This essay is part of a series of articles, edited by Stewart Patrick, emerging from the Carnegie Working Group on Reimagining Global Economic Governance.

“Growth” is a term used by economists aiming for expanded economic activity: an increase in investment, employment, goods, and services. Conversely, it is used in a pejorative sense by environmental campaigners convinced that the endless expansion of economic activity in a world of finite resources is unsustainable. Its antonym, “degrowth,” is deployed instead, as in The Future Is Degrowth: A Guide to a World beyond Capitalism. The use and evolution of “growth,” and its link to GDP, represent an important stage in the development of today’s system of global economic governance, based as it is on expectations of continuous “growth” facilitated by financial deregulation and capital mobility. Such “growth” in the context of financialized capitalism has led to ecological, social, and economic imbalances that threaten systemic failure.

The global liquidity flows that are a consequence of the financial system’s development are channeled in large part through nonbank financial institutions, also known as “shadow banks.” According to the Financial Stability Board, the total value of financial assets held by shadow banks in 2022 amounted to $217 trillion—more than double global income (GDP). By design, these institutions operate beyond the reach of regulatory democracy, even though they are tethered to the world’s central banks. Their activities impact economic policy making at the level of the state and pose systemic risks to the world economy.

To re-imagine global economic governance, we need to go back in time and assess the emergence of a system of global economic “nongovernance,” or “a nonsystem,” to quote José Antonio Ocampo. One that has led to the creation of the shadow banking system—and to destabilizing global financial and economic imbalances.

The Origins of “Growth” and Deregulation

The story starts with British economist John Maynard Keynes. Back in the 1930s, Keynes played a far greater role in the creation and construction of the UK’s (and ultimately the world’s) national accounts than is usually recognized. He did so not for the purpose of accounting, but to assess the existing level of income against the potential level of income under certain policy conditions.

The value of what was then known as the “national income,” and which came to be defined by Simon Kuznets as “GDP,” was of minor interest to Keynes. As Geoff Tily explains, Keynes regarded the development of such accounting as a means to an end, not an end in its own right. “The national accounts were developed to support policy: to resolve the unemployment crisis of the Great Depression and to aid the deployment of national resources to their fullest possible extent for the conduct of the Second World War.” It is important to recognize, Tily continues, that

these theoretical and practical initiatives were aimed at the level of activity—at the increased and then full employment of resources and the full extent of national production—rather than the growth of activity. At this stage there was no notion on the part of policymakers that the level of activity might be encouraged to grow in any systematic or uniform way from year to year; the intention was achieving one-off level shifts. There can be no doubt that they were successful in this aim, and in sustaining these gains as the post-war golden age. (Emphasis added).

The “Growth” Revolution

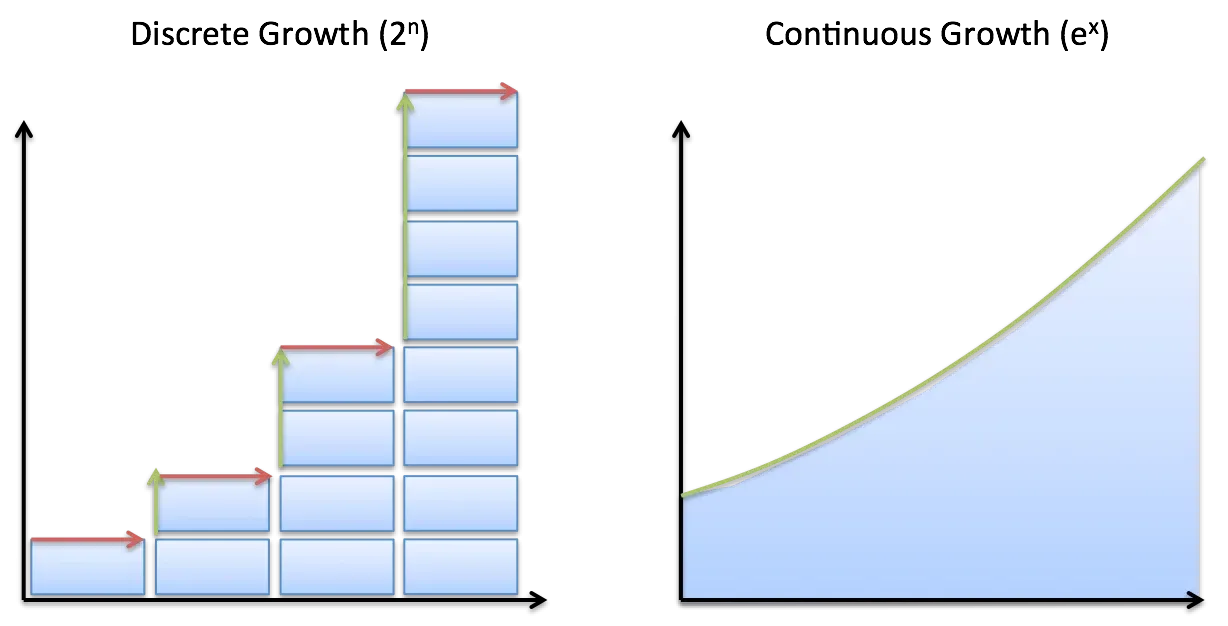

This approach to national accounts changed radically in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In the United Kingdom, various professional economists—not least Sir Samuel Brittan, prominent columnist at the Financial Times—championed a new concept of continuous “growth” and defined themselves as “the growthmen.” It was an approach that changed the character of policy over the postwar age. Abandoning the aim of fixing the level of employment and output to sustainable levels, governments would set a systematic and improbable target: to chase growth. Nobody seems to have paused to consider whether growth—derived as the rate of change of a continuous function—was a meaningful or valid way to interpret changes in the size of economies over time, writes Tily.

Illustration source: “Better Explained”

In parallel, economic policy increasingly emphasized supply-side approaches, and hence a practical commitment to increased deregulation of economic activity. This is exemplified by the Council of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) adopting on September 12, 1961, a “Code for Liberalisation of Capital Movements.” This code, a framework for the progressive removal of barriers to cross-border capital flows, presumably was designed to enable what Tily calls the “ludicrous ambition of rapid and relentless growth, regardless of the extent of capacity in the labour market.”

In October 1961, the OECD held a conference on “Economic Growth and Investment in Education” at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC. Encouraged by “classical” economists and discouraged by what (compared to today’s standards) were high yet sustainable levels of economic activity, the OECD proposed to turbo-charge the UK’s and other economies. At the time, the United Kingdom was in the happy position of providing full employment. In the words of then prime minister Harold Macmillan, Britons had “never had it so good.” On November 17, 1961, the OECD agreed to a 50 percent growth target for the UK for 1960 to 1970. The OECD target was equivalent to 4.1 percent per year. At the time, the British unemployment rate was 1.2 percent.

The result of this overly ambitious goal-setting was entirely predictable—an era of rampant inflation in the 1970s, followed by periods of financial excess and recurring crises. The blame for this inflation has since been laid squarely, and unfairly, on the shoulders of Keynes and on the labor movement. In fact, the attempt to achieve a wildly implausible growth target in conditions of near full employment led to the undoing of Keynes’s legacy: the “golden age” of capitalism from 1945 to 1971. Above all, it led to the dismantling of the system of managed global economic governance established at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944.

On the Question of Global Economic Governance

In the introduction to their book, Who Governs the Globe?, Deborah Avant, Martha Finnemore, and Susan Sell argue that the technical term “governance” obscures the role played by the world’s actual governors. Such abstractions absolve powerful individuals and institutions, including nonstate actors, of responsibility. Furthermore, as they explain

State-centric frameworks do not capture . . . the actual governance that goes on in the world today. Only a small fraction of global governance activity involves state representatives negotiating only with each other. . . . Globalization, deregulation, privatization and technological change have empowered non-state actors. Much of the literature on global governance equates it, implicitly or explicitly with the provision of global public goods. . . . [In fact,] governance outcomes are frequently disconnected from both the public and the good. Global inaction on climate change, access to HIV/AIDS and COVID vaccines are prominent examples. The 2007–09 global financial meltdown is another.

Nongovernance by states of the global economy has led to an international economic system that in effect is governed by private and not public (that is, democratic) authority—even as public taxpayer-backed institutions play a role in subsidizing, derisking, and bailing out private financial institutions.

Thanks to capital mobility, private actors in the international financial system exercise undue influence over policies vital to the economic stability of states, including exchange rates; interest rates; and global flows of investment, capital, and trade. This loss of public authority over both the global and domestic economies has led to disillusionment with democracy. Above all, it has generated obscene levels of inequality within and between states. This inequality, as Michael Pettis and Matthew C. Klein illustrate in their book, Trade Wars Are Class Wars, has helped create trade and capital account imbalances between states.

The global economic model that emerged from the growth revolution of the 1960s orients economies away from the domestic sphere, toward deregulated international capital markets and exports. The export orientation of economies like Germany and China boosts the income of the 1 percent: the owners and shareholders of export-oriented corporations. The incomes of the remaining 99 percent—the wages of workers in the domestic economy—are depressed. The British Resolution Foundation calculates that after fifteen years of stagnation, average earnings in the United Kingdom are £230 below the trend before the global financial crisis of 2007–2009. The Trades Union Congress argues that workers have endured the longest pay squeeze since the Napoleonic wars of the early nineteenth century.

However, the challenge is this: the top 1 percent of wealth holders do not spend all they earn. There are limits to the number of superyachts, private jets, and expansive estates they can buy. In contrast, the 99 percent spend all their income—using it to keep the roof over their heads, buy food, maintain their health, and send their children to university. However, as incomes have fallen in real terms, populations have come to lack the purchasing power needed to buy all that is produced by the export-oriented economy. Far from society’s purchasing power chasing too few goods and services, there are in aggregate terms too many goods and services chasing too little purchasing power. This imbalance has led to high levels of private debt, as the 99 percent borrow money for housing, healthcare, and food at the same time as firms (which cannot sell all they produce) borrow to compensate for falling sales.

The consequences are the reverse of most conventional economic commentary: overproduction, high levels of private debt, and falling incomes. Experience has shown that all of these elements lead to global financial crises.

What Is to Be Done?

Keynes’s policies for stable levels of production and employment required a global economic system that sustained, rather than opposed, domestic policymaking. As he prepared the British Treasury for the Bretton Woods conference, he explained to the House of Lords in 1944 that his “main task for the last twenty years” had been to ensure that

in [the] future, the external value of sterling shall conform to its internal value as set by our own domestic policies, and not the other way round. Secondly, we intend to retain control of our domestic rate of interest, so that we can keep it as low as suits our own purposes, without interference from the ebb and flow of international capital movements or flights of hot money. Thirdly, whilst we intend to prevent inflation at home, we will not accept deflation at the dictate of influences from outside. In other words, we abjure the instruments of bank rate and credit contraction operating through the increase of unemployment as a means of forcing our domestic economy into line with external factors. (Emphasis added.)

Keynes assumed that a monetary system that primarily served the interests of finance and wealth was opposed to stable levels of production and employment at home, and ultimately to balanced trading and financial relationships between states. Given today’s advanced scientific understanding of the earth’s finite resources, it is evident that a global economic system based on perfectly compounded interest and capital accumulation also stands in opposition to a stable climate and ecosystem. Belief in the viability and continuation of such a system is utopian. Given climate breakdown, societies facing extreme weather conditions and the resulting crop and energy failures will have to urgently transform the global “nonsystem” in order to stabilize domestic economies.

Global economic stability will require the restoration of balance to the international trading system and the reorientation of economies away from the global financial system and toward domestic economic interests, in particular those of the majority within economies: the 99 percent. In other words, the global economy needs to be restructured away from the interests of globalized wealth to the interests of workers in the domestic economy. We must again build an economy for work—especially the work of restoring balance to the ecosystem—and not wealth.

If faith in democracy is to be retained and if authoritarian forces are to be suppressed, societies must cooperate to help restore public, democratic, and accountable authority over the global and domestic economy. This transformation can be achieved only if the international community works in solidarity to restrain and manage global capital and trade flows. To do so will require a new form of global economic governance, based on international cooperation and coordination—and on balanced and sustainable economic activity.

One of the ways in which international solidarity can be fostered is by dismantling the financial system of unfettered capital mobility, based on a single, hegemonic reserve currency—a system as harmful to citizens of the hegemon as it is to many other states, as Michael Pettis argues. Fundamental to any move to “a world beyond capitalism” must be the abandonment of the system that turbo-charged globalization in the 1960s: “growth” derived as the rate of change of a continuous function.

Ann Pettifor is a political economist, author, and public speaker. Her latest book, The Case for the Green New Deal, was published in hardback by Verso in 2019. Known for her work on sovereign debt and the international financial architecture, she led a campaign, Jubilee 2000, which resulted in the cancellation of approximately $100 billion of debt owed by the poorest countries. She is Director of PRIME (Policy Research in Macroeconomics) a network of economists that promote Keynes’s monetary theory and policies, and that focus on the role of the finance sector in the economy.

.jpg)