Introduction

Although all of Africa contributes less than 4 percent to global greenhouse gases annually, many African countries are especially vulnerable to extreme weather events and are unable to adapt to long-term changes in the climate.1 African countries experience an average of 5 to 15 percent GDP loss per year due to climate change.2 But when the countries who are party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) come together at their annual summit (the Conference of Parties, or COP) to discuss how to mitigate and adapt to the negative impacts of climate change, who speaks for the continent of Africa?

While COP has been criticized as ineffective or for so-called greenwashing,3 it remains the primary way for countries to negotiate their climate priorities internationally. Fundamentally, outcomes from COP reflect the priorities and efficacy of the various country and regional negotiators. Thus, to understand the outcomes, it is crucial to understand the structure of the negotiators themselves.

Since the first COP in 1995, African governments have negotiated both as individual states and as a continent through the Africa Group bloc. This coalition allows smaller, less-developed states to utilize the technical, economic, and political capital of African powerhouses like Nigeria, Egypt, and South Africa. In addition, African countries often belong to many different negotiating blocs to leverage their power in numbers and increase their influence at COP. Africa’s delegations have grown faster than delegations from any other region, using technical and policy advice from experts and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Many, if not all, of the national delegations in Africa are partially composed of members of civil society, primarily youth groups, media and journalists, and environmental NGOs.

But a large delegation from a country or region to COP does not necessarily translate directly into favorable outcomes. Like other groups of developing countries, African representatives often struggle to leverage their voices at COP to influence the developed countries, and the Global North continues to postpone its commitments to the Global South.

While the Africa Group is increasing its presence and voice at COP, it is unclear whether this increased visibility will lead to better climate outcomes for Africa. And the complex arrangement of negotiating blocs and alliances has created trade-offs between power through membership and internal conflicts of interest—the priorities of small island nations like Mauritius are often very different from those of large landlocked countries like Chad or the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The diversity of the African continent’s biomes, economies, and languages can be a disadvantage in the climate negotiations because of conflicting interests, personalities, and power struggles.

Lastly, international (in other words, non-African) donors often provide funding and support to African actors interacting at COP. This practice helps to increase the capacity and resources available to African actors, but some COP participants have raised concerns that international support could influence the priorities of these actors.

This article maps out the most important African actors at the UN climate negotiations and explores some of the internal tensions and trade-offs across the continent.

African Delegations by Size

Delegations to COP are generally led by heads of state, ministers, or, in some cases, official senior advisers to heads of state. But they also include civil society, such as representatives from nonprofits, scientists and researchers, university professors and students, business leaders, and bankers.

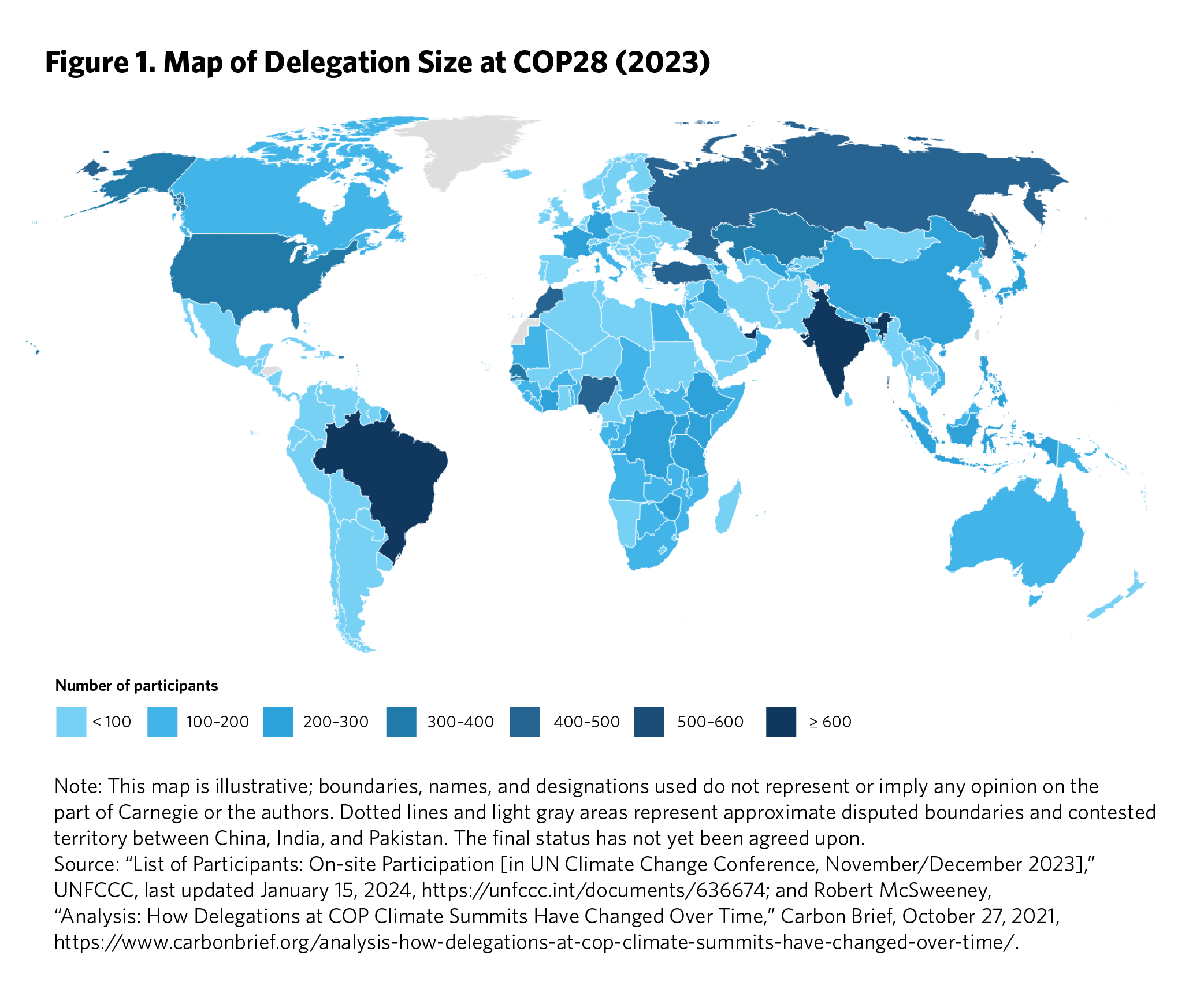

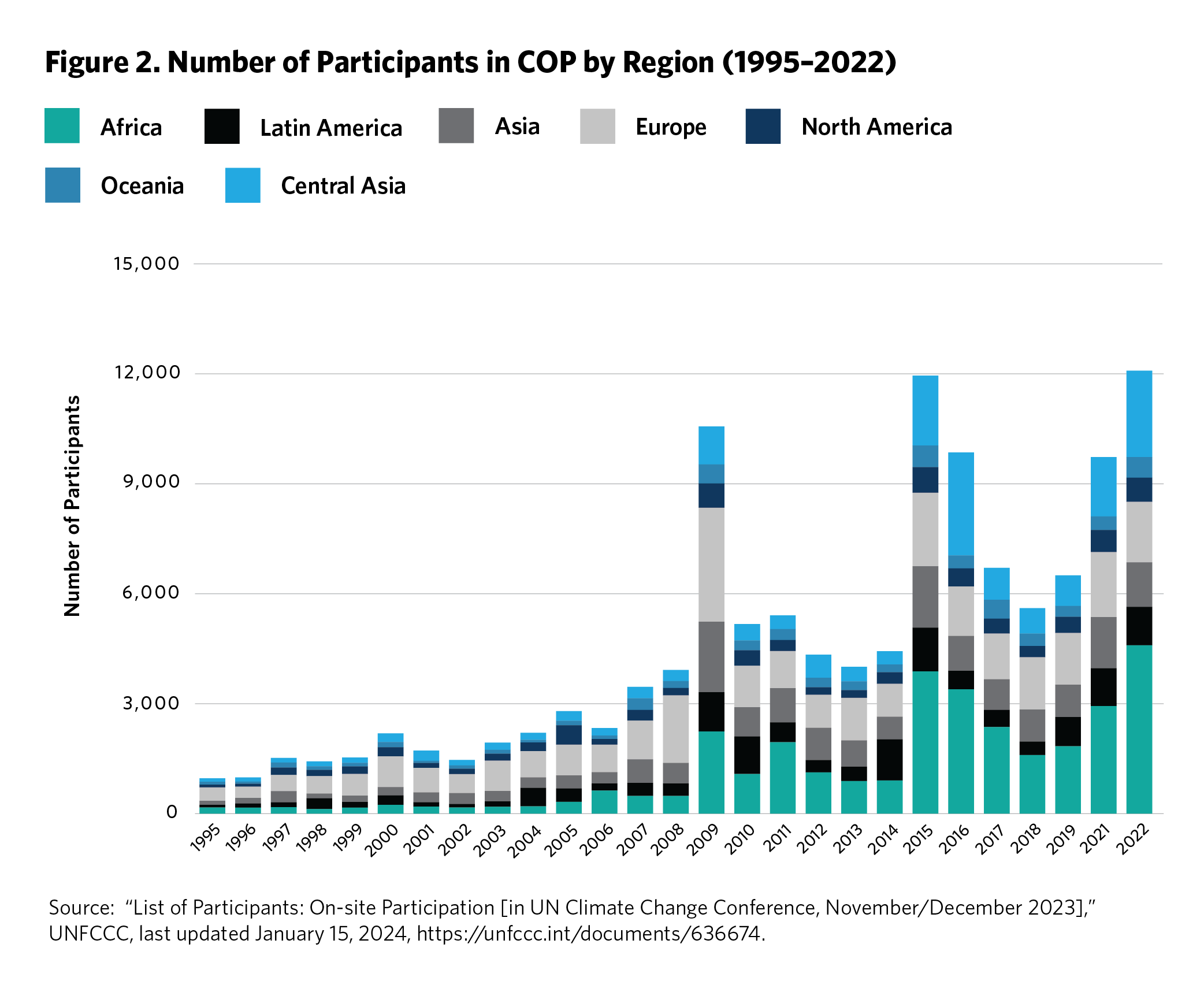

Delegation size by country has varied significantly (see figure 1 for an example from 2022). But official government delegations to COP have increased in size dramatically, especially those from Africa (see figure 2). Over the past ten years, the total number of delegates from Africa has increased 325 percent, outpacing both the European Union (by 88 percent) and the global average (by 217 percent). Figure 2 also shows that the Group of 77 (or G77, a coalition of 135 developing countries) and the Africa Group are numerically larger than all other negotiating groups and have outpaced other groups in increasing their delegation size.4

In general, delegation size has increased since 1995. However, there were significant spikes in 2009 and 2015, when landmark agreements were adopted in Copenhagen and Paris. Intersessional meetings throughout the year and publicized meetings between world leaders (such as the meetings between then U.S. president Barack Obama and Chinese Premier Xi Jinping before COP21 in 2015) can tip off countries, civil society, and the media that important decisions will be made at that year’s conference. This can build momentum and, subsequently, prompt a larger turnout. COP22 (in 2016) and COP27 (in 2022) were also highly attended, in part because attendees sought to follow up on the implementation of agreements made in the previous years.

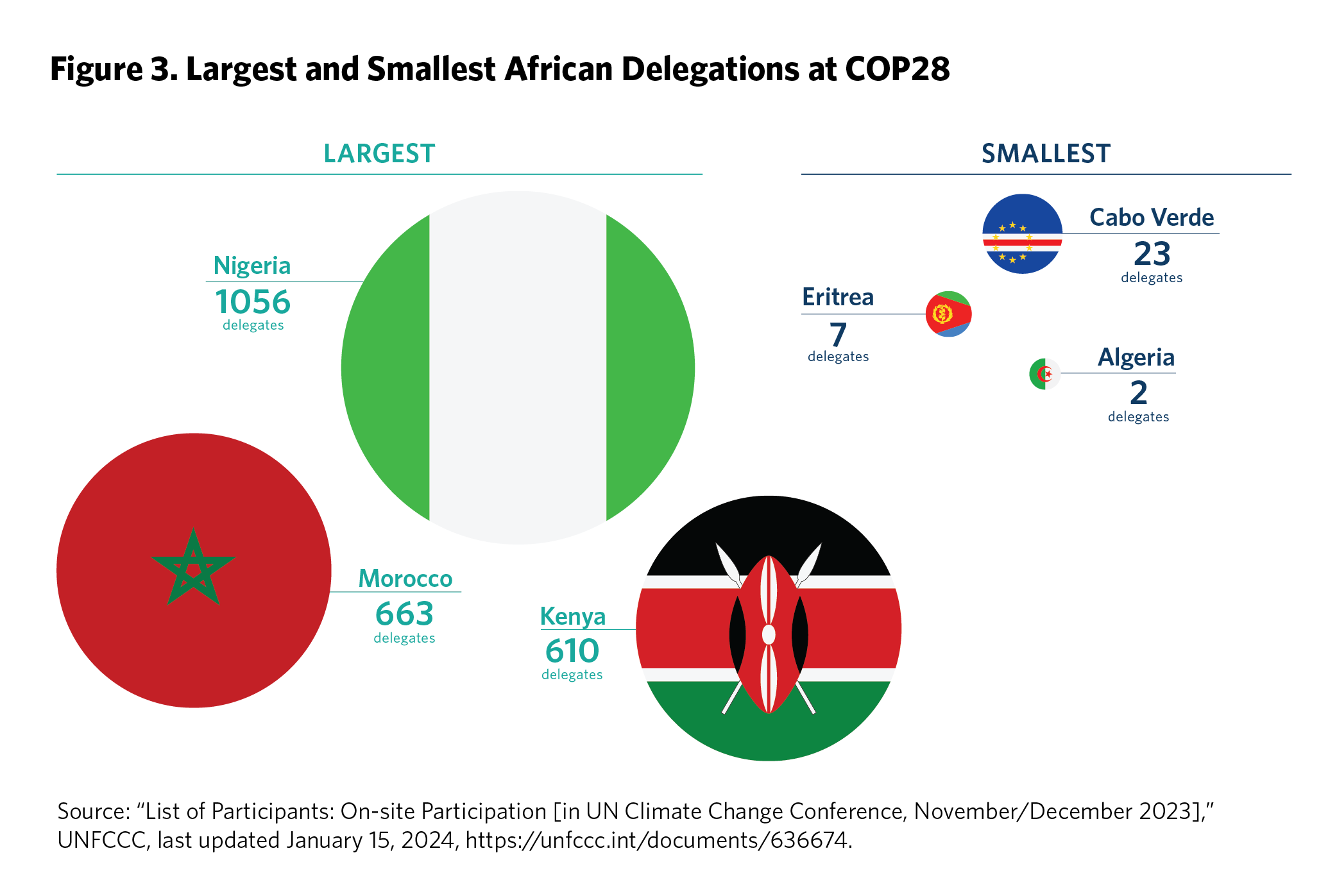

Within Africa, the size of delegations varies drastically (see figure 3). In 2022, the largest delegation from Africa was Kenya (348 delegates), followed by the DRC (303) and Chad (224). The smallest delegations from Africa were Eritrea (6), São Tomé and Príncipe (8), and Mauritius (9).

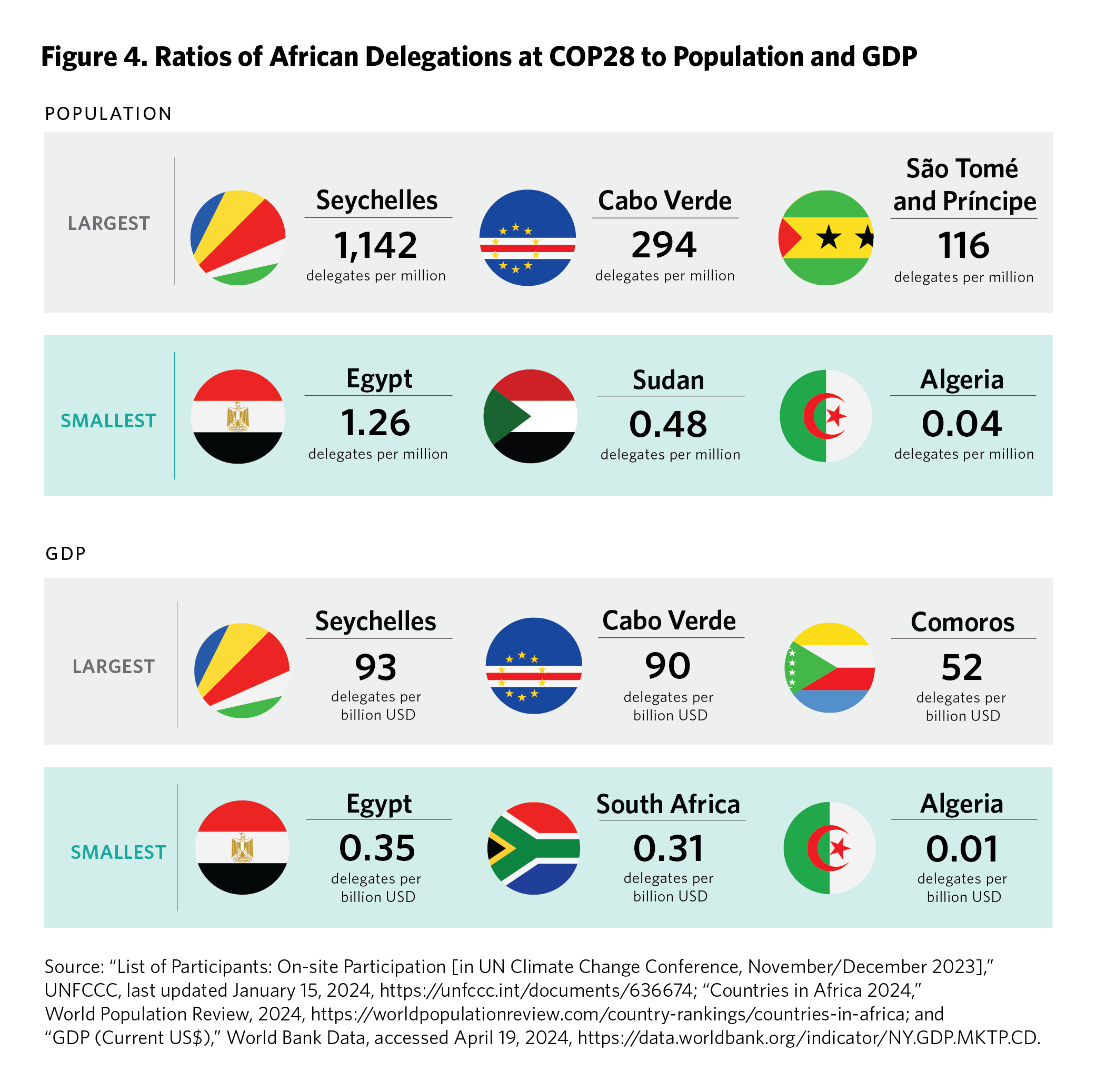

Notably, the largest delegations were not from the countries with the largest economies or populations (see figure 4). While small island states typically send the smallest delegations numerically, they are quite large relative to those countries’ populations. Kenya, Nigeria, and Morocco sent the largest delegations to COP28, but they were not large in proportion to the countries’ GDP or population.

The variable delegation sizes suggest that some of the least-developed countries believe it is in their interest to send very large delegations to COP, perhaps for reasons of prestige, patronage, or business opportunities. However, in informal conversations, some participants at COP27 mentioned that small countries also view the conference as a networking opportunity, where they can build relationships with other countries, learn about adaptation methods, or seek advice about how to certify their national banks to qualify for adaptation and mitigation funding from the UN.

Regional Groups, Negotiating Blocs, and Alliances

Participating in official party groups allows a country to combine expert capacity, build common positions, and rely on power in numbers. There are at least fourteen negotiating blocs, alliances, or party groups in the UNFCCC, and most countries are members of multiple groups.5 The key challenge to having their voices heard, therefore, is not one of representation but one of negotiating strategies and tactics. It remains unclear whether countries with smaller delegations risk stretching their capacity thin by participating in too many groups or, by contrast, whether greater participation increases their chances of having their voices heard in the negotiations. Comoros and Mali, for example, are each part of seven groups, the highest number for any country from Africa.

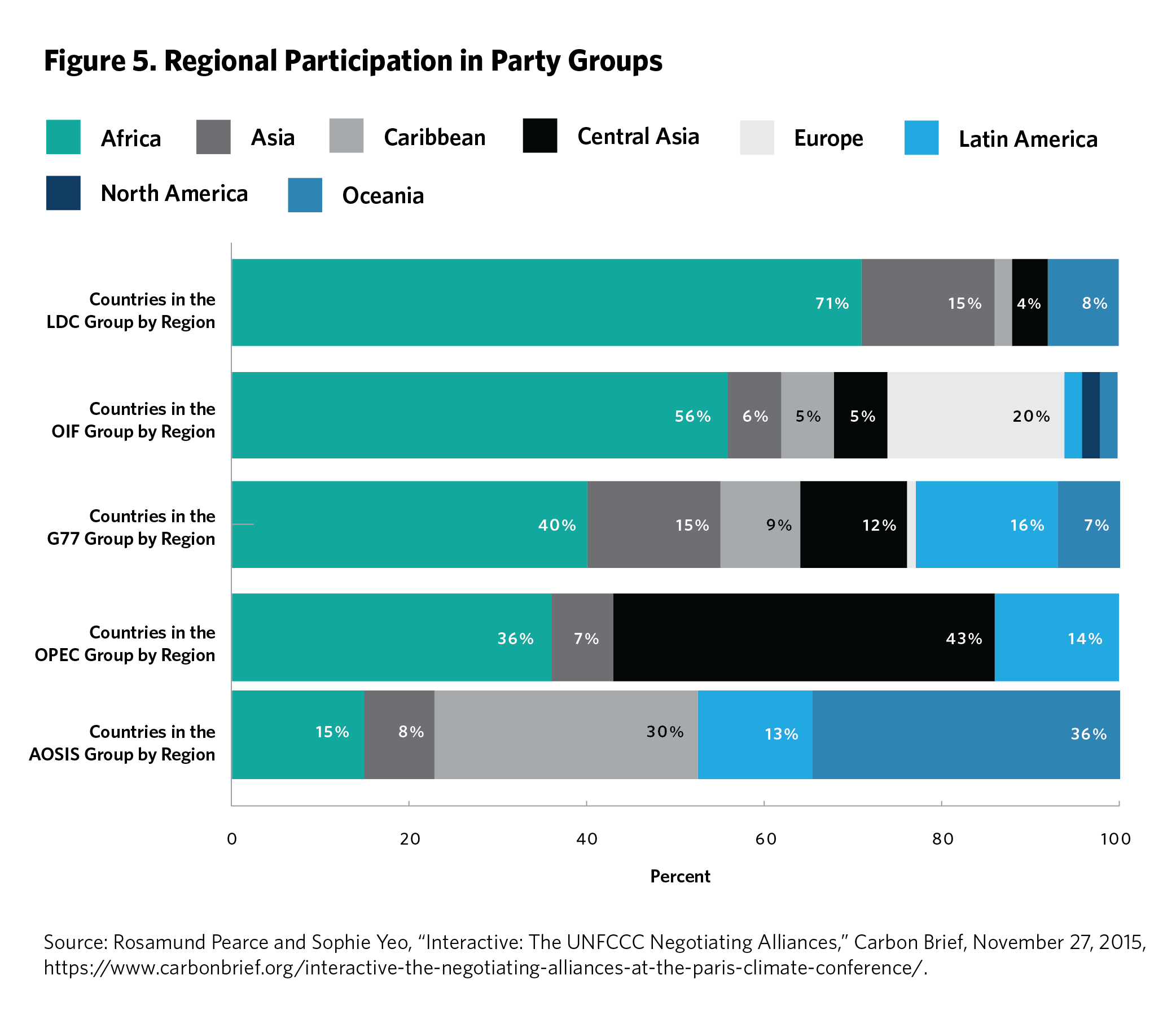

All African countries participate in at least three negotiating groups. The Africa Group, the official UN grouping for the African continent, consists of all fifty-four African countries. Besides the Africa Group, there are several other important blocs for African countries. The G77 is one of the largest and most active groups at COP—as evidenced by the success of key bloc initiatives, such as the loss and damage fund—and 40 percent of its member states are African. The Least Developed Countries (LDC) Group on Climate Change represents forty-six countries with less developed economies, 72 percent of which are African.6 South Africa, in contrast, is one of the four BASIC countries—Brazil, South Africa, India, and China—which are considered to have rapidly developing economies. Notably, the Organisation internationale francophonie (OIF) is the only UNFCCC party grouping based on a shared language and colonial history; 57 percent of its member states are from Africa. In many of these groups, Africa makes up the majority because of the sheer number of states on the continent; however, being a large region, economy, or diplomatic power does not necessarily give African countries greater influence at the climate summit.

In 1992, the Kyoto Protocol was adopted, assigning participating countries into three groups: Annex I, Annex II, and non-Annex I.7 Annex I contains OECD countries and Eastern European countries with economies in transition. Annex II contains OECD countries only; these countries were required by the Kyoto Protocol (and are now required by the 2015 Paris Agreement) to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and contribute funding for climate finance projects in developing countries. The non-Annex I category contains developing countries, including all African states, that were not subject to legal requirements under the Kyoto Protocol or the Paris Agreement.

The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) are two other influential groups at COP that African states participate in. Often, they have opposing climate priorities. AOSIS countries are some of the most vulnerable to climate change and the rising sea level, while member states of OPEC benefit from oil production—a leading cause of greenhouse gases. There are six African states in AOSIS and seven African countries in OPEC. This dichotomy reveals just one of the tensions the Africa Group must overcome to form common positions at COP.

Africa Group

The Africa Group—the continent’s formal bloc at the UN—has a three-tiered system for building consensus positions on climate change: the Committee of African Heads of State and Government on Climate Change (CAHOSCC), the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN), and the African Group of Negotiators (AGN).8There are five subgroups representing each African region (north, south, east, west, and central), which take turns selecting a chair for each tier who will each serve a two-year term. The tiers represent an alliance of the African Union (AU) member states and present the interests of the continent at the COP negotiations. This allows Africa to speak on some issues with a common and unified voice. However, it also slows the process and can lead to less agile negotiations.

CAHOSCC

The CAHOSCC, established in 2009, is a subcommittee of the AU that provides high-level political leadership on climate issues and approves common positions from the AGN. According to the AGN’s official website, “The CAHOSCC comprises of countries representing the five continental regions as well as leaders from countries which are chairing the AU, AMCEN, the AGN chair, as well as the Chairperson of the AU. The CAHOSCC meets at least once a year on the side lines of the AU Summit, in which key messages and decisions are taken for recording by the AU Summit.” 9 The chairmanship of the CAHOSCC is rotational. Information on the CAHOSCC’s specific mandate, how it is funded, and how it interacts with other AU offices and committees is not publicly available.

AMCEN

The AMCEN is a conference for the African ministers of environment, established in 1985, that occurs every two years. The ministers provide environmental guidance to the AGN related to each of their countries. The UN Environment Programme is the permanent secretariat of the AMCEN and administers the group’s trust fund, which pays for the AMCEN’s activities.

AGN

The AGN was established in 1995 as the technical arm of the Africa Group. It is made up of the previous chairs, the lead coordinators, the AGN secretary, strategic advisors, and the AGN plenary, comprising UNFCCC focal points and national delegations from each African country.10 The AGN prepares common positions that are adopted by ministers, participates in inter-sessional negotiations and all other COP meetings, and presents the Africa Group’s common position to the G77 and the UNFCCC at each COP. The UN Economic Commission for Africa also holds inter-sessional conferences every year for the AGN to prepare for COP. In addition, the AGN is supported by a think tank—the AGN Experts Support—made up of African experts who inform the negotiators on issues related to climate, gender, and agriculture. The AGN’s leadership comprises the chair and the secretariat.

The AGN selects lead negotiators according to specific negotiating themes, along with thematic and strategic coordinators. Coordination and communication are led by the rotating chair of the AGN and the secretariat. The AGN also holds plenary sessions three times a year to present common positions to the national African delegations and UNFCCC focal points from each African country. The AGN currently focuses on eleven thematic climate change issues impacting Africa, including adaptation finance, gender and climate change, and carbon pricing.11 All of these issues and Africa’s positions are included in the annual common position paper that is presented by the AGN chair at each COP.

The AGN is funded by seven groups: the AU; the African Development Bank; the African Climate Policy Centre; Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit, the United Nations Development Programme; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP); and SouthSouthNorth.12 Because only four of these are based in Africa, there is some risk that the role of foreign funders could influence the priorities of the AGN.

Civil Society

Civil society organizations—primarily African indigenous groups, youth groups, environmental NGOs, international NGOs, research institutions, and journalists and media organizations—often participate alongside the government delegations of developing countries. These organizations can provide expertise, attend meetings at COP, and help prepare responses to negotiation documents. Civil society organizations attend COP as observers (formally registered with the UNFCCC) but normally do not participate in the formal negotiations. African and international NGOs can make expert submissions to the UNFCCC secretariat in the months leading up to the summit. African and international NGOs also use various direct and indirect methods of participation at COPs. For example, groups can use insider strategies to network with governments or even join government delegations in closed-door negotiations. Groups may also act as technical and expert advisers during negotiations to supplement the expertise of some African negotiators, especially those from smaller and poorer countries.

Some civil society groups may act as consultants informally throughout the negotiations by answering questions on WhatsApp or on the sidelines of the negotiations. Other groups are added to the official delegations and receive badges that allow them in the room. Countries with smaller delegations tend to rely more heavily on civil society groups, including universities, to add capacity to their official delegation. Other groups use outsider strategies to influence the negotiations by organizing mass campaigns and protests, naming and shaming bad actors, and working with the media to expose climate injustice and gain public support for climate action. Another approach—the so-called boomerang effect described by Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink in their 1998 book Activists Beyond Borders—is to partner with other, often international, NGOs to strengthen their capacity or leverage the international community to condemn domestic inaction.13

African Indigenous Representation

Indigenous peoples in general continue to be poorly represented at UN climate summits: approximately 250–300 indigenous representatives came to Egypt for COP27, constituting less than 1 percent of the almost 50,000 attendees (of which around 12,000 are party delegates).14 African indigenous representatives are likewise largely missing from the climate summit. Their experiences and voices are largely excluded from submissions to the UNFCCC, in deliberations with many African countries before or during COP, and from the formal negotiations.

The Indigenous Peoples of Africa Co-ordinating Committee (IPACC) holds side events at COP to bring some of the voices of indigenous groups to the international community. Some African indigenous groups also campaign in their home countries to influence the climate positions of their governments. Examples of African indigenous groups include IPACC, the African Indigenous Foundation for Energy and Sustainable Development, the African Indigenous Women’s Organization Central African Network, Impact Kenya, the Jamii Asilia Centre, the Karamoja Women Cultural Group, the Mbororo Social and Cultural Development Association, Pawankafund, the Pastoralists Indigenous Non Governmental Organization’s Forum, and the Network of Indigenous and Local Communities for the Sustainable Management of Forest Ecosystems in Central Africa.

While these African indigenous groups raise issues that reflect on-the-ground realities in their respective countries, they often lack the capacity, opportunity, technical expertise, and influence to have their voices heard at COP. They particularly lack the financing needed to organize conferences to discuss African climate issues before the summits. Some governments do not take indigenous groups seriously because they view them as lacking scientific knowledge or technical expertise about climate change. Instead, African governments often look to international NGOs, journalists, and famous individuals like Greta Thunberg for advice, support, and guidance on climate issues.

Youth

The Youth Non-Governmental Organization (YOUNGO) group is the youth constituency for participation at COP. It includes children and youth (up to thirty-five years old) from around the world. Zimbabwe currently co-chairs YOUNGO, which gives African voices a chance to be heard. Within Africa, the African Youth Initiative on Climate Change represents the continent in YOUNGO by connecting young people to exchange ideas, share knowledge and experiences, and develop strategies to tackle climate change in Africa. In 2022, there were twenty local conferences of youth, spanning every region of Africa.15

Young people often complain of so-called youth-washing at COP, noting that although they are formally recognized as a constituency and celebrated for their more radical activism, they are seldom taken seriously in the negotiations.16 African youth have even less influence. Critical barriers to their participation in global climate forums include the lack of political inclusion at global and local stages of climate discussions, lack of access to training opportunities on climate issues, and lack of integration in climate change education.17 Other barriers include structural discrimination, systemic inequalities, adult-centric structures, and the cost of travel and accommodation.

Journalists

African and non-African journalists play a large role in bringing visibility to important topics at COP, including elevating the voices of Africans. Although the media brings greater attention to climate change, informing both the public and African delegations about key climate issues, some media narratives on climate change in Africa distort reality and create new problems. For example, some media narratives about climate change in Africa propagate the notion that African countries—with their rapid population growth and rising consumption—are culprits rather than victims of climate change, despite the fact that African countries disproportionately suffer from climate-induced disasters caused by the massive carbon emissions of developed countries.18

Journalists also provide updates on COP negotiation outcomes as well as coverage of demonstrations and protests. Some influential African news outlets that cover COP include Internews, Power Shift Africa, the Daily Nation, the Rwanda Post, Citizen TV, and Mont Jali News. The way issues are reported can impact the views of the public and influence the agenda at the climate summit.19 Media coverage of climate change in Africa leans toward crisis reporting, which neglects the common climate change–related experiences of African people. This focus on crises and disasters can be difficult to connect to their daily experiences, leading the public to view climate change as a preserve for activists, elites, and politicians.20

Journalists often communicate the positions of African governments at the climate summits and provide coverage of key negotiations and proceedings, although underreporting is also a key contributor to the lack of awareness about the climate crisis in Africa.21 Before COP, some African journalists receive training from organizations such as the African Network of Environmental Journalists and the Earth Journalism Network to better understand the UNFCCC processes and how to cover them. In addition, the Danida Fellowship Centre, funded by Denmark, supported journalists from several African countries to attend COP27. Although such financial support is crucial, foreign-funded fellowships like these may also influence how African journalists participate in and write about COP.

Environmental NGOs

Although they officially participate as observers, environmental NGOs have a crucial role to play at COP. They can strengthen stakeholder participation in the lead-up to the summit, providing negotiators with assistance during the framing of agenda items and helping the public to better understand the negotiations by translating technical language and scientific terms into simple language. NGOs also advocate for climate justice, holding governments and negotiators accountable and pushing for transparency during negotiations.

At COP28 in 2023, a coalition of African environmental NGOs––in conjunction with the African Development Bank––released five key priorities: adaptation, loss and damage, food systems, land use, and the protection and restoration of forests. The announcement of the loss and damage fund on the first day of COP, as well as various other announcements regarding food safety and land protections, is a testament to the success of these NGOs’ priorities. This is a salient example of how NGOs can influence more formal policy bodies to achieve tangible results, but it is not the only mechanism by which these organizations operate.22 Some organizations also play a key role in representing marginalized and disadvantaged groups. However, it is worth noting that some international environmental NGOs may push agendas that are not in sync with the priorities of African countries, which could lead to the misrepresentation and downplaying of African climate issues.

Research Organizations and Institutions

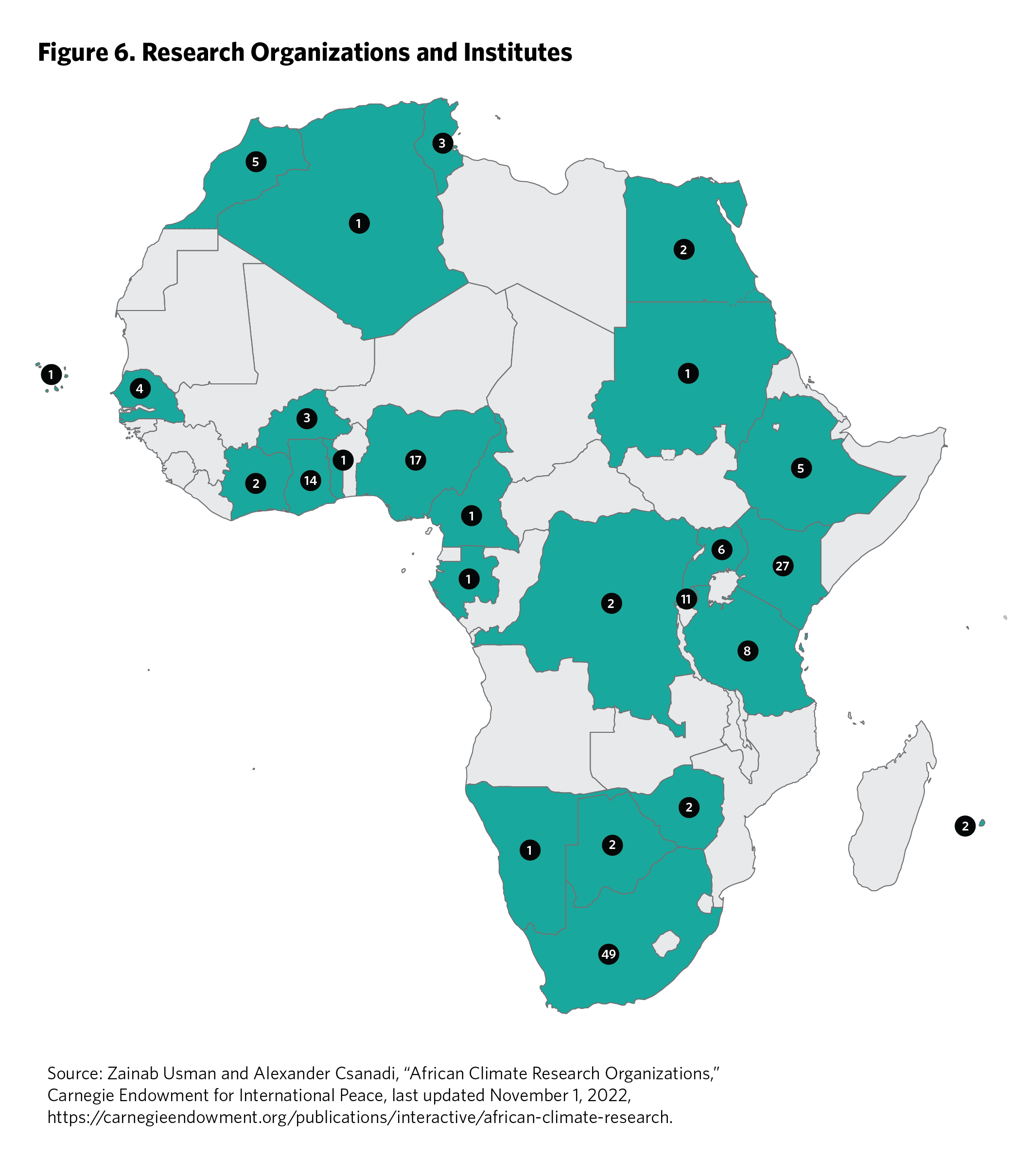

Research organizations and institutions based in Africa play a critical role in the climate negotiations (see figure 6). These organizations provide essential data and research on climate change in Africa to equip African negotiators with tangible evidence of climate change and its impact on the continent.

South Africa hosts the most research organizations (forty-nine) that work on climate issues, followed by Kenya (twenty-seven), Nigeria (seventeen), Ghana (fourteen), and Rwanda (eleven). The institutions conduct research on a variety of issues with the most common focus on forestry and agriculture, general research, and energy. For example, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, created by the South African government, conducts research into sustainable agriculture, water governance, and biodiversity. The African Centre for Biodiversity, also in South Africa, works on biosafety and seed sovereignty. The Women Environmental Programme, based in Nigeria, conducts research on gender and climate change, climate justice, green livelihoods, and clean energy.

While not all these organizations participate formally at COP, they are nonetheless important for representing African priorities at the conference. The body of rigorous analysis centered around African issues and contexts that these organizations produce is critical for policymakers and advocacy organizations to effectively champion African interests at COP.

Civil Society Alliances and Umbrella Groups

There are several umbrella groups or alliances of civil society organizations and NGOs that attend COP to speak on African issues. The Africa Climate Network includes both African and non-African scientists and researchers directly working on climate change and climate policy issues. This climate body helps in building capacity for African climate scientists. The Panafrican Climate Justice Alliance (PACJA) is a civil society network that promotes poverty reduction and equity-based climate positions useful for Africa’s negotiating strategy in global climate change politics. It helps to mobilize African climate actors toward common climate goals. At COP27, the executive director of PACJA led a protest to condemn the lack of action on loss and damage.23 This is a priority for the organization because of the need to provide reparations to communities that experience destruction of infrastructure due to extreme weather events. The African Youth Initiative on Climate Change brings together the voices of African youth to take part in international climate change conferences. It also works together with the AU and UNEP to raise awareness about environmental conservation among young people.

African civil society groups place priority on key issues including loss and damage, adaptation, and climate finance. Although there is a consensus among many African NGOs concerning these priority areas, the emphasis often depends on geographical location. What is most at stake differs from one part of Africa to another, which creates divergence of priorities. However, most groups generally agree that the primary priorities should be climate finance and adaptation issues, followed by mitigation with a special focus on reducing emissions from deforestation and the degradation of forests (REDD).24 NGOs located in East Africa and West Africa regard REDD as their top priority because they still possess vast forests that need to be safeguarded and sustainably harvested. Different priorities mean that African civil society approaches the UNFCCC processes with diverging views on how best to deal with climate change issues.

Interests and Influence: Key Factors and Determinants

There are several competing factors that help determine climate priorities—or differences—among African countries, including geography, economy, language, and negotiating capacity. Because of these continent-wide divergences, regional groups within Africa are more effective at determining common interests and negotiating strategies before negotiators develop consensus positions as the Africa Group.

Geography

Africa has six island states, thirty-two coastal states on the mainland, and sixteen landlocked states. The geographic difference between these small island states and continental Africa has a major impact on the countries’ climate priorities. Even within continental Africa, priorities diverge—for example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with 25 miles of coastline, has very different resources and priorities from South Africa, whose coast is 1,704 miles.

These geographic differences mean that African countries often represent their priorities through regional groups such as AOSIS and the Coalition for Rainforest Nations (CFRN), which includes twenty-two African members. Since all African states are members of multiple negotiating groups, it is difficult to juggle differing priorities. For example, according to Carbon Brief, the Africa Group’s top priority at COP27 was the global stocktake, while the highest priority for AOSIS was loss and damage.25

The continent of Africa also contains nine out of the fourteen types of biomes, including desert, savannah, and subtropical and tropical rainforest.26 However, there is no evidence that the biomes themselves cause a country’s priorities to differ from Africa’s overarching priorities of adaptation, climate finance, and sustainable development.

Economic Size

The size and type of national economies is the most important driver of different climate priorities between African countries. For example, the seven African countries that are part of OPEC have incentive to prioritize prolonging the global use of fossil fuels because their economies depend on oil exports. The thirty-four African LDCs, on the other hand, demand funding for loss and damage and climate adaptation. Here, too, states rely on regional groupings to form climate positions based on their economic priorities—five African countries are part of the Arab Maghreb Union, fifteen are part of the Economic Community of West African States, and twenty-one are part of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa.

While economic differences may cause rifts in the climate priorities of the Africa Group, there are also mutual benefits to having both large and small economies within the continent. Small economies can rely on the greater diplomatic capacity of more developed countries. In turn, larger economies in Africa get to negotiate alongside smaller economies who have moral high ground because they are low emitters of greenhouse gases.

Language

Language is frequently identified as a barrier to participation at COP. The UNFCCC conference is held largely in English with simultaneous translation. Delegates from non-English-speaking countries sometimes struggle with this aspect of negotiations. For many negotiators, the ability to speak English represents a huge advantage. Within Africa, languages vary by region and often reflect the legacy of colonialism. At COP, not only do countries meet with their negotiating groups (for instance, the G77, the AGN, or AOSIS), but they also have group meetings based on language. For Africa, the most common language-based groups are French and Portuguese. Representation from the African continent includes twenty-eight French-speaking countries (that are all part of the OIF), one Spanish-speaking country, six that speak Portuguese, and twenty-four countries that use English as one of their main languages. The language-based meetings help delegates from non-English-speaking countries share information and strategize on their positions.

Capacity and Preparedness

As shown in figure 2, many African countries have only recently begun sending significant delegations to the climate negotiations and investing in their participation. Countries that have just started to participate also struggle to make the alliances and relationships necessary to successfully broker deals. There are several programs aimed at building Africa’s capacity to participate fully in the negotiations, including the European Capacity Building Initiative, Legal Response International, the Cluster Lusophone (for Portuguese-speaking countries), and the Africa Climate Policy Centre. However, many of these programs are funded by the United States or European countries and some negotiators have been critical of the content and ideologies embedded in the curriculum.27 Thus, there could be a trade-off between retaining full autonomy over negotiation strategy and prioritization, and maintaining access to resources to improve negotiators’ efficacy at these forums.

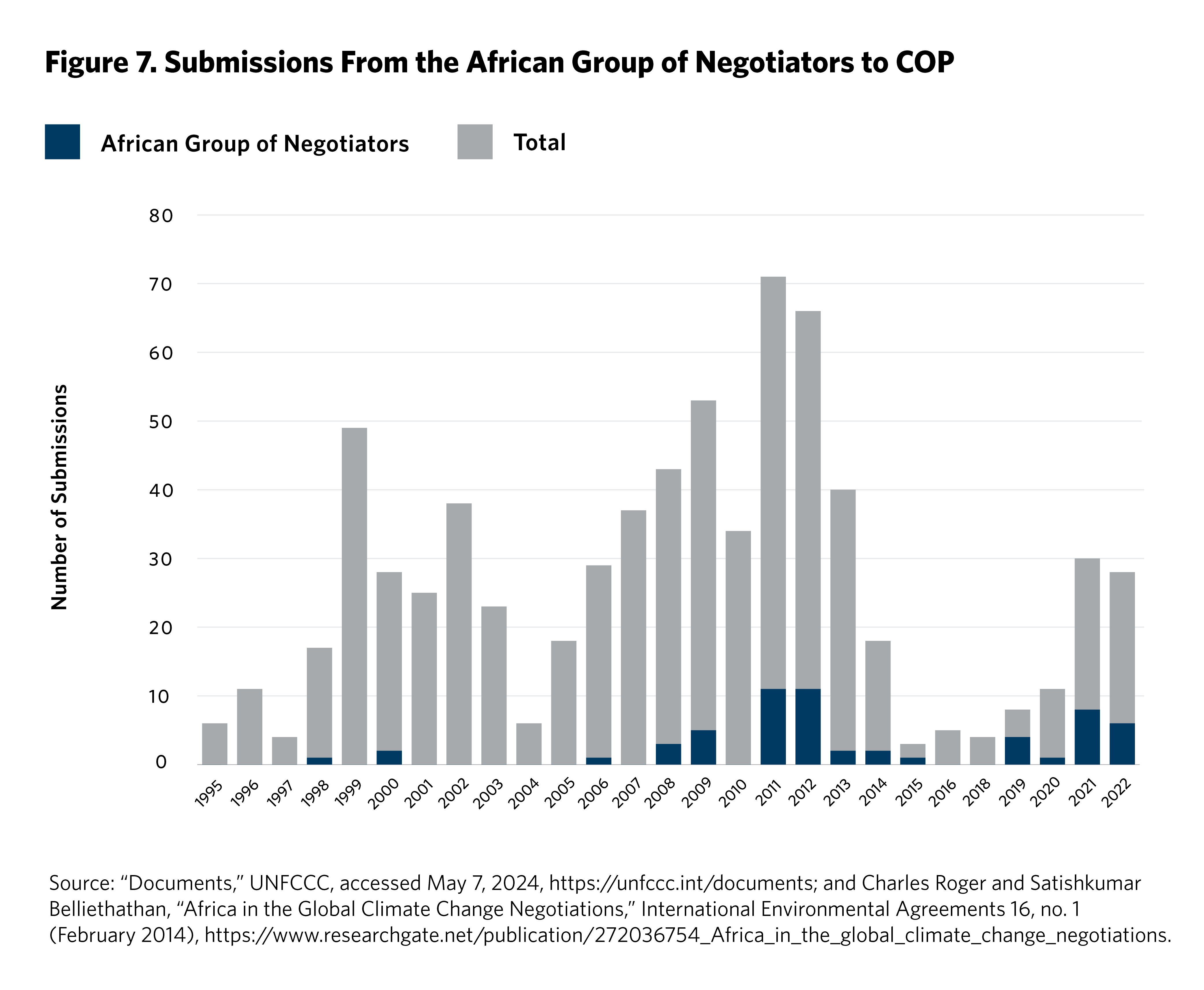

Regardless of the challenges, there is much reason for optimism as the capacity of African countries to participate in the climate negotiations has increased since the first COP in 1995.28 As shown in figure 7, AGN has increased, perhaps irradicably, the number of submissions and statements they present to inform the UNFCCC working groups. Additionally, all African countries have submitted nationally determined contributions (NDCs),29 and many have submitted national adaptation programs (NAPs).30 NDCs are the greenhouse gas emissions reductions that countries commit to achieving over a given period, accompanied by a tangible roadmap for achieving these targets. Per the 2015 Paris Agreement, each country is required to submit its NDC so that the UNFCCC can calculate whether the world will hit its global emission reductions goals. UNEP assists every country to develop NAPs, which address climate vulnerabilities specific to each country and integrate policy-driven solutions into government plans. The development of NDCs and NAPs shows that many African countries have improved their national capacity and planning for climate change.

Recent participation in regional conferences also signals an increased commitment by African countries to gain institutional knowledge and build consensus on climate matters. Africa has hosted COP five times (Morocco in 2001 and 2016, Kenya in 2006, South Africa in 2011, and Egypt in 2022), which has allowed the host country on each occasion—the symbolic leader of the event—to set the agenda for the climate negotiations and emphasize African priorities.31 COP27, held in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, at the end of 2022, was commonly referred to as the “Africa COP.” One of the significant outcomes of COP27 was the creation of a loss and damage fund—a major win for Africa, particularly for the most vulnerable countries and the small island states.

Still, some African delegations and civil society members expressed disappointment after COP27 and COP28 that more was not done to further the implementation of NDCs in developed countries or to increase climate finance contributions. While progress has certainly been made, there is clearly much left to be understood regarding the nature of African negotiating capacity and the channels by which it has been and will continue to be augmented.

Conclusion

Since 1995, Africa has increased its voice and presence dramatically at COP. African representation at COP takes many forms. The formal, three-tiered Africa Group has become a leader in the fight against climate change given Africa’s vulnerability, large population, and abundant natural resources. Other negotiating groups offer African countries the ability to advocate for priorities that may not be shared across the continent. And African civil society actors, who are active in shaping the climate agenda at the national and international level, use both insider and outsider strategies to influence the negotiations.

Despite these benefits, the broader developing world is still unable to exercise its leverage to shape outcomes at COP. Global North countries continue to underfund adaptation and loss and damage in the Global South and postpone their own commitments to reduce emissions.32 Just weeks before COP28, inter-sessional discussions had reached a dead end as rich and poor countries clashed over how to finance the loss and damage fund. Developing countries had been explicit about the dire need for climate financing from the Global North, but had so far been unable to convince them to pay. The announcement of the loss and damage fund on the first day of the conference was encouraging––and the $700 million in contributions thus far is a good start––but ultimately the scale of this funding pales in comparison to the annual global economic costs arising from climate change.33

Despite the apparent improvement in African actors’ ability to influence global climate debates, clearly there is room for more growth. A more nuanced understanding of what negotiating capacity means for African countries and the ways in which that capacity may be improved upon are promising areas for future research. One particularly critical channel is investigating how to coordinate and aggregate the power of negotiating in large blocs while simultaneously balancing the often divergent priorities of African countries.

Who speaks for Africa at COP is a complicated fabric of formal and informal institutions, some of which receive significant support from non-African actors. Promisingly, these disparate voices have become better organized over time. But the power dynamics of the global climate regime remain broadly unresponsive and these African voices are largely left waiting for change.

Notes

1 “CDP Africa Report,” CDP, March 2020, https://www.cdp.net/en/research/global-reports/africa-report.

2 Florent Baarsch and Michiel Schaeffer, “Climate Change Impacts on Africa's Economic Growth,” African Development Bank, 2019, https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/afdb-economics_of_climate_change_in_africa.pdf.

3 Courtney Lindwall, “What Is Greenwashing?” Natural Resources Defense Council, February 9, 2023, https://www.nrdc.org/stories/what-greenwashing?gclid=Cj0KCQjwrMKmBhCJARIsAHuEAPSTY4ZptiJfAbkKO2z9zOiYhwQgskKKTaEdYqKUmRYuf_J_87nG5v8aAvPxEALw_wcB.

4 “G-77 Home,” Group of 77 at the United Nations, January 2024, https://www.g77.org/.

5 Rosamund Pearce and Sophie Yeo, “The UNFCCC Negotiating Alliances,” Carbon Brief, December 3, 2018, https://www.carbonbrief.org/interactive-the-negotiating-alliances-at-the-paris-climate-conference/.

6“Home,” LDC Climate Change, accessed April 18, 2024, https://www.ldc-climate.org/.

7“Parties & Observers,” UNFCCC, accessed April 18, 2024, https://unfccc.int/parties-observers.

8“About the AGN,” African Group of Negotiators, February 8, 2022, archived March 1, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, https://web.archive.org/web/20240301120838/https://africangroupofnegotiators.org/about-the-agn/.

9African Group of Negotiators, “About the AGN.”

10 African Group of Negotiators, “About the AGN.”

11 “African Group of Negotiators Consolidate Common Draft Position in Lead Up to COP27,” UNECA, August 3, 2022, https://www.uneca.org/stories/african-group-of-negotiators-consolidate-common-draft-position-in-lead-up-to-cop-27.

12 “Partners and Key Stakeholders,” African Group of Negotiators, July 11, 2018, archived March 1, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, https://web.archive.org/web/20240302131358/https://africangroupofnegotiators.org/about-the-agn/partners-and-key-stakeholders/.

13 Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998).

14 Ayurella Horn-Muller, “Indigenous Activists ‘Seen, not Heard’ at COP27,” Axios, November 18, 2022. https://www.axios.com/2022/11/18/indigenous-activists-seen-not-heard-at-cop27.

15“LCOY 2022,” United Nations YOUNGO, accessed April 18, 2024, https://www.lcoy.earth/

16Eduarda Zoghbi, “Beyond ‘Youthwashing’: How to Make Youth Representation at COP Meetings More Impactful,” State of the Planet, November 16, 2021, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/11/16/beyond-youthwashing-how-to-make-youth-representation-at-cop-meetings-more-impactful/.

17“African Youth and Climate Change: A Policy Brief in Light of COP-27” The Youth Café, October 2022. https://www.theyouthcafe.com/policy-briefs/african-youth-and-climate-change-a-policy-brief-in-light-of-cop-27.

18“Africa Suffers Disproportionately From Climate Change,” World Meteorological

Organization, September 4, 2023, https://wmo.int/media/news/africa-suffers-disproportionately-from-climate-change.

19“Climate change in Africa: Is Africa sleepwalking to disaster?” Africa No Filter, March 2022. https://africanofilter.org/climate-change-in-africa-is-africa-sleepwalking-to-disaster.

20Enock Sithole, “Climate Change Journalism in South Africa Misses the Mark Ignoring the People’s Daily Experiences,” Conversation, June 19, 2023, https://theconversation.com/climate-change-journalism-in-south-africa-misses-the-mark-by-ignoring-peoples-daily-experiences-207229.

21World Meteorological Organization, “Africa Suffers Disproportionately From Climate Change.”

22“COP28: African Civil Society Unveils Its Recommendations for the Fight Against Climate Change in Africa,” African Development Bank, December 6, 2023. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/cop28-african-civil-society-unveils-its-recommendations-fight-against-climate-change-africa-66720.

23 Godwin Oritse, “COP 27: PACJA Protest Non-negotiation of Loss, and Damage for Africa Nations,” Vanguard, November 15, 2022, https://www.vanguardngr.com/2022/11/cop-27-pacja-protest-non-negotiation-of-loss-damage-for-africa-nations/.

24 Farayi Madziwa and Carola Betzold, “20 Years of African CSO Involvement in Climate Change Negotiations: Priorities, Strategies and Actions,” Heinrich Böll Stiftung Southern Africa, 2014, https://ng.boell.org/sites/default/files/cso_handbook_final_english_1.pdf.

25Aruna Chandrasekhar et al., “Interactive: Who Wants What at the COP27 Climate Change Summit,” COP27 Carbon Brief, February 11, 2022, https://www.carbonbrief.org/interactive-who-wants-what-at-the-cop27-climate-change-summit/.

26Anthony R.E. Sinclair and Rene L. Beyers, “African Biomes,” Ecology (September 29, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199830060-0112.

27Informal conversations with participants and negotiators by authors at COP27 and COP28.

28 Charles Roger and Satishkumar Belliethathan, “Africa in the Global Climate Change Negotiations,” International Environmental Agreements 16 (2016), https://econpapers.repec.org/article/sprieaple/v_3a16_3ay_3a2016_3ai_3a1_3ap_3a91-108.htm.

29“Nationally Determined Contributions,” UNFCCC, accessed April 18, 2024, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs.

30“National Adaptation Plans,” UN Environment Programme, accessed April 18, 2024, https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/climate-action/what-we-do/climate-adaptation/national-adaptation-plans.

31Roger and Belliethathan, “Africa in the Global Climate Change Negotiations.”

32Thalif Deen, “COP27: A Climate Summit Following Empty Promises & Funding Failures,” Global Issues, November 4, 2022, https://www.globalissues.org/news/2022/11/04/32326; and “Global Talks on Climate ‘Loss and Damage’ Fund End in Failure Ahead of COP28,” Carbon Brief, October 23, 2023. https://www.carbonbrief.org/daily-brief/global-talks-on-climate-loss-and-damage-fund-end-in-failure-ahead-of-cop28.

33Martina Igini, “Loss and Damage Fund Contributions at COP28 So Far Cover Less Than 0.2% Of Climate-Related Losses in Developing Countries,” Earth.org, December 8, 2023, https://earth.org/loss-and-damage-fund-contributions-at-cop28-so-far-cover-less-than-0-2-of-climate-related-losses-in-developing-countries.