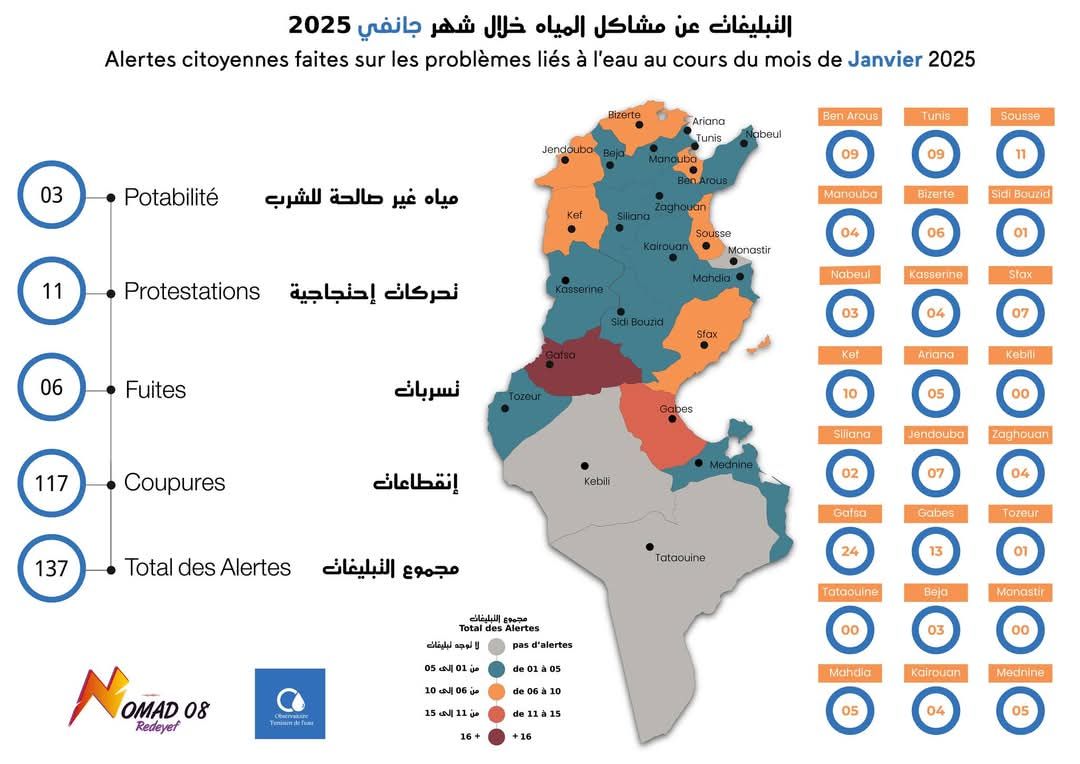

In January 2025, the Tunisian Water Observatory—an independent initiative monitoring water access issues across Tunisia—recorded at least eleven protest movements demanding access to potable water, even though it was the height of the rainy season. These demonstrations, now a near-daily occurrence in both urban and rural areas, underscore a deepening crisis. Across Tunisia, entire communities grapple with securing a resource essential to survival. The situation is particularly dire in rural regions, where potable water supply networks remain underdeveloped, especially in the northwestern and central governorates. Experts attribute the worsening crisis to successive years of drought linked to climate change, compounded by an absence of coherent state policies to mitigate the repercussions. Additionally, Tunisia’s agricultural economy continues to deplete national water reserves, with agricultural policies remaining largely unchanged for decades.

This article critically examines policy measures that can uphold Tunisians’ constitutional right to water and explores actionable strategies for sustainable water management. In doing so, it highlights the growing regional disparities in water access, the structural challenges facing Tunisia’s water infrastructure, and potential policy interventions that could promote equitable distribution.

Escalating Scarcity: The Human and Economic Toll

The water crisis in Tunisia is taking a devastating toll on communities around the country, especially in rural areas. In many of these areas, residents must walk long distances—sometimes on foot or with livestock—to reach water sources, often queuing for hours at public faucets or natural springs. Organizations advocating for water rights have documented numerous testimonies from rural communities struggling to access water. A case in point is the testimony recorded by the Tunisian Water Observatory in the northern city of Tabarka. A local resident described waiting in line as early as 3:00 AM to collect a mere 10 liters of water—barely sufficient for two days. Such scenes are emblematic of a broader crisis affecting rural and urban populations alike.

The scarcity of potable water has also exacerbated agricultural decline, threatening food security and driving up prices. Beyond economic consequences, the crisis has profound public health implications. Water shortages expose citizens to an increased risk of waterborne diseases, such as gastrointestinal illnesses, while prolonged dehydration during extreme heat waves raises the incidence of chronic illnesses such as kidney failure.

The Changing Thirst Map: Data-Driven Insights

Since its establishment in 2016, the Tunisian Water Observatory1— a non-governmental organization dedicated to monitoring and documenting the implementation of national and international commitments in the water sector — has systematically tracked disruptions in water access. Its "thirst map," issued monthly, tracks fluctuations in water availability, reporting water cuts, rising protests, and access to non-potable sources. Notably, in 2024, the thirst map underwent a dramatic shift, with regions like Sfax, coastal areas, and Greater Tunis now facing the highest frequency of drinking water shortages. Alaa Marzouki2, coordinator of the Tunisian Water Observatory, confirmed in an interview that this shift has placed significant pressure on these governorates, particularly due to their dependence on northern dam reserves, which have seen a marked decline in water levels as a result of successive dry seasons and insufficient rainfall. The economic hub of Sfax, Tunisia’s second most populous governorate, has emerged as the most water-stressed region, lacking its own potable water resources and facing escalating summer shortages.

Marzouki also asserted that industrial water consumption has further exacerbated the crisis. In Sfax and Gafsa, extensive industrial activity—particularly phosphate processing—has intensified competition for limited resources, pitting economic priorities against the population’s fundamental right to water. The Water Observatory recorded 2,153 unannounced water cuts in 2024 alone, with Sfax registering the highest number (338), followed by Gafsa (276) and Sousse (207). The number of protest movements linked to water scarcity reached 186 in the same period.

Table 1: Water problems notifications recorded in 2024

Source : Tunisian Water Observatory

The table shows the number of reports concerning water issues during the year 2024. The number of reports about potable water reached 112, while protest movements amounted to 186. Leaks reached 242, and interruptions totaled 2,153. The total number of reports reached 2,693.

Systemic Challenges: Climate Change and Unsustainable Economic Policies

Since 2018, Tunisia has experienced an unrelenting succession of dry seasons that have significantly reduced annual rainfall. Climate experts have long warned of the country’s growing vulnerability to extreme weather patterns, yet government responses have remained inadequate. Houcine Rahili3, a water resources expert at the National Water Observatory, stated in an interview that Tunisia’s water crisis began in the early 1990s. At that time, the overexploitation of groundwater reserves pushed the country into water stress. He further explained that by 2014, Tunisia had entered a critical phase, exacerbated by rising temperatures, increased evaporation, and declining precipitation—a trend mirrored across the Mediterranean basin. Rahili highlighted that the rate of dam filling, which stood at approximately 65% in 2019, had sharply declined to 40% in 2020, and since then, has failed to exceed this threshold, marking an unprecedented situation in Tunisia’s history.

The National Court of Audit’s 2019 water sector report revealed that agriculture consumes nearly 80% of Tunisia’s water resources. Rahili argues that longstanding agricultural policies—centered on export-driven citrus and vegetable cultivation—have further depleted national reserves. He calls for reevaluation of these policies, advocating for a shift towards crops that require less water and align with domestic food security needs.

Policy Recommendations: A Path Toward Sustainable Water Management

Experts and policymakers agree that without decisive state intervention, Tunisia’s water crisis will continue to escalate. Rahili proposes three key policy shifts to address the crisis:

-

Reforming Water Storage Strategies

Contrary to conventional wisdom, dams may no longer represent the optimal solution for water storage. With rising temperatures accelerating evaporation, Tunisia loses an estimated 600,000 cubic meters of dam water daily during peak summer months. Instead, Rahili advocates prioritizing groundwater conservation, which currently supplies 65% of Tunisia’s water needs. Unregulated well drilling—particularly in high-risk “red zones”—must be curbed to prevent further depletion. The 2019 National Court of Audit report found that groundwater exploitation has already exceeded sustainable levels, reaching 126% of available reserves when accounting for illegal wells. -

Adapting to Shifting Rainfall Patterns

While rainfall levels improved between September 2024 and February 2025, Tunisia’s precipitation map has undergone a significant transformation. Historically, the highest rainfall volumes were recorded in northern regions. However, recent data indicate that the central and southern regions experienced a 2.5-fold increase in precipitation compared to historical averages. These areas, however, lack sufficient water reservoirs, leading to massive runoff losses. Investing in localized rainwater harvesting infrastructure—particularly in Sfax, Sousse, Monastir, and Mahdia—could mitigate these losses and improve regional water security. -

Reducing Water Losses in Infrastructure

According to Alaa Marzouki, three primary factors contribute to Tunisia’s high water loss rates:- Aging drinking water networks: Poor maintenance results in the loss of approximately 25% of the country’s potable water.

- Inefficient agricultural irrigation systems: Another major source of water loss lies in Saqwa areas—agricultural lands owned by farmers and provided with irrigation infrastructure by the state. These areas, intended to ensure sustainable agricultural production, paradoxically contribute to significant water waste. An estimated 3 to 4 percent of water in these areas is lost daily due to outdated infrastructure. The 2019 Court of Audit report highlights that 61% of irrigation equipment across the 156,000 hectares of Saqwa areas is obsolete, having gone without modernization for over 25 years. Additionally, 612 Saqwa zones have reported frequent breakdowns in irrigation facilities and water channels, causing recurring disruptions in water distribution. The absence of timely maintenance and investment in these networks further exacerbates inefficiencies, undermining efforts to optimize water usage in Tunisia’s agricultural sector. The report also notes that between 2013 and 2019, water losses in the Saqwa areas’ fetching and distribution networks increased by approximately 3.655 million cubic meters, amounting to 43% of the total water supplied and distributed in these zones.

- Deteriorating dam infrastructure: The condition of Tunisia’s dams represents a significant challenge to water security. Although Tunisia has historically been a pioneer in dam construction, with projects such as the Bani Matir Dam (built in 1954) and the Wadi Kabir Dam (constructed in 1928 to supply water to Tunis), the lack of periodic maintenance and technological advancements has led to severe degradation. Sediment accumulation has reduced dam storage capacity by over 15%, rendering some dams partially or entirely non-operational. Furthermore, the reliance on open-air diversion channels to transport dam water from the north to the capital and other governorates exacerbates evaporation losses, leading to significant inefficiencies. In this context, Alaa Marzouki has emphasized the urgent need for direct government intervention to modernize water transfer infrastructure. He advocates for the adoption of advanced water diversion technologies to maximize resource efficiency rather than over-relying on costly alternatives such as seawater desalination, which could further strain Tunisia’s fragile economy.

Managing Water Reserves: Preventing Overexploitation and Long-Term Depletion

The General Directorate of Dams and Major Water Works under the Ministry of Agriculture regularly assesses Tunisia’s water reserves, tracking storage levels in major dams, water inflows, withdrawals, and overall distribution patterns. As of February 13, 2025, national dam reserves stood at 36% capacity, an improvement compared to the previous six years, with projections suggesting they may exceed 40%. However, experts caution that this temporary reprieve may lead to overexploitation, further depleting already strained reserves and risking a return to the critical 19% level recorded during 2021-2022.

Alaa Marzouki underscored the state’s responsibility in regulating water use and making bold decisions, particularly regarding agricultural policies. Without decisive intervention, he warns, mismanagement could exacerbate the crisis.

In response to mounting pressure, the Ministry of Agriculture introduced new water conservation measures in 2023, including a quota system restricting specific uses of potable water distributed by the National Company for Water Exploitation and Distribution4. The policy prohibits the use of drinking water from the national distribution network for agricultural irrigation, the maintenance of green spaces, street cleaning, and vehicle washing. Furthermore, agricultural delegations5 in several governorates have advised farmers to avoid cultivating water-intensive crops—such as seasonal vegetables—during the current growing cycle. Authorities have also intensified monitoring, warning against illegal water extraction, including unauthorized pump installations along riverbanks and other regulatory violations.

Water Strategy 2050: A Comprehensive Reform Plan

Recognizing the escalating challenges posed by climate change and its detrimental impact on food and water security, the Ministry of Agriculture has developed a long-term strategic framework for the water sector, extending to 2050. As part of this effort, the government has initiated the formulation of action plans for 2026-2030, aimed at implementing targeted interventions that enhance water sustainability and resilience. This comprehensive strategy encompasses 43 projects and 1,200 specific measures, each designed to address critical aspects of water management, infrastructure modernization, and resource allocation. The following are examples of the measures the strategy suggests:

- Enhancing surface water resources by filling existing dams and constructing new water collection centers to facilitate better distribution across governorates.

- Strengthening groundwater reserves through the development of 30 underground dams, ensuring more sustainable extraction and conservation of subterranean water resources.

- Expanding desalination infrastructure, with plans to increase the capacity of four seawater desalination plants and establish four groundwater desalination facilities in the southern regions to address regional disparities in water access.

- Rebalancing water allocation, reducing agricultural sector consumption from 80% to 70% while redirecting the remaining 30% toward drinking water, industrial applications, and tourism.

- Upgrading water infrastructure, with the aim of increasing the efficiency of drinking water systems and irrigation networks from 67% to 85% by 2050. This will involve the modernization of approximately 30,000 km of water distribution pipelines, potentially restoring 300 million cubic meters of lost water annually.

This strategy aims to increase water conservation and efficiency, targeting a daily per capita water savings of 115 liters. However, the current annual water availability remains critically low at 420 cubic meters per person, a stark contrast to the 1,000 cubic meters per year benchmark set by the United Nations as the minimum threshold for water sufficiency. This substantial gap underscores the urgent need for comprehensive water management reforms to bridge the disparity and ensure long-term water security for Tunisia’s population.

Article 48 of Tunisia’s 2022 Constitution enshrines the right to safe drinking water as a fundamental entitlement for all citizens. Yet, the social movements demanding the right to water topped the recorded environmental movements in 2024, according to the latest report from the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights. Achieving water security demands a holistic, multi-stakeholder approach that integrates government action, civil society participation, and expert-driven policy solutions to ensure equitable access to this most vital resource. Experts caution that temporary or reactionary policies will not resolve Tunisia’s structural water crisis. Without a fundamental rethinking of national water governance—including sustainable resource allocation, climate adaptation strategies, and enforcement of water conservation measures—Tunisia risks prolonged instability fueled by worsening water scarcity.

Conclusion: A Call for Coordinated Action

The Tunisian water crisis is a complex challenge driven by climate change, mismanaged resources, and outdated policies. While ambitious reforms such as the Water Strategy 2050 signal a step in the right direction, sustainable water security will require bold policy shifts, enforcement mechanisms, and cross-sector collaboration. Without urgent intervention, continued water scarcity will not only threaten economic stability but also intensify social unrest. Addressing Tunisia’s water crisis necessitates a strategic, multi-stakeholder approach—one that prioritizes conservation, efficiency, and equitable resource distribution to uphold the fundamental right to water for all citizens.

Notes

1Tunisian Water Observatory is an associative project that focuses on examining all issues and concerns related to the right to access water in Tunisia.

2Alaa Marzouki, interviewed in Tunis on February 13, 2025.

3Houcine Rahili, interviewed in Tunis on February 11, 2025.

4National Company for Water Exploitation and Distribution is a government agency that oversees the drinking water sector.

5Agricultural delegations are regional organizations of the Ministry of Agriculture that are present in each governorate.