Recent analysis on the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) foreign policy has highlighted Abu Dhabi's new diplomatic engagements towards former rivals such as Turkey, Qatar, and Iran. In the second half of 2021, visits to Ankara, Doha, and Tehran conducted either by Mohammed bin Zayed—UAE’s de facto ruler—, or by his brother and national security advisor, Tahnoun bin Zayed, suggested a shift in Emirati regional diplomacy. But a closer look at Abu Dhabi's security agenda calls for caution. In fact, these engagements pale in comparison with the other pillars of the UAE’s foreign policy, that is, the deepening of its military cooperation with new partners like Israel and traditional ones like the U.S.

On the surface, these meetings appeared to signal a shift from the UAE’s confrontational strategy of the past decade. This shift was soon coined the UAE's "zero-problem" policy (siaasat sifr mashakel). To a certain extent, the narrative serves Abu Dhabi's interests to restore its international reputation tarnished by years of controversial interventions, including the country’s role in Yemen and Libya. It also feeds into the UAE’s public projection of diplomacy and soft power, especially as it assumes its non-permanent seat at the UN Security Council for the 2022-2023 term.

Ironically, the very expression "zero-problem" was a Turkish invention, precisely from Ahmet Davutoglu, when he took reign of Ankara's foreign policy in the late 2000s. Back then, Turkey had signed agreements with Syria and Iran, while relying closely on NATO and the U.S. for security purposes. Davutoglu's project aimed to build "strategic depth" by balancing Turkey's interests between its Western allies and its Eastern partners. It eventually collapsed amid the Arab uprisings in 2011 and the inability of Ankara to sustain a neutral neighborhood policy. Paralleling this today is the Emirates’ “new” diplomacy, also echoing Qatar's policy of regional mediation from the past decade, which ultimately triggered its dispute with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi.

However, the notion that the UAE is changing the very core of its foreign policy is built on a series of flawed assumptions. First of these is the conclusion that this apparent balancing act of Abu Dhabi is driven by the erosion of its two primary partnerships – the U.S. and Saudi Arabia.

Admittedly, there is basis for Abu Dhabi's frustrations with both countries, but analysts tend to overestimate their implications. Emirati officials are mindful of the U.S. desire to disengage from the Middle East and focus on the Indo-Pacific. But they also see a disconnect between the inflammatory rhetoric in Washington and the enduring presence of U.S. troops in the region.

UAE-U.S. relations have in fact suffered from Washington’s discontent towards Abu Dhabi's cooperation with China in sensitive domains—from the selection of Chinese company Huawei to operate 5G networks to the revelation of a Chinese project to construct a military facility next to the Abu Dhabi Port. But it is unlikely that Abu Dhabi considered its rapprochement with China as a substitute for its cooperation with the U.S. This is less a case of rebalancing than of a miscalculation on the part of the Emiratis who now find themselves in the delicate position of scaling back their cooperation with Beijing to reassure the Americans and save face. Therefore, the U.S. will continue to be the UAE’s most important partner.

Likewise, the Emirati alliance with Saudi Arabia may be fragile at the moment but observers tend to exaggerate the tensions between Abu Dhabi and Riyadh, in the same manner that they have exaggerated the extent of the alliance in the first place. Fundamentally, the Saudi-Emirati alliance is a marriage of convenience among two unequal partners—a regional hegemon and a small state—that share some, but not all, common objectives. The Emirati leadership is well aware of the potential fragility of Abu Dhabi’s relationship with Riyadh. This is evident in the alertness of key decision-makers in Abu Dhabi when Emirati citizens were, for a brief period of time in 2009, barred from entering Saudi Arabia as a result of an unresolved border dispute. And this continues today, for while both countries may disagree on several issues, such as their desired end state in the Yemen war, and they may also openly compete in oil and business policies, Abu Dhabi does not see a serious alternative to its close ties with the Kingdom.

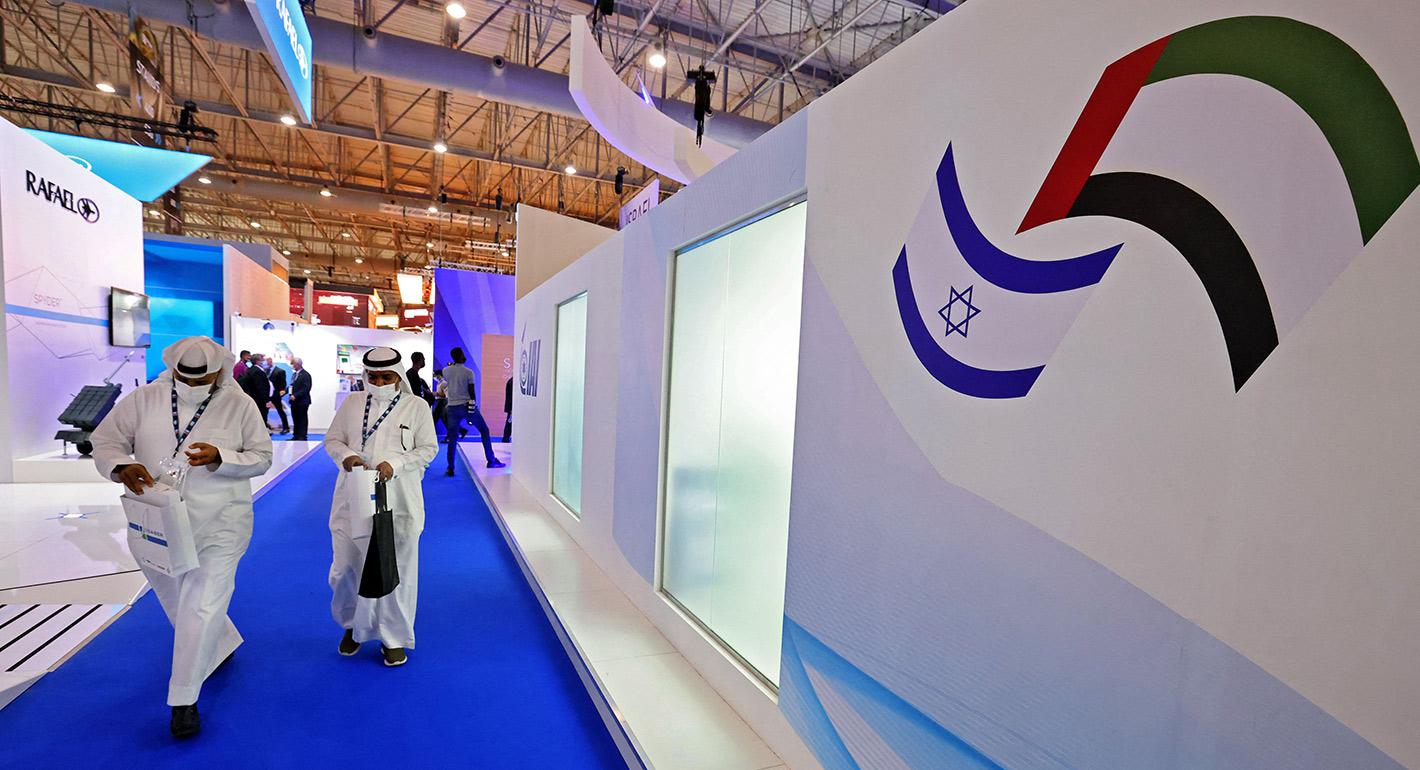

The second flawed assumption is the idea that Abu Dhabi, the "Little Sparta" of the Gulf, is abandoning the employment of its military as an instrument of foreign policy. On one hand, diplomatic engagement with Turkey and Qatar has so far amounted to nothing concrete beyond high-level visits. On the other hand, along with diplomacy, the UAE's new partnership with Israel led to a growing military cooperation between both countries, with intelligence and military officials from both countries meeting with public knowledge of such growing relations.

For instance, Abu Dhabi acknowledged that it was sharing intelligence with the Israelis concerning Hezbollah's capabilities in conducting cyberattacks. Further, just last October, the UAE’s Air Force Chief, Major General Mohammed al-Alawi, made a visit to Israel. A month later, Israeli and Emirati naval forces, for the first time, took part in a joint exercise under the auspices of the U.S. Fifth Fleet. These naval maneuvers, taking place in the Red Sea, evidenced the resolve of Israelis and Emiratis to go beyond the mere diplomatic normalization of their relations. It served as a signal of deterrence to Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps whose ships regularly engage in harassment tactics in the maritime area. Such a message of deterrence is arguably more consequential than Tahnoun's visit to Tehran.

Again, the fact that the naval drill was coordinated by the U.S. Navy reveals how much the U.S. remains a key ally to the UAE and its strategic foreign policy decisions. During that same period, Abu Dhabi also joined the new U.S. initiative of a quadrilateral dialogue involving the UAE, India, Israel, and Washington. Taking place in October, the meeting was hastily nicknamed the "Middle East" QUAD, mirroring a similar U.S.-led initiative in the Indo-Pacific. A second meeting is now scheduled for March 2022. Though the security implications of this new alliance remain yet to be seen, taking part in this it is yet more evidence of Abu Dhabi’s intention to anchor its security policy to Washington’s interests.

Therefore, the extent of a shift in UAE regional policy and its supposed embrace of a new zero-problem approach should not be inflated. Regional instability may have eased but only temporarily. High-level visits have, to some extent, alleviated regional tensions, especially in countries where politics remain highly personalized. But they did not materialize in any concrete new mechanisms to settle pre-existing disputes. Information warfare between Doha and Abu Dhabi did not disappear either: Qataris and Emiratis continue to confront each other through their own state and non-state media, illustrated in the continuing ban of Qatar’s Al Jazeera in the UAE.

Meanwhile, engaging with Tehran did not prevent Abu Dhabi from strengthening its deterrence capabilities, be it through its naval maneuvers with Israel or the upgrading of its air force, as shown most recently with the purchase of 80 new Rafale fighter jets. Suspicions over the possible involvement of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in the recent wave of drone and missile attacks on Abu Dhabi from Yemen could derail the process of confidence-building between the UAE and Iran.

All in all, the study of Abu Dhabi's regional policies highlights the false notions of a major Emirati shift towards accommodation and conflict resolution. After all, the UAE continues to believe in the primacy of coercive means to support its foreign policy ends.

Jean-Loup Samaan is a senior research fellow at the Middle East Institute of the National University of Singapore as well as an associate fellow with the French Institute for International Relations (IFRI). Follow him on Twitter: @JeanLoupSamaan.