Summary

The year 2024 was widely hailed as the “year of elections.” Over twelve months, more than 1.5 billion people exercised their franchise to select new governments in seventy-three countries across the globe. Two of the biggest—and, arguably, most consequential—elections occurred in India and the United States.

In June 2024, voters in India delivered a third term to incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi, despite his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) falling short of an outright parliamentary majority. While Modi remains a popular, domineering figure, the results of the general election were widely perceived as a political setback. However, with resounding victories in several subsequent state elections, Modi and the BJP appear to have recovered some lost ground. Five months later, voters in the United States once again reposed their trust in Republican President Donald Trump, denying then vice president Kamala Harris an opportunity to succeed Democratic incumbent Joe Biden.

These two noteworthy elections took place against the backdrop of a burgeoning U.S.-India partnership, albeit one not without its hiccups. In the run-up to the U.S. election, several irritants to the bilateral relationship emerged, including disagreements over the approach toward the Sheikh Hasina–led regime in Bangladesh, the U.S. federal indictment of Indian billionaire Gautam Adani on corruption charges, and a dispute over allegations that an Indian government official masterminded a “murder-for-hire” plot targeting a U.S. citizen—a pro-Khalistan separatist—on U.S. soil.

Given that more than 5 million people of Indian origin reside in the United States today, these developments naturally invite questions about the diaspora’s views on foreign policy: How do Indian Americans evaluate the Biden administration’s stewardship of U.S.-India ties? Do they think Trump will be better for India? How do they view India’s own trajectory, including the results of the June 2024 election?

This study seeks to answer these timely, important questions. The analysis is based on a nationally representative online survey of 1,206 Indian American adult residents—the Indian American Attitudes Survey (IAAS)—conducted by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace between September 18 and October 15, 2024, in partnership with the research and analytics firm YouGov. The survey has an overall maximum margin of error of +/- 3 percent.

In brief, the data reveal that Indian Americans believe the recently departed Biden administration ably managed U.S.-India ties during its four years in office. However, they offer a more mixed assessment of what future relations under Trump might entail. With regards to India, the diaspora is more bullish on the country’s domestic trajectory compared to 2020. A near majority of Indian Americans approve of Modi’s performance as prime minister, though many are concerned about rising Hindu majoritarianism.

This study is the second in a three-part series on the social, political, and foreign policy attitudes of Indian Americans drawing on the 2024 IAAS. The major findings are summarized below:

- Indian Americans view the Biden administration’s record on India positively. More than two-thirds of respondents approve of the Biden administration’s handling of U.S.-India relations. Roughly four in ten believe the administration’s support for India was appropriately calibrated, though there are diverse opinions on how well the United States balanced its interests versus its values.

- Many Indian Americans are concerned about bilateral relations under the Trump administration. Indian Americans rate the Biden administration’s record on India slightly better than the first Trump administration’s. In addition, respondents believe the bilateral relationship would have been more likely to prosper under a putative Harris administration compared to a second Trump administration.

- The “murder-for-hire” allegations, while sensational, are not well known. Only about half of all respondents are aware of the allegations of India’s involvement in an attempted assassination on U.S. soil. A slim majority of respondents report that India would not be justified in taking such action and hold identical feelings about the United States if the positions were reversed.

- Indian Americans are divided on the question of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Indian Americans do not hold a monolithic view of the conflict in the Middle East, though there are clear partisan divides. Democrats are more likely to side with and express empathy for the Palestinian cause than Republicans, who espouse more pro-Israel views. Overall, four in ten respondents state that the Biden administration favored Israel too much in the ongoing conflict.

- Compared to 2020, Indian Americans are more bullish on India’s trajectory. Forty-seven percent of Indian Americans believe that India is headed in the right direction, a 10 percentage point increase from four years ago. The same share approves of Modi’s prime ministerial performance. Four in ten respondents report that India’s 2024 election made the country more democratic.

Introduction

When it comes to voters exercising their franchise at the ballot box, there is no doubt that 2024 was a banner year. With the benefit of hindsight, it was not simply a year of critical elections but also one with a distinct, anti-incumbent tenor. According to the Financial Times, “the incumbent in every one of the 12 developed western countries that held national elections in 2024 lost vote share at the polls, the first time this has ever happened in almost 120 years of modern democracy.” The November U.S. election fits this pattern perfectly, with challenger and former president Donald Trump returning to power and Democratic candidate and sitting vice president Kamala Harris losing.

The developing world was not completely immune from the anti-incumbent backlash. In India, which held the world’s largest election in recorded history, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of Prime Minister Narendra Modi returned to power for a third consecutive term, albeit in a much weaker position than in the previous two elections. In contrast to the parliamentary majorities the BJP obtained in 2014 and 2019, the ruling party won 240 seats in 2024, comfortably making it the single largest party in the Lok Sabha but short of the 272 seats needed to form the government without the help of coalition allies.

These two developments took place against a backdrop of growing ties between the United States and India. The countries have built increasingly stronger linkages in areas including national security, energy cooperation, intelligence-sharing, and education over the past four years.

Yet U.S.-India bilateral ties have encountered their fair share of turbulence of late. The current Indian government often chafed at Biden administration officials’ comments on democracy and human rights conditions in India, claiming they are “internal” issues. The U.S. Justice Department, for its part, is pursuing two high-profile legal cases that irk many in the Indian government. In October, it announced charges against an Indian government employee in connection with an alleged plot to kill a U.S. citizen, whom the Indian government claim is a terrorist advocating for an independent Khalistan (a homeland for the Sikh population). The next month, the department indicted billionaire industrialist Gautam Adani on charges of corruption and fraud.

These incidents and other geopolitical tensions have tested the mettle of the U.S.-India relationship while raising questions about how Indians in America view the relationship, developments in their country of origin, and the foreign policy landscape more generally. An earlier study by the authors, published in October 2024, detected important shifts in the diaspora’s attitudes and preferences regarding U.S. politics. Most notably, there was a clear erosion in the extent of Indian American support for the Democratic Party, which it had historically supported by a 70–20 margin. In 2024, that gap shrunk to 60–30 and even more among certain demographic groups, such as young men. This shift telegraphed the outcome of the presidential election and begs the question of whether similar changes are afoot when it comes to the foreign policy domain.

To examine this question, this study trains its attention on the foreign policy views of Indian Americans. Its findings are based on a nationally representative online survey of 1,206 Indian American residents in the United States—the 2024 Indian American Attitudes Survey (IAAS)—conducted by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace between September 18 and October 15, 2024, in partnership with YouGov. The survey, drawing on both citizens and noncitizens in the United States, was conducted online using YouGov’s proprietary panel of U.S.-based participants and has an overall maximum margin of error of +/- 3 percent.

Findings from the 2024 survey build on the 2020 IAAS, a similar survey fielded by the authors ahead of the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Both the 2020 and 2024 iterations are cross-sectional surveys of the Indian American population. The IAAS is not a panel dataset that interviews the same respondents over time. Therefore, one must exercise caution in using the two surveys to interpret changes in the Indian American population over time.

This study addresses five questions concerning Indian Americans’ views of U.S.-India ties, domestic developments in India, and the conduct of U.S. foreign policy:

- How do Indian Americans evaluate the Biden administration’s handling of the U.S.-India relationship?

- What are the prospects for U.S.-India ties, and how do diaspora members view recent controversies such as the “murder-for-hire” allegations?

- How do Indian Americans view the Israel-Hamas war and the Biden administration’s response?

- How do Indian Americans assess India’s trajectory, including the state of Indian democracy?

- How do Indian Americans evaluate the performance of leading parties and political figures in India?

This study is the second in a series of empirical reports on Indian Americans’ views during the 2024 U.S. election cycle. The first, released in October 2024, explored the political attitudes and preferences of Indian Americans in advance of the November presidential election. The third and final study will explore the social realities of Indians in America.

- Sumitra Badrinathan,

- Devesh Kapur,

- Milan Vaishnav

Survey Overview

The data for this study are based on an original representative online survey—the 2024 Indian American Attitudes Survey—of 1,206 Indian American adults. The survey was conducted by polling firm YouGov between September 18 and October 15, 2024. The survey included both U.S. citizen and noncitizen respondents.

YouGov recruited respondents from its proprietary panel of 500,000 active U.S.-based residents. For the 2024 IAAS, only adult respondents (ages eighteen and above) who identify as Indian American or a person of (Asian) Indian origin could participate. YouGov employs a sophisticated sample matching procedure to ensure that the respondent pool is representative of the Indian American community in the United States. All the analyses in this study employ sampling weights to ensure representativeness.1

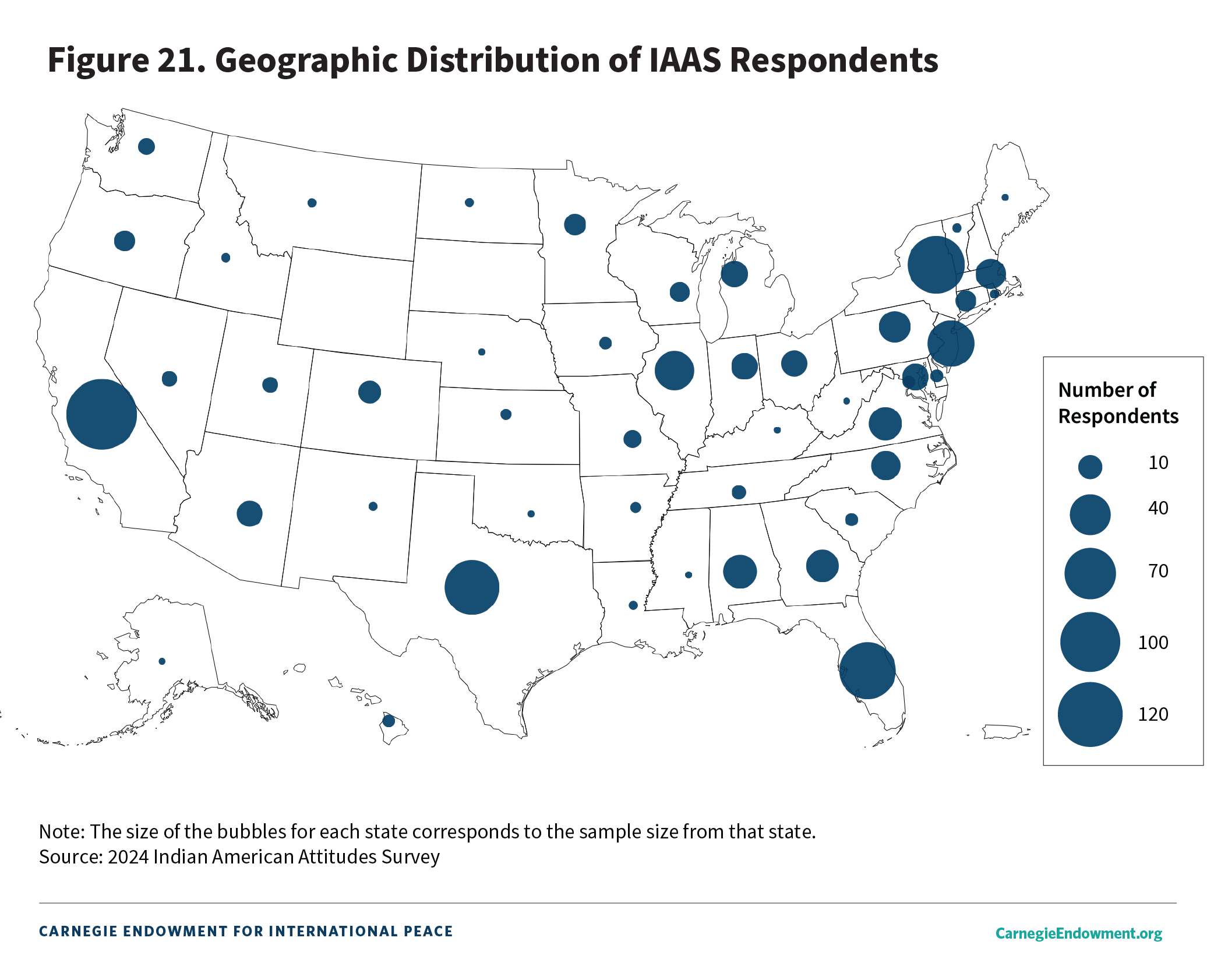

The overall maximum margin of error for the IAAS sample is +/- 3 percent. This margin of error is calculated at the 95 percent confidence interval. Further methodological details can be found in appendix A, along with a state-wise map of survey respondents.

The survey instrument contains over one hundred questions organized across five modules: basic demographics; U.S. politics and voting behavior; foreign policy and U.S.-India relations; culture and social behavior; and Indian politics. Respondents were allowed to skip questions except for certain demographic questions that determined the flow of other survey items.

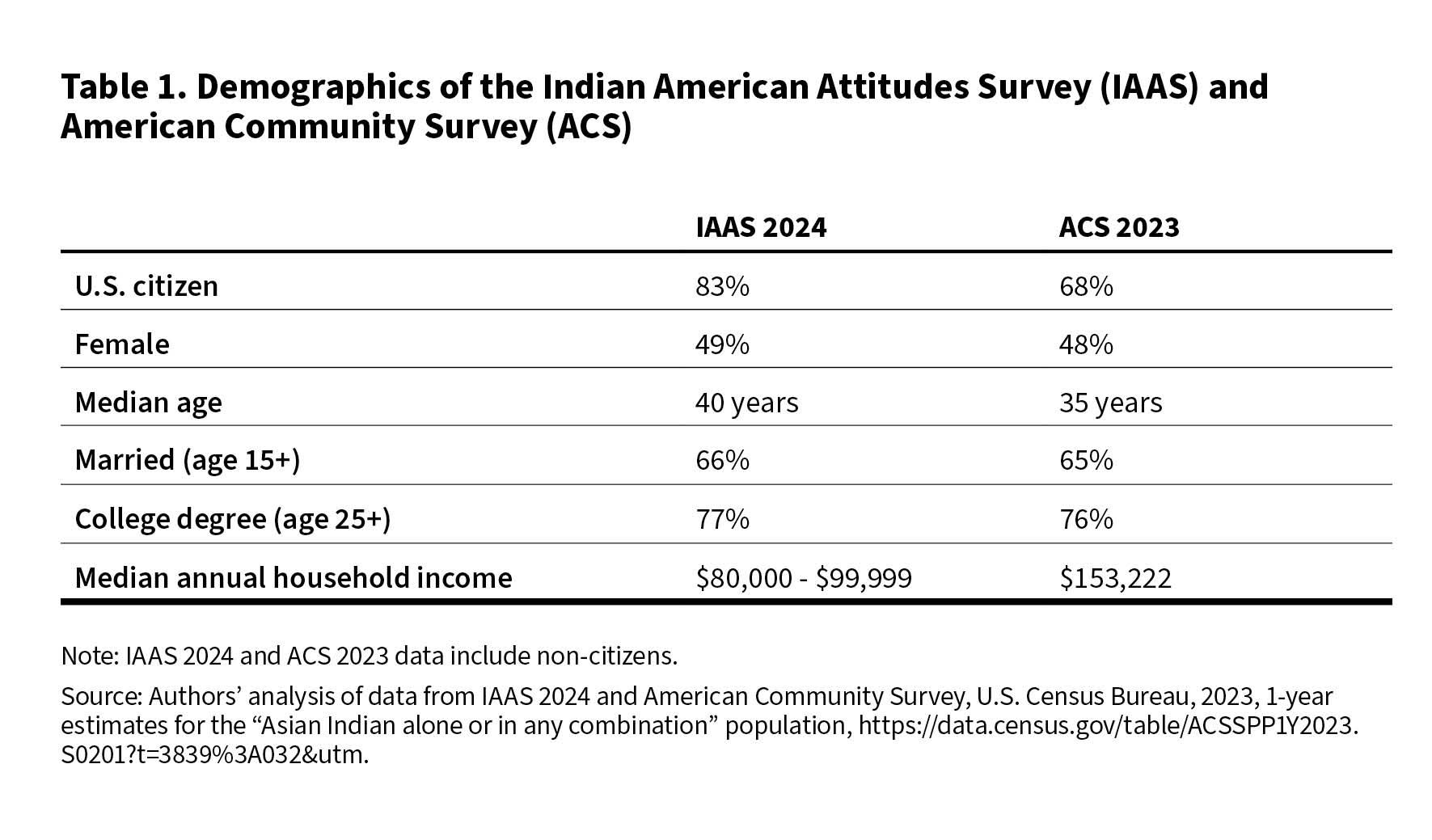

Table 1 provides a demographic profile of the IAAS sample in comparison to the Indian American population as a whole. The latter relies on data from the 2023 American Community Survey (ACS) on the Asian Indian population in the United States.2 The ACS is an annual demographic survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau and is widely used to construct sample survey frames in the United States.

The Biden Administration’s Record on U.S.-India Relations

Overall, survey respondents espouse a favorable view of the Biden administration’s approach toward India over the past four years (see figure 1). Thirty-one percent of respondents strongly approve of the administration’s handling of U.S.-India relations while another 17 percent approve—48 percent are favorably disposed in the aggregate. A combined 23 percent of respondents either disapprove or strongly disapprove of the Biden administration’s stewardship of the bilateral relationship. Respondents demonstrate a more positive assessment of Biden’s handling of U.S.-India ties compared to their evaluation of Trump’s record in 2020. Data from the 2020 IAAS reveal that only 33 percent of respondents approved of Trump’s handling of bilateral ties at the end of his first term.

The survey proceeds to ask respondents to evaluate the extent of U.S. support for India in the twilight of the Biden administration’s four-year term in office (see figure 2). Thirty-eight percent of respondents, a plurality, report that U.S. support for India is at an appropriate level. However, 28 percent view the United States as insufficiently supportive of India, while 17 percent hold that the United States is too supportive of India. Sixteen percent of respondents express no opinion either way.3

When examining differences by place of birth, respondents born in the United States are more than twice as likely to say that the United States is too supportive when compared to respondents born abroad (27 percent versus 11 percent). The other discrepancy relates to the share of respondents who do not express an opinion, with one in five immigrants choosing this option compared to one in ten U.S.-born respondents.

One of the critical debates coloring the popular discourse on U.S.-India relations over the past four years, and arguably for the past decade or more, is whether Washington should prioritize democratic values or its broader strategic interests when it comes to structuring its relationship with New Delhi. The survey asks respondents to provide their assessment of the relative weight the Biden administration placed on democratic values as compared to larger geopolitical or strategic interests (see figure 3). Although the data are suggestive of respondents’ own preferred trade-offs, the question narrowly asks about their assessment of the Biden administration’s policies.

Interestingly, there is very little consensus on this question. A plurality of respondents (31 percent) report that the Biden administration struck the right balance between promoting democratic values and protecting America’s long-term strategic interests. Twenty-eight percent report that the U.S. administration prioritized its long-term strategic interests over its concerns about India’s democracy. Only 17 percent state that the United States prioritized its concerns about India’s democracy over its long-term strategic interests. Nearly one-quarter (24 percent) do not report a clear view.

The distribution of responses is noteworthy because Indian Americans are seen as broadly supportive of Modi and one might expect that many diaspora members might recoil at U.S. criticism of India’s democratic trajectory. Indeed, some critics argued that the Biden administration allowed its concerns with “values” to trump the country’s larger strategic “interests.” These critics pointed to the U.S. Department of Justice’s indictment linking an Indian government official to an alleged plot to kill a pro-Khalistan activist on U.S. soil and the Biden administration’s criticism of Bangladeshi prime minister Sheikh Hasina, a stalwart ally of India who was ousted from office in August 2024.

Notably, there is little partisan variation on this question. There are virtually no differences in the distribution of responses based on respondents’ ties to either major U.S. political party.

Finally, the survey probes respondents’ views of the two most recent U.S. presidents’ relative performances. The survey asks which president did a better job managing U.S.-India ties (see figure 4). Thirty-four percent of respondents identify Biden as doing a better job, and 28 percent report Trump handled bilateral relations better during his first term. Roughly the same proportion, 26 percent, feel the presidents’ performances were generally the same. An additional 12 percent report that they do not know.

The small difference in the aggregate between the two presidents conceals the dramatic variation by respondents’ partisan affiliations, reflecting the overall degree of partisan polarization in the United States (see figure 5).4 Sixty-six percent of Republican respondents believe Trump was better at managing the U.S. relationship with India, a sentiment shared by only 15 percent of Democrats. Conversely, 50 percent of Democrats give Biden the upper hand, compared to 8 percent of Republicans. Twenty-six percent of Democrats and 20 percent of Republicans say both presidents were about the same.

State of U.S.-India Ties

Taking a step back from the Biden administration’s record over the past four years, the survey asks a broad question about the partisan stewardship of the India relationship. Specifically, it asks which American political party does a better job managing U.S.-India relations (see figure 6). Forty-one percent of respondents say the Democratic Party while 24 percent name the Republican Party. One-quarter of all respondents perceive no difference between the two parties, while another 9 percent do not express an opinion.

The 2020 IAAS asked the same question, and the data suggest there has been only modest movement over time. In 2020, 39 percent of respondents reported that the Democratic Party does a better job on U.S.-India relations while 18 percent believed the Republican Party is better. Twenty-six percent said it made no difference, while another 16 percent reported they did not know.

Because the 2024 IAAS was fielded before the U.S. election, it also asks two questions about the prospects for U.S.-India ties under a putative Harris or second Trump administration (see figure 7). Fifty-three percent of respondents say U.S.-India ties would become stronger if Harris was elected, 15 percent state they would get worse, and 32 percent report they would not change. Respondents are somewhat less bullish on prospects under a second Trump presidency. Forty percent report ties would improve, 26 percent report they would worsen, and 34 percent feel they would be unchanged.

One of the thorniest issues that has cropped up in the bilateral relationship is India’s involvement in an alleged “murder-for-hire” plot targeting a Khalistani activist who is an American citizen on U.S. soil.5 U.S. prosecutors charged a former Indian intelligence officer, Vikash Yadav, with allegedly masterminding the plot. The allegations threatened to derail U.S.-India ties. Although the diplomatic fallout of the indictments was effectively contained, it nevertheless fueled an impression inside the BJP and among backers of the ruling party in India that the U.S. “deep state” was conspiring to undermine the Modi government.

To gauge the diaspora’s views on the matter, the survey first asks respondents whether they were aware of the Justice Department’s charges filed against an Indian national in the alleged assassination plot. Only around half (51 percent) respond in the affirmative. This is noteworthy given the media attention this incident received, both in the United States and in India. But it also supports the prevailing wisdom that most people living in the United States do not pay close attention to the details of foreign policy or consider it a top-tier election issue.

The survey then asks respondents whether the Indian government would be justified in assassinating a U.S. citizen on U.S. soil if it believed this person was promoting a violent separatist movement in India (see figure 8). A bare majority—51 percent—respond that India would not be justified in taking such action. Twenty-six percent say it would be justified.

The survey also probes respondents to see if they hold symmetrical views on the U.S. government undertaking similar activities on India soil in the face of a separatist threat. The responses are virtually identical: 50 percent say the United States would not be justified, and 28 percent say it would be. Therefore, a bare majority of respondents believe that targeting separatists on the other country’s soil, specifically when those separatists are citizens of the other country, is not justified.

Views on the Israel-Hamas War

Few foreign policy issues were more front and center in the 2024 U.S. presidential election than the Israel-Hamas war. Many progressive voices and Arab-American groups felt that the Biden administration had not fully exercised its leverage with Israel, contributing to a humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza. There is compelling evidence to suggest that many traditional Democratic voters sought to sanction the party for not doing more to put an end to the Gaza crisis. On the other side, some conservative commentators and Republican politicians argued that the Biden administration did not provide enough support to Israel during the war, undermining a key U.S. ally in the region.

To explore this set of issues, the survey first asks respondents about their own views. Specifically, it asks about where respondents’ sympathies lay in the ongoing conflict on a spectrum ranging from “entirely with the Israeli people” to “entirely with the Palestinian people” (see figure 9). Twenty-nine percent report their sympathies mostly or entirely rest with the Israeli people. On the opposite end, 35 percent of respondents state their sympathies mostly or entirely rest with the Palestinian people. Twenty-four percent adopt the middle position, indicating that their sympathies rest equally with both.6

There are clear partisan differences in respondents’ views (see figure 10). Democrats, on balance, are more likely to side with the Palestinian people (45 percent) compared to Republicans (30 percent). Conversely, Republicans are more likely to side with the Israeli people (46 percent) compared to Democrats (29 percent). Roughly similar proportions (26 percent of Democrats and 23 percent of Republicans) assumed the middle ground position.7

With regards to the Biden administration’s approach to the conflict, 40 percent of respondents judge the administration to have favored the Israeli people too much, whereas only 13 percent perceive that it favored the Palestinian people too much (see figure 11). Roughly one in four respondents (26 percent) report that the administration struck the right balance between the two sides. On this question too, there is a clear partisan tilt. Forty-eight percent of Democratic respondents feel the administration was too pro-Israel compared to 31 percent of Republican respondents. On the other hand, 31 percent of Republicans report that the administration’s policy was too pro-Palestinian, a view shared by just 8 percent of Democrats.

India’s Trajectory

The survey inquires about respondents’ views on India and its political trajectory (see figure 12). Forty-seven percent of respondents feel India is politically on the right track, 32 percent feel it is on the wrong track, and 21 percent cannot say. These numbers represent a significant shift from the 2020 IAAS. Four years ago, respondents’ assessments were markedly more pessimistic, with 36 percent believing India was on the right track and 39 percent reporting it was on the wrong track.

Interestingly, in the 2024 IAAS, U.S.-born respondents appear more bullish about India’s direction than foreign-born respondents. Fifty-five percent of U.S.-born respondents feel India is headed in the right direction as opposed to 42 percent of foreign-born respondents. Roughly equal shares of both categories of respondents—about one in three—indicate India is on the wrong track. Immigrants are also much more likely than their U.S.-born peers to say that they do not know (25 percent versus 15 percent).

The survey also asks about Indian Americans’ views of India’s current policy direction (see figure 13). Forty-six percent of respondents report that they are either strongly or somewhat supportive of the present government’s policies. Thirty-six percent report they are somewhat or strongly critical of the government’s policies. Eighteen percent express no opinion. These numbers are broadly in line with respondents’ “right track/wrong track” assessments.

One possible explanation for the relatively more bullish assessment of India in 2024 is that respondents were heartened by the results of the 2024 election, which resulted in a more evenly divided Parliament and greater dispersion of political power. Indeed, some observers interpreted the result of India’s 2024 general election as giving a fillip to democracy since the outcome produced a coalition government and more robust opposition in Parliament.

Four in ten members of the Indian American diaspora agree with this sentiment (see figure 14). Forty-one percent of respondents report that the 2024 election made India much or somewhat more democratic. On the other hand, 28 percent take the opposite view—that India is much or somewhat less democratic in the aftermath of the general election. Fourteen percent of all respondents do not view the 2024 election as changing India’s democratic character in either direction. One must treat this finding with caution, however, since “democracy” is an amorphous concept and can mean multiple things to multiple people.

While the preceding data points suggest a more positive outlook toward India’s domestic developments, one of the authors has previously highlighted multiple factors, including the concentration of executive power in the prime minister’s hands, rising intolerance of dissent, and growing Hindu majoritarianism, as inimical to India’s democracy. The last issue has perhaps been the greatest focus of debate and discussion insofar as India’s domestic affairs are concerned.

To probe Indian Americans’ views on Hindu majoritarianism, the survey asks respondents to reflect on a controversial incident that took place during last summer’s campaign. Specifically, the survey presents respondents with the following informational prompt: “At an April 2024 campaign rally, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi referred to Muslims as ‘infiltrators’ and warned that an opposition victory would result in Hindus’ land and mangalsutras (wedding necklaces) being forcibly redistributed.” The survey then asks whether respondents agreed with the notion that this language was an example of growing threats to minorities in India (see figure 15). Seventy percent of respondents, a strikingly large number, either strongly or somewhat agree that Modi’s statement exemplified the growing threat to minorities in India. Just 31 percent of respondents disagree with the notion.

One might expect there to be significant variation on this question, based on respondents’ religious identities. Indeed, a religious disaggregation does show some variation, but less than one might expect (see figure 16).

Among diaspora respondents, Hindus are the least likely to agree that Modi’s speech exemplifies the growing threat to minorities, but only in relative terms: two-thirds of Hindus agree with the proposition. That contrasts with 71 percent of Christians, 75 percent of Muslims, and 74 percent of respondents from other religious categories. On the other side of the ledger, 25 percent of Muslims disagree with the idea that Modi’s language exemplifies the anti-minority threat, while 34 percent of Hindus feel the same. Christians (29 percent) and others (26 percent) land in between these two poles.

Political Leadership and Parties

Moving beyond broad assessments of the country’s direction, the survey asks respondents which political party in India they most closely identify with (see figure 17). Fifty-one percent, slightly more than half, reply “don’t know” to this question, suggesting that many Indian Americans maintain a distance from Indian political attachments.

The BJP remains the most popular party among Indian Americans, with 28 percent of respondents identifying with the party. Twenty percent identify with the Indian National Congress Party, the principal opposition party, and just 1 percent identify with a third party. In the 2020 IAAS, 32 percent of respondents supported the BJP, 12 percent supported the Congress Party, and 11 percent identified with a third party.8

The data suggest that the BJP remains the diaspora’s favored party, but the gap with the main opposition party, the Congress, has narrowed compared to 2020. Given this fact, how have Indian Americans’ views of Modi evolved since 2020 (see figure 18)? The survey finds that 47 percent of respondents approve of Modi’s job in office (36 percent strongly approve and 11 percent approve), while 34 percent disapprove (23 percent strongly disapprove and 11 percent disapprove). An additional 19 percent express no opinion either way.

In the aggregate, Modi’s approval ratings among the diaspora have not budged much in four years. In 2020, 50 percent approved of the job Modi was doing (35 percent strongly approved and 15 percent approved) and 31 percent disapproved (22 percent strongly disapproved and 9 percent disapproved).

However, it is possible that the aggregate numbers could mask underlying variation among various demographic groups. To explore this possibility, figure 19 assesses changes in the level of support for Modi by key demographic categories, such as age, education level, income, gender, religion, citizenship, and partisanship. Five findings stand out.

First, Modi has experienced a boost in support among the youngest respondents. In 2020, just 35 percent of respondents under the age of thirty approved of Modi’s job. Four years later, this number stands at 49 percent, a 14 percentage point increase. In contrast, Modi’s support has declined by 5 percentage points among those in the thirty to fifty age bracket while it has dipped by 9 percentage points among those over fifty. These findings bear a striking similarity to younger Indian Americans’ shift toward Trump and the Republican Party, as reported in the authors’ October 2024 study. The precise drivers of this shift require further investigation.

Second, Modi’s popularity has dipped sharply among those at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum. Among respondents without a college education or whose annual household income is below $50,000, Modi’s support has declined by 8 and 13 percentage points, respectively. On the other hand, for those with a household income above $100,000, Modi’s approval rate has inched up from 51 to 55 percent.

Third, a gender gap in support for Modi has emerged since 2020. Four years ago, male and female support for Modi were indistinguishable. In 2024, male support has slightly increased from 49 to 51 percent, while female support has waned from 50 to 42 percent.

Fourth, among religious groups, Modi’s support is down among Hindus (69 to 64 percent) and Christians (33 to 24 percent) while virtually unchanged for Muslims and respondents from other religions.

Finally, the 2024 IAAS reveals a fall in support for Modi among noncitizens as compared to U.S. citizens. In 2020, 49 percent of citizens and 54 percent of noncitizens approved of Modi’s performance. Four years later, citizen support is unchanged while support among noncitizens has fallen from 54 to 40 percent.

To gauge support for prominent political leaders and organizations in India beyond Modi, the survey employs a question pioneered by the American National Election Studies (ANES). For many years, the ANES has included a “feeling thermometer” question whereby respondents are asked to rate political parties or individual leaders on a scale of zero to one hundred. Ratings between zero and forty-nine mean that respondents do not feel favorable toward the person or do not care for the person or entity. A rating of fifty means that respondents are indifferent toward them. And ratings between fifty-one and one hundred mean that respondents feel favorable and warm toward them. In short, the higher the score, the greater the favorability rating.

The 2024 IAAS applies this question to Indian political groups and figures (see figure 20). Modi leads the pack with a rating of 52, which places him marginally on the “warm” end of the spectrum. Rahul Gandhi and his Congress Party both earn a 48. The BJP and the INDIA Alliance both receive a 49. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the BJP’s ideological mentor, receives a 42. All told, there is not much variation in scores across the spectrum.

When considering similar data from the 2020 IAAS, the degree of clustering seems to have grown. Compared to 2020, the ratings for Modi, the BJP, and the RSS have modestly dipped while the corresponding numbers for Congress and Gandhi have marginally inched upward. However, the differences are small and not statistically meaningful.

Conclusion

The 2024 IAAS reveals that Indian Americans broadly support the overall trajectory of U.S.-India ties and favorably assess the Biden administration’s stewardship of the bilateral relationship. Although opinion is hardly uniform, four in ten respondents believe the Biden administration adequately supported India during its four years in office.

Although Indian Americans shifted to the right politically ahead of the 2024 U.S. election, many remain concerned about what the future holds for U.S.-India ties under a second Trump administration. Interestingly, the allegations of an Indian government plot to target and kill a prominent Khalistani supporter in the United States are not as widely known in the community as one might expect. However, only a small minority of respondents believes that such official Indian government action, if undertaken, would be justified.

Of course, Indian Americans’ views on foreign policy extend beyond India and the subcontinent. Few foreign policy issues dominated the U.S. election news cycle as significantly as the war in Gaza. There is no consensus among Indian Americans on this conflict. The diaspora’s sympathies appear divided between the Israeli people and the Palestinian people. Some of this variation is accounted for by partisan ties, with Democrats more likely to express sympathy with the Palestinian cause and Republicans the opposite.

When it comes to India’s domestic transformations, Indian Americans appear more bullish in 2024 than they were in 2020. Forty-one percent of respondents believe that India has become more democratic since its 2024 general election. While support for Modi has hardly budged over the past four years, there has been significant shift among key demographics. Older respondents, women, those with a lower socioeconomic status, and noncitizens are less supportive of Modi in 2024 than they were in 2020 while younger respondents are more supportive. Indian Americans, by and large, do not possess clear partisan identities in India. But, to the extent they do, they tilt toward the BJP.

While this study offers a deep dive into the diaspora’s foreign policy attitudes, it does not say much about are the social realities of the community. How do Indian Americans engage in civic and political life? What role do religion and caste play in their daily lives? Do Indian Americans experience significant discrimination in their daily lives? And how does the diaspora weigh the cross-pressures of “becoming American” with a desire to maintain their “Indian-ness”? These questions, and several others, are the focus of the third and final study in this series.

Appendix A: Methodology

Respondents for this survey were recruited from an existing panel administered by YouGov. YouGov maintains a proprietary, double opt-in survey panel comprised of 500,000 U.S. residents who are active participants in YouGov’s surveys.

Online Panel Surveys

Online panels are not the same as traditional, probability-based surveys. However, due to the decline in response rates, the rise of the internet, smartphone penetration, and the evolution in statistical techniques, nonprobability panels—such as the one YouGov employs—have quickly become the norm in survey research.9 In the 2024 U.S. election cycle, for instance, the Economist partnered with YouGov to track the presidential election and political attitudes using a customized panel.10 YouGov’s surveys have been repeatedly found to be among the most reliable in predicting U.S. voting behavior due to their rigorous methodology, which is detailed below.

Respondent Selection and Sampling Design

The data for this study are based on a unique survey of 1,206 people of Indian origin. The survey was conducted between September 18 and October 15, 2024. To provide an accurate picture of the Indian American community writ large, the full sample contains both U.S. citizens (N=982) and non-U.S. citizens (N=224).

Sample Matching

To produce the final dataset, respondents were weighted to a sampling frame on gender, age, race/ethnicity, and education. The sampling frame is a politically representative modeled frame of U.S. adults, based upon several reliable national surveys and administrative datasets: the American Community Survey (ACS) public use microdata file, public voter file records, the 2020 Current Population Survey (CPS) Voting and Registration supplements, the 2020 National Election Pool (NEP) exit poll, and the 2020 Cooperative Election Study (CES), including demographics and 2020 presidential vote.

To generate the weights, the respondent cases and the frame were combined, and a logistic regression was estimated for inclusion in the frame. The propensity score function included age, gender, race/ethnicity, years of education, and region. The propensity scores were grouped into deciles of the estimated propensity score in the frame and post-stratified according to these deciles.

The weights were then raked on education, region, and a two-way stratification of age and gender to produce the final weight.

Data Analysis and Sources of Error

All the analyses for this study were conducted using the statistical software R and employ sample weights to ensure representativeness.

The analyses in this study focus on the entire sample of citizens and noncitizens (N=1,206), which has a margin of error of +/- 3 percent. All margins are calculated at the 95 percent confidence interval.

Figure 21 shows the geographic distribution of survey respondents by state of residence.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge numerous individuals and organizations for making this study possible. We are grateful to Alexander Marsolais, Clara Cullen, Alexis Essa, and their colleagues at YouGov for their help with the design and execution of the survey. Caroline Mallory also aided with the design of the survey.

This project has been reviewed and approved by the American University Institutional Review Board (Protocol #IRB-2025-32).

At Carnegie, we owe special thanks to Lindsay Maizland for editorial support for this paper. We would also like to acknowledge Amanda Branom and Jocelyn Soly for lending their graphic design talents to the data visualization contained in this study. Sharmeen Aly, Alana Brase, Aislinn Familetti, Clarissa Guerrero, Jessica Katz, Heewon Park, Mira Varghese, Katelynn Vogt, and Cameron Zotter contributed design, editorial, and production assistance.

While we are grateful to all our collaborators, any errors found in this study are entirely the authors’.

Notes

1This study reports sample sizes as raw totals, but all analyses include sampling weights. Therefore, the numbers discussed here are weighted, unless otherwise noted.

2The discrepancies in reported median household income between the 2024 IAAS and the 2023 ACS could be due to a range of factors, including varying definitions, recall bias, and question wording.

3These numbers are broadly in line with the findings of the 2020 IAAS. In 2024, Indian Americans are slightly more likely to say that the United States is too supportive of India (12 percent in 2020 versus 17 percent in 2024) but also slightly more likely to report that the United States is not supportive enough (24 percent in 2020 versus 28 percent in 2024). The share of those expressing no opinion declined by 8 percentage points (from 24 to 16 percent).

4There is a large body of research showing that partisanship colors how individuals assess leaders, policies, and the overall state of the country and economy.

5On November 23, 2023, U.S. federal prosecutors charged Nikhil Gupta with conspiring to kill Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, a U.S. citizen, on American soil. Pannun is an outspoken advocate of the Khalistan movement, which seeks an independent homeland for people of the Sikh faith in the Indian state of Punjab. Indian authorities classify Pannun as a terrorist for inciting violence. The allegations came on the heels of the alleged assassination of Canadian Khalistani activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar, who was shot dead outside a gurdwara in a Vancouver suburb in 2023.

6A February 2024 survey of Americans conducted by the Pew Research Center echoed some, but not all, of the 2024 IAAS’s findings. In the Pew survey, 31 percent of respondents reported their sympathies mostly or entirely rested with the Israeli people, while 16 percent reported their sympathies mostly or entirely rested with the Palestinian people. Twenty-six percent selected the middle ground position, 8 percent said their sympathies rested with neither side, and 18 percent did not have an opinion. In comparison, the 2024 IAAS reveals much stronger support for the Palestinian cause.

7Data from the 2024 Pew survey suggest that American respondents who identify as Democrats are not as likely as Indian American Democrats to side with the Palestinian people. According to Pew, a greater share of Democrats reported that their sympathies were divided between the Israeli people and the Palestinian people.

8The 2020 IAAS explicitly enumerated seven non-Congress and non-BJP options from which respondents could select. The 2024 IAAS simply gives respondents the option to select “other.”

9For an accessible introduction to this survey method, see Courtney Kennedy, Andrew Mercer, Scott Keeter, Nick Hatley, Kyley McGeeney, and Alejandra Gimenez, “Evaluating Online Nonprobability Surveys,” Pew Research Center, May 2, 2016, https://www.pewresearch.org/methods/2016/05/02/evaluating-online-nonprobability-surveys. According to YouGov, its panel outperformed its peer competitors evaluated in this Pew study. See Doug Rivers, “Pew Research: YouGov Consistently Outperforms Competitors on Accuracy,” YouGov, May 13, 2016, https://today.yougov.com/topics/finance/articles-reports/2016/05/13/pew-research-yougov.

10For details on the Economist-YouGov collaboration or to compare some of our findings on Indian Americans with the American population more generally, visit https://today.yougov.com/topics/politics/explore/topic/The_Economist_YouGov_polls.

.jpg)

.jpg)