This brief is part of the China Risk and China Opportunity for the U.S.-Japan Alliance project.

Issue Background

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s scheme to boost global connectivity and market integration principally through the export of its infrastructure development capabilities, is redefining Southeast Asia’s economic and security environment. Although the BRI risks the usual pathologies of large-scale infrastructure development—corruption, environmental degradation, social instability, and debt—it also promises an array of economic benefits to the region’s diverse economies, not least by addressing the region’s massive infrastructure deficit and potentially jump-starting industrialization in less developed countries there.

Over the first five years of the initiative, more than $500 billion in BRI-related capital has flowed into Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam alone. Much of this capital comes from Chinese sources for developing transportation links. These links, like the pan-Asia railway network, will connect to Chinese cities—one of the many ways the BRI is weaving the Chinese and regional economies and societies together.

The BRI is a powerful tool of Chinese economic statecraft. As China’s stakes grow in BRI- participating countries, Beijing’s preferences carry heavier weight in the region’s foreign and security policies. China’s pursuit of its own political and strategic agenda is already having divisive effects on intraregional relations related to the South China Sea, including on interactions among members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN); the BRI can be expected to intensify challenges to regional governance. Southeast Asian countries have complex historical relationships with China, however, and they are seeking wherever possible to balance Beijing’s potentially overwhelming influence by diversifying foreign investment and trade and fostering partnerships with allies and international security partners.

In Southeast Asia, the BRI thus presents both risks and opportunities for the United States and Japan. Washington is a vital security partner of most countries in the region, and Tokyo remains the top foreign investor in ASEAN member states. However, as China’s influence grows, both Washington and Tokyo must compete more strategically for Southeast Asian markets, political influence, and military access. To sustain their historical economic and political clout, the allies must reinforce relations with the region through substantial investments in diplomacy, economic development, and regional security.

The United States should recognize and support ASEAN as a key source of a rules-based approach to regional policy that embodies norms closely aligned with those long promoted by Washington and its allies. Japan should seek to sustain its position as the leading source of investment into Southeast Asia and—through its commitment to participating in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a proposed regional trade agreement—reinforce ASEAN’s role as a source of regional governance.

Recent Developments

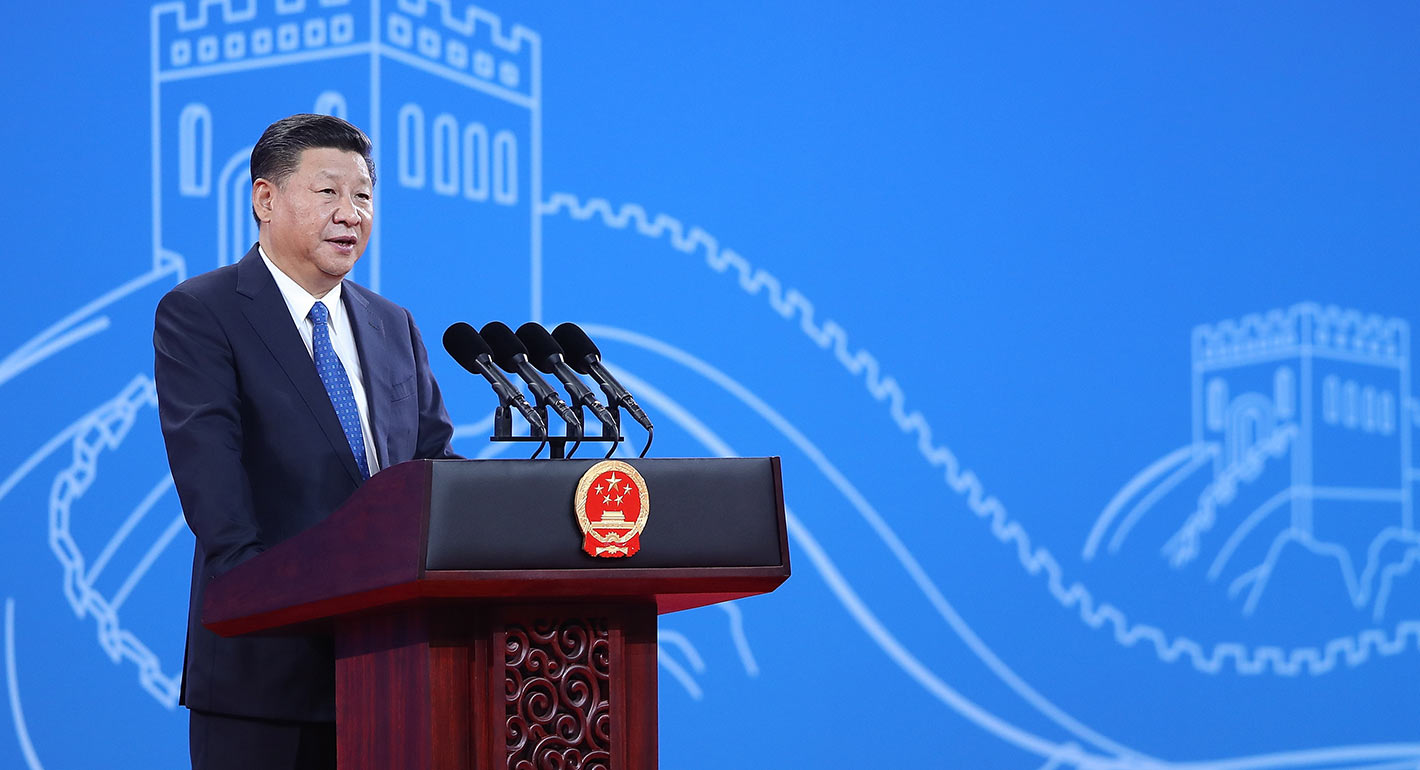

China’s Perspective on the BRI

Southeast Asia’s economic dynamism, its substantial infrastructure deficit, and its strategic location bordering China’s southwestern provinces and straddling key sea lanes in the Asia Pacific have made it a critical zone for the BRI. The initiative enables China to deepen its already expansive ties with the region. China became the region’s top external economic partner a decade ago—both its number one export market and its top import partner since 2009. Imports from China include intermediate goods for regional production networks and consumer products. Six Southeast Asian states—Cambodia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam—are among the ten countries most connected to China via trade.

In 2014, China upgraded its free trade agreement with ASEAN to further integrate with the region economically. The conclusion of RCEP, a trade arrangement that encompasses all ten ASEAN members as well as other ASEAN partner states, will expand trade between China and the region further still. Beijing’s regional economic ties are also facilitated by informal networks between China and the region’s powerful ethnic Chinese business communities.

The BRI has also broadened the use of the renminbi by ASEAN members. Although China has had currency swap agreements with several Southeast Asian states for nearly a decade, monetary cooperation between the People’s Bank of China and national banks in the region is also expanding. In November 2018, for example, the People’s Bank of China signed a $28.8 billion currency swap agreement with Bank Indonesia, located in Southeast Asia’s largest economy, helping to stave off the collapse of the rupiah. In January 2019, Beijing published a plan by thirteen Chinese government agencies—including the country’s central bank, foreign exchange regulator, securities watchdog, and the Ministry of Finance. The plan aims at promoting financial integration between southern Guangxi Province and Southeast Asia by 2023 through cross-border trade settlement, currency transactions, investment, and financing in the renminbi.

Beyond that, the BRI helps address China’s long-standing security concerns about U.S. encirclement and maritime chokepoints. Former Chinese president Hu Jintao highlighted these concerns when he referred to the so-called Malacca dilemma, or China’s heavy dependence on the unimpeded passage of as much as 80 percent of its oil imports through the Straits of Malacca.

A substantial share of BRI investment in transport and logistics has gone to building or expanding harbors and port facilities. This has increased Chinese stakes in port management and port construction across the region, including in the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville on the Gulf of Thailand, Malaysia’s Melaka Gateway on the Straits of Malacca, and Myanmar’s port of Kyaukpyu on the Bay of Bengal. These ports serve China’s massive fleet of commercial and fishing vessels. Where the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is granted access, the ports also enhance China’s capacity to refuel and resupply naval vessels.

The BRI also supports Chinese economic growth and provides opportunities to internationalize key industries. Generally, the initiative helps invigorate China’s slowing growth in part by increasing opportunities for the country to boost returns on investment, utilize its excess industrial capacity, and boost employment in its massive construction sector. In addition, China’s economically lagging, landlocked southwestern provinces have long had a vision of connecting to Southeast Asia and its ports via roads and rails.

Moreover, the BRI expands opportunities for Chinese infrastructure companies. These mainly state-owned enterprises have been operating in Southeast Asia since the early 2000s, with substantial involvement in the development of natural resources in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. China’s policy banks—principally the China Development Bank (CDB), the Export-Import Bank of China, and special funds established for the purpose of BRI lending, such as the Silk Road Fund—play a key role in project financing. Their lending dwarfs that of other sources, including the Chinese-initiated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), other multilateral development banks, and commercial lenders.

Beijing has sought to use the BRI to expand the use of China-produced information technology equipment in the region as part of an envisioned Digital Silk Road. In addition to developing the China-ASEAN Information Harbor for comprehensive cyberspace exchanges, Beijing is seeking to expand networks of fiber optic cables, mobile structures, and other digital links in the region, diversifying cable networks and accelerating a tilt away from U.S. suppliers. China also aims to promote the use of its indigenous global navigation satellite system, the BeiDou Navigation System. Finally, Chinese firms, such as Huawei, are investing in the development of 5G networks and cloud computing for regional markets, while Chinese e-commerce giants like Alibaba have begun providing e-payment services throughout the region.

Southeast Asian Perspectives on the BRI

For the most part, Southeast Asian countries have welcomed the BRI since China launched it in 2013. The World Bank sees substantial potential for the initiative to have positive impacts on regional trade, cross-border investment, the allocation of economic activity, and inclusive growth—including poverty reduction. Policy reforms and cooperation in the region will enhance these positive effects. As a source of economic stimulus, the BRI will help keep the region on track to become “the fourth largest economy in the world” by mid-century.

The BRI also offers resources to help the region make progress toward realizing its infrastructure development goals. As reflected in the 2010 Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity, these goals predate the launch of the BRI. The region’s BRI-participating countries also have their own national infrastructure-development plans, such as Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor, Malaysia’s Logistics and Trade Facilitation Master Plan, Indonesia’s ambition to become a “global maritime axis,” and Myanmar’s National Transport Master Plan.

Yet not all countries in Southeast Asia have fully embraced the BRI. In 2018, for example, Malaysia canceled several Chinese-financed projects and temporarily suspended a number of other such infrastructure projects, after newly reelected Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad denounced them as “unequal treaties.” And although the Philippines has seen the BRI’s potential to help address its infrastructure needs (which are laid out in a program called Build, Build, Build), Manila—which has unresolved maritime disputes with Beijing—has been slow to pursue projects. Likewise, Vietnam harbors concerns about the BRI’s Maritime Silk Road, a route that passes through the South China Sea (which Vietnam calls the East Sea), where Hanoi too contests China’s expansive maritime claims; these tensions have made Hanoi wary of meeting its huge infrastructure development needs through the BRI.

There are other signs that regional actors are hedging against a China-centric economic order. Japan and several ASEAN countries have joined the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), to which China is not party. The passage of the multilateral trade agreement, which lowers tariffs among eleven countries—Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam—indicates that regional members will develop alternatives to China-centric supply chains.

The region’s somewhat cautious embrace of the BRI and the potential influence of the CPTPP on China’s role in regional supply chains matter. These developments show that the BRI is only one among many factors influencing economic patterns as well as foreign and security policy choices in the region. But the BRI is, without question, amplifying Beijing’s influence there, altering the international calculus of a region that for decades has favored the United States and its allies. Trade volume between China and ASEAN reached a record high in 2018, and it has since continued to rise. In addition, the BRI has raised the relative share of Chinese FDI into the region. Although Japan remains by far the top source of FDI for Southeast Asia, Chinese FDI is flowing rapidly into ASEAN’s less developed economies, including into infrastructure.

After visits by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and President Xi Jinping in 2018, the Philippines appears poised to accept Chinese aid to develop the port of Davao as an extension of the Maritime Silk Road, despite its sovereignty dispute with China. Likewise, in late 2017, during Xi’s visit to Vietnam, Beijing and Hanoi signed a memorandum of understanding to promote bilateral connectivity, even though they are locked in an ongoing maritime dispute. As economic ties grow, some countries in the region are buying more Chinese military equipment, including traditional U.S. customers like Malaysia and Thailand.

The Stakes

Economic Dimensions

The BRI is designed to create an interconnected hub-and-spoke economic system emanating from China. As one economist observes, some smaller countries worry about the risk that the BRI will lead to Chinese dominance in their economies and that, rather than boost their own economic development, the initiative could crowd out their manufacturing sectors.

The BRI, moreover, helps already massive Chinese multinational companies grow larger still, especially in such sectors as infrastructure development. The heavy presence of these state-owned enterprises in the regional economy risks undermining principles like nondiscrimination and respect for market principles.

The absence of transparent, uniform lending standards for BRI projects also carries macroeconomic risks, specifically in the sense that project lending may be increasing sovereign debt risks to unsustainable levels in the poorest participating countries, including Cambodia and Laos (which is at especially high risk). The estimated cost of Laos’s section of the Kunming-Singapore Railway is approximately $6 billion—almost two-fifths of the country’s 2016 GDP. Laos is among the countries a report by the Institute for Global Development assessed is at high risk for debt distress. Cambodia has also seen its debt to China accumulate rapidly, an amount that now totals nearly 50 percent of the country’s debt to foreign donors, although there are no current signs that Cambodia is at high risk of debt distress.

Political Dimensions

China’s expanding trade and investment ties in ASEAN make it a major stakeholder in a region where Beijing also pursues contentious national interests with respect to maritime rights and sovereignty in the South China Sea. China is likely to use its influence to promote its regional interests, as it did in 2012, when Cambodia—a favorite target of Chinese aid and investment— used its position as ASEAN chair to block efforts to include references to disputed South China Sea territory. As a result, the ASEAN meeting failed to produce a joint statement for the first time in the bloc’s forty-five-year history.

In BRI-participating countries—particularly those where China is the dominant economic player, such as Cambodia and Laos—greater Chinese influence risks reinforcing authoritarian governance and reducing progress on human rights and transparency. China’s export of its big data computing and artificial intelligence technologies to create a Digital Silk Road could reinforce these trends by offering powerful surveillance tools to participating states, such as Laos, which was among China’s partners in launching this digital endeavor. Other concerns about BRI projects across the region include the environmental repercussions, the potential to increase transboundary crime and corruption, and the disruptive impact on local communities, which may or may not have their interests and rights protected by national laws.

Moreover, China has framed the BRI as a Chinese contribution to global and regional public goods, including by fostering free trade, international development, and governance that is more inclusive of developing countries. The perception among many in the region that the United States is less willing or able to supply global and regional public goods has strengthened the appeal of China’s message. Over the long term, this state of affairs could undermine the credibility of U.S. leadership in the region.

Xi has also claimed that the BRI is a source of “new ideas and plans for reform of the global governance system.” The AIIB, established to help finance the BRI (although in practice its BRI-related lending has been modest to date), drew its principles from established multilateral development banks. It is less clear to what extent other new mechanisms associated with the BRI will integrate or reject established modes of global governance. For example, Beijing has issued regulations to establish international commercial courts that are based in China and that function within the existing hierarchy of Chinese courts; this arrangement appears to be aimed at providing international dispute resolution services for BRI-related projects. Uncertainty persists around whether these China-based courts will exercise exclusive jurisdiction over cases involving BRI-related disputes and how these courts will relate to other international commercial courts and arbitration centers.

Finally, China’s port construction can be seen as part of an emerging global Chinese security architecture. Guaranteed port access across the region will enable Beijing to not only better protect commercial shipping lanes and critical energy flows—and engage in antipiracy, humanitarian, and disaster relief operations—but also facilitate a more active Chinese military presence in the region. It remains unclear how China’s military might play a role in protecting Chinese BRI investments and citizens involved in BRI projects. Some assessments expect that People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops as well as Chinese paramilitary forces could soon operate overseas alongside private contractors, a development with implications for the interests of the United States and other military actors in the region. In addition, large-scale investments and the presence of more Chinese citizens working and living abroad in conjunction with BRI projects could drive growing demand for expeditionary capabilities in the future.

Potential Risks

For the United States, the BRI thus poses a number of economic, political, and security risks, especially because the initiative has developed amid growing concerns among ASEAN states about the credibility and depth of the United States’ commitment to the region. This increases the likelihood that some countries may choose to bandwagon with China, or otherwise hedge against a weaker or less engaged United States.

The economic downsides of the BRI for the United States are exacerbated by aspects of U.S. economic policy toward Southeast Asia. Although countries in the region generally welcome the opportunity to develop close ties with the United States to balance against China’s growing influence, Beijing’s well-developed and persistently enunciated plans for significant long-term investments in the region contrast with perceptions of U.S. inattention or incoherence. Four ASEAN countries supported the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and moved forward with a new version of the agreement, the aforementioned CPTPP. The decision of U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration to terminate U.S. participation in the TPP remains a source of misgivings in the region. Southeast Asian states are also concerned that the United States will seek to address its regional trade deficits by pursuing bilateral deals with each country and that Washington may ask regional states to make more military contributions to support U.S.-led objectives.

In addition, the BRI poses potential challenges to U.S. commercial interests in the region. Crucially, the initiative is providing China with the opportunity to develop and export standards for a range of technologies, not just in infrastructure and transportation systems but also in areas in which the United States has sought global leadership, like artificial intelligence.

Meanwhile, Beijing’s efforts to use the BRI as an avenue to increase international use of China’s currency, the renminbi, is characterized by some as “currency statecraft.” The United States wishes to preserve dollar dominance, but the BRI is helping move the international monetary system in the opposite direction.

Chinese-initiated institutions and fora—such as the AIIB, the RCEP, and the BRI—strengthen Chinese influence on governance mechanisms in Southeast Asia, potentially reducing the weight of more established institutions, such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB), which counts the United States and its allies among its longtime stakeholders. In addition, as China has shown itself willing to weaponize its economic influence to promote its regional interests, like when Beijing restricted imports of bananas from the Philippines in 2012, when Manila sent its navy to confront Chinese fishing vessels at Scarborough Shoal. China’s growing economic power in the region could thus exacerbate tensions within ASEAN.

These developments all are weakening the relative influence of the United States, as well as the impact of institutions that have been positive forces for international law and an open trading system in the region. Strong U.S. relations with ASEAN are important for encouraging the bloc to pressure China to follow international maritime law with regard to disputes in the South China Sea and to resist its further militarization of Chinese-controlled islands.

As China’s regional ties expand and deepen through the BRI, the country’s military cooperation with some BRI-participating countries may also grow, complicating U.S. security interests and the U.S. military’s ability to project force in the region. Southeast Asian states are already major customers for Chinese military hardware, and trends suggest China is on track to become the leading source of weapons for the region, which is currently an important market for U.S. military equipment.

As for Tokyo, the BRI could become a vehicle for limited cooperation with Beijing, but it is principally a source of intensifying competition between the two countries in the region. The development and security plan launched by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2016, which emphasizes the development of high-quality infrastructure alongside overt security cooperation, offers an alternative vision. Japan’s long track record as an investor and provider of development assistance in Southeast Asia, bilaterally and through the ADB, gives this approach regional appeal. At the same time, however, despite Tokyo’s extant commitment to pacifism, its history risks prompting Beijing to denunciate this overture as a new co-prosperity sphere—a description some detractors have applied to the BRI.

While offering an alternative to Chinese investment, Japan has expressed willingness to cooperate with China on projects under the BRI umbrella under certain conditions, including openness and transparency. This mind-set could help the countries avoid wasteful competition like that which occurred in Indonesia over a high-speed rail line. However, there are also risks that strategic tensions between Japan and China could politicize projects with costly outcomes for all parties.

Moreover, cooperation between Tokyo and Beijing on infrastructure development faces domestic Japanese problems, such as a lack of interest from Japanese companies. For example, the media highlighted a plan to connect three airports in Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor via high-speed rail as an example of Japanese-Chinese cooperation in third countries. However, Japanese companies chose to withdraw from the plan, and the project can no longer be regarded as an example of such cooperation. This challenge facing Japanese cooperation with China stems not from political or security affairs but rather from a reluctance on the part of Japanese companies to invest due to concerns about profitability.

Potential Opportunities

In Southeast Asian capitals, the sheen has begun to wear off Chinese BRI investments, and participating countries have begun reassessing their agreements with China. For example, in April 2019, after the Malaysian government temporarily suspended plans to develop an East Coast Rail Link with Chinese financing, Kuala Lumpur renegotiated the terms of the deal with Beijing; China lowered the construction costs to $14.4 billion, agreed that a fifty-fifty joint venture would operate the line, and expanded local participation in the construction work. The resulting agreement reduced the amount of loans provided by Beijing. This is an example of how Southeast Asian countries’ growing concerns about aspects of the BRI have led to certain changes to China’s commitments. Myanmar has also reduced the scale of the planned Kyaukpyu port project due to concerns about excessive debt.

The United States has an opportunity to use the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) concept to coordinate its economic and security strategies in the region with Japan, as well as with other allies like Australia and crucial partners like India. Washington, for example, can leverage its financial commitment through the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act. This law can be an impetus to invest in regional sectors like technology, energy, and infrastructure, in turn strengthening the role of private capital, ensuring high quality development standards, and coordinating development with partners through FOIP to maximize their impact. FOIP also offers a framework through which to coordinate BUILD Act investments with Japan’s Expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, alongside Indian and Australian plans for Southeast Asian infrastructure projects, as well as the European Union’s strategy for connectivity in Asia.

The United States can enhance its status in the region and champion high technical, social, and environmental standards by better utilizing its unique intellectual capital and expertise. In one recent example, a review of Myanmar’s BRI port development project by U.S. economists, diplomats, and lawyers was reportedly key to Naypyidaw’s efforts to renegotiate for improved terms with its Chinese partners.

Southeast Asia will welcome support for strategic independence as regional actors participate in the BRI. In this sense, the region’s closer economic ties with China may encourage states to seek closer security ties with the United States. Polls show that popular views of China’s growing influence are mixed across the region, as generally low levels of trust co-exist with more positive views of the benefits of China’s economic role. The variation in perspectives about the costs or benefits of China’s influence appears correlated with the level of political tensions between China and countries in the region, as countries with the least favorable views of China tend to be those locked in maritime disputes with Beijing.

Regional connectivity also creates new opportunities for transnational crime in the region. In particular, the BRI could create new modalities for trafficking in drugs, wildlife, and people, with potentially destabilizing effects. Washington can also reinforce its role as the preferred provider of regional public goods by sustaining its prominent role in combating the region’s numerous nontraditional security threats. Through high-level participation in regional summits, the United States can underscore its commitment to the region and to ASEAN, which has been so critical to fostering regional independence and cohesion. Although Trump did not attend the East Asia Summit or the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in November 2018, he did go to the 2019 G20 summit in Osaka, Japan, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo attended an August 2019 ASEAN summit.

Japan, meanwhile, remains the leading source of investment into Southeast Asia, the largest economy in the CPTPP, and a key economic actor in RCEP. Tokyo is well placed to continue to expand its regional economic role in ways that will prevent the region from becoming uniformly oriented toward China. Japan remains the dominant source of infrastructure investment in Asia with a reputation as a source of reliable financing and quality development. And, for the region’s CPTPP members, Tokyo’s leadership in negotiating the agreement has strengthened Japan’s image as a reliable economic and diplomatic partner. Japan’s role with India in the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor also offers an alternative to the BRI or at least an additional source of development financing—public as well as private—and creates additional new links between Asia and East Africa. At the same time, Japan’s commitment to participating in RCEP, alongside all the ASEAN members, can be seen as supportive of ASEAN centrality, or efforts to help the bloc remain a central force for the development of regional governance.

Japan is well equipped to encourage coordinated bilateral engagement with the United States in the region by promoting a shared vision of regional cooperation through the common vision of FOIP. With its deepening relationship with India and strong ties to Australia, Japan can play an important role in enhancing regional security cooperation within the limits of its pacifist constitution against China’s growing military footprint. Japan’s security legislation of 2015 expands the range of activities in which Japan’s military can engage, such as providing noncombat logistical support for the U.S. Navy and defending U.S. naval vessels and aircraft.

It is important to note, however, that it is unclear to what degree Japan, the United States, and other major countries (Australia and India) agree on the strategic direction of the FOIP framework. The concept is seen by some as principally a way to conceptualize a new maritime agenda among a broader array of strategic partners than the United States and its formal allies to counter China’s maritime ambitions. Others see it as a potential basis for a formalized set of mutual obligations among major powers in the region to reinforce norms supportive of liberal political values and the rule of law.

Next Steps

The BRI remains protean, and Southeast Asia is among the world’s most politically and economically dynamic regions. Significant uncertainty therefore remains regarding the risks and opportunities attendant to BRI projects there. This uncertainty, however, can be lessened through targeted study of three areas in particular:

- Assessing and addressing the goals of partners and allies: What do U.S. allies and strategic partners in Southeast Asia want from strengthened U.S. and Japanese roles in the region, given the risks and opportunities inherent in the BRI? How do these regional goals relate to U.S. and Japanese interests? How can the United States and Japan cooperate to address these interests?

- Assessing risks: What are the risks, opportunities, and implications of cooperating on regional infrastructure projects with China for the United States and Japan separately and in tandem?

- Identifying areas of comparative advantage: How might the United States and Japan better compete with China in the area of emerging technologies?

About the Authors

Carla P. Freeman directs the SAIS Foreign Policy Institute and is concurrently associate research professor in China Studies. She conducts research on Chinese foreign and domestic policy with a current focus on regional dynamics, including China and its periphery, nontraditional security, and China’s role in international organizations.

Mie Ōba is a professor at Tokyo University of Science who specializes in international relations with a focus on regionalism and regional integration in Asia. She holds a PhD in international relations from the University of Tokyo.