How Circular Cooperation Puts Reciprocity at the Heart of a New Africa-Europe Relationship

In the first two decades of the twenty-first century, European Union (EU) institutions spent $279 billion in global development cooperation, of which roughly 40 percent went to Africa.1 Investments like these have achieved some important successes.

For example, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and Gavi, the vaccine alliance, are two initiatives which benefit from significant European contributions. Together, they helped contribute to saving more than 65 million lives.2 A strong international focus on women’s rights in development programming, including the education of girls, catalyzed paradigm and budgetary shifts in many countries receiving aid.

But as the second quarter of the century approaches, efforts to update aid and development cooperation seem tired. Initiatives to expand and improve international cooperation to meet the scale of the needs when it comes to climate change and development challenges come up against political barriers presented as inevitable facts that cannot be changed.

The dominant worldview that has shaped the Africa-Europe partnership—and the broader development cooperation landscape in which it sits—is based on vertical cooperation: the idea that so-called advanced countries support so-called developing countries with resources, know-how, and technology. In a rapidly changing world, this worldview is both outdated and inefficient. Other terminologies have been developed. Cooperation between countries in the Global South, often termed “South-South cooperation,” is based instead on horizontal cooperation, and some have proposed triangular cooperation between countries and international institutions. Yet, even with these developments, partnership paradigms maintain a power dynamic of cooperation between donor and recipient.

We propose a new way of thinking about partnership: circular cooperation, where partnerships are based on consistent iterations, learning, and mutual problem-solving. In a world of rapid change and disruption, this model will lead to both greater impact and improved trust and dignity between Africa and Europe.

Time to Go Deeper

Throughout history, major crises have led to structural reforms. The Black Plague, for instance, led to daughters in Europe being granted land rights for the first time. A cholera epidemic in London in 1854 spurred action to address the city’s “Great Stink” by designing the modern sewer system still in use today.3

World War I led to the creation of the League of Nations. The Great Depression yielded the New Deal in the United States. World War II led to the creation of the United Nations, the Bretton Woods institutions, and the Marshall Plan.4

The COVID-19 pandemic is one such crisis. In the wake of the pandemic, which killed more than 7 million people,5 there is one consistent silver lining: a new readiness to name structural injustices. Whether related to race, gender, or geography, people around the world are calling for fundamental changes in global institutional architecture in a way that seemed peripheral only a few years ago.

Young people (in Africa, Europe, and elsewhere) seem particularly impatient with glossing over unpalatable historical realities or tinkering with manifestly outdated approaches. Whereas once society considered activists and advocates being radical (which, etymologically speaking, means getting to the root of things) as a surefire way to lose political support in global campaigning, it is now widely considered odd not to contextualize even the shortest-term objectives within a longer-term transformational narrative. Now, the world’s largest foundations fund activities related to postcapitalism, postneoliberalism, and postcolonialism. For example, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation has a program entitled “Beyond Neoliberalism,”6 while the stated goal of the Ford Foundation’s International Cooperation program is to “promote social justice and disrupt inequality within systems of global governance and international cooperation.”7

This debate is not new. But it has a renewed energy. In 1976, I. William Zartman, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, published an essay in Foreign Affairs arguing that, despite decolonization, the European Community intentionally maintained a level of African dependency through its trading, military, and aid cooperation.8 If the world has moved from an era of improving aid to decolonizing it, what does such a transition mean for the partnership between Africa and Europe?9

In some ways, the cooperative relationship between Africa and Europe has already been evolving. There has been a shift from transactional engagements to more mature international partnerships, at least in rhetoric. Upon taking office, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen identified a “partnership of equals” with Africa among her top priorities.10 European support for the African Union (AU) as a continent-wide body is refreshing for those frustrated by the history of fragmented bilateral relationships. Notably, European Council President Charles Michel was an early supporter of a proposal to grant the AU a permanent seat at the G20.11

But the progress at the beginning of this century—as part of the Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation,12 which emphasized country ownership, inclusive partnership, and transparency—has, if anything, been reversed as financial crises have deepened in both Africa and Europe, in part as a result of the pandemic.

In Europe, restricted budgets have meant an increasing focus on narrowly formed conceptions of quantifiable “results,” which incentivizes investments in shorter-term, more easily measurable impacts and recentralizes decisionmaking in what are called “donor” capitals (despite the new language of “localization”). In Africa, officials of cash-strapped governments fly north in journeys reminiscent of the ones their predecessors made in the 1980s, to argue for stimulus packages and debt relief.

The arrival in both Africa and Europe of large-scale investment from China and other Global South giants has busied the geopolitical landscape, offering opportunity and risk in equal measure and providing African leaders with leverage in their negotiations with traditional development partners.

But the response of some Europeans is straight out of the playbook of twentieth-century power games. This repeated script was displayed at the Munich Security Conference in 2023, when Italian Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani said, “To leave Africa in Chinese hands is a big mistake for everybody here.”13

Cultural attitudes are changing. African economies are evolving, European economies struggling, and major Global South players emerging. The old paradigm is dying, but a new one struggles to be born.

The Africa-Europe relationship is hemmed in by a narrative that prevents it from responding to the real needs of the two continents in the twenty-first century. For example, while the European Commission has changed the name of its Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development to International Partnerships, power dynamics and institutional mandates mean the focus remains on managing aid budgets while the trade-focused parts of the commission view their role as one defined by hard negotiation for European interests in what some consider a mercantilist approach to negotiating with African countries. Africa has already changed its approach to relationships with China and Russia, so without a significant paradigm shift in Europe’s understanding of cooperation, progress will continue to be constrained.

Developed and Developing

Although the terms “first, second, and third world” are no longer the language for development economists, the fundamental division they describe remains at the heart of development cooperation in the idea that some countries are “developed” or “advanced” while others, the majority, are “developing” or “emerging.

The unspoken premise is that progress and resolution to human society’s challenges are to be found in one part of the world—namely, Europe and North America—and other parts of the world need to look north for answers and help.

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which were adopted in New York in 2015, appeared to have broken through this narrative with universal aspirations for all countries, not just so-called developing countries.

However, the development cooperation narrative has lagged behind. The headline outcome of the EU-Africa Summit in February 2022, while couched in language of common values and shared partnership, focused on the announcement of a €150 billion EU investment package for Africa.14 South African President Cyril Ramaphosa’s response was to doubt whether Europe would follow through on its pledge.15

It is true, of course, that wealthier countries are in a better position to provide funds, but funding is only one aspect of cooperation, and it is obviously false that the countries of Europe cannot benefit from solutions designed in Africa and that African countries cannot contribute to development in Europe, despite more limited financial resources.

Toward Circular Cooperation

The pandemic was better managed in many African countries than in European countries,16 and some African countries are ahead of the curve at adapting to climate change and managing the associated loss and damage. For example, in 2019, two-thirds of Kenya’s energy came from bioenergy. It is pioneering the generation and adoption of geothermal and carbon capture and storage technology.17

These advances are commonly acknowledged in the modern world of international cooperation, but there is still no program model or institutional framework to ensure in practice that all countries are able to contribute what they can to solving global challenges.

In contrast to this supposedly vertical, Global-North-to-Global-South way of thinking, the concept of South-South cooperation—which emerged from the Buenos Aires Plan of Action in 1978—has long been presented as offering horizontal cooperation between peers, with both parties benefiting from collaborative projects.18 But the Global South covers a vast range of countries, and relationships can be just as “vertical” as North-South ones when, for instance, China (which has a per capita gross domestic product, or GDP, around $12,500) engages with Zambia (GDP per capita $1,100).

Continuing the geometric imagery, the concept of “triangular” cooperation has recently come to the fore, encouraging communities of different wealth levels to engage in development projects in a new way, building on complementary strengths.19 Typically, an organization based in a high-income country provides funding, partners from a middle-income country provide expertise, and a low-income country is the target for development impact. However, even with this apparently modern triangular approach, the colonial narrative persists, and “vertical” cooperation is maintained by situating a poor country supported in its development by richer countries.

These three models need to evolve further. They don’t recognize the twenty-first-century patterns of education, mobility, and technology diffusion that make it increasingly possible for financially poorer groups in Africa and Europe to lead change based on profound knowledge and experience. They don’t recognize that vulnerability exists in countries of all wealth levels, including in European countries. And they don’t recognize that, facing an uncertain future, European publics increasingly want to ensure that they are getting something out of international cooperation. That something should be access to the remarkable human capital, ingenuity, and innovation that comes from the need to solve problems in remarkable resource constraints.

A modern approach to Africa-Europe cooperation should emphasize reciprocity. Circular cooperation would be the final rejection of the colonial thinking that has so undermined relationships between the two continents. It would break down the donor-recipient divide and treat all countries as both co-contributors and co-recipients of ideas, experience, resources, and support. Where one country has more material resources, it would contribute more money, but that would not accord it leadership status. All countries would jointly recognize and implement a program of work from which all would benefit in different ways.

Circular cooperation would place dignity in the hands of Africans, their countries, and their communities, as well as Europeans. Too often the psychological aspects of development are overlooked by bean-counter approaches to impact, but without the self-esteem associated with the power to contribute, communities are less motivated to build change for themselves, let alone others, meaning that even supposedly hard outcomes (measured, for example, in lives saved or children educated) are reduced. In fact, people everywhere routinely choose dignity over economic outcomes; some governments reject help from abroad, even when their populations remain extremely poor.

The impacts of circular cooperation will be broader, as both African and European countries benefit from collaboration and learning. Today, too much value is being left on the table by European stakeholders who are missing the opportunity to provide benefits to their own communities, despite having real problems to solve. It is likely that over time this way of viewing international cooperation will be popular with both Africans and Europeans. There are mixed messages on public support for international cooperation in Europe, but some European leaders seem increasingly inclined toward mutual cooperation to prevent, for example, a pandemic crossing borders or multiplying climate crises.

The principles behind circular cooperation are already evident in a new approach to international public finance called global public investment (GPI), which has been developed through a co-creative process involving organizations and experts across the world. It emphasizes the critical role of concessional international public finance, particularly grants, and envisages a system for meeting global ambitions through long-term, reliable investment in the goods, capital, and infrastructure they require and responding to global challenges such as climate adaptation, pandemics, and social protection. Without undermining the responsibility of the richest countries to pay their fair share, GPI comprises three universal principles reflecting a circular approach to addressing the world’s challenges: all contribute, all benefit, all decide.20

Breaking Down Conceptual Constraints

GPI’s emphasis on reciprocity also breaks down a range of other conceptual constraints. For example, development economists tend to think that ending extreme poverty—a concept defined by World Bank economists based in Washington, DC—is the only real goal of development cooperation; when the worst forms of poverty are ended, the job is done. Instead, reciprocity would involve not just containing the direst situations but also consistently solving problems, improving living standards, identifying opportunities for increased sustainability and prosperity, and creating convergence with the living standards of citizens of wealthier countries.21

Increasingly, governments and international analysts and agencies (including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the International Monetary Fund) are emphasizing the problems of inequality and the crucial redistributive role of taxation, picking up on the work done for decades by civil society and academics. Whether the 2008 financial crisis ushered in a new era of global inequality, as many claim, or simply noticing it more as it increases in Western countries, deep inequality is entrenched in most countries. The heart of political struggle revolves around trying to persuade the “haves” to share wealth and opportunities more generously with the “have-nots.” These challenges cannot be resolved in a short space of time, say three, five, or ten years, and they are susceptible to backsliding as much as to progress. Policymakers need to better acknowledge the long-term nature of political change given this stubborn reality.

Through a reciprocal approach to cooperation, another fundamental conceptual constraint is challenged: the idea that the development process has a time horizon. A common slogan in the world of development cooperation is that “our job is to do ourselves out of a job.” But the idea that countries move along the same development continuum as their economies grow is false; countries at similar levels of income per capita can have vastly different institutional arrangements and types/standards of public service provision.

Perhaps more importantly, there are constantly new challenges requiring international cooperation; natural disasters, conflict, disease outbreaks, and macroeconomic shocks can set countries back decades on some development indicators, as the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated. There should be no exit strategies for cooperation; rather countries should cooperate through learning, adapting to change, and resolving challenges together as they arise. Circular cooperation would not be a time-bound process (any more than working together on technology and security is) but a permanent and evolving direction of travel.

Reciprocal forms of cooperation also, quite obviously, require an equitable form of governance with a focus on voice, ownership, and accountability. For cooperation to be successful it has to be managed well, grounded in transparency and fairness, and aligned to national priorities and contexts. It has to be sufficient, predictable, and sustainable. These attributes are not delivered well by the present system. Africa-Europe circular cooperation projects and institutions would be built by Africans and Europeans together, in contrast to an aid architecture built in Europe and the United States at a time when colonial attitudes were dominant. African and European countries could propose an equivalent of the Buenos Aires Plan of Action to inspire new approaches for modern, interregional cooperation.22

Conclusion: Clues From the EU and the AU

The good news is that clues to how to build this approach can be found close to home. Both the EU and the AU showcase what a reciprocal approach to cooperation within a region can look like: countries clubbing together to solve common problems. The goal of convergence is at the heart of the theory behind the EU’s Structural and Investment Funds and Cohesion Funds,23 whereby the EU’s wealthier countries, including some of the world’s major donors, transfer billions to poorer European countries, which are nevertheless wealthy by global standards. With the adoption of the SDGs, the door for applying EU-style thinking to a broader global context seems to be wide open.

Neither in Africa nor in Europe do countries metaphorically graduate from concessional assistance upon reaching a certain (arbitrary) level of income per capita. Notably, even the wealthier countries in the EU grouping, net contributors to the overall pot and some of the richest countries in the world, also benefit directly from EU grants. The money they receive is generally used to promote social cohesion, generate jobs, and invest in green growth in poorer parts of the country, as well as to support broader objectives such as culture and environmental sustainability.

Since their inception, the two EU funds have been about more than overcoming an arbitrary poverty line. While the EU’s and the AU’s funds both focus on poverty and social cohesion, with special funds for humanitarian responses, their thematic focuses go well beyond these concerns, looking at greater connectivity between countries, infrastructure development, job creation, small business development and entrepreneurship, research and innovation, and environmental protection.

The most important aspect of EU fund governance is that, because all countries pay in and all receive, all sit around the table deciding how funds should be spent—much in the way those backing a GPI approach propose. Critical to the theory underpinning the EU funds, and to garnering public support for this redistribution of wealth, is the recognition that reducing disparities in living standards and building shared infrastructure is important for the progress and security of all parts of the union, not just the direct recipients of grants.

This form of reciprocity has deep implications for the Africa-Europe partnership. Moving from one-way development cooperation to mutual circular cooperation will require not only a shift in worldview that sees every participant as an active contributor to finding solutions for all but also a new political narrative that does away with the harmful notion of international charity.

Circular cooperation will demonstrate the value to the citizens of both Africa and Europe and redesign institutional mandates in a way that redistributes power to all contributors. In an era of rapid change and significant disruption, the moment demands a type of partnership that puts dignity and reciprocity at its center.

About the Authors

Jonathan Glennie is a co-founder of Global Nation, a think tank that promotes an internationalist global future.

Hassan Damluji is a co-founder of Global Nation, a think tank that promotes an internationalist global future.

Notes

1 Author calculations from Sara Harcourt and Jorge Rivera, “Official Development Assistance (ODA),” ONE, https://data.one.org/topics/official-development-assistance.

2 “Results Report 2023,” The Global Fund, https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/results; and “Our Impact,” Gavi, October 17, 2022, https://www.gavi.org/programmes-impact/our-impact.

3 Will Tanner, “How Pandemics Spark Social Progress,” Politico, March 26, 2020, https://www.politico.eu/article/how-pandemics-spark-social-progress.

4 Amartya Sen, “A Better Society Can Emerge From the Lockdowns,” April 15, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/5b41ffc2-7e5e-11ea-b0fb-13524ae1056b.

5 Edouard Mathieu et al., “Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19),” Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cumulative-covid-deaths-region.

6 Larry Kramer, “Beyond Neoliberalism: Rethinking Political Economy,” William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, April 2018, https://hewlett.org/library/beyond-neoliberalism-rethinking-political-economy.

7 Ford Foundation, “International Cooperation,” https://www.fordfoundation.org/work/challenging-inequality/international-cooperation.

8 I. William Zartman, “Europe and Africa: Decolonization or Dependency?,” Foreign Affairs, January 1, 1976, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/africa/1976-01-01/europe-and-africa-decolonization-or-dependency.

9 Amruta Byatnal, “Deep Dive: Decolonizing Aid—From Rhetoric to Action,” Devex, August 24, 2021, https://www.devex.com/news/deep-dive-decolonizing-aid-from-rhetoric-to-action-100646.

10 David M. Herszenhorn, “Von der Leyen Ventures to the Heart of Africa,” Politico, December 8, 2019, https://www.politico.eu/article/european-commission-president-ursula-von-der-leyen-ventures-to-the-heart-of-africa-ethiopia-african-union.

11 Charles Michel, “Speech by President Charles Michel at the Mid-year Coordination Meeting of the African Union,” European Council, July 18, 2022, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/07/18/remarks-by-president-charles-michel-at-the-mid-year-coordination-meeting-of-the-african-union.

12 “Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, December 1, 2011, https://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/49650173.pdf.

13 “‘Leaving Africa in Chinese Hand Is Big Mistake,’ Says Top Italian Diplomat,” Africa Press, February 20, 2023, https://www.africa-press.net/eritrea/all-news/leaving-africa-in-chinese-hand-is-big-mistake-says-top-italian-diplomat.

14 “European Union–African Union Summit, 17-18 February 2022,” European Council, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-summit/2022/02/17-18.

15 “EU-Africa Summit Looks for ‘Fresh Start,’” DW News, February 17, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/eu-africa-summit-looks-for-fresh-start/a-60819733.

16 Anne Soy, “Coronavirus in Africa: Five Reasons Why Covid-19 Has Been Less Deadly Than Elsewhere,” BBC, October 8, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54418613.

17 “Kenya Energy Outlook,” International Energy Agency, November 22, 2019, https://www.iea.org/articles/kenya-energy-outlook.

18 “What Is ‘South-South Cooperation’ and Why Does It Matter?,” UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, March 20, 2019, https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/intergovernmental-coordination/south-south-cooperation-2019.html.

19 “Triangular Co-operation,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, https://www.oecd.org/dac/triangular-cooperation.

20 Global Public Investment, https://globalpublicinvestment.net.

21 See, among many examples, “Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want,” African Union, https://au.int/en/agenda2063/overview.

22 “Buenos Aires Plan of Action (1978),” UN Office for South-South Collaboration, https://unsouthsouth.org/bapa40/documents/buenos-aires-plan-of-action.

23 “EU Cohesion Policy: European Structural and Investment Funds Supported SMEs, Employment of Millions of People and Clean Energy Production,” European Commission, January 31, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_389.

Harmonizing the Climate and Energy Transition Agendas of Africa and Europe

In her 2023 State of the Union address, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen praised the impact of Europe’s green investments in Africa as investments in Europe’s prosperity. In her next breath, she turned to how “conflict, climate change and instability are pushing people to seek refuge elsewhere.”1 This is one example of how climate diplomacy largely frames the goals of investment in Africa as mitigating risks around issue-based climate concerns, such as peace, security, and migration.

But it is time to move away from discussions about vulnerabilities and weaknesses and toward the enlightened strategic autonomies of both continents, which can together form an investment partnership for mutual economic interests. The energy transition presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to align the geopolitical interests of both regions.

Africa-Europe climate diplomacy should adopt an integrated approach linking climate and development issues as part of a broader economic development planning and investment process that could transform the economies of both continents.

In this light, both continents should take steps to mobilize low-cost investment in the energy transition, actively champion the future finance and investment trajectory of multilateral institutions, and actively participate in Africa’s economic diversification agenda.

Achieving Europe’s Climate Goals Depends on Good Neighborliness With Africa

Today’s geopolitical shifts in relation to tackling global climate issues are increasingly serving the economic interests of advanced economies. These powers are actively seeking to use national or regional climate goals to shape future energy markets and become frontier developers of green technologies.

The African continent is an increasingly strategic player and should be a priority for the European Union (EU) and for European countries for four primary reasons.2

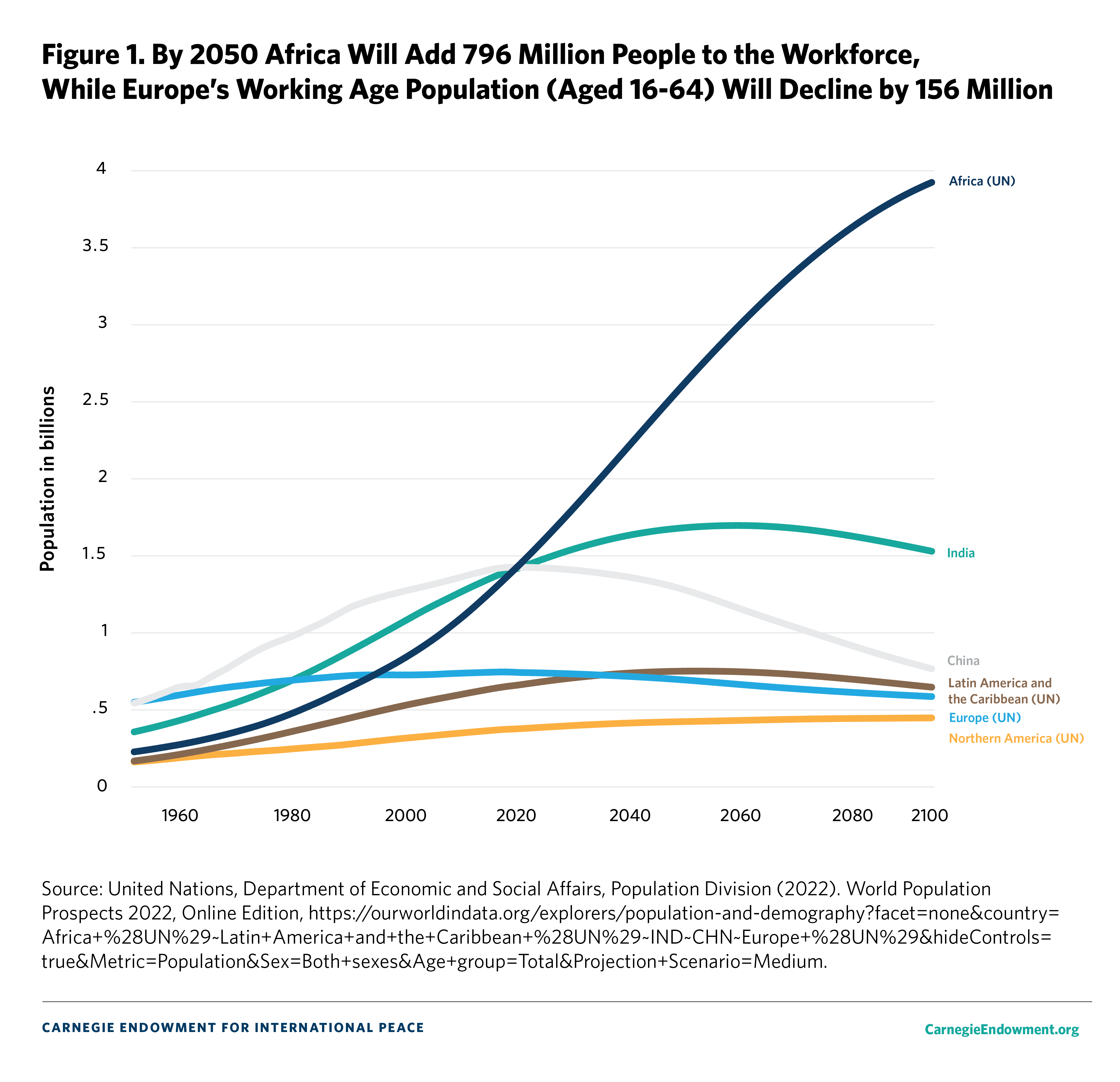

First, the size of Africa’s economy is projected to triple by 2040, with $5.6 trillion in business opportunities by 2025.3 While growth rates have decelerated as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Bank estimates that many of Africa’s regions will post growth rates of between 3 and 5 percent from 2020 onward.4 By 2050, Africa will have the youngest population in the world, the largest workforce, and the fastest rate of urbanization.5 This opportunity also presents a risk because jobs will have to be found for many young Africans, while the continent will face a range of climate vulnerabilities. But if these challenges are addressed through better policy choices and improved governance, the prosperity that ensues will play a role in addressing instability and social conflicts.6

Second, on the diplomatic front, Africa holds the largest share of votes of any region at the United Nations (UN). These votes cannot be taken for granted in a world where votes count on climate-related matters at the UN General Assembly, the World Trade Organization, and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change—where economic and new industrial development trajectories intersect.7 This impact became clear when Europe along with other Western nations struggled to corral African votes behind a succession of UN resolutions condemning Russia’s actions in Ukraine. Most African countries took the view that they did not want to be drawn into Europe’s conflict.8

Third, the war in Ukraine has made Europe more dependent on the supply of coal, natural gas, and oil from Africa—Africa’s gas supply to Europe is projected to double by 2050.9 This is a short-term economic imperative. Reducing gas supply from Russia has increased prices and impacted European industries.10 Yet, this is also hypocritical: one branch of EU climate diplomacy is calling for the world to decarbonize and for Africa to get off gas, while individual member states are negotiating new gas deals for European consumption.11

Fourth, Africa is rich in mineral resources needed for this new industrial revolution, and it has large land availability (especially for green hydrogen production). The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), for instance, has just over 50 percent of the world’s cobalt deposits and is responsible for 70 percent of global production.12 Ghana is poised to become a leading lithium producer, and Zimbabwe has an abundance of the mineral.13 Limited and unsecure access to critical minerals will likely undermine Europe’s competitiveness. The EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan (GDIP) for electric vehicles, batteries, electrolysis for green hydrogen, and renewables is highly reliant on a variety of critical minerals such as lithium, graphite, cobalt, nickel, copper, and others. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act, adopted as preliminary package by the European Parliament and the European Council in November 2023,14 is driven by the fact that the continent will need eighteen times more lithium and fifteen times more cobalt to meet its climate goals.15

Europe’s push for strategic autonomy can easily tie with Africa’s own pan-African ambition contained in the Agenda 2063 program, which aims to create an integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa.16 The idea of the African Union (AU) mirrors the European project of a unified political bloc, and the AU now represents fifty-five countries. It is reinforced with the recent creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which is one of the largest and most diverse free trade areas in the world.17

Europe’s experience in the creation of a common market gives it an advantage vis-à-vis other major powers. But a new model of economic partnership for mutual security and development between the two continents cannot be understood in isolation from increasing geopolitical competition between China, Russia, and the United States—not to mention other middle powers such as Japan, South Korea, and Türkiye.

Green Industrial Strategy

The trend toward industrial policy is of principal importance. The Joe Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is landmark legislation to support the United States’ energy transition through subsidies and tax breaks. The IRA has not only raised alarm bells within the EU but also with key members of the G7. Canada, for example, has warned against the United States fragmenting the Atlantic alliance with what it called a “carbon subsidy war.”18

The Norwegian company Yara International, which has operations across the African continent and is exploring new opportunities in East Africa, is also considering the United States as a key destination for fertilizer production. In an interview in the Financial Times, Yara’s CEO, Svein Tore Holsether, noted that Yara requires massive amounts of renewables to produce large quantities of clean ammonia green hydrogen—quantities that would require a scale-up faster than the current pace at which green hydrogen projects are being rolled out in Europe. These sentiments are coming on the back of the United States’ IRA, which is effectively a series of green subsidies for different clean technology pathways Washington is seeking to scale to build new industrial capability.19

In response to the IRA subsidies, companies like Yara have pressured von der Leyen, to take action.20 In response to the IRA, the EU published the GDIP to enhance the EU’s competitiveness and key industry and technology innovation within the geography of the EU.21 The strategies of the U.S. and EU plans all include a focus on the security of critical mineral supply chains, an area where China already has a lead.

China dominates the production of rare earth minerals and has secured key critical minerals supply chains and contracts in Africa. But this advancement is being countered by new competition; for example, the United States recently signed a memorandum of understanding with the DRC and Zambia on battery minerals.22 But, the EU cannot solely rely on its relationship with the United States to guarantee a security supply of critical minerals. The sudden announcement of the IRA by the Biden administration has demonstrated that Washington will pursue its own interests irrespective of its friendship with the EU.

Both the United States and the EU will have to contend with China’s strategy of wrapped state-to-state deals, sometimes also described as the Angola model. In this model, China agrees to extract mineral resources in exchange for Chinese state-owned companies building critical infrastructure or providing competitive, low-cost loans.23 Europe’s climate and development diplomacy will increasingly have to contend with alternative financing and development models from its economic rivals.

The EU will need African sources of supply and will have to develop a constructive partnership model for critical minerals, which are needed in wide-ranging new areas of technology modernization. This need is an opportunity to shape new areas of cooperation as Europe looks to reduce its dependence on China for critical minerals and the production of clean energy technologies.24 In order to boost the security of its own critical minerals supply, the EU has established the European Raw Materials Fund, which aims to raise €100 billion.25

This reactionary approach to industrial policy risks hindering the trust between Africa and Europe. The GDIP, touted in Europe as beneficial to Africa, actually risks undermining Africa’s market access. New standards, rules over market access, and carbon border tax adjustments, which have been read by Africans as inward-looking and a new form of protectionism, could harm the African continent rather than boost prosperity.26

African Expectations of Europe

Recurrent summits and other diplomatic engagements between the EU and AU often seem like rituals that must be performed, and a widening gap is emerging between the rhetorical ambition expressed by both parties and the delivery of developmental outcomes. The EU concerns itself with pushing normative outcomes such as governance, democracy, peace, and stability, hoping that this will enable development.

On the other hand, China is supporting African states by providing concrete, real-economy investments and locking in a range of deals on key minerals, information technologies, and knowledge transfer. These deals are not without costs, particularly when it comes to debt burdens, but highly visible results are delivered rapidly. These contrasts—alongside China’s perceived anticolonial history and recent track record of lifting millions of people out of poverty27—are shaping the optics that ought to indicate to the EU that it needs to up its game.28

To signal that it is serious about a new kind of relationship, the EU should consider the interests of African countries, principally the following.

First, Europe should stop treating climate change as a spillover risk to Europe or relegating its importance to aid projects that deal with adaptation and resilience. The entire framework of climate diplomacy must be reconceptualized as an investment partnership for mutual economic interests rather than secondary to them.29

The EU could use its clout to mobilize the G7 and wealthy countries behind an African climate and development agenda. This should include arguing for better African representation at key decisionmaking tables, building on the approval of a permanent seat for the AU at the G20 and arguing for effective debt relief programs aligned with much cheaper sources of finance that are embedded with climate objectives.30 Reducing debt distress enhances the fiscal space of governments, supports sustainable growth, and improves new capital-raising efforts from public and private sources with better credit ratings. Interestingly, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which held the 2023 presidency for the UN climate change conference known as COP28, is targeting highly indebted countries in Africa with finance packages to build out their energy transitions. A UAE deal with Zambia involves $2 billion (€1.84 billion) in phased installation for 2,000 megawatts of solar generation capacity and is described not as a loan but an investment with the Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation (ZESCO).31

Second, Africa needs significant sources of cheap financing to scale up its infrastructure and deliver Africa’s Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA), an African Development Bank initiative that aims to advance crucial regional and continental infrastructure sectors. The Africa-Europe Investment Package of €150 billion announced at the 2022 AU-EU Summit, part of the EU’s €300 billion Global Gateway infrastructure initiative, should materialize quickly.32 This could undergird the EU’s mantra of a values-driven premise and high standards for infrastructure. The pledge is also aligned with the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, which also aims to advance public and private investments in sustainable, inclusive, resilient, and quality infrastructure.33

Third, Europe should actively champion the future finance and investment trajectory of multilateral institutions within its own domain and within the Bretton Woods framework. Two important initiatives, the Bridgetown Initiative led by Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley and the Summit for a New Global Financial Pact led by French President Emmanuel Macron,34 have encapsulated not only broader reforms but also have created coalitions of governments and non-state actors to champion proposals to increase the supply of finance for climate and development agendas in developing countries.

Fourth, the EU should participate in Africa’s economic diversification agenda. The EU is pushing for a more restricted market through its Green Deal and the introduction of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), but these instruments are too blunt and will certainly be damaging, especially if the current approach to the CBAM is not reconsidered.35 Some research estimates suggest that the CBAM, if implemented in its current form, would knock as much as $16 billion per year off of Africa’s GDP.36 The elements of the mechanism that penalize African exports with embedded carbon intensity—without room for exemptions and leeway for adjustments—will be harmful to sectors that are key for Africa’s export-led growth and foreign exchange. Key sectors that are likely to be impacted by the CBAM are automobiles, steel, cement, petrochemicals, and fertilizers. The EU should consider a formal structure and process to facilitate more meaningful discussions with key African states most likely to be adversely impacted by the CBAM. For example, an approach is already being provided for the German government’s climate club, which is aimed at providing a parallel forum for high emitters to engage each other directly on decarbonization solutions that involve trade or nontrade measures that impact their exports.

Fifth, the EU and African countries should partner on a shift to an integrated approach linking climate and development issues as part of a broader economic development planning and investment process. This shift should build on an assessment of the economic context and development trajectory of African countries that highlights the priority climate risks and investment opportunities. Models such as the much-vaunted just energy transition partnerships (JETPs), which were started in South Africa and are now being mimicked elsewhere on the continent, are useful country platform models to align cheap sources of finance with energy transitions and economic diversification.

Via the European Investment Bank, the EU has started a journey toward a comprehensive approach using the South African JETP as a test case to an approach the Global Gateway initiative can adopt more broadly for clean energy infrastructure deals on the continent. JETPs are useful models to collapse several things: achieving high climate ambitions, aligning the financing package to increase fiscal space and reduce debt levels, and supporting rapid policy reform and implementation on the back of a finance package.37

These deals also allow EU-based firms to play a leading role in the energy transition space and for private sector finance to be crowded in. But, for these deals to work, the EU has to develop fast-track mechanisms and should consider new mandates and roles for the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. African countries should increase the capacity at the African Development Bank and Africa Export-Import Bank to participate meaningfully.

Finally, the EU should shift to a developmental and investment approach when it comes to critical minerals. The EU should prioritize value addition in the extraction of critical minerals, following the example of the United States in its partnership with Zambia and the DRC to strengthen electric vehicle battery value chains.38 Working with producer countries of critical minerals, such as Zambia and the DRC, to enhance and improve sourcing quality and standards, embedding more human rights and social justice measures in critical minerals extraction processes, would not only create jobs and build prosperity but also would help ensure that governance in host countries and firms exporting these critical minerals adhere to best practices.39 This could be part of a broader efforts to address what is perceived to be a fragmented trade policy when it comes to Africa and to integrate EU trade actions with the AfCFTA in a way that promotes common interests and approaches to investment in the new green sectors.40

Conclusions: Where to Take Climate Issues and Climate Diplomacy

When it comes to climate diplomacy, Africa’s future will determine Europe’s fate. The role of climate finance and the alignment between development and private finance require European and African policymakers to focus on long-term mutual strategic interests in the political, economic, and trade spheres rather than on short-term risks. Never before has the climate agenda become more pertinent to these issues given that the world is moving into a new era of geopolitical fragmentation, fractured trade regimes, and competitiveness issues in green industrialization.

Climate diplomacy, therefore, remains an important tool for all parties to revitalize the Africa-Europe relationship and bring joint, climate-related actions to the center of the economic transformation of both regions through just energy transitions, interlinkages in trade of critical minerals, and mutual industrialization and manufacturing.

About the Author

Saliem Fakir is the executive director of the African Climate Foundation.

Notes

1 Ursula von der Leyen, “2023 State of the Union Address,” European Commission, September 13, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_23_4426.

2 While much of this essay focuses on the European Union, the principles discussed also apply to individual member states and non-EU members.

3 Colin Coleman, “This Region Will Be Worth $5.6 Trillion Within 5 Years—But Only if It Accelerates Its Policy Reforms,” World Economic Forum, February 11, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/02/africa-global-growth-economics-worldwide-gdp.

4 “The World Bank in Africa: Overview,” World Bank, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview.

5 Hamish McRae, The World in 2050: How to Think About the Future (E-book, Bloomsbury Publishing), 2022.

6 McRae, The World in 2050, 265.

7 “European Union–African Union Summit, 17-18 February 2022,” European Council, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-summit/2022/02/17-18.

8 John J. Stremlau, “African Countries Showed Disunity in UN Votes on Russia: South Africa’s Role Was Pivotal,” The Conversation, April 8, 2022, https://theconversation.com/african-countries-showed-disunity-in-un-votes-on-russia-south-africas-role-was-pivotal-180799.

9 Bonface Orucho, “Africa’s Share of Global Gas Supply Will Double by 2050,” World Economic Forum, February 16, 2023, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/africas-global-gas-supply-double-2050-energy-transition.

10 Alex Barnes, “EU Commission Proposal for Joint Gas Purchasing, Price Caps and Collective Allocation of Gas: An Assessment,” Oxford Institute for Energy Series, December 2022, https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/EU-Commission-proposal-for-joint-gas-purchasing-price-caps-and-collective-allocation-of-gas-an-assessment-NG-176.pdf.

11 Nermina Kulovic, “Germany Striving to Develop Gas Field With Senegal Amid Supply Uncertainties,” Offshore Energy, May 23, 2022, https://www.offshore-energy.biz/germany-striving-to-develop-gas-field-with-senegal-amid-supply-uncertainties.

12 NS Energy Staff Writer, “The Largest Cobalt Reserves in the World by Country,” NS Energy, June 7, 2021, https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/features/largest-cobalt-reserves-country.

13 Zainab Usman and Alexander Csanadi, “How Can African Countries Participate in U.S. Clean Energy Supply Chains?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 2, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/10/02/how-can-african-countries-participate-in-u.s.-clean-energy-supply-chains-pub-90673.

14 “Council and Parliament Strike Provisional Deal to Reinforce the Supply of Critical Raw Materials,” European Council, November 13, 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/11/13/council-and-parliament-strike-provisional-deal-to-reinforce-the-supply-of-critical-raw-materials.

15 “EU Urges European Banks to Step Up Funding for Critical Minerals,” Reuters, January 25, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/eu-urges-european-banks-step-up-funding-critical-minerals-2023-01-25; and Michael Peel and Henry Sanderson, “EU Sounds Alarm on Critical Raw Materials Shortages,” Financial Times, August 31, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/8f153358-810e-42b3-a529-a5a6d0f2077f.

16 “Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want,” African Union, https://au.int/agenda2063/overview.

17 “The African Continental Free Trade Area,” African Union, https://au.int/en/african-continental-free-trade-area.

18 These views were shared by Jonathan Wilkinson, a senior member of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government. See Derek Brower, “Canada Warns US Against Waging ‘Carbon Subsidy War,’” Financial Times, April 2, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/4b102da2-5f3e-4046-8d12-ab9e3ca89332.

19 Amanda Chu, Derek Brower, and Aime Williams, “US Touts Biden Green Subsidies to Lure Clean Tech From Europe,” Financial Times, January 24, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/ca95d8e4-79f4-44bb-9d74-df86809de098.

20 Simon Mundy, “Svein Tore Holsetter: Europe Needs ‘Green’’ Fertiliser as Putin Weaponises Food,” Financial Times, January 26, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/e157d9c2-8386-48ee-820e-93696d90a6d7.

21 Hanna Ziady, “Europe Unveils $270 Billion Response to US Green Subsidies,” CNN, February 1, 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/2023/02/01/business/europe-green-deal-industrial-plan/index.html.

22 “Minerals Security Partnership Convening Supports Robust Supply Chains for Clean Energy Technologies,” Office of the Spokesperson, U.S. Department of State, September 22, 2022, https://www.state.gov/minerals-security-partnership-convening-supports-robust-supply-chains-for-clean-energy-technologies.

23 Eric Olander, “China’s Infrastructure Finance Model Is Changing,” Africa Report, January 14, 2020, https://www.theafricareport.com/22133/chinas-infrastructure-finance-model-is-changing-heres-how.

24 Catherine De Beaurepaire, “EU Seeks to Diversify Critical Raw Material Supply Away From China,” Nikkei Asia, March 17, 2023, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Trade/EU-seeks-to-diversify-critical-raw-material-supply-away-from-China.

25 Eric Onstad, “European Fund for Critical Minerals Projects to Launch Next Year,” Reuters, June 17, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/european-fund-critical-minerals-projects-launch-next-year-2022-06-17.

26 Zainab Usman, Olumide Abimbola, and Imeh Ituen, “What Does the European Green Deal Mean for Africa?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 18, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/10/18/what-does-european-green-deal-mean-for-africa-pub-85570.

27 Deborah Brautigam, The Dragon’s Gift (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-dragons-gift-9780199550227?cc=ie&lang=en&#.

28 Dewei Che and Adams Bodomo, “China and the European Union in Africa: Win–Win-Lose or Win–Win-Win?,” Asia Europe Journal 21 (January 2023): 119–136, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-023-00656-y.

29 “Yemi Osinbajo on the Hypocrisy of Rich Countries’ Climate Policies,” The Economist, May 14, 2022, https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2022/05/14/yemi-osinbajo-on-the-hypocrisy-of-rich-countries-climate-policies.

30 See Debt Relief for Green and Inclusive Recovery, accessible at https://drgr.org, which provides useful ideas and insights on how this challenge can be addressed.

31 Chief Editor, “Zambia and UAE Sign Landmark Agreement for $2 Billion Renewable Energy Investment,” Lusakatimes.com, January 17, 2023, https://www.lusakatimes.com/2023/01/17/zambia-and-uae-sign-landmark-agreement-for-2-billion-renewable-energy-investment-2.

32 “European Union–African Union Summit, 17-18 February 2022,” European Council.

33 Conor M. Savoy and Shannon McKeown, “Future Considerations for the Partnership on Global Infrastructure and Investment,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 29, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/future-considerations-partnership-global-infrastructure-and-investment.

34 Chloé Farand, “Mia Mottley Builds Global Coalition to Make Financial System Fit for Climate Action,” Climate Home News, September 23, 2022, https://www.climatechangenews.com/2022/09/23/mia-mottley-builds-global-coalition-to-make-financial-system-fit-for-climate-action; and David McNair, “Was a Global Financial Summit the Start of a New Bretton Woods?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 28, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/06/28/was-global-financial-summit-start-of-new-bretton-woods-pub-90071.

35 “EU Carbon Border Tariffs Could Knock $16bn Off Africa’s Yearly GDP,” Engineering News, February 15, 2023, https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/eu-carbon-border-tariffs-could-knock-16bn-off-africas-yearly-gdp-2023-02-15.

36 Gita Briel, “African States Should Keep Track of the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism as Implementation Advances,” TRALAC, March 8, 2023, https://www.tralac.org/blog/article/15945-african-states-should-keep-track-of-the-european-union-s-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-as-implementation-advances.html; and Gerber Group, “EU Carbon Border Tax CBAM, a Growing Concern for Africa,” Steel News, February 17, 2023, https://steelnews.biz/eu-carbon-border-tax-cbam-growing-concern-for-africa.

37 The insights shared here are based on the author’s personal work on the South African JETP and those for Senegal and Nigeria.

38 “The United States Releases Signed Memorandum of Understanding With the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia to Strengthen Electric Vehicle Battery Value Chain,” U.S. Department of State, January 18, 2023, https://www.state.gov/the-united-states-releases-signed-memorandum-of-understanding-with-the-democratic-republic-of-congo-and-zambia-to-strengthen-electric-vehicle-battery-value-chain.

39 Raphael J. Heffron, “The Role of Justice in Critical Minerals,” Extractive Industries and Society 7, no. 3 (2020): 855–863. [link?]

40 “Experts Call for Green Trade Under the AfCFTA to Tackle Impacts of Climate Change,” United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, October 1, 2021, https://uneca.org/stories/experts-call-for-green-trade-under-the-afcfta-to-tackle-impacts-of-climate-change; and “Carlos Lopes: Free Trade Area Can Break Old Europe Dependency,” Nordic Africa Institute, May 21, 2019, https://nai.uu.se/news-and-events/news/2019-05-21-carlos-lopes-free-trade-area-can-break-old-europe-dependency.html.

Connection and Creativity: Rethinking the Movement of People in and Between Africa and Europe

In 2019, with the space to think about the strategic long-term interests of Europe, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen started her term by prioritizing the EU’s partnership with Africa. She said,

“I have chosen Africa for my very first visit outside of Europe. I hope my presence at the African Union can send a strong political message, because the African continent and the African Union matter to the European Union.”

While a series of crises—including COVID-19, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the war between Israel and Hamas—have dramatically changed her calculus and that of other European leaders, the underlying facts that led von der Leyen to prioritize Africa remain. The two continents have a common and collective future even though, politically, they may feel farther apart than ever.

There are two ways to look at this; plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Existing inequalities will persist, Europe will continue to look down on Africa as a continent in need of help, or aid, to support its (slow) development. Yet, increasingly, this old—and in many ways colonial—approach is seen by many, particularly in Africa, as past its sell-by date.

If Africa and Europe are to work closely together toward a collective future, the people of Africa and Europe need to also be together: to do business, be connected, meet, trade goods and ideas, learn from each other, and partner as equals. And to do this, people need to be able to move- within, and between, the two continents.

Yet, migration and human mobility remains a fundamental unresolved political challenge standing in the way of better Africa-Europe relations.1 There is simply no hope for a partnership of equals until progress is made to facilitate, rather than deter, the movement of people.

Despite this paramount political necessity, the latest headlines in many European countries, including not only Italy and Sweden but also the UK, suggest that if anything the migration governance agenda is backsliding with little appetite for cooperation among European countries, let alone finding common grounds with African counterparts. Most EU migration deals are in fact a framework to manage asylum and do not really address the broader, and in many ways a much more complex, question, of how the two continents can manage the necessary movement of people to support societal needs.

The EU’s approach not only inhibits the creation of new ties but also impacts how Africans feel about Europe. If Africans are not welcomed in a world where they have options, they will take their intellect, creative energy, and considerable future spending power elsewhere. Until some common ground on migration is found, the issue will continue to poison relations between the two continents.

Contrary to this political narrative, overwhelming evidence points to the benefits that migration brings to migrants and their host communities in terms of economic resilience and increasing incomes of domestic populations. More recent studies add to this, increasingly focusing on both the practical implications and the political barriers standing in the way of a more pragmatic approach to migration policies – notably dissociating migration with permanent citizenship of the host country.2

For some time now research has shown that public attitudes on immigration among the European population is not as negative as one might expect given how prominent anti-immigration policies continue to be on the political agenda in several countries. In France, for example, positive sentiments toward migrants have surpassed negative sentiments since 2016, the year of the EU’s so-called migration crisis.3 In 2018, 63 percent of Swedes reported that immigrants make the country a better place to live.4 In Spain less of the population saw immigration as a problem (20 percent) than an opportunity (29 percent) according to survey data in 2021.5

Given this apparent conundrum, it has proven hard to develop policy propositions and political narratives to make the most of these positive attitudes that Europeans hold toward refugees and other migrants.

However, new analysis drawing on historical data is beginning to shed some light on this: European citizens’ positive views of migration could be a reaction to nationalist and far-right electoral successes, in what is known as a “reverse backlash effect.” For example, immigration attitudes improved following the Brexit referendum in the UK and former president Donald Trump’s 2016 election in the United States. This emerging body of evidence suggests that pro-immigration reforms do not necessarily lead to increases in populist voting.6

There is no easy way to interpret this evidence nor point to a policy solution to this apparent paradox. But a mid- to long-term view of how Europeans think and feel about immigration, and what is likely to influence these views, reveals that populists are not likely to succeed. Those with progressive views of human mobility are actually winning, even though it may not feel that way. Or at least not yet.7

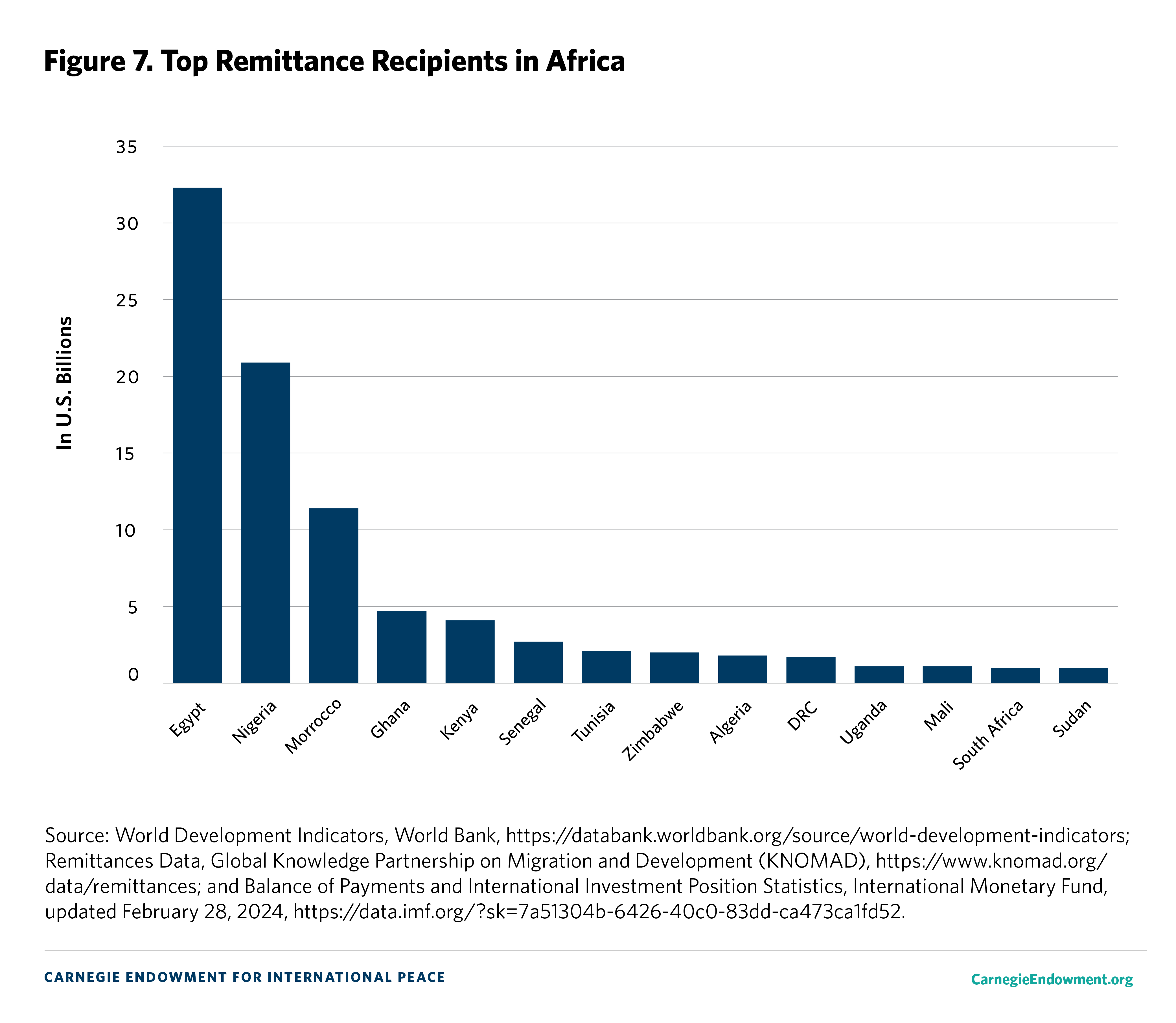

Another key area of evidence concerns the economic benefits of migration. There is ample evidence that moving across borders can bring benefits to those who move in terms of increased income and expanded opportunities;8 those who stay in the sending country via remittance and other nonmonetary benefits, like knowledge transfers; and host communities, as immigrants tend to increase the fiscal balance of the countries where they live, expand opportunities, and increase entrepreneurialism.9 The economic benefits for individuals who move from a developed to an advanced economy and work for minimum wage are on average 334 percent higher than if the individual did not move and instead participated in an economic development program.10

Yet this evidence on the economic benefits of migration is not cutting through to public opinion and has at times contributed to a sense of division between those who benefit from immigration, including the urban elites and potential migrants themselves, and those who feel excluded, such as workers on low income or in deprived areas with poor service provisions and limited employment opportunities.

With such a rational argument for the movement of people, but such a difficult political environment in which to craft and present a new message, the time is ripe for a different way of thinking about the reality of human mobility.

The World Bank’s 2023 World Development Report tried to close this gap and find a pragmatic common ground: a “match and motive” matrix that focuses on how closely migrants’ skills and attributes match the needs of destination countries and what motives underlie their movements. This approach enables policymakers to distinguish between different types of movements, minimize the causes of distressed movements, and maximize the net gains when people bring skills and labor to a new location.11

This kind of pragmatism is needed in the Africa-Europe relations, not least because of the demographic trends. Europe is aging rapidly, which is creating a fiscal time bomb that is increasingly recognized by financial markets. In 2023, Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch warned that worsening demographics are already hitting governments’ credit ratings because of the impacts of higher pensions and healthcare costs.12

As Dietmar Hornung, associate managing director at Moody’s Investors Services, told the Financial Times, “In the past, demographics were a medium- to long-term consideration. . . . Now, the future is with us and already hitting sovereign credit profiles.”

Africa has labor in abundance, as a result of its stage of the demographic cycle. By 2050, it will add 796 million people to the labor force, by which time, Europe’s labor force will have declined by 156 million.13

What would a pragmatic approach to the movement of people look like? We have a proposal.

Here, language really matters. When the media or academics use phrases like “fortress Europe,” they suggest that Europe is trying to protect something dear from attack.

Our proposal involves moving beyond both the defensive language of border protection and the reactive approach that involves responding once the negative narrative has already been set. Instead, we are embracing the idea of spaces and places of connection and creativity and suggesting that policymakers design policies and practices to facilitate these spaces and the movement between places.

The literature on spatial clustering supports the idea that new industries and innovations that create changes in industrial structures are rooted in a specific space and time before being disbursed much more widely.14 This is far from a new idea. Going back to Irish scientist Robert Boyle’s performative lectures at the Royal Society in London in the 17th Century, to the innovation of Silicon Valley, human progress is rooted in spaces and places. Spatial proximity creates ecosystems of learning, innovation and growth. 15

So, the temporary movement of people between places to enable these spaces of connection and creativity could be supported and its potential economic benefits tested, since there are clearly political, social, and creative benefits to doing so.

To change the old, tired paradigm of Africa-Europe migration, we propose shifts in three key areas:

- the narrative defining what migration is about,

- the policies and tools that can turn these changes into reality, and

- the places people move to and the leaders embracing this movement.

Investing in Creativity

Moving between places and across borders is much more than just crossing them. It is a journey of ideas, talent, and cultures. Yet this is so often missing in Africa-Europe relations: a narrative that considers the movement of talent and ideas, not just bodies (or brains), across and between the two continents.

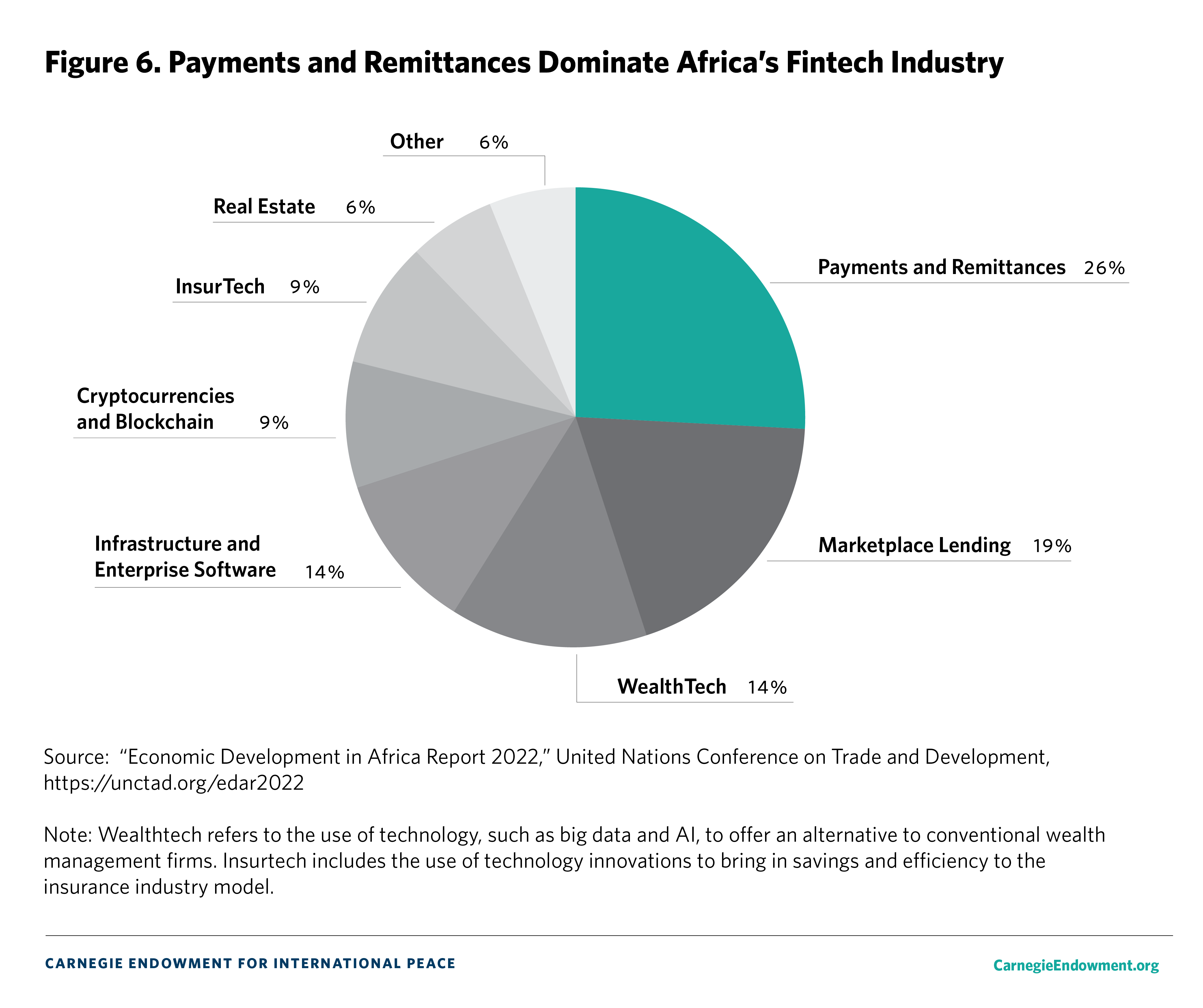

Culture and creativity are areas where Africa and Europe present a unique added value to each other, with the potential for investment to make a real difference to economic and social development.16 The so-called old continent is revered and respected around the world for its culture, art, design and history—including in the relatively recent boom in European luxury goods.17And Africa has demonstrated the value of its cultural dynamism in the areas of fashion, food, and music.

In 2022, sub-Saharan Africa had the fastest-growing music market in the world, according to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry.18 Afrobeats, for example, has become a global cultural export with artists like Burnaboy and Wizkid regularly selling out Madison Square Gardens. Afrobeats manager and CEO of Mavin Records, Don Jazzy, has spoken of the challenges he has faced in gaining visas to Europe for his artists despite the significant cultural and economic capital they bring.19 They are young, highly creative artists with massive followings and huge potential. But they are also young African men with few financial assets and are therefore considered a risk under current visa rules.

African fashion was identified by the Economist as one of the five global trends to watch in 2022.20 Cultural exchanges (featured in figure 2), highlight the vibrancy of the sector. A major exhibition called Africa Fashion opened in July 2022 at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, “exploring the vitality and global impact of a fashion scene as dynamic and varied as the continent itself,” where cultural exchange was a key outcome.21 African designers are hot tickets at London, Milan, and Paris fashion weeks, and Chanel chose Dakar as the setting for its latest fashion show.22

Beyond catwalks, creative sectors are increasingly seen as key to fostering local economic development, especially in cities.23 African and European cities collaborate to create opportunities for city-based creatives to connect, exchange practices and ideas, co-create, and make the most of the business opportunities that these collaborations may lead to. As with the Afrobeats example, these initiatives are severely hampered by the ability of African creatives to obtain visitor and business visas to travel to Europe.

Figure 2. Freetown based fashion models and designers on a cultural exchange in London. Photo credit: Sama Kai. London, September 2022

African designers in more elite cultural spaces face the same challenge. The 2023 Architecture Biennale was curated by Scottish-Ghanaian architect Lesley Lokko.24 Yet some of Lokko’s collaborators were denied visas to travel to Venice.25 The Italian Embassy in Accra claimed there were reasonable doubts on their “intention to leave the territory, or state, before the expiry of [their] visa.” In other words, they cannot be trusted to just want to visit as guests of a high profile international cultural event. Lokko went on to win the Royal Institute of British Architect’s Royal Gold Medal in 2024.26

With the 2024 Venice Art Biennale titled ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ aimed at celebrating the immense contribution of diasporas and migrants to the arts, there is an urgent need to match the narrative with concrete policy change to finally unleash the largely untapped potential of African talent.

Reforming Visa Regimes27

This leads to the second shift: what would it take to make the most of the potential of African, often young, creative talent in ways that could benefit the arts and culture sectors in both continents? A reform of the temporary visa system to proactively promote spaces and creation and collaboration.28

Visas matter because visiting, for work or leisure, is part of day-to-day life: going to places for short visits, temporary work, or education is not only often necessary, but it is also key to the human experience, for pleasure and happiness, to meet colleagues, friends, and family, to learn, and to develop new skills and ideas. Visa regimes are also vital components of trade agreements and are critical in some key sectors of modern economies, from culture, the arts, and tourism to tertiary education and research.29

Schengen countries (EU member states that have agreed to a passport-free zone) have agreed on a common, short-stay visa regime that allows third-country nationals to travel to any member of the Schengen Area for up to ninety days for tourism or business purposes. This agreement provides some common standards to the application process as well as precious data to better understand what happens to visa applications.

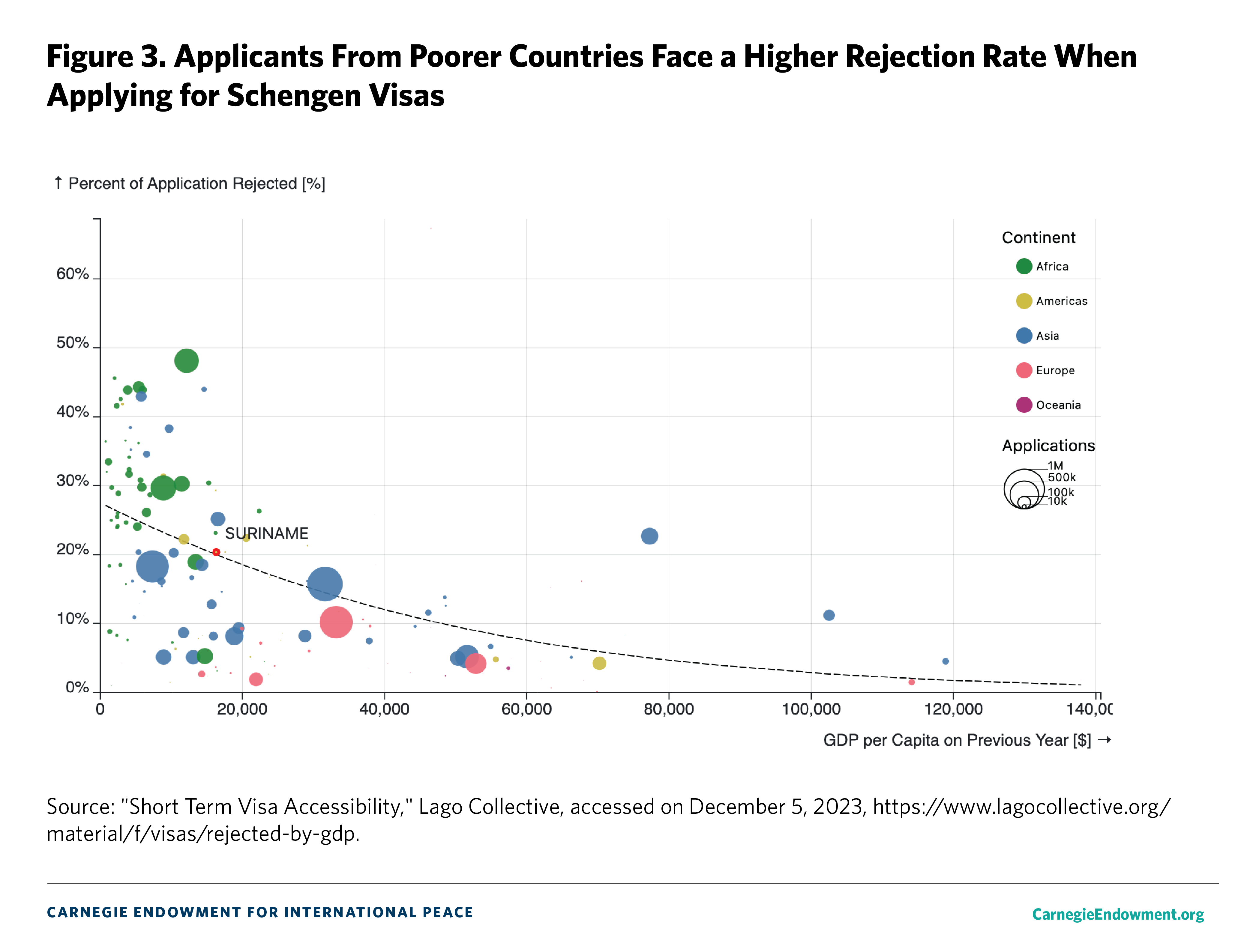

But the success rate of a Schengen visa application tends to depends on the GDP per capita of the country where the application is lodged. The poorer the country, the higher the rejection rate (see figure 3).30 Analysis shows the cost borne by applicants whose visas are rejected is around €130 million a year; such costs are nonrefundable.

The rejection rate is especially high for African countries, yet most Schengen country nationals (who are European) would still be able to obtain a visa on arrival in most of the African countries where these rejected applications are lodged. Furthermore, the ease of access to African e-visas has increased dramatically since 2016.31

If European and African policymakers are committed to better and more equal Africa-Europe relations, they need to fix visa regimes32 not only because of their deeply unequal nature and the unfair deal for Africa but also because as they stand, they pose major problems for Europe. Crucially, this will create opportunities and growth on both sides of the Mediterranean.

Policy change is however not enough unless those who can turn these changes into practice have the power and resources to act. This leads to a third shift.

Shifting Power to Cities

People move to cities. By 2050, two-thirds of the world population will live in cities. Eight of the twenty fast-growing cities are located on the continent.33

In the same way that the battle for climate change will be won or lost in urban areas, the opportunities and challenges that migration brings must be addressed in cities.

Many African and European mayors know this and joined forces to create the Mayors’ Dialogue as a political platform to act together, in a partnership of equals. The mayors of Freetown (Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr) and Milan (Giuseppe Sala) led the initiative (see figure 4), and more than twenty cities were represented, from Lisbon to Amsterdam, Accra to Kigali and Abidjan. The aim is to build on the connections rather than the differences between the cities, countries, and continents. The mayors’ focus is very much on practical innovations, local solutions, and learning from each other’s experiences.34

Figure 4. Mayors Sala (Milan) and Aki-Sawyerr (Freetown) at the Mayor’s Dialogue discussing common challenges and solutions. Photo Credit: Mia Isabella Photography

Figure 5. Fashion designers from Freetown on the catwalk of Durban Fashion Week, September 2023 Photo: Envizage Concepts.

Creatives thrive in cities, and cities move, change, and grow with the innovative minds they host. Urban landscapes are shaped by creative practices rooted in local communities, which can lead to transformative urban agendas with increasing attention to sustainability and inclusion. This happens because of people, collaboration, and experimentation, at the individual and institutional levels, often across borders. The movement of people, ideas, and talents between cities is essential to make the most of the opportunities and potential that creative sectors bring to local economic development.

Some examples are already underway: For one, example, Durban, Freetown, London, and Milan (featured in figures 2 and 5) collaborate to support exchanges between city creatives, involving diasporas and using fashion and design weeks/events to anchor the collaboration.35 The potential to support city mayors in creating concrete opportunities for exchanges and collaboration between designers, access to training and skills development, and connecting manufacturers and investors is immense.

Here’s where demographic shifts are again relevant. With Europe’s aging population, Africa’s increasingly urban youth boom is likely to be a source of youthful creative energy for a generation. Specific economic support to build creative and cultural hubs around fashion, film, music, and food—accompanied by supportive visa policies to promote these spaces of connection—could be the spaces that create new narratives, cultural movements, and economic sectors for Europe and Africa.

Putting power and financial resources in the hands of city mayors, who are less likely to have the political constraints of national leaders and instead have direct incentives to create opportunities for all urban residents, will lead to greater opportunities to make these spaces of creativity, human mobility, and talent grow.

These shifts in thinking about human mobility will tell a different tale on the necessity and beauty of the movement of people and culture within and between the two continents: a story of talent, opportunities, trade and economic development, and local action and innovation.

About the Authors

Marta Foresti is the founder of the creative LAGO Collective and a senior visiting fellow at ODI.

David McNair is a nonresident scholar in the Africa Program and the executive director at ONE.org.

Notes

1 Shada Islam, “Fortress Europe Is the ‘Root Cause’ for Strains in EU-Africa Relations,” Brussels International Center, May 11, 2023, https://www.bic-rhr.com/research/fortress-europe-root-cause-strains-eu-africa-relations.

2 Lant Pritchett and Rebekah Smith, Is There a Goldilocks Solution? “Just Right” Promotion of Labor Mobility, Centre for Global Development, 7 November 2016. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/goldilocks-solution-just-right-promotion-labor-mobility

3 Claire Kumar, Kerrie Holloway, Diego Faurès, Public narratives and attitudes towards refugees and other migrants: France country profile, ODI, 5 April 2022. https://odi.org/en/publications/public-narratives-and-attitudes-towards-refugees-and-other-migrants-france-country-profile/

4 Kerrie Holloway, Diego Faurès, Amy Leach, Public narratives and attitudes towards refugees and other migrants: Sweden country profile, ODI, 13 January 2022. https://odi.org/en/publications/public-narratives-and-attitudes-towards-refugees-and-other-migrants-sweden-country-profile/

5 Hearts and minds: How Europeans think and feel about immigration, ODI, https://heartsandminds.odi.digital/index.html

6 Dennison, James & Kustov, Alexander. The Reverse Backlash: How the Success of Populist Radical Right Parties Relates to More Positive Immigration Attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly (2023).

7 John Burn-Murdoch, Progressives are winning the immigration debate — but it doesn’t feel like it, Financial Times, 5 May 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/b743e1fa-f6c1-4d41-a845-e25c8d5fbd91

8 Lant Pritchett and Rebekah Smith, Is There a Goldilocks Solution? “Just Right” Promotion of Labor Mobility, Centre for Global Development, 7 November 2016. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/goldilocks-solution-just-right-promotion-labor-mobility

9 Gemma Hennessey and Jessica Hagen-Zanker, The fiscal impact of immigration: a review of the evidence, ODI, 20 April 2020. https://odi.org/en/publications/the-fiscal-impact-of-immigration-a-review-of-the-evidence/

10 Lant Pritchett and Rebekah Smith, Is There a Goldilocks Solution? “Just Right” Promotion of Labor Mobility, CGD, 7, November 2016. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/goldilocks-solution-just-right-promotion-labor-mobility

11 World Bank. 2023. World Development Report 2023: Migrants, Refugees, and Societies. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1941-4. License: Creative

Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2023

12 Mary McDougall, Ageing populations ‘already hitting’ governments’ credit ratings, Financial Times, 17 May 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/f434c586-db1f-4d81-8b29-989db5c78f72

13 Mayowa Kuyoro, Acha Leke, Olivia White, Jonathan Woetzel, Kartik Jayaram and Kendyll Hicks, Reimagining economic growth in Africa: Turning diversity into opportunity, McKinsey Global Institute. https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/reimagining-economic-growth-in-africa-turning-diversity-into-opportunity#/

14 Sturgeon, Timothy J. “What Really Goes on in Silicon Valley? Spatial Clustering and Dispersal in Modular Production Networks.” Journal of Economic Geography, vol. 3, no. 2, 2003, pp. 199–225. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26160457

15 David Livingstone, Putting Science in its Place: Geographies of Scientific Knowledge, The University of Chicago Press (2003). https://www.asia-europe.uni-heidelberg.de/fileadmin/Documents/Summer_School/Summer_School_2013/Reading_session_I_text.pdf

16 Marta Foresti, Creating our collective future: what the arts and design can do for development, ODI, 24 June 2022. https://odi.org/en/insights/creating-our-collective-future-what-the-arts-and-design-can-do-for-development/

17 Janan Ganesh, Luxury goods: Europe’s joke on the world, Financial Times, 9 June 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/1b68b08c-01bd-487e-b5bc-18b0cfedd462

18 IFPI, Global Music Report: Global Recorded Music Revenues Grew 9% In 2022. 23 March 2023. https://www.ifpi.org/ifpi-global-music-report-global-recorded-music-revenues-grew-9-in-2022/

19 Don Jazzy, ‘X’ post, 24 July 2013. https://x.com/DONJAZZY/status/360096987548360704?s=20

20 Georgia Banjo, African fashion designers will be in the spotlight, The Economist, 8th November 2021. https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2021/11/08/african-fashion-designers-will-be-in-the-spotlight

21 Lauren Cochrane, V&A to display its first African fashion exhibition, The Guardian, Tue 28 Jun 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/jun/28/v-and-a-africa-fashion-exhibition-victoria-and-albert-museum. V&A, African Fashion. https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/africa-fashion

22 Luke Leitch, Chanel Pre-Fall 2023, Vogue, 8 December 2022. https://www.vogue.com/fashion-shows/pre-fall-2023/chanel

23 World Bank, Cities, Culture, Creativity: Leveraging Culture & Creativity for Sustainable Urban Development & Inclusive Growth, 21 May 2021. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/publication/cities-culture-creativity

24 The 18th International Architecture Exhibition, titled The Laboratory of the Future, 4 August 2023. https://www.labiennale.org/en/news/biennale-architettura-2023-laboratory-future-0