Volodymyr Zelensky’s five-year presidential term expires on May 20, 2024. When he was inaugurated, Zelensky promised to bring peace to Ukraine, to root out the corrupt elite, and to serve just one term as president. But time is a cruel and fickle master. Now Ukraine is embroiled in a full-scale war as it defends itself against Russian aggression; domestic politics is plagued by corruption; and Zelensky stands accused of seeking to usurp power. As it’s impossible to hold elections while martial law is in place, Zelensky will remain in power after his term expires. This creates an unexpected problem for Ukrainian democracy.

The doubts about Zelensky remaining in his post after May 20 arise from the vagueness of Ukrainian law. While the constitution does not explicitly ban holding presidential elections under martial law, it also states that the president should continue to serve until a successor is elected (Article 108), and that presidential terms last five years (Article 103).

Ukrainian lawyers point out that the absence of a mechanism for extending a president’s term is a deliberate omission—so as to reduce the risk of abuse of power. At the same time, Ukrainian electoral law forbids the holding of elections during martial law.

Officials maintain that after May 20, Zelensky will become acting president until the next election. However, his opponents interpret the law in such a way as to argue it’s the speaker of the Ukrainian parliament who should become acting president: that’s who the constitution deems to be the next in line if the president is no longer able to fulfill his duties.

There is a precedent in recent Ukrainian history for a parliamentary speaker becoming acting president. That’s what happened in 2014, when President Viktor Yanukovych fled the country amid a popular uprising in Kyiv. After Yanukovych’s abrupt departure, Speaker Oleksandr Turchynov became acting president. He then handed power to Petro Poroshenko, winner of the subsequent presidential election.

Unsurprisingly, Zelensky is not a fan of this option. And Ruslan Stefanchuk, the current parliamentary speaker and a member of the pro-Zelensky Servant of the People party, is not seeking the presidency. He has already publicly confirmed that Zelensky will be acting president until elections take place.

However, parliament is no longer as unquestionably accepting of Zelensky as it once was. Davyd Arakhamia, the head of the Servant of the People faction in parliament, is on record stating that the political consensus that existed at the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion has collapsed. And that means there could be a different speaker in parliament: one who might push to be made acting president. Given the deepening divisions in Servant of the People, Zelensky’s opponents may try to restructure the parliamentary majority after May 20 in an attempt to force the president to hand power to a new speaker.

Ukraine’s Constitutional Court could resolve this dispute, but Zelensky’s office is unwilling to involve it. Firstly, such a move could be interpreted as proof that there are doubts even among Zelensky’s team about his legitimacy. Secondly, Zelensky is locked in a long-running dispute with Constitutional Court judges over their resistance to anti-corruption legislation. The court could well, therefore, issue a ruling that would only complicate the situation further.

Of course, on their own, the accusations of illegitimacy against Zelensky are unlikely to bother ordinary Ukrainians, but if they are accompanied by significant military and social problems, then they could become more serious.

For the moment, public opinion is on Zelensky’s side. According to a February poll by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, 69 percent of Ukrainians want Zelensky to continue as president until martial law is lifted, and 15 percent want him to stay on until new elections. Just 10 percent want to see the parliamentary speaker become acting president. As many as 53 percent would like to see Zelensky stand for a second term, though that figure is gradually declining.

For Zelensky’s main opponent, former president Poroshenko, the legitimacy issue is a useful way of exerting pressure—with the aim of forcing the government to share power in a broader coalition. Some of Zelensky’s former allies are also speaking out over the issue. Ex-parliamentary speaker Dmytro Razumkov believes that the president’s term ends on May 20 and he should cede power to the speaker. Formerly influential Servant of the People parliamentary deputy Oleksandr Dubinsky (currently under investigation on treason charges) has directly accused Zelensky of usurping power.

Of course, Kremlin propagandists will do their best to amplify questions about Zelensky’s legitimacy. The narrative is an obvious one: Russian President Vladimir Putin was elected for a fifth term in Russia’s March presidential vote, while Zelensky canceled Ukraine’s elections. The fact that Russian elections are a sham is a minor detail in such narratives.

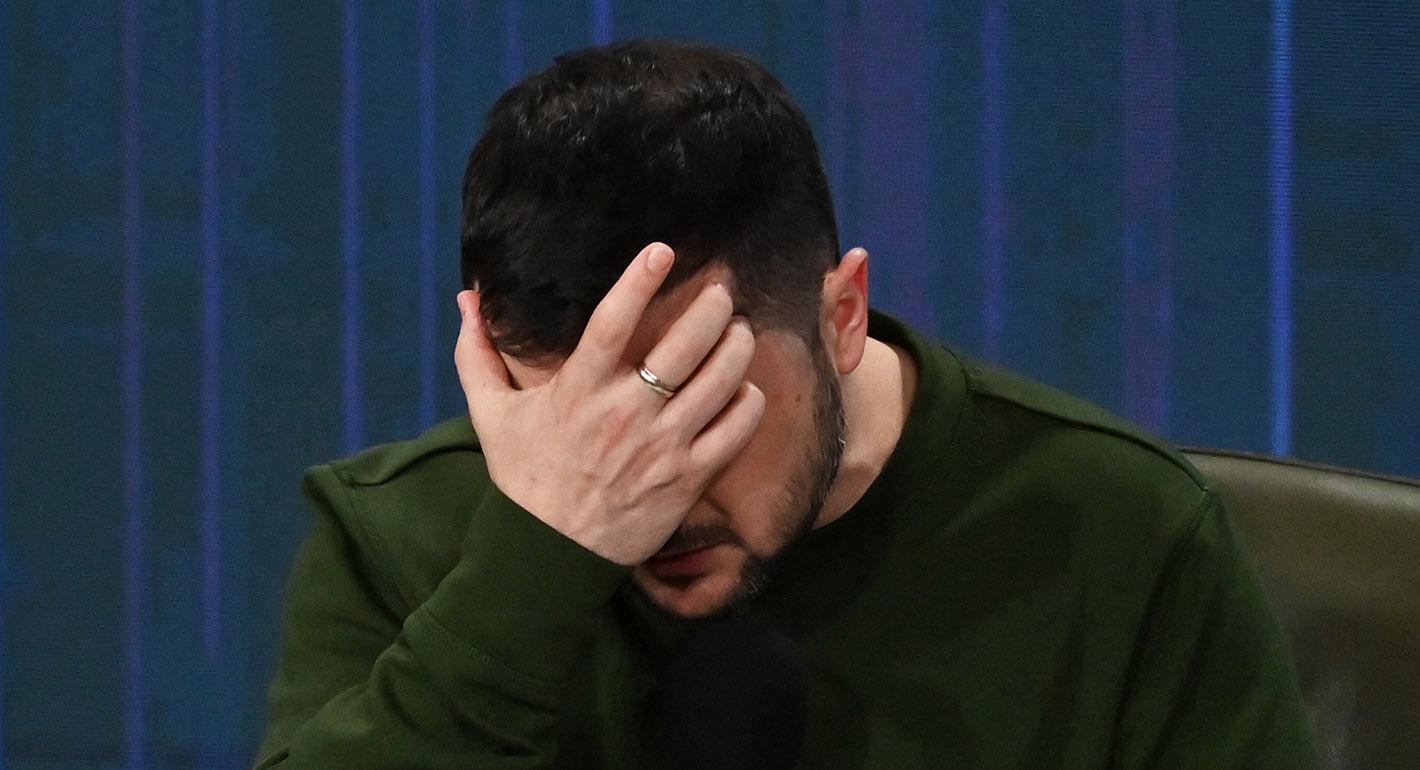

The main problem is that Zelensky is becoming nervous and starting to overreact to allegations of illegitimacy. Since the firing of General Valery Zaluzhny, Ukraine’s top military commander, which shook public trust in Zelensky, the president has begun to use cliched and unconvincing rhetoric about unspecified attempts to “rock the boat.” He has warned about the risks of some sort of uprising, and hinted that any attempts to question his legitimacy will be seen as part of an enemy plot to destabilize the country. Officials are even discussing a response that could include shutting down the popular messaging app Telegram.

It’s inevitable that the Kremlin will seek to promote any suggestion that the Ukrainian government is illegitimate—that’s been a staple of Russian propaganda for a decade. Putin has long referred to the 2014 revolution in Ukraine as a “coup.” For this reason, Zelensky’s statements about pro-Kremlin conspiracies will likely be seen by most Ukrainians as an attempt to intimidate his opponents. In other words, they could backfire.

The situation is full of grim irony. Regular power transitions were one of the achievements of Ukrainian democracy, setting it apart from most other post-Soviet countries, particularly Russia and Belarus. It’s unsurprising that even the slightest threat to this achievement is enough to send shockwaves through both Ukrainian society and its political elite.