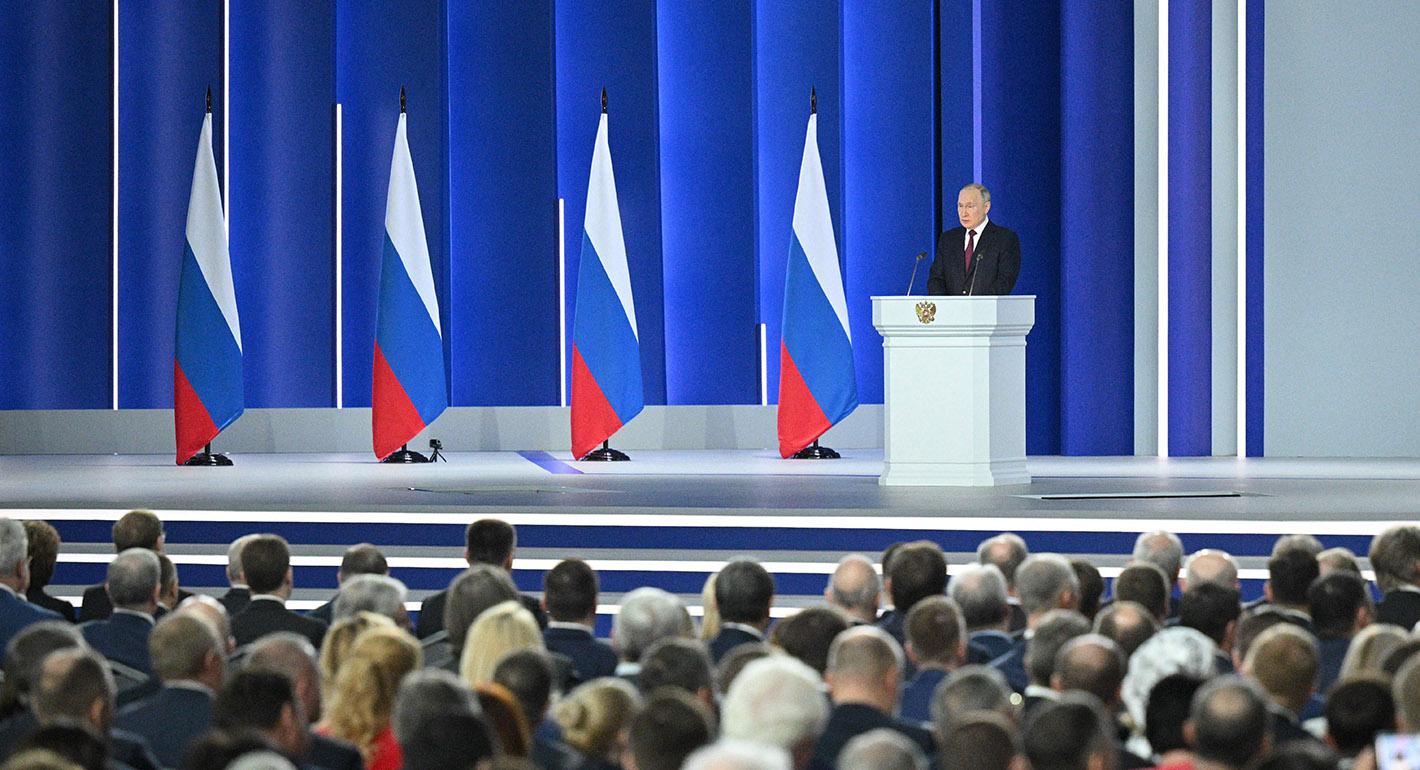

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s state of the nation address on February 21 was eagerly anticipated inside Russia. Yet it shed no light on the question that is foremost on the minds of the Russian elite and public: how Putin intends to win this war.

The address had been postponed from last year, prompting speculation that Putin didn’t know what to say amid the lack of victories at the front. It’s more likely, however, that he was just too immersed in his unsuccessful military campaign to find the time. In the end, the address was a mixture of what Putin considered it necessary to say (the geopolitical part about the “crazy” West), and what he is required to say under the constitution (an update on Russia’s socioeconomic situation).

Putin did say that all upcoming elections, including the presidential election in March 2024, would be held as planned, which should put an end to speculation that they might be canceled or postponed. Once again, the president demonstrated a complete lack of concern that the system he has built could be anything other than strong and stable, despite sanctions and the war. Putin clearly continues to believe that he has broad support among both the public and the elites.

The result was a somewhat imbalanced speech. Putin spent half an hour discussing the West’s intentions to subjugate Russia, and then another hour talking about day-to-day socioeconomic problems in a tone of optimism, as if nothing in particular was happening.

Given all the buildup about the “crazy” West, what was clearly missing was an outline of measures to be taken in response. It’s becoming increasingly difficult for Putin to combine his rhetoric of alarm and escalation regarding the West with his optimism on domestic affairs and his eternal silence on what comes next.

In the first part of the address, Putin spoke in more emotional and radical terms than usual about the destructive role of the West, appearing increasingly convinced that the West is intent on inflicting a “strategic defeat” on Russia at any cost. A year ago, he expected the West to be more passive in its support for Ukraine. Now the war with Ukraine is, in Putin’s eyes, becoming just a minor episode in the West’s global war against Russia: a war of civilizations aimed more or less at the physical destruction of the Russian world.

Perceived as a threat to Russia’s very existence, the West has stopped being a potential interlocutor for the Russian president, and has turned into a strategic aggressor, planning to—in Putin’s words—“finish us once and for all.” Putin hasn’t yet said so outright, but his address implies that Russia and the West are incompatible, so Russia can do nothing but fight to be the last one standing in the battle for survival.

The main message that Putin wanted to get across to the West in his speech was that “it is impossible to defeat Russia on the battlefield.” He was essentially warning that the intention to defeat Russia will make the war a long one, and will bring about the large-scale destabilization of the entire world, but will never end in victory over Russia.

Having lost any hope of dealing with the “traditional” West, now considered a military adversary, Putin continues to address the “right West”: in Putin’s eyes, pragmatic elites focused on the national interest, and ordinary people who would like to restore normal relations with Russia.

He also appealed to countries that have not sanctioned Russia, presenting the West as a threat to their sovereignty, stability, and economic prosperity. This was an attempt to fan the flames of anti-Western sentiment in the non-Western world, and erode the support of the traditional elites in Western countries by showing that any mission to inflict a “strategic defeat” on Russia will take its toll on the whole world.

Putin waited until the end of his address to drop in the biggest piece of news: that Russia would suspend its participation in the New START nuclear arms reduction treaty with the United States. This was a predictable decision, as Russia had since August denied access to U.S. inspectors and stymied a meeting of the treaty’s bilateral consultative commission.

Putin is presenting something of an ultimatum: either the West drops its anti-Russia policy, or the world will face creeping multifarious nuclear escalation. Putin used his speech to say that the Defense Ministry and Rosatom, the state nuclear energy corporation, must be ready to test nuclear weapons in response to any tests undertaken by the United States. Russia could also formally withdraw from the New START, which would be seen as a more radical measure.

It’s extremely unlikely that Moscow’s goal is really the revision of the New START, just as Putin’s deliberate mention of Britain and France as directing their own nuclear arsenals against Russia is anything but a call for those countries to enter in a dialogue with Moscow. More likely, it’s an attempt to demonstrate that Moscow is ready to dismantle all of the treaties and formats for dialogue until the West reconsiders its policy with regard to Russia. It’s a move to put an end to the previous system of communication with the West, with very little room for unofficial channels.

Putin’s state of the nation address effectively suggests that in the growing confrontation with the West, Russia will rely on one sole argument: the nuclear option. In this respect, suspending the New START treaty also sends a warning to non-Western countries of the consequences for the entire world of the West’s anti-Russian policies. Moscow is presenting the global community with a choice between Russia or descending into a nuclear disaster.

For Putin, the concept of victory has meaning far beyond the borders of Ukraine: it would mean nothing less than an end to the West’s anti-Russian policies. It’s true that this vision differs dramatically from the expectations of the Russian elite and public, who would prefer to have a bird in the hand (the Donbas) than two in the bush (an end to the West’s anti-Russian policies). The practical reality of the conflict with Ukraine has less and less in common with Putin’s stratospheric expectations, and this discrepancy could well become a factor in bringing about political change within Russia itself.