Two and a half years after Minsk II was signed with the aim of ending the conflict in eastern Ukraine, the accord has yet to produce substantial results. The Minsk process is running out of steam, not least because Russia has no intention of delivering on its commitments regarding Ukraine’s security. With both Berlin and Paris involved in the Normandy format talks with Ukraine and Russia, the election of Emmanuel Macron could help solve today’s deadliest conflict in Europe. But for that to happen, the French president must be more ambitious.

In Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region, things are getting worse. Instead of the pledged ceasefire and withdrawal of heavy weaponry, there is creeping Russian escalation. From February to May 2017, the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine recorded a 48 percent increase in conflict-related civilian deaths compared with the previous three months.

Russia is digging in: it has allowed the self-proclaimed people’s republics of Luhansk and Donetsk to adopt the Russian ruble as their currency and expropriate Ukrainian businesses. Moscow has also started to accept documents issued by its proxies, such as birth or marriage certificates and car license plates. Simultaneously, a series of killings targeting senior Ukrainian intelligence officers indicates a strategy of decapitation by Moscow. Many experts also point to Russia as the source of recent large-scale cyberattacks that have paralyzed Ukraine’s government and energy and banking sectors and have spread across Europe.

All of this puts Kyiv in a difficult position. Despite strong populist and nationalist forces, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko pursues important if not always popular reforms. But he is under pressure from his international interlocutors to deliver Ukraine’s part of the Minsk II accord, such as greater autonomy in Donbas, where local elections are meant to take place. Yet without a sufficient improvement in security, elections in the region would be a repeat of Crimea’s referendum at gunpoint in March 2014, when the recently annexed peninsula voted on whether to become part of Russia. No European leader would commit such political suicide.

Despite this dangerous escalation, EU responses have remained broadly the same: rolling over the travel bans and sectoral sanctions imposed on Russia in 2014. While the U.S. Congress resolutely supports Ukraine, it is not clear what the current policy of the U.S. administration is toward Russia. The inertia in the West’s Russia policy—whereby Russian escalation is met by more of the same from Europe—means Europe now faces the real prospect of the mother of all frozen conflicts on its doorstep.

With the May 7 election of Macron in France and a revived Franco-German motor, there is now an opportunity to reboot the Minsk process. Macron knows better than most incoming presidents how his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin operates, having experienced Moscow’s interference firsthand in the French presidential election. Still, Macron has avoided direct attacks on the Russian president, perhaps generating an opportunity for France to step in as a more neutral broker.

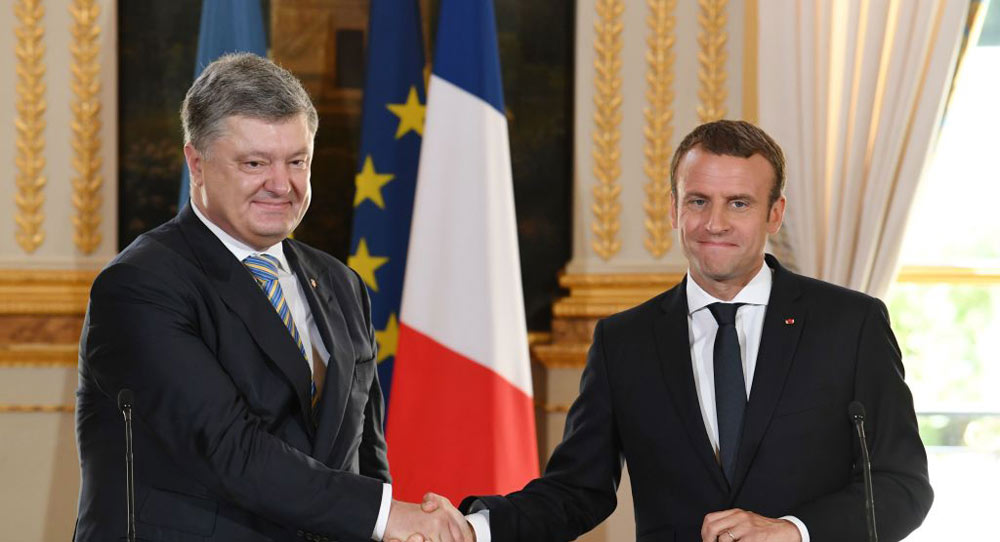

The French president said during a meeting with Poroshenko that he wanted to apply the Macron method to Minsk: small but concrete steps to see progress very soon. For Paris, the key is to make all sides more accountable to their actions on the Donbas contact line that divides Ukrainian government forces and Russian-backed separatists, by expanding the observer mission of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).

While well-intentioned, this approach is likely to fail to change Putin’s calculus because the Russian president has little incentive to move on withdrawing forces—incrementally or not. To force a rethink in Moscow, Macron needs to push for bolder steps.

First, he should begin to discuss with Berlin and Washington a beefed-up international presence to actively monitor and enforce a ceasefire on the contact line. The current OSCE mission has brought limited results, as its members are carrying out a difficult job with a limited mandate and resources.

Second, Macron can signal that the EU will toughen its Russia sanctions if there is no goodwill from Moscow by the time of the measures’ next renewal in January 2018. Stronger sanctions should target those involved in expropriating Ukrainian businesses in the east and those committing human-rights abuses in Crimea. The duration of the measures should be extended to twelve months from the current six. In addition to signaling resolution, annual renewal would end self-defeating squabbles in the European Council or the Council of Ministers, where one or two more Putin-friendly nations threaten to upset the apple cart.

The efforts to change Moscow’s calculus should be accompanied by bolder support for Ukraine. The country seeks a European future. The recent free-trade agreement with the EU and visa liberalization for Ukrainians traveling to EU countries have been hard won, following Kyiv’s ambitious reform program. However, other reforms in Ukraine have been less popular, and with presidential and parliamentary elections coming in Ukraine in 2019, the EU cannot rely on inertia to keep reforms on the road and European dreams alive.

With EU membership for Ukraine unrealistic for the time being, Macron should propose another visible milestone that Ukrainian reformers could work toward, such as the EU customs union or the country’s eventual membership of the European Free Trade Association. Both options would multiply the EU’s transformative effect in its neighborhood and brandish Macron’s pro-European credentials.

These actions would show Putin that Macron is serious about supporting Europe’s neighbors, which form an indivisible part of the European project championed so eloquently by the French president.

Fabrice Pothier is the director of Rasmussen Global’s Ukraine Project. As part of the project, Rasmussen Global has published a paper on why Ukraine should be a priority for Macron.

.jpg)

.jpg)