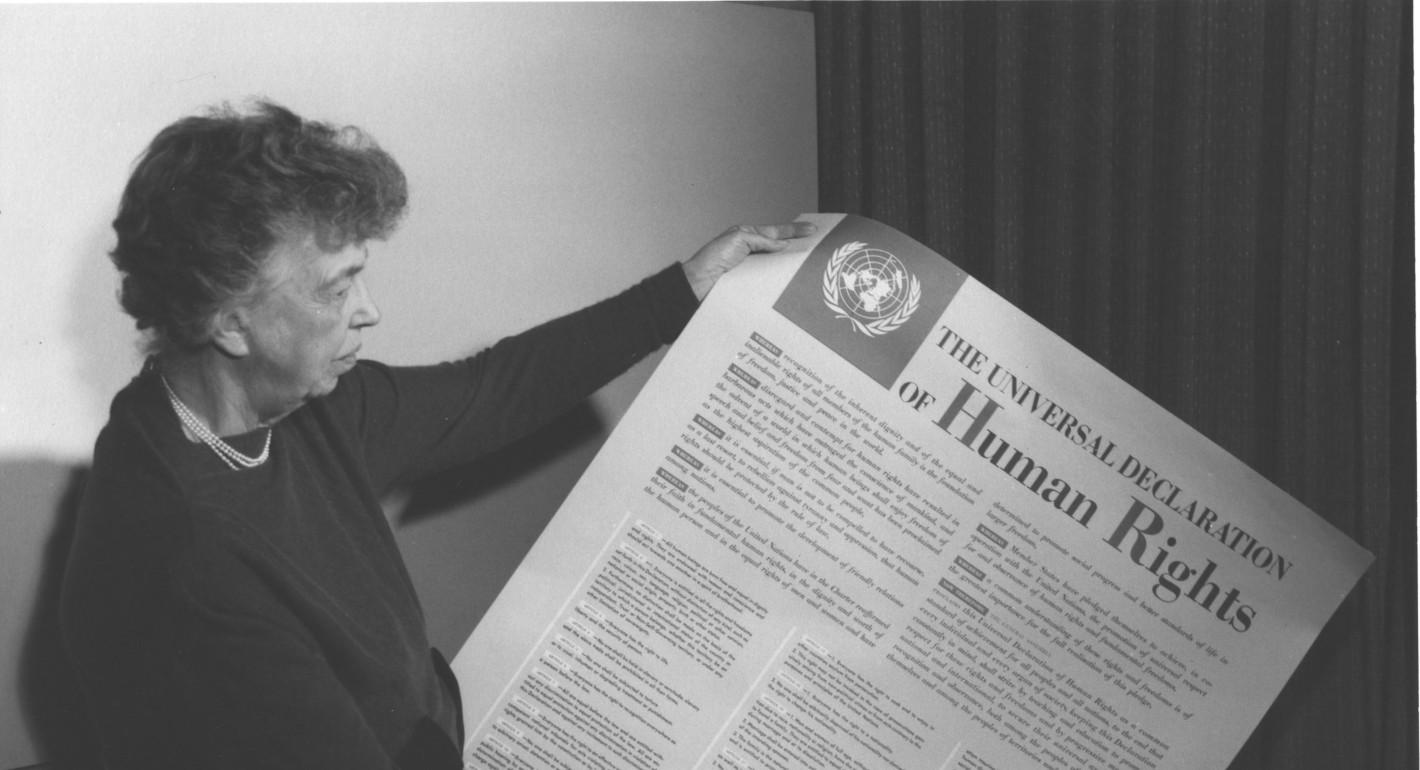

A press conference on the UDHR in December 1948. (Photo by UN/Flickr)

A press conference on the UDHR in December 1948. (Photo by UN/Flickr)

Among the main diplomatic flashpoints was a debate that still resonates today: namely, what priority should the world accord civil and political rights versus economic, social, and cultural rights? Roosevelt herself staked out a pragmatic middle ground, helping ensure that the document UN member states ultimately approved endorsed both the elimination of restrictions on individual liberties (often called “negative rights”) and the provision of capabilities that enable humans to live in dignity (or “positive rights”).

One team member, France’s Rene Cassin, famously likened the declaration to the portico of a Greek temple, replete with a foundation, steps, four pillars, and a pediment. Articles 1–2, the temple’s foundation, establish the inherent equality, liberty, and dignity of all humans and the “spirit of brotherhood” that should bind them. The preamble (the steps) explains why the declaration is needed, contending that “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family” is the “foundation of freedom, justice, and peace in the world.”

Articles 3–27 constitute the temple’s four pillars. The first pillar (Articles 3–11) enumerates core individual rights to life, liberty, equality before the law, and access to impartial justice, as well as freedom from slavery, servitude, torture, and arbitrary arrest or detention. The second pillar (Articles 12–17) enumerates civil and political rights, including to privacy, movement, asylum, nationality, and marriage. The third (Articles 18–21) establishes constitutional liberties, among these rights to thought and religion, opinion and expression, peaceful assembly, and universal suffrage. The fourth (Articles 22–27) enumerates extensive economic, social, and cultural rights, including entitlements to social security, fair employment, education, leisure, and a standard of living adequate for the provision of food, shelter, medical care, and social services.

Articles 28–30, the pediment that holds the entire edifice together, declare that the realization of these human rights will depend on a conducive domestic and international order and on the willingness of individuals to accept mutual duties to cooperate in advancing this agenda.

Hard-nosed realists may be tempted to dismiss the UDHR as a high-minded expression of noble intent devoid of practical impact, but they would be wrong. The declaration disrupted history, by providing standards against which governments could be judged and a banner to which human rights advocates could rally. Around the world, oppressed peoples invoked it to demand independence from colonial masters, to delegitimize racist discourse and institutions (including in the United States), and to confront totalitarian regimes. Many of the declaration’s principles were integrated into national constitutions and domestic legal codes. Globally, the declaration laid the groundwork for no fewer than nine core UN human rights treaties—from the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child—and many other multilateral and regional legal instruments, courts, and bodies.

A System Under Strain

These hard-won gains are in increasing danger, however. A confluence of factors is to blame, but three merit special mention. First, the authoritarians have struck back—with a vengeance. While virtually all UN member states pay lip service to human rights, many routinely violate the liberties of their citizens, and the trend lines are moving in the wrong direction. The world is mired in a democratic recession, now in its seventeenth year. This downward trajectory accelerated during the pandemic, as strongmen exploited the global health emergency to crack down on dissent. Not long ago, many observers naively assumed that the digital revolution would ineluctably expand the frontiers of freedom. Today, autocrats are using surveillance and other technologies to tighten their political grip.

The most powerful authoritarian state is China. Under the absolute control of President Xi Jinping, the ruling Chinese Communist Party has crushed internal political debate, extinguished human rights in Hong Kong, and imprisoned 1 million Uyghurs in concentration camps. Increasingly, China seeks to undermine rights abroad, exporting totalitarian methods to foreign dictators and intimidating critics of its conduct (including among diaspora populations) in the world’s open societies.

To make matters worse, some of the biggest recent declines in human freedom have occurred in established democracies, including the largest—India—and the most powerful—the United States. The Hindu nationalist government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has adopted hard-line sectarian policies and grown intolerant of internal dissent. In the United States, the presidency of Donald Trump from 2017 to 2021 revealed the fragility of the nation’s democratic institutions and commitment to the rule of law. A deterioration of civil liberties has resulted in a downgrading of the United States on major indices of democracy.

Second, violence has surged worldwide, exposing civilians caught in the crosshairs to serious abuses. Mass atrocities and violations of international humanitarian law have become commonplace in conflict zones, including in Gaza and Ukraine as well as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Syria, and Yemen. In Ukraine, Russian armed forces have committed apparent war crimes and abducted more than 20,000 Ukrainian children. In Gaza, Israel has responded ferociously to the massacre of more than a thousand of its citizens by Hamas terrorists, dropping thousands of bombs on the small enclave and killingmore than 15,000 Palestinians—70 percent of them women and children—in the process.

Such outrages expose the hollowness of the international community’s once ballyhooed efforts to create new norms and legal mechanisms prevent atrocity crimes and hold perpetrators accountable, notably the responsibility to protect (R2P) and the International Criminal Court (ICC). R2P, unanimously approved by the UNGA in 2005, commits UN member states to respond when any government makes war on its people or fails to protect them from mass atrocities. That obligation has essentially been abandoned, the victim of perceived selectivity in its application. A similar disillusionment surrounds the ICC. Established in 1998 by the Rome Statute to prosecute genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression, it has never had the support of major powers like China, India, Russia, and the United States, nor has it had any apparent impact in deterring or punishing abuses. Since it began operations in July 2002, it has convicted only ten individuals.

A third impediment is the Janus-faced posture of the United States itself, which dates back to the era of Eleanor Roosevelt herself. Over the past seventy-five years, no country has done more to develop and promote human rights principles and embed these in international law. Yet few have so resisted being bound by multilateral conventions or subjecting themselves to global scrutiny. The United States is the only nation that is not a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, for example, and one of only seven that has not ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. It is not party to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities or the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, as well as other treaties ratified by the vast majority of UN member states.

This ambivalence has multiple sources. One is America’s distinctive rights culture, which prioritizes negative rights (that is, the elimination of restrictions over things like speech and assembly) over positive rights that depend on state intervention or capacities that may not yet exist (for example, the right to a basic income or shelter). Another is the broadly accepted doctrine of American “exceptionalism,” which posits that the United States has much to teach the world but precious little to learn from it. A third is the two-thirds-majority support required for the Senate’s advice and consent to multilateral treaties, a high legislative hurdle to the assumption of binding international obligations, not shared by parliamentary democracies. Lurking behind these influences is a fourth: the widespread, if groundless, suspicion that treaties are inherently antithetical to American sovereignty and the supremacy of the U.S. Constitution. These patterns of exceptionalism (and “exemptionalism”) make the United States an awkward human rights champion.

All of these factors were at play in the early 1950s, when the U.S. Congress nearly passed the Bricker Amendment, a segregationist-inspired piece of legislation to drastically limit the president’s treatymaking power and insulate the nation from UN pressure to provide equal rights to all its citizens. The author of that bill, Senator John Bricker (R-Ohio), is long gone, but his ghost lives on in the reluctance of conservative nationalists to expose U.S. human rights policy to international scrutiny. At the same time, the continued U.S. failure to ensure universal rights at home—evident in the abuses that inspired the Black Lives Matter movement—undermines America’s claims to be their global champion.

Even more damaging to U.S. credibility is America’s selective promotion of human rights abroad, which exposes it to charges of hypocrisy and double standards. All U.S. presidents since 1945, with the exception of Trump, have declared their support for freedom and liberty abroad. And yet all have periodically abandoned those principles to cozy up to dictators, from former president Anastasio Somoza of Nicaragua to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia. The glaring gap between America’s words and its actions calls to mind a quip often attributed to comedian Groucho Marx: “Who are you gonna believe: me, or your own lying eyes?”

Rediscovering Roosevelt

Rather than a cause for despair, the dire state of human rights today should be a call to action. Agnès Callamard, the secretary-general of Amnesty International, frames the choice starkly: “Are we prepared to be a 1948 generation,” determined to transform the course of history, or are we resigned to be “a 1933 generation just looking at the abyss . . . and then all of us falling into it?” The best way to commemorate the UDHR’s anniversary is for human rights proponents to rededicate themselves to Roosevelt’s vision, while working to update international mechanisms to contemporary realities.

Eleanor Roosevelt at a UN meeting in July 1947 (Photo by UN/Flickr)

Eleanor Roosevelt at a UN meeting in July 1947 (Photo by UN/Flickr)

One objective of this effort should be to improve the effectiveness of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC). Established in 2006 to replace the Commission on Human Rights, the UNHRC is the main intergovernmental body charged with defending, strengthening, and reviewing the status of human rights globally. However, it is a flawed organization to which despotic powers are routinely elected. In the United States, Republican administrations have treated it as beyond salvage (“a protector of human rights abusers and a cesspool of political bias,” in the 2018 words of UN Ambassador Nikki Haley). By contrast, Democratic ones have concluded that it is better for the United States to remain inside the tent, fighting the good fight alongside like-minded allies, than to carp from outside while the proverbial foxes run the henhouse.

The Democrats have the stronger case. Despite its problematic membership, the UNHRC has useful mechanisms to monitor and expose gross violations of human rights. These include “special procedures,” such as the appointment of rapporteurs to review specific countries, vulnerable populations, or particular norms. Another is the system of Universal Periodic Review, which obliges members to open their human rights records to external review every 4.5 years. On balance, U.S. President Joe Biden’s presidency has demonstrated the value of U.S. engagement in the UNHRC. Working with a broad group of nations, the administration helped engineer the first UN condemnation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as well as Russia’s expulsion from the UNHRC. The administration has also blunted foreign criticisms of U.S. self-righteousness by conceding weaknesses in the promotion and enforcement of human rights in the United States itself.

Second, defenders of human rights should reaffirm a holistic view of human dignity. Historically, as noted, the United States has adopted a hierarchical approach that privileges “negative” over “positive” rights (a stance the Trump administration took to the extreme). That stance often left the United States in a lonely and churlish position, as the only country voting against resolutions supporting, say, a right to water. The Biden administration has wisely relaxed this position, bringing itself into alignment with the UDHR, which recognizes the interdependent and indivisible nature of these categories of rights. This holistic approach also makes it harder for dictatorships like China to justify crackdowns on civil and political rights by asserting their own version of the hierarchy of human rights, grounded in a culturally or nationally specific interpretation of rights. This more holistic view builds goodwill among developing countries, at a time when many in the so-called Global South perceive the wealthy world as indifferent to their concerns, including their development goals.

Third, defenders of human dignity should work to update existing mechanisms to accommodate evolving conceptions of human rights, as well as to address emerging threats to human rights that were barely anticipated (if at all) in 1948. Among the most pressing imperatives is recognizing and protecting the inalienable rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex people, who currently face severe discrimination and persecution in scores of countries around the globe. The Biden administration, to its credit, has been at the forefront of these efforts, including at the United Nations.

Finally, defenders of dignity must adapt the global human rights regime to new risks, including the deepening environmental emergency and the rapid emergence of AI and other transformative technologies. The world is experiencing a triple planetary crisis of runaway climate change, accelerating biodiversity collapse, and rampant pollution. The inequitable impact of these interlinked trends make it essential to establish a fundamental human right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment, building on recent resolutions in the UNGA and UNHRC. Simultaneously, governments must defend human freedom and dignity against the threats posed by AI and other digital technologies both on and offline—including algorithmic bias, misinformation and disinformation, mass surveillance, censorship, loss of data privacy, and the expansion of digital divides—as well as by advances in biotechnology like genetic engineering and human enhancement.

Eleanor Roosevelt could not have anticipated these and other new dangers to human dignity. Fortunately, the declaration she helped to design and deliver contains universal and timeless principles to apply to them. On the UDHR’s seventy-fifth anniversary, the world should look to her legacy to adapt the revolutionary document to the next century of challenges.