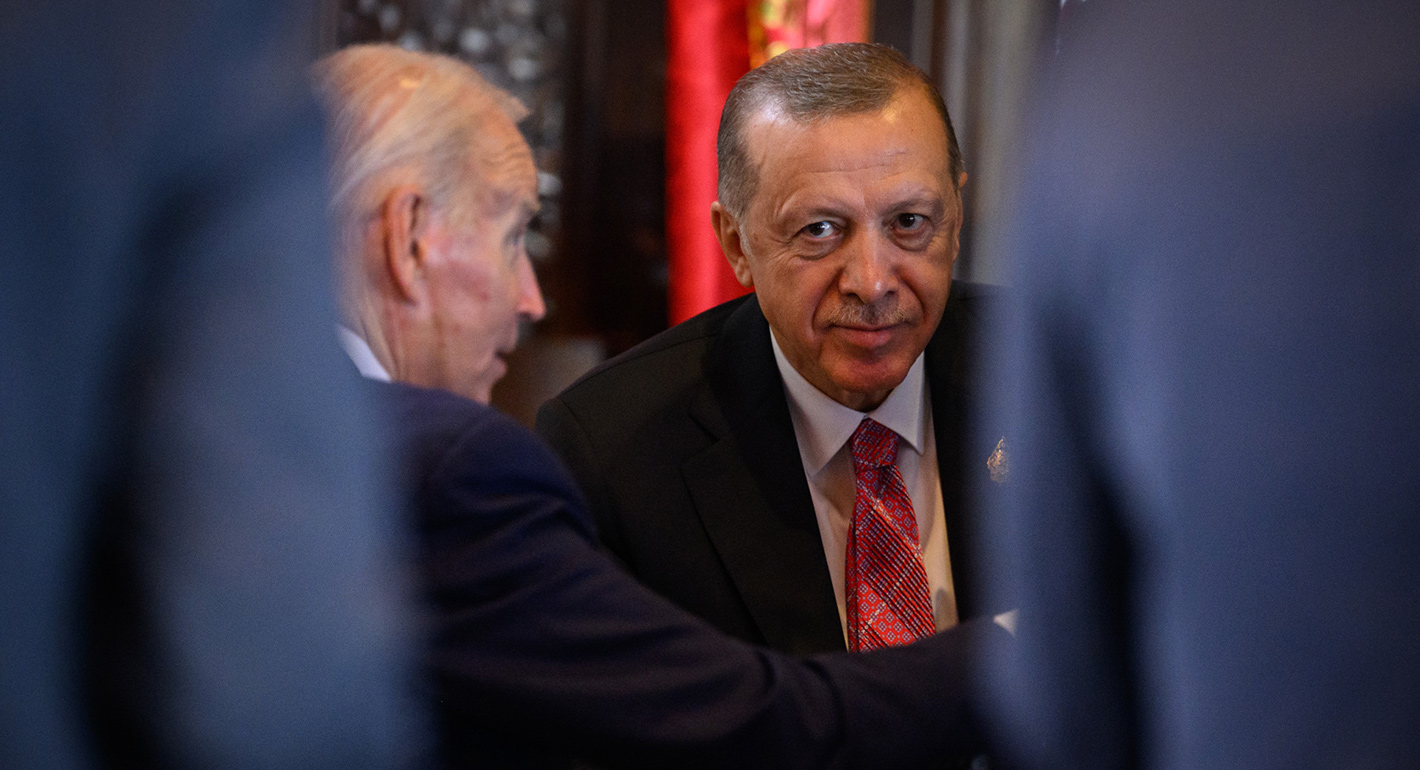

Türkiye and the United States just made an unforced error. The wavering partners mutually resigned to postponing their much-anticipated White House rendezvous this week between U.S. President Joe Biden and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. This delay followed a period of mixed messaging, including a U.S. assertion that no visit had been scheduled, which contradicted joint preparations in the background and, more importantly, raised eyebrows on the Turkish side.

The visit, the first of its kind between the two countries during the Biden administration, was supposed to symbolize a turn for the better in relations—an expectation now rendered less conspicuous. If Türkiye and the United States want to maintain momentum, they need to quickly recover from the negative fallout. The July NATO Summit in Washington provides the right opportunity to do so.

Unscheduling a Difficult Encounter

The stated reason for the postponement was scheduling difficulties, but that was more likely an attempt to conceal more serious differences, such as misaligned expectations and irreconcilable policy choices.

The contrast between Biden’s continued support for Israel, including his approval of a military aid package, and Erdoğan’s increasingly harsh rhetoric against the war in Gaza, as well as his meeting with Hamas leadership in Istanbul, presumably complicated the timing of the meeting. Then, Türkiye decided to halt trade with Israel, which set it further apart from the United States.

The question now is where the postponement leaves the distressed partnership, which had been on an upward trajectory since Türkiye’s ratification of Sweden’s NATO accession bid and progress on the U.S. sale of F-16 fighter jets to the Turkish Air Force. Although the prospect of a Biden-Erdoğan handshake at the White House before the November U.S. presidential elections seems next to impossible, Ankara and Washington should consider ways to arrest negative speculations and diminish the space for disruptive hard-liners on both sides to object to a realignment of the relationship.

The April 29 meeting between U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and his Turkish counterpart, Hakan Fidan, on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum in Riyadh was one example of maintaining a semblance of positive inertia. The U.S. trade delegation’s visit to Ankara the next day, which revived a format for talks on updating the bilateral trade and investment framework, portrayed a similar image. In May, the American-Turkish Conference in Washington brought together officials and business circles from both countries. Such engagements imply that the frictions that led to the aborted presidential-level meeting are not preventing engagement at other levels.

Piggybacking on NATO’s Washington Summit

The prevailing, shared desire to improve relations is where the logic of a well-choreographed meeting between Biden and Erdoğan during the NATO Summit in Washington comes into play. The summit is probably the most convenient way to walk back the image of high-level disengagement and instead project presidential endorsement of the need for improved bilateral relations. The 2021 meeting between the Turkish and American presidents, the first after Biden’s inauguration, also took place on the sidelines of the NATO Summit in Brussels and had largely succeeded in creating an upswing in relations. This experience should be repeated, if possible.

Of course, replicating that success, especially for a meeting on the sidelines of another event, is neither easy nor guaranteed. Instead of focusing on long-standing disagreements, the meeting should be designed to showcase the two sides’ shared determination to advance bilateral relations through deepened cooperation in key areas of convergence. These areas include trade and investments, energy, and defense and security.

The United States ranks among Türkiye’s top five trade partners, and informed experts have noted the potential for growth in Turkish-American trade and investment ties. Renewing the more than twenty-five-year-old bilateral Trade and Investment Framework Agreement would strengthen the institutional foundation for these types of economic activities. Should progress be made in related talks (including a stable, upward trajectory in political ties), bilateral trade and investment figures could indeed go up—benefiting both countries.

The energy sector is another promising area of cooperation, with proven results. American liquified natural gas (LNG) exports to Türkiye spiked in 2022, and despite a small decline in 2023, they could increase again in future years. Ankara and ExxonMobil are close to finalizing a multibillion-dollar deal for the long-term provision of 2.5 billion cubic meters of U.S. LNG annually to Türkiye. Meanwhile, cooperation in civilian nuclear energy, including conventional and small nuclear reactors, is also on the agenda. Turkish private enterprises have already shown interest in partnering with the United States on small reactors—an untapped potential for collaboration. Türkiye’s strong manufacturing capacity and the mostly long-term presence of more than 1,000 U.S. companies—including those with strong energy portfolios—create a solid basis for collaboration on energy transition projects both within Türkiye and in third countries. Türkiye’s production of critical energy transition input items, such as solar panels and wind turbines, could jointly be increased, which in turn would offset overreliance on China in this sector. There is also the potential for joint energy transition projects in Africa, where Türkiye has considerably increased its footprint and influence over the years and the United States is showing more interest.

Defense industry cooperation had historically acted as the main catalyst in the partnership, but that is no longer the case. Deteriorated relations have eroded the culture of defense cooperation, with political disagreements inhibiting arms sales to Türkiye. Sanctions and Türkiye’s exclusion from the F-35 program have created additional setbacks. U.S. companies remain reluctant to do business with their Turkish counterparts even in unsanctioned areas, simply out of an abundance of concern that they could inadvertently become subject to penalties.

Although this toxic environment in defense cooperation still prevails, the F-16 deal earlier this year was the first sign of a potential return to normalcy. Then, in March, Blinken and Fidan discussed, among other things, “opportunities to transform the U.S.-Türkiye security and defense relationship,” including a U.S.-Türkiye Defense Trade Dialogue. These objectives represented an ambitious and forward-leaning determination to rebuild defense industry ties. Biden and Erdoğan can add force to this direction by embracing this important vision.

Some may argue that prospects for bilateral cooperation with the United States may be diminishing, as Türkiye’s bustling defense industry transforms the country “from client to competitor,” as outlined in a new report by the International Institute for Strategic Studies. But it is precisely because of Türkiye’s recent advancements in defense industry that Ankara and Washington have growing potential to widen their cooperation in this sector, enhance their trade ties, and build strong and new synergies in related technologies. This is especially true in today’s securitized global landscape.

The same argument can be made regarding the need for Türkiye and the United States to work closely in the face of constantly evolving geopolitical challenges. On Russia’s war against Ukraine and the related issue of security in the wider Black Sea area, for example, Ankara and Washington are both better off being aware of each other’s interests and prioritizing joint and coordinated action. This is the case even if they do not always see eye to eye.

A Blessing in Disguise

The postponement of Erdoğan’s visit to Washington may be a missed opportunity, but at this point, treating the delay as a blessing in disguise is likely the smart move. Now, bilateral relations must be kept on track and opportunities for looking ahead should advance at lower levels before the NATO Summit. If these factors can culminate in a symbolic meeting in July in Washington, then a proper presidential bilateral visit could be planned later on, sometime in early 2025.

The current priority for policymakers in Ankara and Washington should be to use every opportunity to preserve momentum. On the U.S. side, Biden should treat a potential NATO Summit meeting as an investment in relations with an important ally and its future, as exemplified in Türkiye’s recent local elections, where the opposition scored a stunning victory. On the Turkish side, Erdoğan’s goal of recovering from a self-inflicted economic crisis is better served by improving relations with the United States and the West in general, where the Turkish economy is overwhelmingly integrated.

Even though these two countries have drifted apart over the years and some aspects of their relationship—such as their respective readings of the global environment—may be less aligned, by and large Türkiye and the United States have a shared interest in maintaining a functioning relationship. In today’s world, the alternative is simply worse, if not riskier, for either side.

Carnegie This Week

Understand the world with the latest from our scholars around the world.

.jpg)

.jpg)