This essay is part of a series of articles, edited by Stewart Patrick, emerging from the Carnegie Working Group on Reimagining Global Economic Governance.

The rise of neoliberalism did not occur in the same way everywhere. It rose in consolidated democracies like the United States with the election of president Ronald Reagan in 1980. Chile implemented neoliberal reforms in the 1970s during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. In Brazil and many other countries—such as Portugal, Greece, Spain, Türkiye, Argentina, and other countries in Latin America—the rise of neoliberalism coincided with processes of democratization or redemocratization, which makes the picture much more complex. As Rajesh Venugopal correctly argues, the question is not to “take neoliberalism as a given body of textual knowledge in need of interpretation, or as a self-evident real world phenomenon or field of practice in need of abstraction,” but to examine “what the word has come to mean, how it is used, and what the consequences are thereof.”

It was the worldwide consolidation of a far-right alternative in the second half of the 2010s that allowed the progressive wing of the neoliberal order, in decline but still in power, to formulate the project of a transition to a post-neoliberal order that would remain under its control. This possible transition within the order only became feasible because the sole alternative posed in democratic countries has been a choice between a new progressivism and authoritarianism. In this imagined transition, neoliberal forces are not simply defeated but also are given the possibility of converting to a “new order” or a “new consensus.” This transition within the order aims to go beyond neoliberalism and to avoid more or less generalized wars at the same time.

What gives declining neoliberalism the conditions to negotiate its own succession is both a political framework, reduced in many places to the abovementioned alternative between a new progressivism or authoritarianism, and the fact that the new progressivism currently holds considerable positions of power in institutional terms. However, the typical “top-down” vision of such a possible transition often obscures the social roots that actually support its viability. In social terms, neoliberalism has not been entirely defeated. Neoliberalism has been responsible for profound and lasting transformations; it has laid down social roots whose depth still requires a more precise assessment.

All these unfolding processes may be found in Brazil. Yet the case of Brazil is also characterized by a paradox: a mismatch between domestic political and broader geopolitical divisions. The growing calls for a reorganization of capitalism beyond neoliberalism are part of an ongoing process of deglobalization, unfolding in a geopolitical reconfiguration that runs the risk of assuming, ultimately, a militaristic and warlike character. In Brazil, the mismatch between politics and geopolitics has led to a zero-sum game when it comes to maintaining democracy and escaping a neoextractive trap. Any politician on the side of the new progressivism, from a geopolitical point of view, lacks the means necessary to fight the far-right on nationalist grounds. Successfully fighting the far-right on nationalist grounds, likewise, detracts from the new progressivism’s geopolitical agenda. This is the current impasse faced by Brazil—and maybe not only Brazil.

The Neoliberal Aftermath in Brazil

Over the past forty years, Brazil has experienced nothing less than a structural change in the correlation of social, economic, and cultural forces. In terms of share of gross domestic product (GDP), agribusiness and mineral extraction have surpassed the processing industry. This shift has reached the point where some consider manufacturing to be “on the brink of extinction” in Brazil, whether in terms of GDP share or of productivity and exports. It was in this upward movement that the term “agro” (as in “agribusiness”) emerged, with an increasingly influential and powerful political-electoral representation and with its own culture—one that has managed to reach the entire country.

It is important to stress that financial markets did not object to this political takeover by agribusiness. Quite the opposite: it did not matter what type of wealth was produced as long as it was “financializable” wealth, hence the markets’ alliance with this project. The same market forces also encouraged attacks on any subsidy given to industry, without a single word being said about the gigantic subsidies given to agriculture. This is how neoliberalism has turned not only Brazil but also most of Latin America into a neoextractivist region. The globalization of the principle of “comparative advantages” has reinforced the deindustrialization and primarization of Latin American economies, which have focused increasingly on the production and export of commodities to industrialized countries.

The political resilience of neoliberalism in Brazil has been strengthened by religious trends. The country has experienced an exponential growth of evangelical denominations. Although numbers from the last national census have not been released yet, between 31.8 percent and 39.8 percent of the Brazilian population are expected to identify as evangelicals. In the thirty years from 1980 to 2010, the percentage of evangelicals went from 6.6 percent to 22.2 percent. In the same period, the percentage of Catholics decreased from 89 percent to 64 percent of the population, and is expected to reach around 50 percent in the new census. Evangelical Christianity is an increasingly influential culture and has a powerful political-electoral representation. Together with large contingents of the police forces and the armed forces, these evangelical groups have expanded their political horizons. Increasingly, this emerging coalition aspires not simply to be in government, but to govern, to dictate the country’s direction.

The first political moment in which these different forces converged was when Jair Bolsonaro emerged as an antisystem candidate in 2018, and became, in effect, the leader of this new coalition. He was also a direct heir of the military dictatorship (1964–1985), and he was convinced that redemocratization was responsible for all the country’s ills. Bolsonaro’s electoral victory in 2018 represented the far-right’s rise, with him at the head of a coalition that intended to impose its program at any cost, even Brazil’s democracy.

The emerging coalition that backed Bolsonaro in 2018 had as its goal the consolidation, in political and institutional terms, of the economic and social power its members had acquired in the previous decades. Bolsonaro may have run as an “outsider” candidate—even though he had served in Congress for twenty-eight years—but he represented a coalition of forces that already had significant power, save for control of the presidency. Although the Brazilian Electoral Justice in June 2023 declared that Bolsonaro himself was ineligible to participate in the 2026 election, Bolsonarismo remains a driving force in Brazilian politics, whoever its candidate may be.

The Neoextractive Trap

The threat posed by Bolsonarismo, combined with enduring components of neoliberalism, has reinforced the neoextractive nature of the Brazilian economy, notwithstanding Lula’s return to the presidency in early 2023. Indeed, Lula’s progressive administration is in the paradoxical position of not being able to give up neoextractivism, as doing so would mean surrendering Brazil’s sole source of income capable of preventing an economic and social disaster. Without that revenue stream, progressivism will not likely continue to win elections. If progressive coalitions are defeated, the opposing coalition (led by the far-right) will not hesitate to step on the accelerator of neoextractivism, using its immediate results to obtain political-electoral gains. At the same time, if progressivism does not give up on neoextractivism, the opposing coalition led by the far-right will have already won, because its economic program will have won.

Public investment in Brazil has reached historic lows in the past decade. One indicator of this reality is that there is no fiscal space to fund the country’s energy transition. Only concerted international action to alleviate Brazil’s national debt and generate new sources of funding would open the possibility for meaningful ecological transition. Such financing would give Brazil, and other countries like it, a chance to reverse the “reprimarization” of their economies that has occurred in recent decades. It would also open extraordinary opportunities for fighting climate change.

Unfortunately, recent efforts to reform international financial institutions, including the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, are unlikely to resolve Brazil’s financial predicament even if these reforms are successful. First, any such new funding is likely to be “too little, too late”; the far-right is already at Brazil’s door. For the time being, Brazil’s only prospect of somehow alleviating its fiscal entrapment is by exploiting its oil. In 2016, Brazil became a net exporter of oil for the first time, and today oil and its derivatives rank second and fourth in the country’s exports. Brazil’s state oil company, Petrobras, “is planning such a rapid increase in oil production that it could become the world’s third-largest producer by 2030.” Indeed, it “already pumps about as much crude oil per year as ExxonMobil.” The obvious downside of this strategy, of course, is that it would both reinforce Brazil’s reliance on extractivism and undercut the nation’s climate goals.

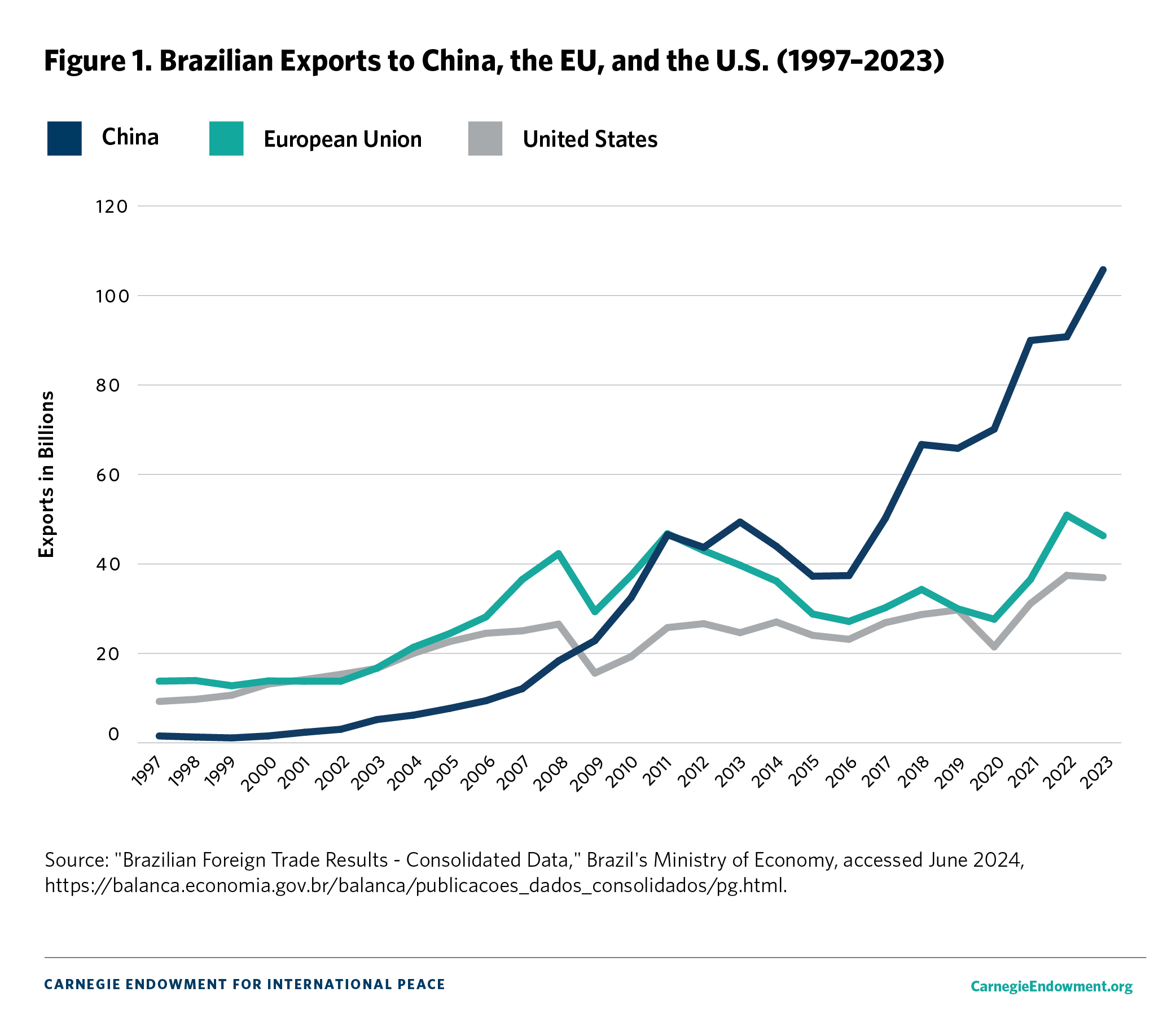

Brazil’s trade dependencies may also limit its room for maneuver. The country cannot afford to decouple from economic partners that are autocracies and one-party regimes. Deglobalization in the form of decoupling is reserved only for those who can afford this luxury. “Friendshoring” as a commercial and/or national security policy is reserved for those who can afford to choose their friends. A comparison of Brazilian exports to China, the United States, and the European Union (EU) may give a sense of how impossible it would be for Brazil to join the United States and the EU in their decoupling from China—or Russia, for that matter. As figure 1 shows, Brazil is far more dependent on exports to China than to either the United States or the EU.

At the same time, the United States and the EU are not taking any measures to signal their intent of substituting China as the main destination of Brazilian exports, such as in the form of an ambitious global green reindustrializing program. When there are so many calls for a “new Bretton Woods,” it might be expected that those calls would be accompanied by a Green Marshall Plan of some sort. Without some initiative in that direction, in which commodity-dependent, emerging market economies can obtain major financing for adopting climate- and nature-friendly policies, countries like Brazil will remain the prey of the same neoextractivist trap that reduces the political space to a choice between fighting climate change or fighting the far-right. In other words, unless progressivism goes beyond national battlegrounds and also shapes geopolitical divides, it will be hard for countries such as Brazil to avoid the neoextractivist trap. Such a move is not in sight, at least for the time being.

The author thanks Olavo Ximenes for valuable assistance.

.jpg)