Introduction

Since the 2011 uprising, which ousted longtime president, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, relations between the Tunisian state and large private enterprises have undergone significant transformations. The period from 2011 to 2021 saw the growing autonomy of big business, which became politically influential, effectively earning veto power over economic decisions that could impinge on its privileges and rent-seeking. Because Tunisia’s politico-business elites refused to put the economy at the service of the majority of the people, a populist wave took shape against them. Kais Saied, a newly ascendant politician with a background in the legal profession, rode this wave, winning the presidential election in 2019. In 2021, following his dismissal of the government and suspension of parliament, he promulgated a new constitution that concentrated power in his hands. This ended the country’s short-lived democratic experiment (2011–2021), strained state-business relations, and led to the private sector’s marginalization both in politics and in economic policymaking.

However, although Saied antagonized large private enterprises with an anti-business and anti-elite populist narrative, he refrained from overhauling competition and regulation frameworks that would have constrained their rent-seeking. Nor did he create economic opportunities for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). In effect, Saied for the most part preserved the status quo, thereby hindering the possibility of an economic recovery. This reflects the priorities of his regime, which is primarily focused on political survival. The regime maintains its survival by relying on banks to finance the state’s annual budget deficit. This has in turn allowed large private enterprises, which wield influence over the financial sector, to lessen the impact of the partial marginalization to which they are subjected.

A Declining Private Sector Overshadowed by Political Influence

Although Tunisia’s private sector had experienced a steady decline since the beginning of the twenty-first century, matters worsened dramatically in the post-uprising decade. During this period, growth dropped to an average of just 0.9 percent, as opposed to 4.4 percent in the previous decade. The deterioration of Tunisia’s economic performance is due in part to external shocks, including the loss of Libya as a major trade partner owing to its civil war (2014–2020), domestic political assassinations in 2013, terrorist attacks on Tunisian soil in 2015 and 2016, and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2021. Yet the main reason for Tunisia’s economic doldrums is a dysfunctional political system that has resisted a structural transformation of the economy. The productive base remains stuck in low value-added activities, firms are stagnating, and the economy lacks the dynamism needed to create the number and types of jobs that appeal to the country’s youth.

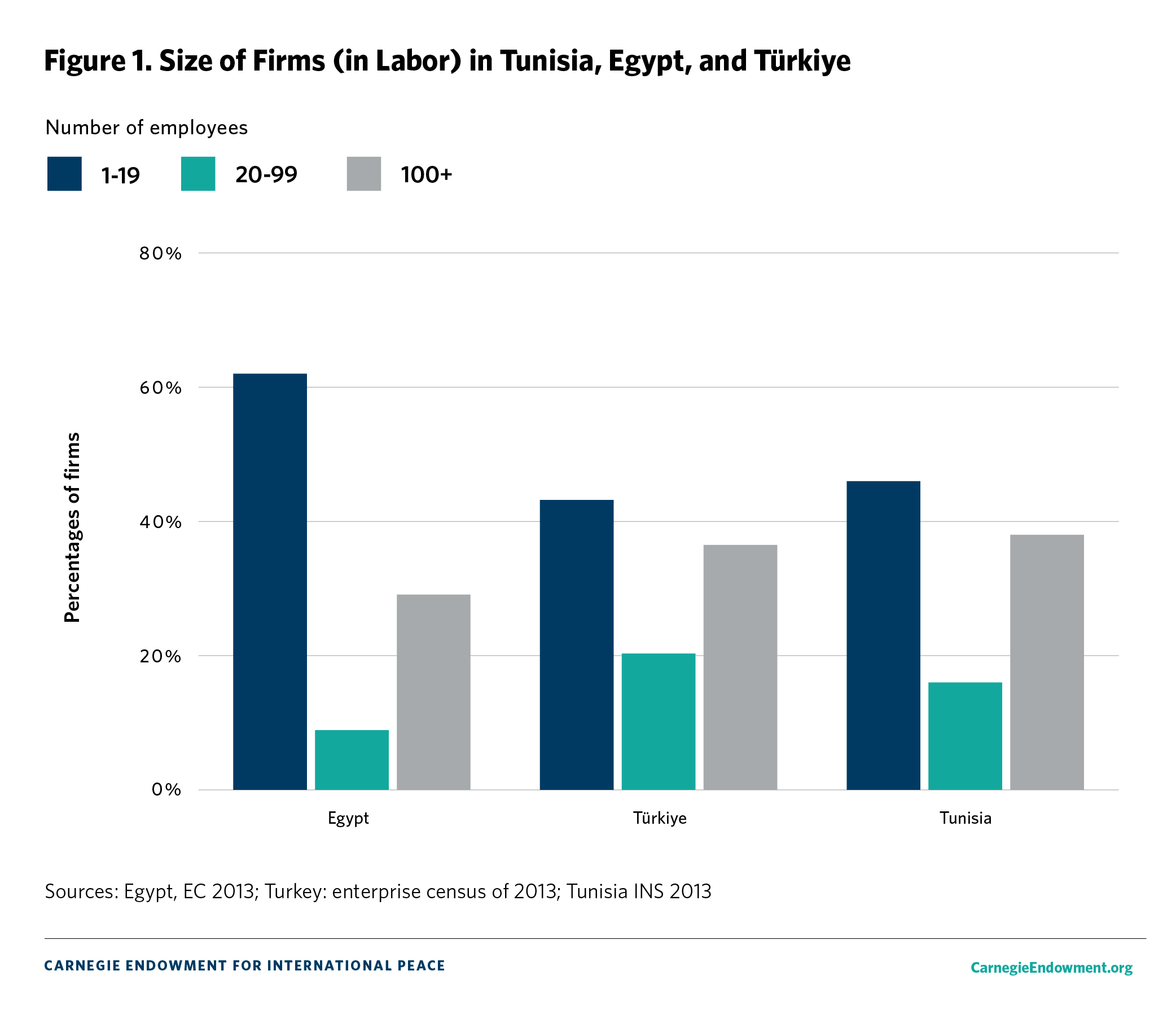

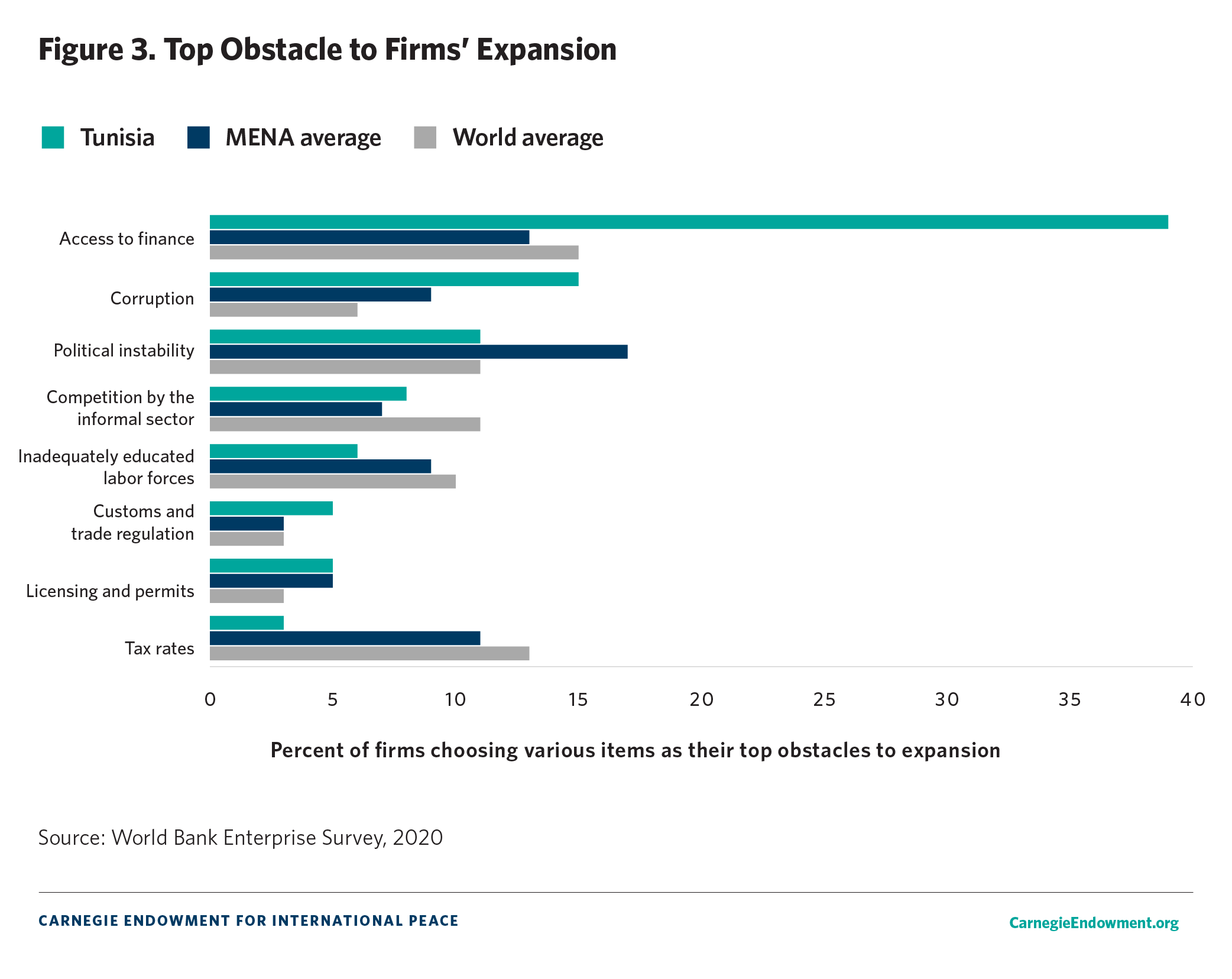

The lack of market dynamism is reflected in a corporate landscape dominated by large companies, both public and private, and by a multitude of informal small firms. The economy sorely lacks medium-sized firms—which tend to be the most dynamic job-creators worldwide—due to unfair competition from both informal and dominant privileged firms. This dearth of medium-sized companies is the main reason for the lack of innovation and the low level of economic dynamism. The post-2011 political elites, including Saied, failed to dismantle the bureaucratic barriers restricting competition and market access and to reform regulatory frameworks that encourage rent-seeking and market capture. The World Bank Enterprise Surveys reveal that firms operating in Tunisia face two key constraints: high levels of corruption and a significant degree of political and macroeconomic risk (see Figure 1).

Both during Ben Ali’s rule and after his fall, business cartels dominated key economic sectors, capturing markets and guarding against new entrants into core industries, services, and banking. According to the World Bank, under Ben Ali’s regime, politically connected enterprises played a significant role in sectors where entry was heavily regulated. These firms accounted for 10 percent of jobs, 39 percent of output, and 53 percent of net profits. They were protected from competition and had privileged access to bank credit. The democratization process that began in 2011 did not fundamentally change the situation, despite the state’s seizure of firms owned by Ben Ali and his family. In a context of fragile political pluralism marked by a growing Islamist-secularist divide and a relative neglect of economic governance—given that constitutional and political matters took precedence—these enterprises succeeded in maintaining an almost unchanged regulatory and competition framework. They did this in three ways. First, many prominent businessmen took to funding political parties, leveraging the latter’s need for financial support to gain influence. Second, some businessmen became directly involved in politics, running for parliamentary elections and playing crucial roles in key committees, such as the Finance Committee. Finally, large businesses made significant investments in the newly liberated media landscape, using various outlets to shape public opinion and exert influence over politicians.

The severe political crisis of 2013, triggered by political assassinations and the near collapse of the democratic experiment, provided business elites with an opportunity to expand their influence. They did this in large part through the Tunisian Union of Industry, Trade, and Handicrafts (UTICA), and the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT). After decades of aligning with the authoritarian leadership of Habib Bourguiba (1956–1987) and Ben Ali, UGTT and UTICA seized on the crisis to remain relevant in a time of democratization. The two unions successfully pushed the political elite, both Islamist and secular, to accept a national dialogue that paved the way for the 2014 constitution and general elections.

With post-2014 governments often eager to secure the unions’ support to remain in office, UGTT and UTICA effectively became kingmakers. And, given that UGTT was focused on protecting and expanding its membership rather than transforming the country’s economic structure, and UTICA was beholden to big business, they opposed a development strategy that could have initiated thoroughgoing economic reform and consolidated democracy. The membership base of the UGTT expanded significantly due to the creation of more than 155,000 new public-sector jobs after 2011, as part of a government program to stave off social unrest. Meanwhile, UTICA secured advantages in taxation, regulation, and market access for large private enterprises, despite the deleterious effects of such policies on the economy. Large businesses have been favored by post-2014 governments, particularly through several budget laws passed between 2014 and 2019 that granted tax exemptions and investment incentives. Despite pressure from international financial institutions and Tunisian nongovernmental organizations to reform the competition framework and improve market access for SMEs and new entrepreneurs, little progress was made due to resistance from influential business elites and the accommodating stance of political elites toward them.

In 2017, the government of prime minister Youssef Chahed proposed austerity measures aimed to reduce the annual budget deficit as well as cut the national debt, as part of the implementation of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) reform program adopted in 2016. The government sought to distribute the adjustment burden between labor and capital by freezing public-sector hiring and raising corporate taxes. However, representatives of UGTT and UTICA resisted, forcing the government to back down. As a result, the IMF halted the disbursement of the loan and the reform program went nowhere. The situation set the stage for a slow deterioration of economic conditions, generated insecurity, and ultimately led to the appeal of populism.

A Financial Sector at the Service of the State

Beginning in 2022, Saied concentrated power in his hands through a new, president-centric constitution that granted him broad authority and marginalized legislative bodies, labor unions, and political parties. When it came to the economy, he focused on servicing the spiraling national debt, for which purpose he hiked taxes and repeatedly dipped into the country’s foreign reserves. Saied also sought to bring big business to heel by launching an anti-corruption campaign aimed at squeezing money out of the elites and by promoting newly established communal companies. The latter are state-funded and state-controlled enterprises designed to compete with private-sector firms in part by building patronage networks.

Saied’s strategy failed to stem the country’s economic decline, much less foster growth. In fact, it made things worse. His attempt to cut down big business ended up paralyzing the private sector—crucial to virtually any successful economy—as a whole. Moreover, although the business elites have lost some of their influence in Tunisia, they have managed to protect their core interests by supporting the regime in meeting its financing obligations. The regime found itself in need of these elites’ assistance in pressuring the banking sector to help finance the government’s annual budget. Moreover, with the exception of introducing a wealth tax in 2023 targeting real estate, Saied’s regime has largely preserved existing tax legislation. Corporations—particularly offshore entities—and wealthy individuals earning income from interest and capital gains continue to benefit from tax advantages.

Meanwhile, the scarcity of external funding sources has made foreign exchange reserves the go-to option for covering the country’s needs, including imports, debt servicing, and other financial obligations. Since 2022, the rationing of foreign exchange reserves, undertaken for the purpose of preserving funds, has severely constrained firms’ ability to import much-needed production materials. This has led to a significant decline in revenue for businesses that rely on foreign exchange to import goods and pay their suppliers, deepened economic stagnation, and further marginalized the private sector.

State-business relations became extremely strained after Saied initiated a selective crackdown on major businessmen in 2023. Justifying his move by pointing to the failure of the post-2011 transitional justice process to recover fortunes illicitly acquired under the Ben Ali regime, he created a process that involves an administrative settlement in which the accused party commits to repaying the total sum that the penal reconciliation committee determines was illegally acquired, plus interest. However, in the two years since it has been in place, the process has proven ineffective. Business elites have largely rejected it, with many fleeing the country to avoid prosecution or ending up in jail for refusing to cooperate.

In attempting to address urgent demands for job creation, poverty alleviation, and income generation, Saied has skirted the private sector in favor of communal companies, which operate in sectors such as services, transportation, and agriculture. This is also an attempt to build a clientelist support base; Saied has transferred land ownership from the state to his supporters and redistributed wealth from business elites to his base via bank credits. However, the state bureaucracy has increasingly obstructed these and other initiatives, which it views as demagogic and counterproductive. For example, bureaucratic opposition to Saied’s proposed labor law reforms, which aim to end subcontracting and fixed-term contracts in the private sector, led to a prolonged and inconclusive consultation process between various government departments and ministries. This ultimately resulted in a government reshuffle, with Ahmed Hachani’s cabinet replaced by one led by Kamel Maddouri, who was tasked with implementing these labor reforms. However, the process had to restart from the beginning, with consultations between the government and the corporate unions, namely UGTT and UTICA.

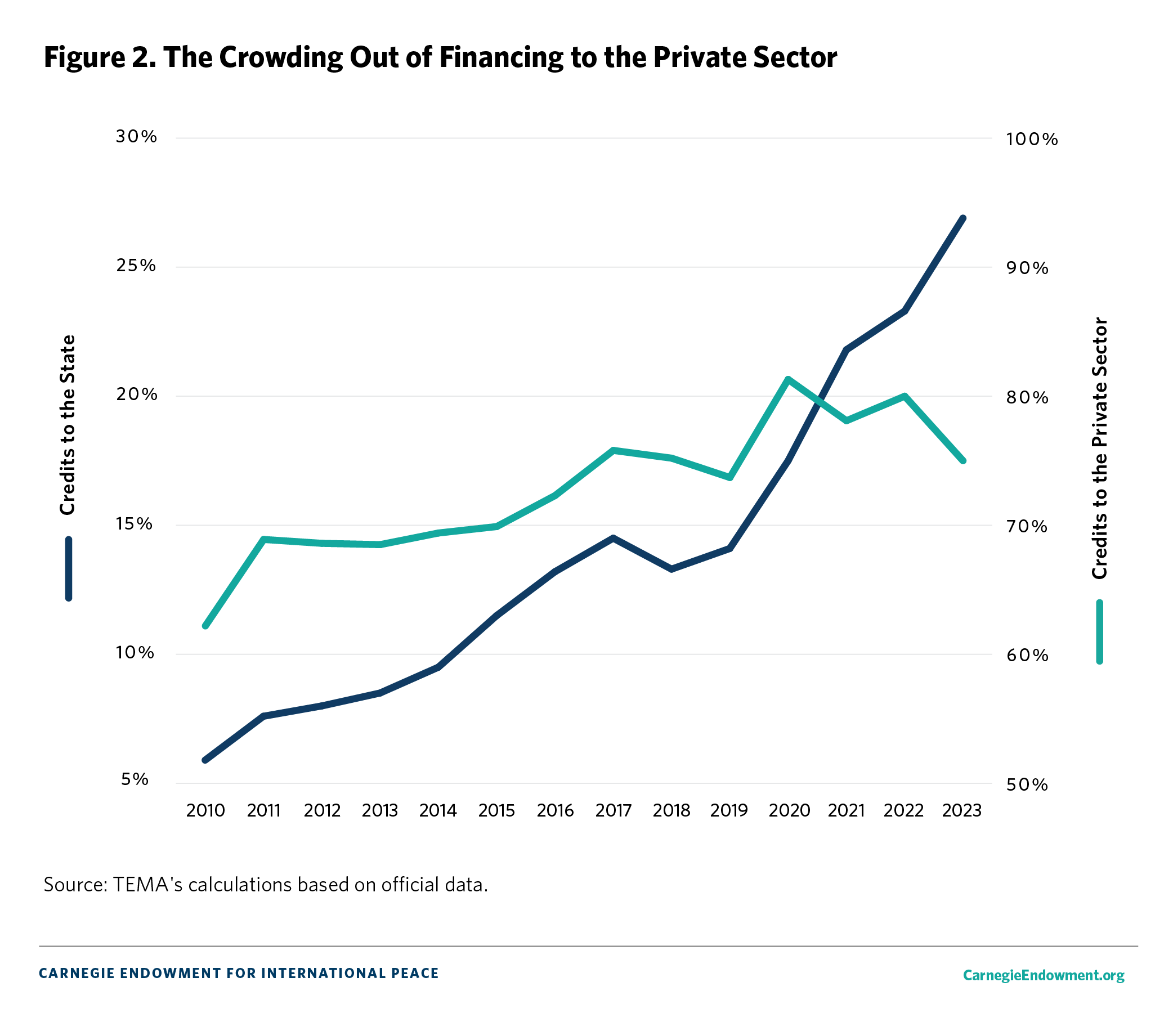

In its bid to finance its annual budget deficit, the government has also resorted to selling sovereign bonds to Tunisian banks. The banking sector’s net claims on the state have almost doubled over the past five years, amounting to 23.6 percent of GDP by the end of 2023. Given the attractive returns, a credit risk that is deemed low (in comparison to lending to the private sector), and the support for liquidity provided by the Central Bank in times of need, the banking sector has welcomed the growing exposure to national debt. Bank credits granted to the state increased by 24.8 percent in 2023, while credits to the private sector increased by only 2 percent—the lowest growth rate of bank financing of the economy in at least two decades.

The increase in domestic borrowing enables big business to protect itself. Five holdings, most of them family-owned businesses across several sectors, generate more than 60 percent of the revenue of the country’s largest private companies. Their grip on the economy is strengthened by their direct ties to banks: they are shareholders in seven of the twelve publicly traded banks. This secures them easy access to credit lines from the banks and effectively shuts SMEs out of the process. It also grants them political leverage over Saied’s regime, enabling them to protect their interests and blunt further attempts at their marginalization in exchange for prevailing upon the banks to provide the funding the state requires to meet its financing needs. Yet this is very risky; in case of default by the state, the repercussions on the banking sector would be disastrous.

The Private Sector Needs an Overhaul

If Tunisia’s decisionmakers are to build a development strategy that can address their country’s structural weaknesses, they must revive its private sector. Democratization and reform are key prerequisites for this to happen. Broadly speaking, four measures would go a long way toward achieving both. The first is macroeconomic stabilization, which would reduce economic uncertainty and improve access to finance and imports for SMEs, allowing them to grow. The second is improved governance, including reforming the regulation of the economy, which would ensure fair competition and the rule of law. Third is advancing an appropriate development strategy, one that encourages the expansion of large enterprises’ activities to international markets and supports SMEs with incentives to upgrade their use of information technology and robotics, integrates global value chains and attracts foreign direct investment, supports training, and expands research and development. Lastly, Tunisia must adapt to the ongoing green transition in Europe, its major trade partner, particularly with regard to climate policies and decarbonization. Otherwise, with new carbon emissions in place, fewer European companies will purchase products from Tunisia.

Tunisia should reopen discussions with the IMF regarding a homegrown reform program. This is indispensable to meeting the country’s external financing needs, securing funding for SMEs, and reducing the banking sector’s exposure to sovereign risk. A significant number of Tunisian companies do not have access to bank financing. According to the latest edition of the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys, nearly half (45.5 percent) of Tunisian companies consider access to credit particularly difficult, a much higher percentage than in Morocco (34.2 percent) and Egypt (24.6 percent).

Collusion between large enterprises and banks is also a significant issue, as it undermines competition, increases the risk of access to business-sensitive information, and allows large businesses to interfere in credit allocation and investment decisions. With over 30 banks, Tunisia is “overbanked.” Three state-owned banks control 36 percent of the market, and five major banks (including the state-owned ones) account for over 50 percent of the sector. However, despite the large number of banks, none with the capacity to finance major development projects in the country.

Reforming the competition framework through anti-trust legislation is critical to democratizing the economy, aiding the growth of innovative SMEs, and putting an end to the influence of cartels that dominate key economic sectors. Most of these cartels have failed to internationalize, further stifling the space of SMEs to grow and expand. Moreover, the current political nature of state-business relations protect collusion between bureaucratic elites and large private enterprises and encourage rent-seeking and corruption.

Tunisia’s private sector needs to stay abreast of the global reshuffling of value chains and digital transformation. At the global level, many European companies, concerned about geostrategic risks, have begun relocating to regions closer to their countries, to avoid the challenges of dispersed production and risky transportation. This presents Tunisia with opportunities to rethink its development model by integrating into new automotive and pharmaceutical value chains, as well as those of the services sector, which is being profoundly transformed by digitalization. In parallel, the country should upgrade its digital infrastructure and expand the use of mobile and broadband subscriptions.

Tunisia must also adapt to the trend of green protectionism that is emerging in Europe. The European Union is set to gradually implement the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). This policy will require European importers to report the carbon emissions associated with imported goods and purchase carbon credits to offset these emissions. CBAM will be a challenge for Tunisia, yet abundant solar resources could become a key comparative advantage. In theory, the country can leverage its solar resources to develop products made with renewable energy. However, this would require not only revising industrial policies to meet climate and green standards but also making significant investments in renewable energy. If Tunisia fails to keep pace with these changes, the country will end up being marginalized economically and geopolitically.

Conclusion

If Saied does not scrap his modus vivendi with big business, which is driven by his need to fund the government’s annual budget deficit and service the overall national debt in the absence of external financing, economic gridlock will continue. Unfortunately, he has little inclination to break with the business oligarchs, owing to his focus on political survival in the face of increasing economic hardship that will inevitably trigger popular dissatisfaction (an ironic development, given his carefully cultivated populist image). As such, it would be overly optimistic to expect more than minor adjustments—such as increased taxation on large enterprises to ease public anger—on his part. The problem is that Tunisia requires much deeper change. New growth opportunities are emerging globally, and they must be seized through the implementation of sound policymaking. Otherwise, the private sector will decline further, which will in turn jeopardize the country’s economic future.