Few geopolitical alignments are more consequential to global security and world order than the Russia-Iran partnership of defiance. Tehran and Moscow are co-belligerents in two of the world’s deadliest conflicts—in Ukraine and Syria—and play an outsized role in myriad challenges including nuclear proliferation, cybersecurity, authoritarian resurgence, disinformation campaigns, human rights violations, illicit finance, and the weaponization of energy resources. Together they control nearly 40 percent of the world’s proven natural gas reserves and 20 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves.

Connected geographically by the Caspian Sea, Russia and Iran are historical geopolitical rivals with competing national interests and centuries of mutual mistrust. Yet, throughout history, they have occasionally united against common adversaries, including the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire, and now the United States. Perceived U.S. efforts to encircle them militarily and subvert them internally are one basis for their partnership. Wars in Syria and Ukraine have further deepened their military, economic, and diplomatic links.

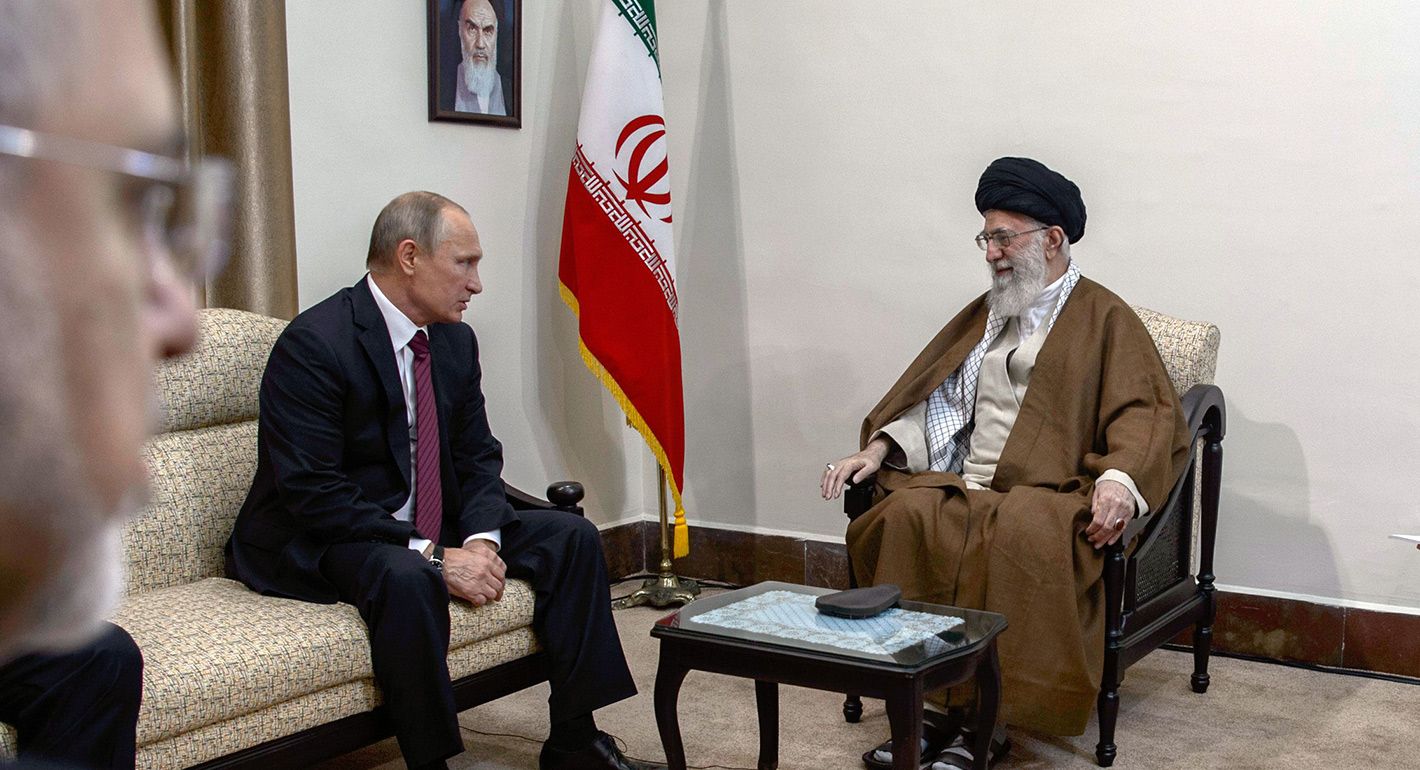

Both countries are ruled by embattled autocrats—eighty-five-year-old Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in Iran and seventy-one-year-old Vladimir Putin in Russia—who have collectively been in power for over five decades. The two men are united in their opposition to the United States and the liberal international order, in particular eastward NATO expansion and America’s political, military, and cultural influence in the Middle East. As Anne Applebaum writes in Autocracy Inc., Putin and Khamenei also share, like many of their autocratic peers, “a determination to deprive their citizens of any real influence or public voice, to push back against all forms of transparency or accountability, and to repress anyone, at home or abroad, who challenge[s] them.”

Despite their competitive national interests and lingering mistrust, the modern-day bond between Moscow and Tehran will not be broken easily. Notwithstanding America’s military and economic superiority, both countries believe the U.S.-led world order is vulnerable and ripe to be challenged. They also perceive America as afflicted with grave political polarization, which they’ve sought to accentuate. U.S. intelligence believes that Moscow has actively sought to help get Donald Trump reelected, while Tehran has actively plotted Trump’s assassination. Perhaps most importantly, both governments currently view their partnership as critical to their internal survival.

So long as Khamenei and Putin remain in power and continue to view the U.S.-led world order as both threatening and vulnerable, their partnership will likely endure. This partnership of defiance and mutual survival poses a significant challenge to global stability and Western influence.

Putin and Khamenei: United by Insecurity

Perhaps more than any other factor, Russian and Iranian concerns about their internal stability, and perceived U.S. attempts to undermine it, have cemented their modern partnership. Both Putin and Khamenei harbor deep-seated fears of color revolutions and have repeatedly resorted to violence to crush the numerous popular uprisings that have threatened their rule. The Arab Spring protests—which began in Tunisia in late 2010 and spread across the Middle East—initially elicited mixed responses from Russia and Iran. Moscow viewed the uprisings as an internal matter, while Tehran self-servingly framed them as an “Islamic Awakening” against Western-backed autocracies. Yet it reinforced the views of both regimes that U.S. advocacy for human rights and democracy promotion were pretexts to interfere in their internal affairs.

The aftermath of the 2011 NATO-led intervention in Libya profoundly influenced both Russian and Iranian foreign policy. NATO was perceived to have exceeded its mandate, leading to Qaddafi’s overthrow and death. This outcome solidified Russian and Iranian concerns about Western-led interventions under humanitarian pretexts. It also significantly influenced their subsequent approach to Syria, where both countries became staunch defenders of Bashar al-Assad’s regime against what they viewed as Western attempts at regime change. Less than a year after the Arab Spring erupted, Russia experienced domestic political upheaval, with anti-government protests following the 2011–2012 Duma elections. Russia drew parallels between these protests, the Arab Spring, and earlier color revolutions, framing them all as examples of Western attempts at regime change.

Putin’s May 2012 return to the presidency was accompanied by a more assertive foreign policy stance, emphasizing Russian sovereignty and resistance to Western influence. Putin’s return also saw a renewed effort to strengthen ties with Iran. This included revisiting military-technical cooperation, with Putin in 2015 reversing his predecessor Dmitry Medvedev’s decision to ban the S-300 missile system as part of the reset with Washington. Moreover, Russia and Iran would increasingly become codependents, reliant on each another for external security and internal survival.

The ripples of the Arab Spring demonstrated the foundation of this partnership: resistance to Western pressure and perceived attempts to impose Western-style democracy. Experiences of domestic unrest, such as the 2011–2012 protests in Russia and the Green Movement in Iran, underscored the vulnerability of both regimes to mass upheaval. The Iranian regime’s repressive capacities have been aided in part by Russian moral support and, more importantly, Russian surveillance technology, including eavesdropping devices, advanced photography devices, lie detectors, and advanced software. “Death to Russia” has been a popular slogan heard at Iranian anti-government protests since 2009.

Concerns about domestic upheaval have been formalized through key agreements that facilitate the exchange of expertise and methods for suppressing public opposition and controlling information flows. In 2014, the two countries’ Ministries of Interior signed an agreement. While ostensibly focused on maintaining public order, the agreement’s broad scope and emphasis on countering “unrest” has effectively created a framework for sharing tactics to quell dissent. This cooperation further expanded into the cyber domain with a 2020 agreement on information security. Though officially aimed at countering cyber threats, the agreement’s expansive definition of these threats has been used by both regimes to justify cracking down on free speech and opposition voices.

Through their collaborative efforts, Russia and Iran have effectively created a system that legitimizes repressive practices under the guise of maintaining public order and national security. Russia and Iran view each other as valuable partners in countering U.S. influence in the Middle East and defending the principle of state sovereignty against external intervention.

Saving Assad

When Arab popular protests in 2011 threatened the stability of the Assad regime in Syria—Tehran’s only enduring regional ally and its bridge to Lebanese Hezbollah—Iran viewed it as an existential threat. “Syria is the 35th province [of Iran],” said Mehdi Taeb, a close adviser to Khamenei. “If we lose Syria, we won’t be able to hold Tehran.” Russia also had significant stakes in the survival of the Assad regime. Syria hosted Russia’s only naval base in the Mediterranean at Tartus, and Moscow viewed Damascus as a key partner in the Middle East.

Initially, Russian and Iranian support took different forms. Iran provided extensive military and financial assistance to bolster Assad’s forces on the ground, deploying Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) advisers and mobilizing Shia militias from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Lebanon (Hezbollah). Russia, on the other hand, wielded its diplomatic clout to shield Assad from international pressure, using its United Nations (UN) Security Council veto to block resolutions targeting Damascus. The Barack Obama administration’s failure to enforce its chemical weapons redline in 2013 signaled to Russia and Iran that the United States had no plans to militarily confront the Assad regime.

In the spring of 2014, when opposition forces gained ground in Syria and the Assad regime’s hold on power appeared tenuous, Russia and Iran heightened their coordination. High-level meetings between Russian and Iranian officials laid the groundwork for a joint military campaign to ensure the survival of the Assad regime. In the summer of 2015, IRGC commander Qassem Soleimani traveled to Russia—in contravention of UN sanctions—to plan a joint military campaign.

Several months later, a combination of Russian airstrikes and Iranian-led ground offensives enabled the Assad regime to reclaim key territories from rebel forces and reassert its control. In August 2016, Tehran even granted Russia access to a military base inside Iran to launch airstrikes in Syria, an unprecedented move for an Iranian government whose constitution prohibits foreign military bases on its territory. Although their collaboration in Syria was fraught with recriminations and mistrust, Russia and Iran achieved their goal of preserving Assad’s rule in Damascus.

What’s more, the Syrian Civil War spawned the establishment of a Russia-Iran joint military commission that institutionalized routine high-level engagements between the countries’ general staffs. It facilitated not only yearly visits among deputies of general staff and operational commanders but also exchanges involving military academies, headquarters, and visits to various military facilities. Many of these networks would prove crucial several years later in helping Russia in its war against Ukraine.

Leveling the Partnership: Ukraine and Drones

Vladimir Putin’s February 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine altered the nature of the Russia-Iran partnership. As Moscow sought to sustain its “special military operation,” it turned to Tehran for critical military support, particularly in the form of drones and ammunition. Putin’s July 2022 visit to Iran marked his first trip to a foreign country outside the former Soviet Union since the start of the war in Ukraine. Khamenei voiced his solidarity with Putin, calling NATO a “dangerous creature” and saying, “had you [Putin] not taken the initiative, the other side would have taken the initiative and caused the war.”

Historically Russia held the dominant position in this partnership, especially in the arms trade, serving as Iran’s primary supplier of military equipment. The prolonged conflict in Ukraine and Western sanctions, however, have impaired Russia’s ability to replenish certain weapons reliant on Western components. This new reality compelled Moscow to seek assistance from Tehran, effectively reversing the usual flow of military technology between the two countries.

Leveraging existing networks, procurement channels, and weapons from Syria, Iran was able to provide Russia with much-needed drones to support its campaign. Iran supplied a diverse array of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to Russia, including the Mohajer-6, the Shahed-131, and the Shahed-136. These UAVs enhanced Russia's capabilities in suppressing Ukrainian air defenses and executing long-range strikes. Iranian personnel were even deployed to Crimea to train and assist the Russian military in operating these weapons.

Tehran also assisted Moscow in establishing domestic production lines for these drones within Russia, though Iran's assistance was not limited to drones. The country made substantial contributions to Russia's ground operations by supplying over 300,000 artillery shells, 1 million rounds of ammunition, various types of artillery rockets, and other military equipment. More recently, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken confirmed that Iran has delivered hundreds of short-range ballistic missiles to Russia in defiance of numerous warnings from U.S. and European officials towards Iran.

The provision of Iranian drones and, more recently, missiles to Russia for its campaign in Ukraine marked a significant evolution in the Russia-Iran relationship. In part, the war itself served as an accelerant to the already burgeoning Russia-Iran ties, propelling their cooperation to new heights. After Russia’s invasion, the frequency of high-level political and commercial delegations traveling between Moscow and Tehran increased dramatically. In return for Iran’s support, Russia has bolstered Iran's military capabilities in several areas. Iran has made notable progress in acquiring advanced conventional weaponry from Russia, allowing it to achieve some of its defense officials’ long-standing goals. In November 2023, Tehran secured deals for Su-35 fighter jets, Yak-130 training aircraft, and Mi-28 attack helicopters, though only the Yak-130s have been delivered so far.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has provided Iran with invaluable technical and operational insights, particularly regarding the deployment of missiles and UAVs against modern air defense systems. Iranian-made UAVs have been extensively used in Ukraine against Western surface-to-air missile systems and electronic warfare capabilities. In essence, Ukraine has served as a real-world testing ground, which has allowed Iran to assess and refine its drone technologies against some of the most advanced defensive systems currently in use.

The war in Ukraine has strengthened Putin’s and Khamenei’s determination to realize a long-standing goal: a multipolar world order that challenges Western dominance. This alignment has been further strengthened by the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, which both nations view as a catalyst for reshaping global power dynamics. Moscow and Tehran see the Ukraine war as a pivotal moment to rally non-Western countries around their alternative vision of international relations.

In Pursuit of a Post-American World

Both Russian and Iranian leadership have made clear their aspirations for a post-American world, one in which U.S. political, economic, and military power has been significantly diminished. “One of the areas where the two parties can cooperate includes containing the U.S.,” Khamenei told Putin in a 2018 meeting in Tehran, “because the U.S. poses a threat to the humanity, and it is possible to contain it.” Putin similarly views Iran as important to the “formation of a more equitable multipolar world order.” Although the two countries have often successfully defied U.S. censures and challenged global norms with impunity, they have had very limited traction building an alternative political and economic order.

Economically, their shared experiences of Western sanctions—Russia and Iran are two of the most sanctioned nations in the world—has fostered a sense of solidarity, driving them to try to develop alternative financial systems that would allow them to evade economic restrictions. Both countries view sanctions as a tool of U.S. unilateralism, designed to pressure them into compliance with Washington’s diktats. Especially after the war in Ukraine, this shared grievance has motivated them to seek ways to circumvent sanctions, including through the development of alternative financial mechanisms and the pursuit of closer economic ties with each other and other non-Western partners.

Since the escalation of the war in Ukraine, Russia has increasingly adopted tactics from Iran’s playbook for sanctions evasion in the oil trade. These methods include disabling ship tracking systems, engaging in ship-to-ship transfers in international waters, and using a network of shell companies to obscure the origin of the oil. Despite the economic boycott from the United States and Europe, both countries have remained among the world’s top ten oil producers.

The main beneficiary of discounted Russian and Iranian oil has been China, the world’s largest importer of crude oil and an indispensable strategic partner to both nations. More than 40 percent of Russian oil and as much as 90 percent of Iranian oil is bound for China. Beijing has also consistently diluted or opposed international resolutions against both Moscow and Tehran and supported them with military, cyber, and surveillance technology.

Russia and Iran have also collaborated to build alliances with developing and middle-income nations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America—the so-called Global South—by exploiting their grievances against the current international order and providing them energy, arms, and repressive capacity. In addition to their efforts to buttress global pariahs like North Korea, Belarus, and Syria, Tehran and Moscow have played a critical role in helping preserve the rule of another energy power by providing critical military and financial support: Nicolás Maduro’s government in Venezuela.

This strategic outreach is complemented by their increasing involvement in multilateral organizations that seek to establish a counterbalance to Western dominance on the global stage. Both countries have come to prioritize involvement in multilateral organizations that exclude or minimize Western influence, such as the BRICS+ group of emerging economies, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and the Eurasian Economic Union. In 2022 Iran became a full-blown member of the SCO, and its anticipated inclusion in BRICS+ from 2024 signals its growing importance in this non-Western alliance.

Russia sees Iran as a pivotal state that can serve as a bridge between Central Asia and the Caucasus, the Middle East, and South Asia, enhancing the connectivity and reach of the greater Eurasian project. The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) is a significant geoeconomic initiative championed by Russia and Iran to create a diverse transportation network connecting Eurasia to the Persian Gulf and South Asia. Formalized in 2002 through an agreement between Russia, India, and Iran, the INSTC envisions a complex web of maritime and land routes designed to enhance regional connectivity and trade. Yet a combination of factors—including economic constraints, lack of political will, and international pressures—has stalled the realization of the project.

In their efforts to challenge the U.S.-led global order, Russia and Iran have not only sought to undermine America’s influence abroad but have also actively worked to weaken the United States from within. Both countries are believed to have engaged in actions aimed at exacerbating internal divisions in the United States, mirroring what they perceive as similar tactics used against them. U.S. intelligence agencies have accused these nations of meddling in elections, orchestrating disinformation campaigns, amplifying social unrest, and launching cyber attacks on critical American infrastructure. Furthermore, in response to the detention of their spies and sanctions violators, Moscow and Tehran have increasingly weaponized hostage-taking, detaining U.S. nationals as bargaining chips to secure the release of their own citizens or to extract financial concessions.

Sources of Disagreement

Russia and Iran are inextricably linked by geography, frequently divided by history, and currently united in defiance. Russia has benefited from an Iran isolated from the West, dependent on Russian nuclear technology and weapons sales, hostile to the United States, and unable to exploit its vast energy resources. The Islamic Republic serves these Russian interests. One of Russia’s most frequent commentators on Iran, Rajab Safarov, put it bluntly: “A Western-allied Iran is more dangerous for Russia than a nuclear-armed Iran. . . and would lead to Russia’s collapse.” Khamenei has echoed these views, saying, “The Russians know very well that if a government that supports America had come to power in Iran, what would have happened to them.” Their opposition to the United States and their mutual fight for survival currently binds them, but the future of their partnership cannot be safely predicted beyond the lifespans of their autocratic leaders.

While the war in Ukraine has brought Russia and Iran closer, it has not erased the deep-seated frictions that have long riddled the countries’ ties. At times, this rivalry has spread to the Middle East, where Moscow has maintained ties with many of Iran’s adversaries, even to the detriment of Iran. Though Moscow and Tehran both want to see a diminished U.S. presence in the Middle East, their interests are not identical. While Russia has been increasingly critical of Israel’s war in Gaza, it does not share Tehran’s fierce opposition to Israel’s existence. Before the war in Ukraine, Russia had been accused of looking the other way when Israel bombed Iranian outposts in Syria. Though Russia’s ties to Israel have progressively deteriorated since the war in Ukraine and the Hamas attack of October 7, 2024, the Iranian elite still remain wary of Russia’s ties to Israel. Russia also has trade relations with Israel and with Tehran’s Gulf Arab rivals—including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, whose leaders see Putin as a strategic partner and personal friend.

International sanctions have inadvertently thrust Russia and Iran into direct competition within the shadowy world of illicit oil trade. As legitimate export channels narrow because of sanctions, both countries have been forced to rely increasingly on clandestine markets to sell their oil. Historically, Iran has been a dominant player in markets east of Suez, particularly in China and India. However, Russia's recent entry into these clandestine markets, where it offers discounted prices to attract buyers, has directly challenged Iran's position. This competition threatens Iran's ability to maintain its market share, as Russia's aggressive pricing strategies lure away traditional customers of Iran. The Iranian government has recognized the difficulties posed by Russia’s involvement in the black market as the two nations vie for the same limited opportunities.

Russia and Iran’s common cause has created a bond that transcends their historical rivalries and competing interests. This bond is further strengthened by a shared sense of vulnerability to external interference and potential regime change, fostering a siege mentality that drives their continued cooperation despite underlying tensions. While Russia and Iran have skillfully challenged the U.S.-led global order and circumvented sanctions, their vision for an alternative world order is characterized by a selective application of sovereignty, human rights abuses, and economic instability. This model may attract other autocrats seeking to consolidate power, but it offers little to their own populations, who bear the brunt of repression and financial distress. Ultimately, their approach fosters a world defined more by division and conflict than by the equitable multipolarity they claim to champion.

The relationship was not born through a deliberate strategy or a pure alignment of interests, but as a defensive mechanism against what both regimes perceived as existential threats to their survival. Unlike alliances rooted in shared values and mutual interests, the partnership between theocratic Iran and anti-Islamist Russia is defined by their contrasting values and often conflicting national interests. For the foreseeable future their relationship is held together by the strongest bond of all: a shared enemy.