On October 1, Iran attacked Israeli territory directly for the second time this year. The barrage of approximately 180 ballistic missiles followed a series of Israeli assassinations, sabotage operations, and military incursions, which have degraded proxies like Hamas and Hezbollah that play a key role in Iran’s defense strategy. Although Tehran likely hoped this strike would end the cycle of escalation, according to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Iran made “a big mistake . . . and it will pay for it.” Precisely how remains unclear, but the temptation for Iran to consider more drastic options to reset regional dynamics will only grow if these patterns of action and reaction continue.

One possibility is that Iran could make good on its periodic threat to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and curtail cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the watchdog organization tasked with verifying that Iran’s nuclear program remains exclusively peaceful. Article X of the treaty allows for this, requiring a state to give three months’ notice and explain the “extraordinary events” that have jeopardized “its supreme national interests.” Presumably Iran would cite Israel’s refusal to join the NPT; its military activities in the region, including against Iranian targets; as well as sustained international pressure.

Withdrawing from the NPT would not necessarily mean that Iran had decided to proliferate, but it would amplify speculation. Although Tehran has long insisted that it does not want to acquire nuclear weapons, it could build them relatively quickly if it chose to do so. Since former U.S. president Donald Trump’s administration pulled out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018, Iran has further advanced its nuclear capabilities and rolled back the deal’s extensive monitoring and verification commitments, diluting the international community’s ability to rapidly detect proliferation. While ending oversight would be a significant escalation, Iran’s nuclear program is already trending in a dangerous direction, which might lead policymakers to inflate the benefits of opacity and underestimate the consequences.

The most obvious reason for any country to terminate IAEA oversight would be to hide bomb-making capabilities. But reducing transparency might also be seen as leverage, allowing a state to barter access for sanctions relief. Alternatively, leaders could make such decisions in response to perceived infringements upon their sovereign rights, or simply to save face. Even if Iran does not cross the proliferation threshold, policymakers in Tehran might believe that stoking ambiguity around their nuclear program would add gravity to their threats at a moment in which their regional position is imperiled. Iran’s waning faith in meaningful sanctions relief and deepening relationship with Russia might also convince the regime that it would have little to lose from a more categorical break.

History, however, suggests that playing political football with international oversight rarely ends well for anyone. Revisiting Iraq’s 1998 decision to stop cooperating with international weapons inspectors is a sobering reminder that if Iran goes down this route, the most likely outcome is a toxic cocktail of uncertainty and worst-case thinking that will increase the risks of miscalculation and undercut the feasibility of conflict off-ramps.

If Iran is dead set on building a nuclear arsenal, it will have to accept these costs. But if Tehran wants to mitigate the risks of a conflict that could prove catastrophic for the country—let alone preserve space for President Masoud Pezeshkian’s declared interest in reopening nuclear negotiations—then addressing metastasizing uncertainties about its nuclear program rather than intensifying them would be to its benefit. Transparency is no panacea, but it provides a check on dangerous speculation.

Inspecting the Uninspected and the Road to War in Iraq

At the most basic level, international monitoring and verification regimes seek to dissuade illicit nuclear activities by increasing the probability that they will be detected in a timely manner and trigger punitive international responses. The central organ of the nuclear order is the IAEA, which carries out the twin tasks of helping countries develop civilian nuclear applications and safeguarding those programs to ensure they remain exclusively peaceful. While no verification regime is foolproof, routine inspections and monitoring tools enhance transparency and improve the chances that the international community will identify strategically salient violations early enough to devise meaningful policies. The presence of inspectors and monitoring equipment also informs national leaders’ decisionmaking, by shaping what they think they can and cannot get away with.

Iran has a history of fluctuating cooperation with the IAEA, but it has never cut off engagement. Indeed, while the nuclear age is littered with cases of noncompliance, only two states—Iraq and North Korea—have effectively expelled international inspectors. The case of Iraq is particularly interesting because Saddam Hussein’s resistance to, and ultimate rejection of, international weapons inspections bolstered U.S. suspicions of illicit weapons of mass destruction (WMD) (which ultimately proved ungrounded) and fed into the George W. Bush administration’s justification for invading in 2003. This episode highlights some of the risks of nuclear ambiguity that all parties should consider before initiating processes that are hard to reverse.

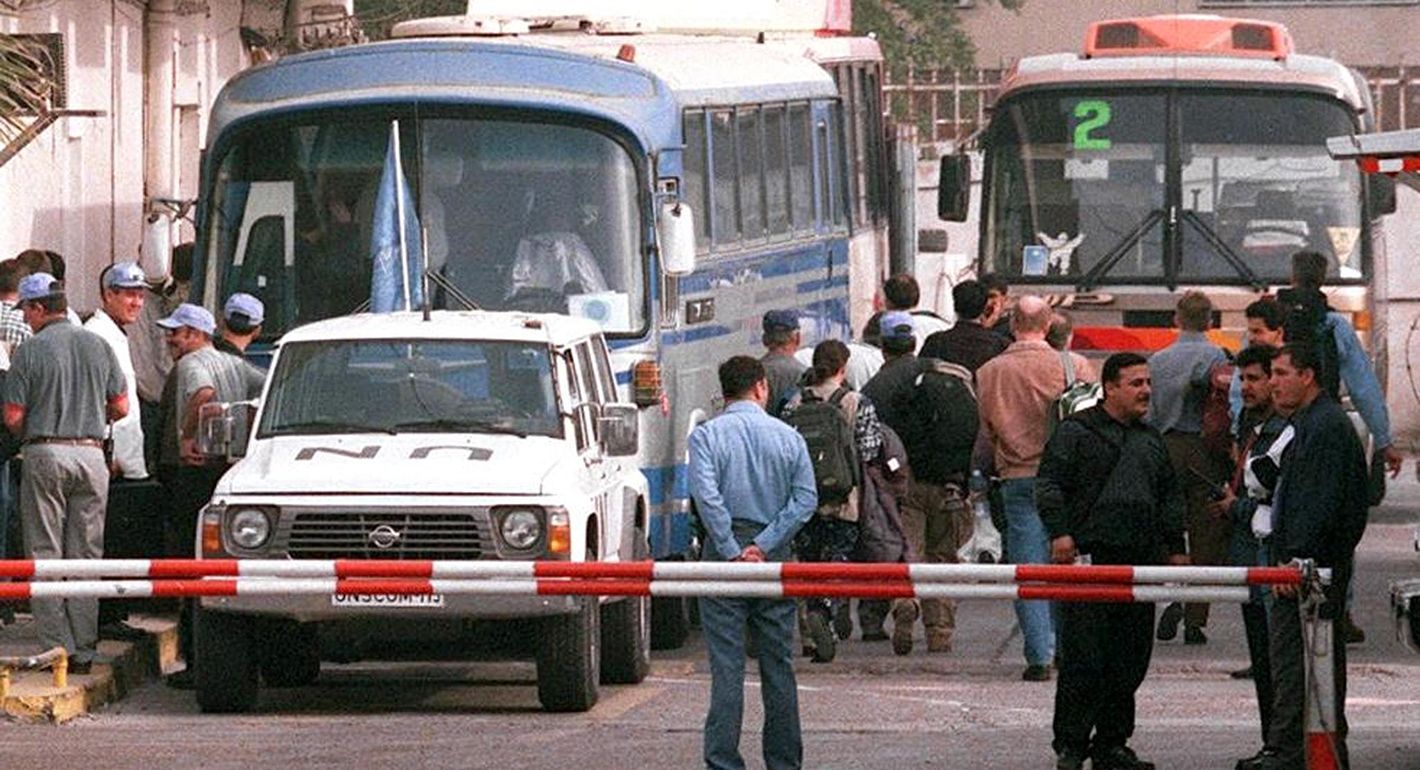

Iraq spent almost two decades trying to build the bomb, starting in the 1970s. In 1981, Israel temporarily set these efforts back by destroying the reactor that Baghdad planned to use as a source of weapons-grade plutonium; however, the regime covertly reconstituted its program, pursuing other pathways to produce fissile material and conducting research on weapons-design and delivery systems. The full scope of these activities only became apparent following Iraq’s defeat in the Gulf War in 1991. After the war, the UN Security Council ordered Baghdad to dismantle its WMD programs under the supervision of inspectors from the IAEA and the UN. While Iraq had to accept these terms, cooperation was fickle, and the regime often obstructed inspectors’ work by providing false or incomplete information, tampering with evidence, and denying site access. In a particularly dramatic moment, UN officials seized documents related to Iraq’s nuclear program, precipitating an armed, four-day-long standoff in an Iraqi parking lot, which the international news media covered live.

Despite these spectacular bouts of intransigence, inspectors dismantled the bulk of the Iraqi nuclear weapons infrastructure by the late 1990s, and gained significant insight into the program. Still, Saddam chafed against the humiliation of forceable disarmament and the sanctions that the international community continued to impose. In 1998, although the Iraqi weapons program was effectively neutralized, Iraq announced that it would stop cooperating with inspections. After several fruitless rounds of diplomacy, the United States and the UK opted for a military response and evacuated IAEA and UN inspections teams. Iraq refused to readmit them or to comply with its disarmament obligations.

Undermining inspections was a crucial blunder for Saddam. These decisions did not translate into greater leverage or prestige; instead, they were misread, and Iraq’s track record of deceit and resistance colored subsequent assessments of its motivations and capabilities. As Bush put it in his 2002 “Axis of Evil” speech, “This is a regime that agreed to international inspections—then kicked out the inspectors. This is a regime that has something to hide from the civilized world.” Steve Coll’s recent book shows that misunderstandings cut both ways. Saddam (erroneously) assumed that the United States knew that Iraq no longer had a viable nuclear weapons program, with or without inspectors on the ground, and thus believed Washington’s WMD charges were a pretense to force him from power.

Concerns about Iraq’s nuclear program were not solely responsible for the war, and many U.S. policymakers discounted countervailing information or massaged dubious intelligence to justify their desire for regime change. That said, Saddam’s repudiation of international oversight rendered contestable arguments and interpretations more credible. Compounding miscalculations also thwarted efforts to diffuse the crises they spawned. Baghdad readmitted weapons inspectors in 2002, hoping to forestall the looming U.S. invasion; however, international bodies could not effectively challenge calcified assumptions about Iraq’s nuclear program in a matter of months, even though they identified holes in the Bush administration’s case for war.

Iraq’s nuclear history is a saga of missed signals and misplaced confidence. For years, Saddam ran a clandestine weapons program under the IAEA’s nose. The Gulf War inadvertently exposed it, highlighting gaps in global safeguards regimes and triggering reforms. In the years that followed, the international community dismantled a recalcitrant regime’s nuclear weapons program, yet it did not trust its successes, in part because Iraq obstructed and politicized inspections, amplifying inherent uncertainties. Without recourse to credible channels or baseline knowledge about its capabilities, Baghdad was at the mercy of its own reputation when U.S. leaders misconstrued its actions, paving the way for a string of policies that proved disastrous for both Iraq and the United States.

Iran’s Nuclear Thinking

Like Iraq, Iran has a history of covert nuclear activities, and its nuclear program has been the subject of contentious diplomacy and coercive pressure since these efforts were exposed in 2002. In the past, negotiations with Tehran have placed transparency front and center. The JCPOA, specifically, took an innovative approach to oversight, and Iran accepted measures that exceeded traditional safeguards commitments, including remote monitoring of uranium enrichment levels, verifiable constraints on research and development, heightened scrutiny of procurement practices, and robust monitoring of facilities not normally subject to oversight, such as centrifuge manufacturing plants. Iran also agreed to resume implementation of the Additional Protocol (AP), a legal instrument that enhances the IAEA’s ability to detect undeclared nuclear activities by increasing its access to information and key locations. (The AP was designed to address the gaps in conventional safeguards exposed by programs like Iraq’s.)

In 2018, the Trump administration pulled out of the JCPOA and imposed “maximum pressure” sanctions on Iran, even though U.S. intelligence and the IAEA assessed that Tehran was complying with the deal. Still, the Iranian regime conspicuously upheld supplementary monitoring and verification provisions. This continued after 2019, when Tehran began walking away from other commitments, such as limits on the size of its stockpile of enriched uranium and the level to which it could enrich. While the dynamic was hardly ideal, effectively turning the IAEA into stenographers of Tehran’s noncompliance with the JCPOA, Iran’s continued cooperation with the agency offered some mechanism of reassurance, affirming Iranian advances while validating its assertions of self-restraint.

Since 2021, however, relations between Iran and the IAEA have devolved. After the Israeli assassination of a prominent Iranian nuclear scientist, Tehran confirmed that it would stop implementing the Additional Protocol and revert to its baseline safeguards agreement. Although the IAEA negotiated stopgap arrangements in which Iran agreed to leave supplementary monitoring equipment in place, inspectors have not been able to access key facilities or retrieve relevant data. Earlier this year, IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi acknowledged that the agency had lost “continuity of knowledge” over aspects of Iran’s nuclear program.

After years of economic pressure, Tehran has increasingly wielded transparency as a diplomatic cudgel. For example, when the IAEA Board of Governors censured Iran for unexplained traces of fissile material in June 2022, the regime instructed workers to remove monitoring and surveillance equipment that had been installed pursuant to the JCPOA. And while Iran has not expelled the IAEA, in September 2023, it used a process known as de-designation to bar a number of experienced inspectors, prompting Grossi to condemn Iran’s “disproportionate and unprecedented unilateral measure” that disrupted the agency’s mandate.

Although the U.S. intelligence community continues to assess that Iranian leaders have not decided to build a nuclear weapon, the aggregate effect of increased nuclear weapons capacity and diminished international oversight feeds pernicious uncertainty. Deteriorating regional security dynamics, including Israeli strikes near Iranian nuclear facilities and the degradation of Iranian proxies, render the situation even more volatile, and could make Iran’s nuclear program more central to its defense strategy.

There has already been a shift in Iranian rhetoric: Policymakers have begun to brandish the country’s nuclear threshold status to deter certain actions, including attacks on nuclear facilities. Following Israeli strikes in April, an adviser to the supreme leader warned that, “We have no decision to build a nuclear bomb but should Iran’s existence be threatened, there will be no choice but to change our military doctrine.” Experts have also emphasized that the only thing standing between Iran and the bomb is a political decision. As the head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization Mohammad Eslami put it in January 2024, “This is not about [us] not having the capability. Rather, it is about us not wanting to do this.”

Weighing the Risks and Rewards of Nuclear Oversight

Facing deteriorating regional security dynamics, Iranian leaders might conclude that increasing the ambiguity surrounding their nuclear program would make other parties think twice before escalating. Yet experience suggests that curtailing international oversight yields limited leverage and incurs significant liabilities.

The risks presented by insufficient oversight are not static; uncertainties compound over time, and Iran’s expanding capabilities exacerbate these dynamics. International policymakers would already have to respond to plausible indicators of Iranian proliferation more quickly, and with less information. For example, Iran claims that it is not enriching uranium beyond 60 percent; although this vastly exceeds the requirements of its civilian program, it is still a (quick) technical step away from the 90 percent levels usually used in nuclear weapons, which experts assess Iran could achieve within a few days. In January 2023, however, the IAEA detected uranium particles enriched to 83.7 percent at an underground facility in Fordow, as well as undeclared modifications to centrifuge cascades enriching uranium to 60 percent. While the IAEA ultimately assessed that these discoveries did not indicate Iran was diverting highly enriched uranium from this facility to a covert weapons program, it would be harder to evaluate the source and significance of such discrepancies and find viable off-ramps without stable communication channels and baseline transparency. Obscuring Iran’s enrichment activities would also widen the scope of possible miscalculation. Although Iran would still need several months to assemble a nuclear device after amassing enough weapons-grade material, activities associated with weaponization can be concealed at small undeclared facilities or military sites, making them harder to reliably detect.

Diminished international oversight also increases the burden on observer countries’ national intelligence services, injecting elements of interpretation and bias that can prove destabilizing, as the Iraq experience illustrates. To be sure, some nuclear programs, including Iran’s, may be heavily penetrated by foreign intelligence services, but forcing the world’s decisionmakers to rely exclusively on gathered information, without reliable access to sites of interest or the ability to triangulate with official sources, amplifies the risks of miscalculation.

Although it may seem aspirational, diplomacy remains the best way to avert worst outcomes. Iran’s nuclear program is sufficiently advanced, and sufficiently dispersed, that a military strike would only delay progress and likely harden Tehran’s resolve to acquire weapons. For now, comprehensive agreements like the JCPOA are improbable, given instability in the region and the lack of consensus among the great powers. Since invading Ukraine, Moscow has gone from pressuring Iran not to proliferate to shielding it from international censure, making it harder to impose additional pressure on the regime. Iran also has reservations about the United States’ ability to deliver sanctions relief and maintain agreements across political transitions.

Still, targeted measures to restore transparency are worth pursuing, for all parties involved. At this point, policymakers should focus on filling in the lacunae about Iranian capabilities that have emerged since 2021 and reestablishing continuous monitoring at key facilities. Left to fester, gaps in knowledge can become sticking points in future negotiations, and minefields in future crises. Under conditions of mistrust, routine oversight can establish credible baselines, narrow speculation, and facilitate viable off-ramps.

Iraq’s decision to conspicuously curb cooperation with the global nuclear order offers a cautionary lesson for Iran and the international community. Although flouting institutions like the IAEA may be provocative, it is not necessarily productive. Reestablishing verification baselines after periods of disruption often takes longer than policymakers anticipate. Persistent gaps in monitoring impede diplomatic resolution; coming back from termination would be even harder. Instead of increasing leverage, nuclear ambiguity could lead to missed signals and misread intentions. Curtailing oversight would also make it harder for all parties to step back from the brink in a crisis, amplifying the risks of a wider regional war. As Baghdad discovered, states that are deemed untrustworthy struggle to issue credible reassurances without proven verification mechanisms. In a volatile moment, both Iran and the United States should keep this in mind; otherwise, we may all be echoing Joni Mitchell’s lament: “don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got til it’s gone.”