As the world continues to develop economically, driven by both industrialization and technological advancement, its need for power is increasing, too. In all of history, no country has advanced economically without access to affordable, reliable, and secure energy. Robust energy is the foundation of economic strength, which in turn undergirds national security through resources and innovation. Global energy consumption continues to grow vigorously, especially as the BRICS+ countries’ (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and new members Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates) thirst for energy to fuel their growing economies remains unabated.

World Power Needs Have Only Ever Increased (and Aren’t Going to Stop Now)

In 2023, global energy consumption increased 2.2 percent, a significantly faster rate than its average of 1.5 percent per year in the decade of 2010–2019.1 The BRICS+ countries were a large part of that change, growing at double the average rate (5.1 percent); they represented a full 42 percent of global energy consumption. In more developed Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, with slower GDP growth and diminished industrial production, consumption declined for the second year in a row (although U.S. demand has been flat).2

However, with the increasing importance of energy-intensive artificial intelligence (AI) as a productivity-enhancing game-changer, the power needs of the developed world, particularly the United States given its lead in the AI field, will likely grow—perhaps exponentially. Goldman Sachs forecasts a 15 percent growth rate for data centers (which includes AI) and that they will increase from 3 percent of total U.S. power consumption in 2022 to 8 percent by 2030.3 Other new-tech industries such as electric vehicles (EVs) will also contribute to increased demands on the grid. One tech leader, Bill Gates, clearly believes that increasing energy needs will increase the importance of baseload power; he has invested $1 billion of his own money in advanced nuclear energy (and raised nearly the same amount) via the firm TerraPower in hopes of making nuclear energy more abundant and less expensive.4

In fact, tech companies are starting to contract directly with power stations for their energy needs. For example, Amazon recently bought a nuclear-powered data center in Pennsylvania, and is also trying to close on a deal with Constellation Energy to buy energy directly from one of its nuclear plants.5 Amazon has also signed a deal with Dominion Energy to develop a small modular reactor (SMR) in Virginia.6 Google reached a 2024 deal with California-based Kairos Power to build a series of SMRs to help power its burgeoning AI needs. Supply and demand are of course playing a role.7 With U.S. plant retirements and demand increasing, prices are expected to surge, especially for reliable power. 8

So as discussion continues in the West about an energy transition, it is worth remembering that the world simply needs more energy—whether clean or traditional—even with improved energy efficiency. The point was made a decade ago by former U.S. president Barack Obama’s administration, which noted that the United States needed an “aggressive All-of-the-Above strategy on energy” in order to “build on . . . progress, to foster economic growth, and to protect the planet for future generations.”9

One clean source that is getting increasing attention is nuclear energy, whether produced by fission now or fusion in the future. Nuclear produces power while emitting essentially zero greenhouse gases, similar to solar, wind, and hydroelectric energy. Nuclear is already a clean energy workhorse in the United States, generating about half of U.S. carbon-free energy while operating without intermittency—instead of being at the whim of nature like renewables.10 It is also a safe and proven technology, with newer versions of advanced nuclear (SMRs and micro-reactors) continuing to show promise.

Dependence on Adversaries and the Importance of the Other Low-Carbon Power Source: Nuclear

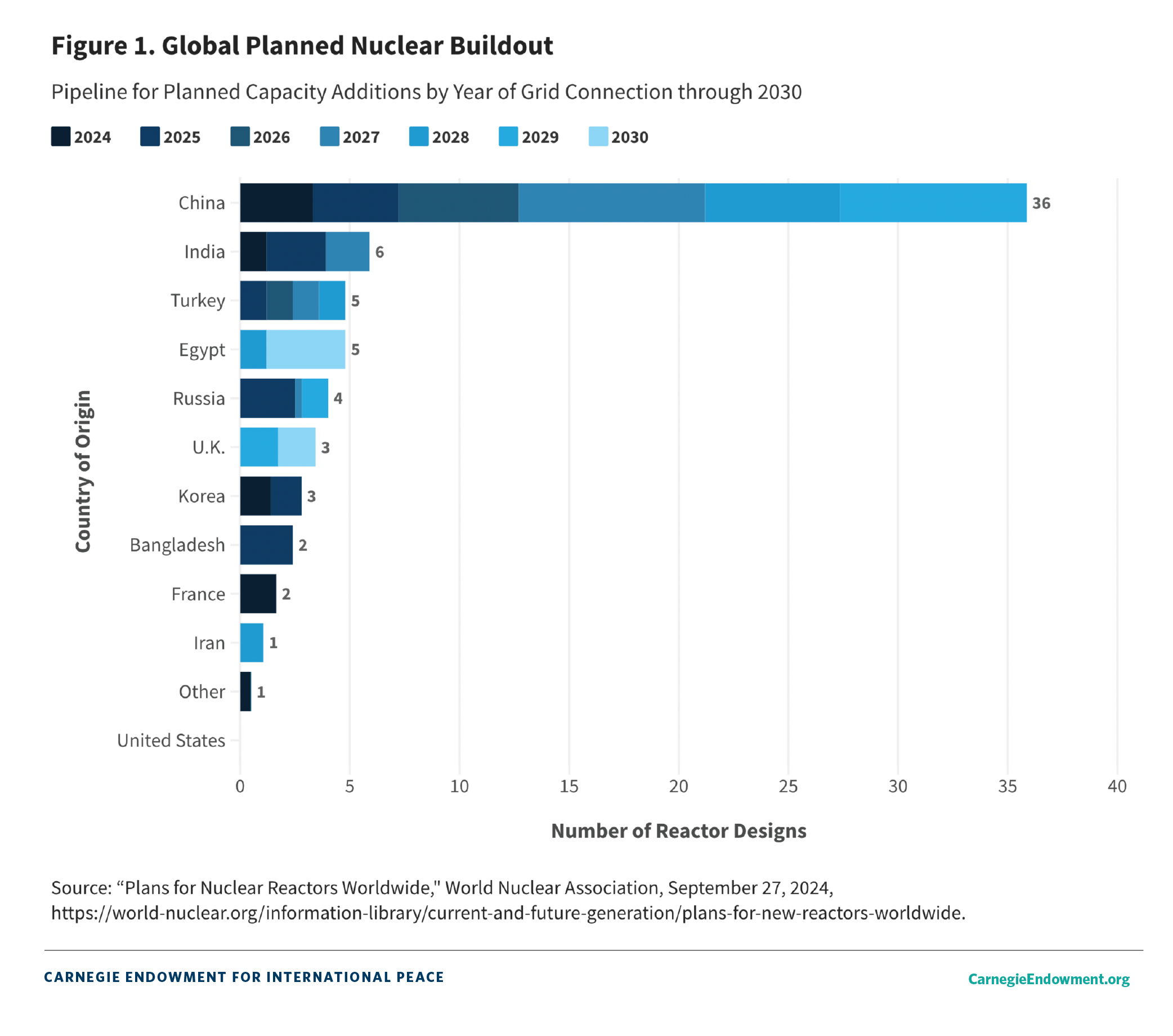

China dominates global supply chains for renewable energy and batteries and is now setting its sights on becoming a superpower in nuclear energy.11 China understands the simultaneous need for clean baseload power in the form of nuclear (despite China’s current heavy reliance on coal) in addition to intermittent renewable energies. Over the past several decades, as the West has grown increasingly cautious about nuclear, China has forged ahead and is now building twenty-five reactors, more than the next six countries combined.12 In fact, it has more nuclear reactors under construction than any other nation in the world, and approved ten new reactors in each of the past two years.13 The country is expected to surpass France and the United States to become the world’s leading atomic power generator by 2030, according to BloombergNEF.14 It also is responsible for a new breakthrough: a meltdown-proof nuclear reactor, which has been a goal for several U.S. companies like X-energy and Kairos, as well as the U.S. Department of Defense, but which China is building faster.15

China’s new nuclear dominance would be added to its control of solar, wind, and EVs (through the magnetic motor and lithium-ion battery supply chain).16 It already processes 90 percent of rare earth elements and 60 to 70 percent of lithium and cobalt (which China manufactures with very low environmental and labor standards).17 Overall, the United States is reliant on other countries for its critical minerals, needing to import more than half its supply of thirty-one out of the thirty-five minerals defined as critical by the government in 2018; the country also has no domestic production at all for fourteen of those minerals.18

The United States must double-track its energy efforts just as China has: work to increase nuclear power as a workhorse that can ensure the United States has reliable electricity, while also (re)establishing domestic renewable supply chains and manufacturing. In other words, America needs to build—and lead—in multiple forms of energy. Unfortunately, it seems the United States cannot get out of its own way.

According to a 2022 International Energy Agency (IEA) analysis that describes the path to reach net zero by 2050, the world would need to double its nuclear energy capacity even with the assumed exponential growth in solar and wind.19 The IEA’s model assumes an average of 30 gigawatts of new nuclear capacity coming online every year starting in the 2030s and staying on that track for another two decades, until 2050. The math then becomes clear: the world needs to build and turn on the equivalent of 180 more 1,000-megawatt reactors, or twenty-five more new reactors per year, by 2030, with further growth afterward in order to hit the 2050 target.20

If all of those reactors are built by China and Russia, not just for their domestic use but also for export, other countries will be locked into their tech and supply chains for decades. Russia supplies more than 40 percent of the world’s enriched uranium, including about 20 percent of what the United States uses, which means one in twenty American households were powered by Russian-enriched nuclear fuel in 2022.21 Fortunately, lawmakers passed the Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act, signed by President Joe Biden in May 2024, which bans unirradiated low-enriched uranium from Russia or Russian firms from being imported into the United States, with the goal of increasing U.S. production.22 The law includes nearly $3 billion in federal funding to expand the domestic uranium industry in hopes of building demand, and will also help build new low-enriched uranium supply (which is what current reactors use as fuel) as well as create capacity to produce high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU, which is what advanced and next-generation reactors use as fuel). Adding Russia and China together, these two U.S. adversaries control nearly 60 percent of the world’s supply of enrichment needed to fuel the next generation of reactors.23

China also intends to build a total of 150 new nuclear reactors between 2020 and 2035, which includes a target of selling thirty nuclear reactors via its Belt and Road Initiative to states it considers its vassals.24 And thanks to its massive state support system, China can build a lot cheaper: it has already bid to build Saudi Arabia’s first nuclear plant at a price at least 20 percent lower than competing bidders.25

China now seems to be at least a decade ahead of the United States in nuclear power, specifically because of its ability to field fourth-generation reactors; is poised to build six to eight new nuclear power plants each year; and is expected to surpass the United States in nuclear-generated electricity by 2030.26 China is expected to finish its first commercially operating SMR by 2026, while leading U.S. advanced nuclear firm TerraPower is expected to be online by 2030.27

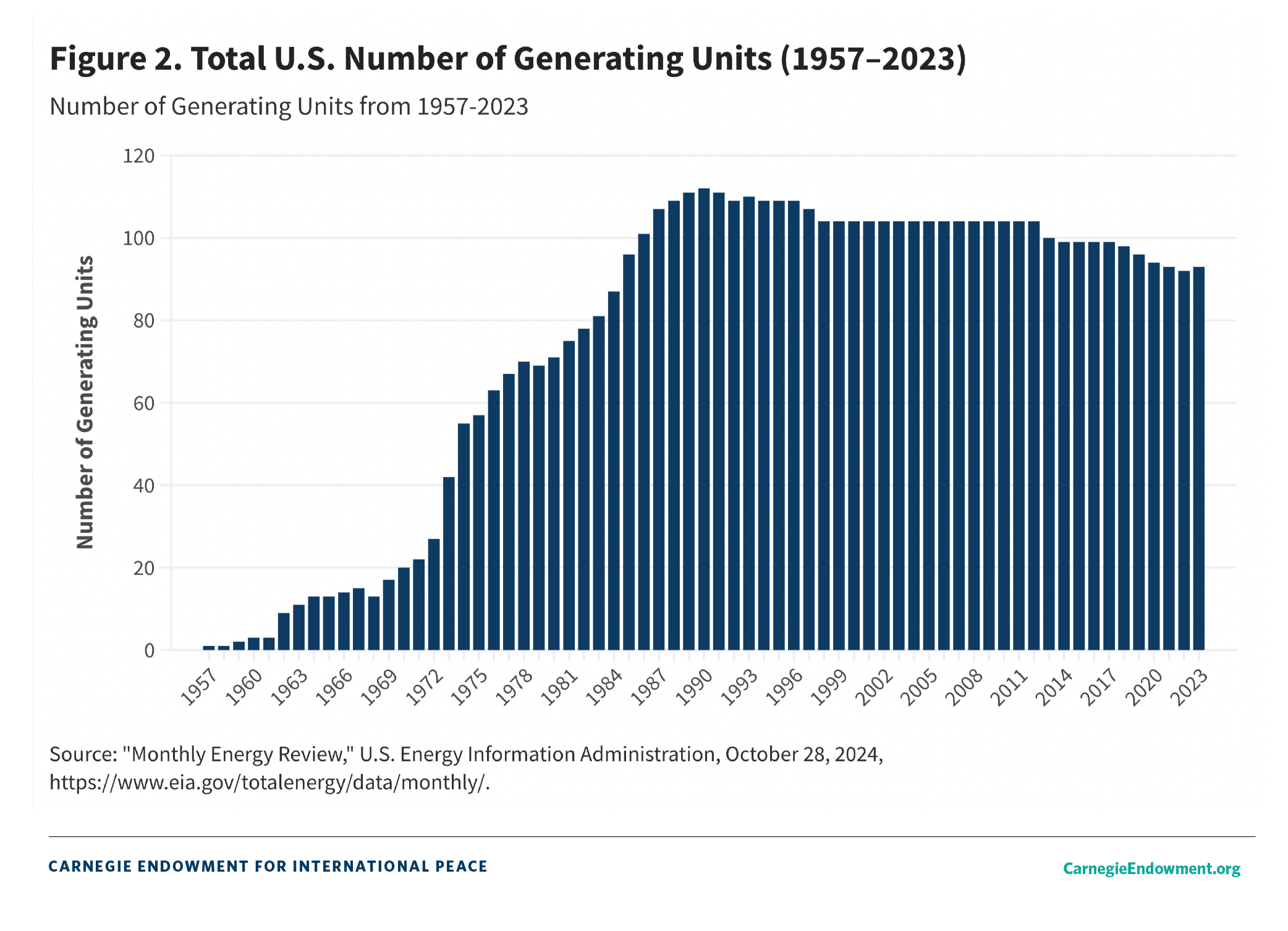

In addition, the current U.S. nuclear fleet is aging. The vast majority of American nuclear capacity was built between 1970 and 1990, with the country’s newest plant (Plant Vogtle’s AP1000 reactor in Georgia) completed in 2024.28 The United States should not wait decades to commission its next nuclear power plant; it is down from its peak of 112 reactors in 1990 to ninety-four operating today.29 Moreover, now is the time to double down on U.S. nuclear development and leverage a domestic workforce that has recently absorbed the know-how of nuclear reactor construction from Vogtle—what economists call diffusion of knowledge, which is essential for economic dynamism and innovation.30 The longer the United States waits to construct a reactor, the more it risks a brain drain of the first batch of expertise gained in decades: some 14,000 workers (including engineers, welders, masons, electricians, mechanics, and support staff) helped to construct the Vogtle plant and could be deployed to build another AP1000 as quickly as possible to keep domestic know-how alive and to maintain nuclear power momentum.31

Meanwhile, China is taking the same approach with nuclear that it took with other forms of green energy: establish and subsidize domestic capacity as a foundation for competitive reactor exports. Beijing’s “dual circulation” strategy to keep its economy from being reliant on imports, particularly from the West, was even enshrined in its constitution.32 It has successfully created Chinese dominance in mineral processing and overcapacity in clean tech, which are killing many domestic producers, not just those in the United States.33 China also got a great deal of help from the United States: one of the main U.S. nuclear firms, Westinghouse, agreed to license its tech to China over several years, even agreeing to allow China to export its technology—which seems like unwise policy in retrospect.34 Beyond that voluntary tech transfer, China’s military also hacked Westinghouse and stole its “confidential and proprietary technical and design specifications for pipes, pipe supports, and pipe routing within the AP1000 plant buildings,” as well as sensitive emails, according to the U.S. Department of Justice indictment.35 (Russia has also been charged with hacking Westinghouse in an effort to steal the company’s IP.)36

If the United States aims to avoid falling behind China on nuclear power, it will have to make producing energy within its own borders easier. That starts with making it easier to mine and build.

The Need for Permitting and Other Reforms to Enhance U.S. Energy Supplies

It’s time to get moving. The United States must accelerate project timelines and streamline processes so developers can get more certainty from regulatory agencies at all levels (federal, state, and local). Costs would come down with increased system efficiency, which would make projects more viable financially from the get-go, and those savings could be passed on to consumers. Permitting reform would also improve investor confidence, particularly in newer, riskier technologies. And of course, permitting reform would allow the United States to be less dependent on foreign sources of energy such as China, which has shown that it is willing to use its economic dominance to punish countries that stand up against it. For example, after Australia called for an international investigation of the origins of COVID-19 in 2020, China banned imports of Australian coal for two years, as well as placing high tariffs on Australia’s agricultural exports.37 China has been able to exert major economic influence thanks to its policy of creating state-owned enterprises that are given various subsidies, tax, and labor advantages, allowing them to dominate global strategic sectors—known as brute force economics.38 It would be a mistake for the United States, which reached full energy independence in 2019, to trade dependence on the Middle East’s oil fields for dependence on China’s energy supply chain.39

On the nuclear side of the energy ledger, the Accelerating Deployment of Versatile Advanced Nuclear for Clean Energy (ADVANCE) Act, signed into law in July 2024, is a sign of progress toward making it easier to produce energy in the United States.40 The law will help push forward more advanced nuclear projects by improving the regulatory regime, lowering licensing fees (with special incentives for next-generation SMRs), and giving the Nuclear Regulatory Commission more flexibility; it also strengthens international coordination.41

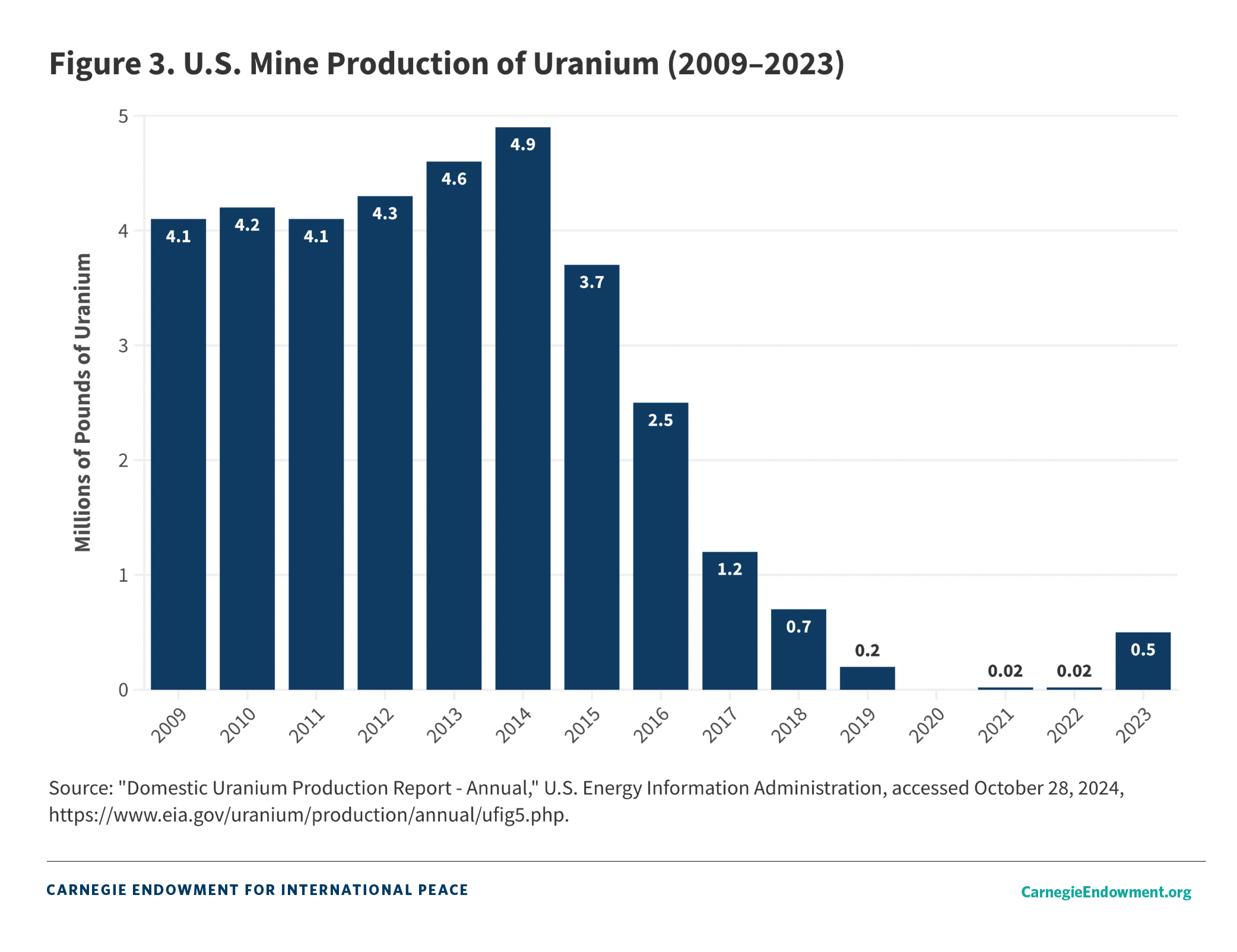

The United States needs to mine its own uranium for its nuclear plants, for which it also needs permitting reform. The country has 48,000 metric tons of identified recoverable uranium resources, yet only mined 6 tons, or 0.1 percent, in 2020.42 The United States has successfully mined uranium in the past—as recently as 2014, when U.S. production was 319 times higher at 1,919 metric tons.43 While the new ban on Russian uranium imports will help, the United States also gets one-quarter of its uranium from Kazakhstan, making it the second-largest source of supply to the United States after Canada.44 Recently, Kazakhstani company Kazatomprom, the world’s largest uranium producer, announced a 17 percent production cut, potentially signaling a closer alliance between Russia and Kazakhstan.45 Amending the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and minimizing red-tape bureaucracy would be a boon for the United States in developing these resources at home, especially the enriched HALEU fuels needed for SMRs, which today are only produced by Russia’s state-owned nuclear firm, Rosatom.

But as policymakers understand, the United States needs permitting reform for more than just nuclear. Last year, many competing permitting reform bills were introduced, starting with HR 1 (whose importance to House of Representatives leadership is indicated by its being given the first bill number), the Lower Energy Costs Act.46 The bill passed in the House with bipartisan support (and some portions of it were included in the debt ceiling deal codified in the Fiscal Responsibility Act) but languished in the Senate.47 In July 2024, the bipartisan Energy Permitting Reform Act of 2024 was introduced, aiming to speed up energy permitting to meet increasing demand.48 The bill targets permitting problems affecting renewables, natural gas, critical minerals, hydropower, geothermal, and federal permitting, and also deals with infrastructure issues like the grid and pipelines to ensure power generation can be distributed. U.S. natural gas entails lower emissions than that of many competitors, and many U.S. allies now depend more on U.S. liquified natural gas (LNG) exports in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.49

Permitting reform should be bipartisan. In late July 2024, the bill passed out of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on a fifteen-to-four vote, which bodes well for its future in either the lame duck session at the end of 2024 or the new Congress in 2025.

So if the United States is intent on manufacturing batteries domestically, permitting reform is imperative to allow access to domestic resources (especially since China has taken so much of the rest of the world off the table). Permitting reform would also benefit another key baseload energy form: natural gas, which the United States produces more cleanly than other suppliers. For example, emissions from Russian-supplied LNG can be nearly four times as high as those from U.S. LNG.50

Thus, U.S. LNG means exports of cleaner gas, especially to allies with gaps in their gas supplies left by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (not to mention some European countries’ overdependence on Russia for said gas, which made them economically vulnerable to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s whims). Geopolitically, U.S. LNG exports have never been more important, and the country needs to assure allies that its supply is solid, as opposed to being cut off by the Biden administration’s LNG “pause” (which has been overturned by the courts) or by the court system in response to activist lawsuits.51

The Global South Has Energy Needs, Too

Beyond the domestic landscape, the United States and its allies also need to be more proactive in the international energy space, helping countries develop economically while also furthering U.S. exports of clean energy, particularly to the Global South, to counter Chinese and Russian financing offers that lock countries into using their technology. Right now, the United States seems to have essentially abdicated the nuclear playing field, mainly to its adversaries.

Nuclear is of course capital- and time-intensive to start up, which is why financing is key. Although the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) lifted its nuclear financing ban in 2020, four years later it has yet to give any nuclear loans.52 However, it has signed letters of intent with several American firms to use U.S. technology.

The Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act, which transformed the Overseas Private Investment Corporation into the DFC, is up for Congressional reauthorization in 2025. In order to better compete with China—a key part of its mission—the DFC needs reform. This could include revisiting how its equity stakes are scored (costs estimated by the government) as well as not shying away from baseload energy. The DFC could also take a more proactive approach toward extractives so the United States can avoid relying on China not just for solar and batteries, but also for the defense and semiconductor mineral supply chain, which are key to economic and national security.

Another source of energy finance for developing countries is the World Bank, which continues to ban loans for nuclear energy, no longer funds any upstream oil and gas projects (since 2019), and stopped funding coal in 2013.53 Other multilateral development banks have followed the World Bank’s lead on most of these issues.54 As a result, developing countries are forced to rely on China for opaque and expensive financing to meet baseload energy needs. Ironically, while China projects its green credentials—with President Xi Jinping issuing bromides like “We must protect this planet like our own eyes, and cherish nature the way we cherish life”—it still accounts for two-thirds of global new coal capacity, which is why its coal-fired power output increased to new highs in 2023 (although it seems to be slowing down its construction of new coal plants, whether that lasts remains to be seen).55 China also emitted 35 percent of the world’s greenhouse gases in 2023—an increase of almost 5 percent over 2022—making it the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter.56 Nevertheless, the World Bank continues to loan over $1 billion per year to China while simultaneously pushing a green agenda. 57 And because money is fungible, it is possible that for every loan the World Bank gives China, China can use that saved money toward another coal plant.

Because of the World Bank’s intransigence on the nuclear issue, in spite of its green goals, there is a proposal to start a new multilateral development bank focused solely on financing nuclear power in the developing world.58 Its proposed members and funders include the nuclear club countries of Canada, France, Japan, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom (thus cutting out China and Russia). The proposed International Bank for Nuclear Infrastructure’s goal would be to help provide financing for projects in developing countries that have expressed interest in nuclear, like Ghana,59 and to make South Korean, American, and European nuclear technology more competitive with Russian and Chinese exports.60 While there is bipartisan support for nuclear in Congress, potential U.S. funding for the bank might depend on how much other allies are willing to contribute and where the bank would be located.

The developing world needs energy finance, but the developed world is focused on limiting Global South sovereigns’ capacity to develop their own natural energy resources such as gas, in spite of the fact that Africa emits less than 4 percent of the world’s greenhouse gases.61 Self-righteously, this policy continued even after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, when many European countries sought to buy Africa’s oil and gas resources, pushing for exports to their own economies even as they actively worked to prevent African countries from using those resources themselves—a contrast African leaders have noticed and that has been termed “green colonialism.”62 In addition, Germany may be forced to keep its coal plants open longer than it had intended because of the intermittency of its renewable energy and because it shut down its nuclear capacity before it had equivalent, reliable substitutes in place.63 It is also pushing for more gas (despite voting against most gas projects at the World Bank for developing countries) to replace its coal use. Germany’s brazenly hypocritical “do as I say, not as I do” approach only helps to expand China’s sphere of influence in the Global South by communicating that the West wants to keep developing countries down by stymieing their economic development, and that only China understands them and their needs.

Conclusion

Wind and solar power are not going to be able to provide the amount of power that energy-intensive AI will need in order to blossom—an estimated 160 percent increase in data-center power in the next six years alone.64 Unlike other tech innovations, where much of the manufacturing could be outsourced overseas (often to the detriment of the United States in the long run), AI’s physical infrastructure must be built in the United States because of economic security concerns. For that reason alone, the country needs an all-of-the-above energy strategy that includes gas, nuclear (if it can scale up), and variable renewable sources (which cannot supply enough power by themselves in any scenario). Interestingly, the Palisades Power Plant in Michigan is set to reopen after shutting down in 2022, making it the first decommissioned nuclear plant to be restarted.65 And even Three Mile Island (infamously the site of a partial meltdown in 1979), which was closed in 2019, may be put back into commission in response to the new power demands from AI.66

So while the United States is un-mothballing old nuclear plants and rarely building new ones, China is leaping ahead, thanks not only to the Chinese government’s financing and subsidies, but also through other supportive policies like streamlined permitting and fast regulatory approval (and stolen U.S. intellectual property). China has been finishing construction on plants in between five and seven years each, while the most recently constructed U.S. plant, Vogtle, took thirty years.67 The United States could learn from China’s example here.

America needs to bring supply chains stateside, including mineral extraction and processing, so that it is not dependent on adversaries for renewables and other sources of power. It must work with foreign partners who have the mineral resources the country needs and consider what their energy needs are, too. And the United States must update its outdated and cumbersome permitting processes and agency coordination for energy projects of all kinds so it can become fully energy-independent again.

The country could also use its geopolitical leverage to seek nuclear trade agreements with countries like Saudi Arabia; currently, the terms the United States has set—requiring the Saudis to forgo rights to develop fuel, which China is reportedly not requiring—are competing the United States out of a deal. The United States needs to lower the cost of nuclear fuel by reforming regulation of nuclear fuel production. If the United States is concerned about allowing partners to enrich their own nuclear fuel, which scholars consider the most significant risk of SMR supply chains with regard to nuclear non-proliferation, then the United States must be able to guarantee fuel to foreign buyers.68

However, there are fail-safes: all U.S. agreements on nuclear energy (known as 123 Agreements—negotiated by the U.S. Department of State with technical assistance from the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission) explicitly require adherence to strong non-proliferation criteria. The United States and its Nuclear Regulatory Commission are widely considered to be the gold standard for nuclear safety around the world. In addition, it is worth noting that nothing prevents China from transferring enrichment technology to Saudi Arabia, so the United States refusing to do so does not guarantee that the Saudis will be unable to acquire the technology. At the end of the day, it would be more beneficial for the United States to keep the Saudis in its own sphere of influence than to push them into the arms of China or Russia.

The United States also could take advantage of its current talent base and expand it, including with better science and technology education, as well as leveraging the country’s unique economic dynamism and creativity through smart regulation to get better and safer products to the market. As it has done in other industries, the United States can outcompete China on quality if investors can confidently invest money in the nuclear technology industry. And finally, the United States could immediately leverage its burgeoning micro-reactor industry, where it has the potential to outpace China.

The path to establishing more independent and sustainable energy is clear, and it will require investment in multiple kinds of power production. Political and economic willpower will be necessary to ensure the United States has the right energy policies in place to secure the rapidly changing new technologies feeding the nation’s economic growth and prosperity.

Notes

1“Total Energy Consumption,” Enerdata World Energy & Climate Statistics, accessed October 23, 2024, https://yearbook.enerdata.net/total-energy/world-consumption-statistics.html.

2Enerdata World Energy & Climate Statistics, “Total Energy Consumption.”

3“AI Is Poised to Drive 160% Increase in Data Center Power Demand,” Goldman Sachs, May 14, 2024, https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/AI-poised-to-drive-160-increase-in-power-demand.

4Brad Plumer, “Nuclear Power Is Hard. A Climate-Minded Billionaire Wants to Make It Easier,” New York Times, June 11, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/11/climate/bill-gates-nuclear-wyoming.html.

5Jennifer Hiller and Sebastian Herrera, “Tech Industry Wants to Lock Up Nuclear Power for AI,” Wall Street Journal, July 1, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/business/energy-oil/tech-industry-wants-to-lock-up-nuclear-power-for-ai-6cb75316.

6Diana Olick, “Amazon Goes Nuclear, to Invest More Than $500 Million to Develop Small Nuclear Reactors,” CNBC, October 16, 2024, https://www.cnbc.com/2024/10/16/amazon-goes-nuclear-investing-more-than-500-million-to-develop-small-module-reactors.html.

7Jennifer Hiller, “Google Backs New Nuclear Power Plants to Power AI,” Wall Street Journal, October 14, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/business/energy-oil/google-nuclear-power-artificial-intelligence-87966624.

8Naureen S. Malik and Mark Chediak, “Record Payouts on Biggest US Grid Signal Costs of Reliable Power,” Bloomberg, July 30, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-07-30/power-plant-payouts-on-biggest-us-grid-to-rise-to-record-in-june.

9“The All-Of-The-Above Energy Strategy as a Path to Sustainable Economic Growth,” White House Council of Economic Advisers, last updated July 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/aota_report_updated_july_2014.pdf.

10“Five Fast Facts About Nuclear Energy,” U.S. Office of Nuclear Energy, June 11, 2024, https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/5-fast-facts-about-nuclear-energy.

11Isabel Hilton, “How China Became the World’s Leader on Renewable Energy,” Yale School of the Environment, March 13, 2024, https://e360.yale.edu/features/china-renewable-energy.

12Amy Ouyang, “A Nuclear Renaissance Around the Corner? (Part I),” Macro Polo, May 16, 2024, https://macropolo.org/analysis/a-nuclear-renaissance-around-the-corner-part-i/.

13 “China Makes $31 Billion Nuclear Push With Record Approvals,” Bloomberg, August 19, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-08-20/china-approves-record-11-new-nuclear-power-reactors.

14Bloomberg, “China Makes $31 Billion Nuclear Push.”

15Stuti Mishra, “China Unveils Meltdown-Proof Nuclear Power Plant in Clean Energy Breakthrough,” Independent, July 26, 2024,

16Jennifer Dlouhy, “China Extends Clean Tech Dominance Over U.S. Depite Biden’s IRA,” Bloomberg, April 16, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2024-04-16/china-extends-clean-tech-dominance-over-us-despite-biden-s-ira-blueprint.

17Michael Standaert, “China Wrestles with the Toxic Aftermath of Rare Earth Mining,” Yale Environment 360, July 2, 2019, https://e360.yale.edu/features/china-wrestles-with-the-toxic-aftermath-of-rare-earth-mining.

18“Critical Mineral Resources: National Policy and Critical Minerals List,” Congressional Research Service, updated April 8, 2024, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47982/3#:~:text=26%20E.O.,the%2035%20listed%20critical%20minerals.

19“Nuclear Power and Secure Energy Transitions,” International Energy Agency, June 2022,

20DJ Nordquist and Jeffrey S. Merrifield, “The World Needs More Nuclear Power,” Foreign Affairs, January 12, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/the-world-needs-more-nuclear-power.

21“Fuel Supply Chain Updates as U.S. and Allies ‘Sever Dependency’ on Russian U,” Nuclear Newswire, April 30, 2024, https://www.ans.org/news/article-5998/fuel-supply-chain-updates-as-us-and-allies-sever-dependency-on-russian-u/; Jennifer T. Gordon, “The US Is Banning the Import of Russian Nuclear Fuel. Here’s Why That Matters,” Atlantic Council, May 16, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-us-is-banning-the-import-of-russian-nuclear-fuel-heres-why-that-matters/; James Krellenstein and Garrett Wilkinson, “Expanding U.S. Uranium Enrichment: Ending Global Dependence on Russian Nuclear Fuel and Paving the Way for Deep Decarbonization,” Global Health Strategies Climate, May 10, 2023, https://globalhealthstrategies.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/GHS-Climate_White-Paper_Expanding-US-Uranium-Enrichment_12-May-2023.pdf.

22“All Information (Except Text) for H.R.1042 - Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act,” Congress.gov, accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/1042/all-info.

23“Re-establishing American Uranium Leadership,” Clearpath, September 27, 2023, https://clearpath.org/our-take/re-establishing-american-uranium-leadership/.

24Dan Murtaugh and Krystal Chia, “China’s Climate Goals Hinge on a $440 Billion Nuclear Buildout,” Bloomberg, November 2, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-11-02/china-climate-goals-hinge-on-440-billion-nuclear-power-plan-to-rival-u-s

25Summer Said, Sha Hua, and Dion Nissenbaum, “Saudi Arabia Eyes Chinese Bid for Nuclear Plant,” Wall Street Journal, August 25, 2023,

26Stephen Ezell, “How Innovative Is China in Nuclear Power?,” Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, June 17, 2024,

27“Core Module Installed at Chinese SMR,” World Nuclear News, August 10, 2023,

Paul Day, “First TerraPower Advanced Reactor on Schedule but Fuel a Concern,” Reuters, May 9, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/first-terrapower-advanced-reactor-schedule-fuel-concern-2024-05-09/.

28Slade Johnson, “Plant Vogtle Unit 4 Begins Commercial Operation,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, May 1, 2024, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=61963.

29“How Many Nuclear Power Plants Are in The United States, and Where Are They Located?,” U.S. Energy Information Agency, updated May 8, 2024, https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=207&t=3.

30Ufuk Akcigit, Sina T. Ates, and Craig A. Chikis, “Trends in U.S. Business Dynamism and the Innovation Landscape,” Economic Innovation Group, September 20, 2023. https://eig.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Trends-in-U.S.-Business-Dynamism-and-the-Innovation-Landscape.pdf.

31“Vogtle Electric Generating Plant,” Southern Company, accessed October 24, 2024, https://assets.gpb.org/files/pdfs/georgiagazette/Plant_Vogtle_Brochure.pdf.

32Hung Tran, “Dual Circulation in China: A Progress Report,” Atlantic Council, October 24, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/dual-circulation-in-china-a-progress-report/.

33“Clean Energy Supply Chains Vulnerabilities,” International Energy Agency, 2023, https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-technology-perspectives-2023/clean-energy-supply-chains-vulnerabilities.

34“U.S.-China Nuclear Cooperation Agreement,” Congressional Research Service, updated August 18, 2015, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33192/26.

35Jose Pagliery, “What Were China’s Hacker Spies After?” CNN, May 19, 2014, https://money.cnn.com/2014/05/19/technology/security/china-hackers; “U.S. Charges Five Chinese Military Hackers for Cyber Espionage Against U.S. Corporations and a Labor Organization for Commercial Advantage,” U.S. Department of Justice, May 19, 2014, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-charges-five-chinese-military-hackers-cyber-espionage-against-us-corporations-and-labor.

36Sarah N. Lynch, Lisa Lambert, and Christopher Bing, “U.S. Indicts Russians in Hacking of Nuclear Company Westinghouse,” Reuters, October 4, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/u-s-indicts-russians-in-hacking-of-nuclear-company-westinghouse-idUSKCN1ME1TL/.

37Georgia Edmonstone, “China’s Trade Restrictions on Australian Exports,” United States Study Centre, April 2, 2024, https://www.ussc.edu.au/chinas-trade-restrictions-on-australian-exports.

38Liza Tobin, “China’s Brute Force Economics: Waking Up from the Dream of a Level Playing Field,” Texas National Security Review 6, no.1 (2022/2023), https://tnsr.org/2022/12/chinas-brute-force-economics-waking-up-from-the-dream-of-a-level-playing-field/.

39“US Energy Facts Explained,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, updated July 15, 2024, https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/imports-and-exports.php.

40“SIGNED: Bipartisan ADVANCE Act to Boost Nuclear Energy Now Law,” U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, July 9, 2024, https://www.epw.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2024/7/signed-bipartisan-advance-act-to-boost-nuclear-energy-now-law.

41Abbie Bennett and Zack Hale, “Biden Signs Bill to Boost Advanced Nuclear Development,” S&P Global, July 10, 2024, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/071024-biden-signs-bill-to-boost-advanced-nuclear-development.

42Matt Bowen and Paul Dabbar, “Reducing Russian Involvement in Western Nuclear Power Markets,” Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy, May 2022, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/RussiaNuclearMarkets_CGEP_Commentary_051822-2.pdf.

43“World Uranium Mining Production,” World Nuclear Association, May 16, 2024,

44“Nuclear Explained,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, last updated August 23, 2023, https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/nuclear/where-our-uranium-comes-from.php.

45 Harry Dempsey, “World’s largest uranium producer slashes production target,” Financial Times, August 23, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/240af090-8684-49dc-a85e-20b535d62dda.

46“H.R. 1, The Lower Energy Cost Act,” U.S. House of Representatives, March 14, 2023, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-118hr1ih/xml/BILLS-118hr1ih.xml.

47“H.R.3746 - Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023,” U.S. House of Representatives, Congress.gov, accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/3746.

48S.4753 - Energy Permitting Reform Act of 2024, Congress.gov, accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/4753.

49Sasha Bylsma et al., “Which Gas Will Europe Import Now? The Choice Matters to the Climate,” RMI, March 16, 2022. https://rmi.org/which-gas-will-europe-import-now-the-choice-matters-to-the-climate/; Samanatha Gross and Constanze Stelzenmuller, “Europe’s Messy Russian gas divorce,” Brookings Institution, June 18, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/europes-messy-russian-gas-divorce/.

50Selina Roman-White et al., “Cycle Greenhouse Gas Perspective on Exporting Liquified National Gas from the United States: 2019 Update,” National Energy Technology Laboratory, September 12, 2019,

51“FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Temporary Pause on Pending Approvals of Liquefied Natural Gas Exports,” White House, January 26, 2024,

Maxine Joselow, “Federal Court Blocks Biden’s Pause on Approving Gas Export Projects,” Washington Post, July 1, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2024/07/01/liquefied-natural-gas-exports-court-ruling/.

Alexandra E. Ward et al., “Court Strikes Down Key Endangered Species Act Opinion,” Holland and Knight, August 29, 2024,

52“Report on DFC’s Financing Nuclear Energy-Related Projects Overseas,” U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, March 2024, https://www.dfc.gov/sites/default/files/media/documents/DFC%20Report%20-%20Civilian%20Nuclear%20Energy%202024.pdf.

53“World Bank Group Announcements at One Planet Summit,” World Bank, December 12, 2017, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2017/12/12/world-bank-group-announcements-at-one-planet-summit; Brad Plumer, “The World Bank Cuts Off Funding for Coal. How Big an Impact Will That Have?,” Washington Post, July 17, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2013/07/17/the-world-bank-cuts-off-funding-for-coal-how-much-impact-will-that-have/.

54“IAEA DG Grossi to World Bank: Global Consensus Calls for Nuclear Expansion, This Needs Financial Support,” International Atomic Energy Agency, June 24, 2024, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/iaea-dg-grossi-to-world-bank-global-consensus-calls-for-nuclear-expansion-this-needs-financial-support.

55“Xi Promotes Global Efforts Towards Building a Shared Future for All Life,” China Central Television, May 22, 2023, https://english.cctv.com/2022/05/23/ARTIlI70Xuk99HTtika20nuy220523.shtml.; Dylan Butts, “China Accounted for Two-Thirds of New Global Coal Plant Capacity in 2023, Report Finds,” CNBC, April 14, 2024, https://www.cnbc.com/2024/04/15/china-boosts-global-coal-power.html.

Gavin Maguire, “China's Power Sector Emissions to Surpass 4 Billion Metric Tons in 2023,” Reuters, December 21, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/chinas-power-sector-emissions-surpass-4-billion-metric-tons-2023-2023-12-21/.

Ken Moritsugu, “China Is Backing Off Coal Power Plant Approvals After a 2022-23 Surge That Alarmed Climate Experts,” Associated Press, August 20, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/china-coal-plant-approval-permit-greenpeace-72f2c457e3ee6f09aef464a017acae2d.

56“Energy-Intensive Economic Growth, Compounded by Unfavourable Weather, Pushed Emissions Up in China and India,” International Energy Agency, accessed October 28, 2024, https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2023/energy-intensive-economic-growth-compounded-by-unfavourable-weather-pushed-emissions-up-in-china-and-india; “CO2 Emissions in 2023,” International Energy Agency, accessed October 28, 2024,

57“IBRD/IDA Summary,” World Bank, September 30, 2024, https://financesapp.worldbank.org/summaries/ibrd-ida/#ibrd-len/countries=CN/.

58“A Nuclear Bank for Scaling and Risk Mitigation,” Nuclear Engineering International, September 6, 2023, https://www.neimagazine.com/advanced-reactorsfusion/a-nuclear-bank-for-scaling-and-risk-mitigation-11126373/?cf-view.

59“Nuclear Financing – Creation of IBNI is critical for Global Nuclear Scaling and 2050 Net Zero,” International Atomic Energy Agency, December 9, 2023,

60Alexander Kaufman, “Inside The Ambitious Plan To Compete With Russia On Nuclear Energy Again,” Huffington Post, August 17, 2024, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/global-nuclear-bank_n_66a7ee9fe4b0e33a3bb7a8e1.

61Saifaddin Galal, “Africa's Share in Global Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions From 2000 to 2021,” Statista, November 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1287508/africa-share-in-global-co2-emissions/.

62Andreas Rinke et al., “Energy-Hungry Germany's Scholz Courts Africa as Crises Elsewhere Bite,” Reuters, October 27, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/energy-hungry-germanys-scholz-courts-africa-crises-elsewhere-bite-2023-10-27/; Neil Munshi, Paul Burkhardt, and William Clowes, “Europe’s Rush to Buy Africa’s Natural Gas Draws Cries of Hypocrisy,” Bloomberg, July 10, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-07-10/europe-s-africa-gas-imports-risk-climate-goals-leave-millions-without-power?; Vijaya Ramachandran, “Rich Countries’ Climate Policies Are Colonialism in Green,” Foreign Policy, November 3, 2021,

63Petra Sorge, “Germany Set to Pay More Coal Plants to Prevent Blackouts,” Bloomberg, April 30, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-04-30/germany-set-to-pay-more-coal-plants-to-prevent-blackouts.

64Goldman Sachs, “AI Is Poised To Drive 160% Increase.”

65Eric Niiler, “Can a Closed Nuclear Power Plant From the ’70s Be Brought Back to Life?” Wall Street Journal, August 26, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/business/energy-oil/biden-nuclear-power-plant-loan-michigan-eee64904.

66“Backgrounder on the Three Mile Island Accident,” U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, updated March 28, 2024, https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/3mile-isle.html; Evan Halper, “A Nuclear Accident Made Three Mile Island Infamous. AI’s Needs May Revive It,” Washington Post, July 10, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2024/07/10/three-mile-island-nuclear-artificial-intelligence/.

67“Vogtle Fun Facts,” Georgia Power, accessed October 24, 2024, https://www.georgiapower.com/company/plant-vogtle/vogtle-facts.html.

68Philseo Kim and Sunil S. Chirayath, “Assessing the Nuclear Weapons Proliferation Risks in Nuclear Energy Newcomer Countries: The Case of Small Modular Reactors,” Nuclear Engineering and Technology 56, no. 8 (August 2024), 3155–3166, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1738573324001347?via%3Dihub.

.jpg)