Thousands of young people in the Middle East hit the streets this month to protest against bad governance, corruption, and social injustice. But not just by raising their voices. Some wielded a quieter yet equally powerful tool to demand change and inspire hope—graffiti.

Walking through the city centers of Algiers and Beirut, it is difficult to miss the bold words and imagery that spatter the walls. Some evoke the past to illustrate a long history of suffering, while others use metaphors and name-calling to unite people against their “oppressors.”

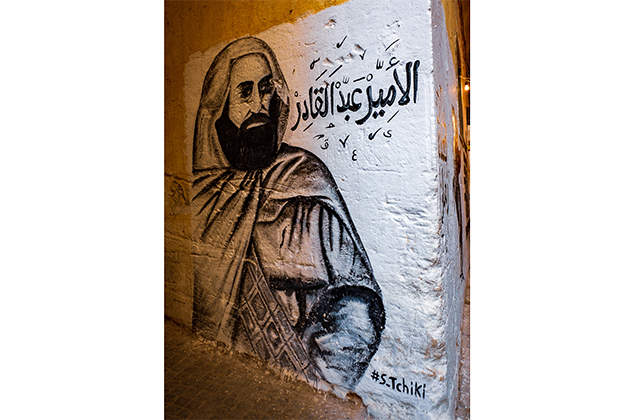

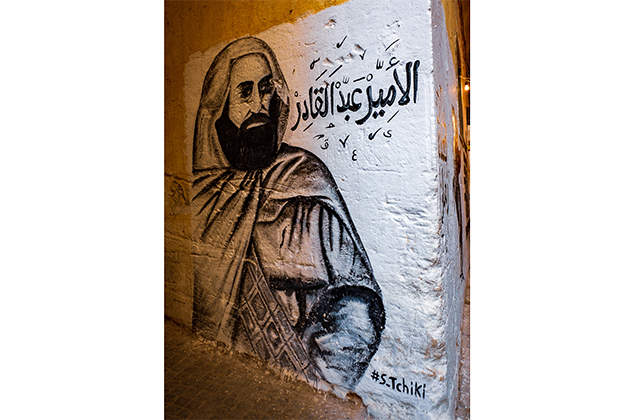

In Algeria, where public space has been severely restricted for decades, graffiti artists seek to arouse nationalistic sentiment. Many portraits and messages hark back to Algeria’s war for independence from French colonial rule. Today’s activists still use symbols from the war’s slogans, heroes, and martyrs.

The Emir Abdelkader, called the Commander of the Faithful, was an Algerian religious and military leader who led the first struggle against French colonialism in the mid-nineteenth century. Photo by Sabri Benalycherif.

Larbi Ben M'hidi, a hero of Algeria’s War of Independence, was a founding member of the National Liberation Front (FLN). Believed to be the mastermind behind the battle of Algiers in Al Casbah, many say that he died after being tortured by French military commanders in 1957. Photo by Sabri Benalycherif.

A slogan of Algeria’s War of Independence, “The only hero is the people,” remains unchanged six decades later and is still the revolution’s motto. Photo by Sabri Benalycherif.

The haik, a traditional women’s garment, is still a symbol of resistance. During colonial rule, many Algerian women wore it despite France’s policy of unveiling in the name of women’s emancipation. The Mujaheedat (female freedom fighters) carried weapons underneath the garment. Photo by Sabri Benalycherif.

A quote by Algeria’s former president Mohamed Boudiaf, “This regime is afraid of clarity like the night’s bird who can only fly in the dark. There won’t be a state until the people become conscious, and the state will emanate from them.” Many Algerians believe that the military was behind his assassination in 1992. Photo by Sabri Benalycherif.

Echaab or “the people” refers to a preeminent body politic or a collective psyche among Algerians. Photo by Sabri Benalycherif.

In Lebanon, the artists seem to use graffiti for emotional expression and to stoke the fires of revolution. Images use political words, quotes, and sometimes insults. Many messages contain swear words and crude language, in an effort to strip their targets (for example, government leaders) of their legitimacy and moral credentials. The art has been made hastily in a moment of anger and disgust against the system.

A young street artist is tagging the word thawra (revolution) on the egg-shaped movie theater in downtown Beirut. This massive, dilapidated structure dates back to 1965 and represents a scar of the civil war (1975¬–1990). Photo by Dalia Ghanem.

“The streets of the revolution: From Beirut to Yemen. Palestine, Iraq, the Amazon, Ecuador, Brazil, Libya.” Lebanon’s protests draw from an international and Arab revolutionary narrative. Photo by Loulouwa Al Rachid.

In Lebanon, some graffiti borrows from fictional characters such as the Joker, an eccentric who aims to upset the social order. Photo by Dalia Ghanem.

“I am an infiltrator. You, dogs of the leader.” Lebanon’s political class dismissed the protesters as infiltrators serving foreign interests. Protesters have retorted that the real infiltrators are the vigilantes sent by political and sectarian leaders. Photo by Loulouwa Al Rachid.

“You revolutionaries of the earth. Julia Boutros, wife of Minister of Defense Elias Bou Saab.” This protester laments that the famous Lebanese singer, Boutros, betrayed her song “You revolutionaries of the earth” by marrying a politician who has never publicly adopted any revolutionary causes and by staying silent during the current mass protests. Photo by Loulouwa Al Rachid.

Yet in both countries, graffiti art subverts state control and takes back the public space. It is difficult to determine the mobilizing or educational effects of graffiti, but perhaps it has been a source of inspiration. Street artists are not the only ones using the written word and images to press for radical change. In Beirut, hundreds of protesters recently hooked pieces of paper onto barbed wire to create a chain of messages that, among other things, demand a technocratic council be formed until elections are held.

Regardless of attempts to quell the protests, the countries’ youth are bypassing institutions, political parties, and ideologies to forge a path to necessary reforms.

Dalia Ghanem is a resident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut and the co-director for gender-related work for the program on Civil-Military Relations in Arab States, where her work examines political and extremist violence, radicalization, Islamism, and jihadism with an emphasis on Algeria.

Loulouwa Al Rachid is an Iraq expert and a former nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center.

Sabri Benalycherif is an independent documentary photographer and contributor to Studio Hans Lucas.