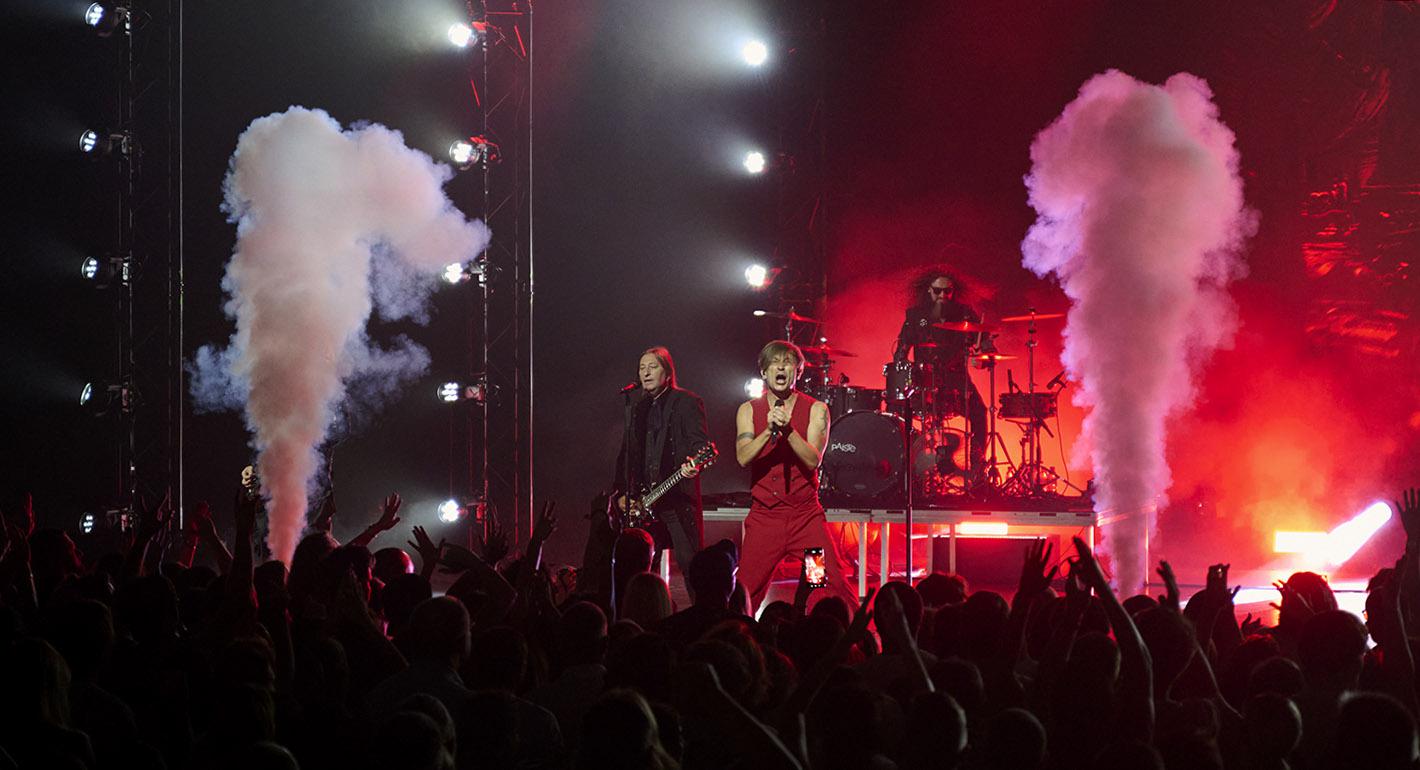

Russia’s latest special operation—last week’s failed attempt to deport members of the veteran rock band Bi-2 from Thailand to Russia, where they could have faced charges over their anti-war stance—was thwarted when it went from being a police matter to a political issue. The episode is indicative of the Russian regime’s crackdown on political emigres, and, most importantly, of the Kremlin’s relationship with the non-Western world.

Moscow has been at great pains to present supposed solidarity with the non-Western world as part of its attempts to get the Global South on side in Russia’s war against Ukraine, but in springing this particular operation on Thai territory, it has misled and embarrassed the Thai government and shown contempt for the Asian country’s own interests.

It is often said now that Russia is at war with a version of the West that exists only in Moscow’s imagination. It seems that Russian ideologues’ image of an East and South that are allied to Russia—or even simply neutral—are no less fantastical.

The official reason for Bi-2’s problems after performing on the popular Thai island of Phuket was that the group had traveled there on the wrong kind of visa: a formality apparently often ignored or swiftly resolved. The group was reportedly arrested at the request of the Russian consul in Phuket. Like its neighbors, Thailand has not sanctioned Russia and is not helping Ukraine. Russians can still fly there and indeed continue to do so in vast numbers. Accordingly, Thai police are used to working with Russian consuls to solve the numerous headaches caused by or encountered by Russian tourists. Their instinctive reaction when approached by the consul about musicians who had broken laws in both Thailand and Russia, therefore, was likely receptive. Russian authorities, meanwhile, were likely counting on being able to get the rockers onto the first plane to Russia—where they would likely have faced charges of “discrediting” the Russian army over their opposition to the war in Ukraine—before it had chance to become a political issue.

That plan failed when Israeli, Australian, and other Western diplomats got involved, since some of the band members have dual nationality. The musicians were transported to Bangkok, the Thai national government became involved, and eventually all the musicians were permitted to leave for Israel. The outcome showed that the Global South may not have thrown its conditional support behind Ukraine, but nor is it Russia’s unquestioning ally—especially where Moscow’s domestic foes are concerned.

Indeed, it's unclear why Moscow ever believed that the government of Thailand, a traditional U.S. ally, would deport people facing political persecution back to Russia. It was Thailand, after all, that extradited the notorious Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout to America in 2009 over Moscow’s protests.

If anything, Russia's cack-handed attempt at revenge may have the opposite effect to that intended. Now the Thai authorities will think twice before actioning a request from the Russian consulate, wary of the prospect of political consequences. Indeed, thanks to the attention this incident has attracted, any deportation to Russia will now be seen as a political problem, even in countries far removed from the war in Ukraine.

This is particularly important at a time when the Kremlin’s stance on the newest wave of political immigration is changing. Until recently, the Kremlin seemed glad that critics of the war and the regime had left the country. There was even an internal discussion about whether some of them could be allowed back. Now Moscow seems keen to show that, just as in Soviet times, it has a long arm.

The regime is strangling its enemies by making sure they cannot receive income from sales of tickets or their work, and even from selling or renting out property that belongs to them. The attempted deportation coincided with several famous emigre Russian writers being declared terrorists and extremists for having voiced support for Ukraine. That means dissident authors will no longer receive any income from the sale of their books in Russia. In another development last week, the Russian parliament passed an unconstitutional law enabling the state to confiscate the assets—including property—of Russians found to have “discredited” the Russian army or called for sanctions against Russia.

In undertaking these endeavors, the Russian authorities are counting on the cooperation—or at the very least, solidarity—of non-Western countries. But as usual, they are seriously overestimating the desire of those countries to side with Russia against the West, especially against Moscow’s domestic enemies. The truth is that Russia, with its obsession with “traditional values” and “LGBT propaganda,” has a lot less in common with countries in the Global South and East than it believes.

It’s hard to imagine countries like Brazil, Mexico, or South Africa, which have legalized gay marriage, extraditing LGBT activists at Russia’s request. India, with its own dynamic political scene, is unlikely to have any sympathy for Russian laws annihilating freedom of speech. Despite the legacy of the Cold War-era friendship between India and Russia and a booming oil trade between the two countries, India is bolstering its relations with the West and diversifying its arms supplies. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa appears to have persuaded his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin not to attend the BRICS summit there to avoid casting doubt on the independence of the country’s legal system, since South Africa is signed up to the International Criminal Court, which has charged Putin with war crimes. And at the same time as the Bi-2 saga was unfolding in Thailand, Rome was hosting an Italy-Africa summit that was attended by more African leaders than Russia’s own such event.

Instead of becoming more closely aligned, as Moscow intended, the agendas of Russia and the Global South are only drifting further apart. This is a direct result of Russia’s attempts to drag its partners into its own battle against both its domestic enemies and against the West in order to spread the responsibility for its own political madness.

But in the real world, rather than the imaginary developing world, there is far less appetite to step into this role than Moscow believes. Other countries may use Russia’s temporary insanity to further their own interests, but that’s where it ends.