Commercial hacking tools have become increasingly accessible to both state and nonstate actors. As a result, governments are struggling to balance the legitimate uses of some of these tools against the dangerous risks they may pose to democracy, rule of law, and civilian safety. Both authoritarian regimes and democratic governments are known to use intrusive cyber capabilities against their own citizens, including to surveil and suppress journalists, activists, and political dissidents. These tools also pose dangers in the hands of financially or politically motivated nonstate actors who operate under limited government oversight or regulatory constraint.

But hacking tools are not only used by bad actors for malintent. Legitimate security researchers (often called “white-hat” hackers) often use these same tools to detect vulnerabilities and security risks in technological systems, and governments need some degree of access to hacking tools for national security interests.1 Thus, the idea of an outright ban on commercial hacking tools—while appealing at face value—is ultimately untenable.

Two major government initiatives seek to limit the proliferation of commercial hacking tools: one is by the United States, outlined in the U.S. Joint Statement on Efforts to Counter the Proliferation and Misuse of Commercial Spyware, and another is by the United Kingdom and France, introduced in the Pall Mall Process (PMP). The two efforts share the same goal, a safer cyber landscape, but have pursued separate courses of action to achieve it. The United States has focused much of its policy maneuvering on achieving specific government action that will limit the use, sale, and procurement of commercial spyware. To do this, Washington has used economic sanctions, export controls, and visa restrictions. By contrast, the UK and France have chosen to address the broad suite of commercial hacking tools and establish principles and policy options for states, industry, and civil society. Adapting existing international norms frameworks, such as the UN framework on responsible state behavior in cyberspace and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the UK and France seek to create an “inclusive global process.”2

These initiatives are a step in the right direction, but the incongruity in methodology and design is concerning. Governments lacking advanced technological capabilities of their own will cling to the ability to purchase and deploy offensive cyber capabilities at will. Countries that have a spotty history with spyware—such as Greece,3 Italy,4 and Singapore5—should not be able to participate in norms-building engagements through the PMP while continuing to use commercial spyware to spy on their citizens. Nor should Cyprus (a signatory of the PMP) be able to turn a blind eye as questionable surveillance companies take advantage of the country’s lax regulatory environment to set up shop.6 And while spyware tools may get the most media attention, governments contribute to the broader cyber intrusion industry by paying millions of dollars to private companies for a variety of covert offensive cyber capabilities.7 Without a harmonized, cohesive strategy, governments will continue to spy on their citizens and contribute to the growing industry of hackers and cyber criminals.

This article aims to outline efforts by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France to tame the commercial hacking marketplace while demonstrating the need for a unified, cohesive governmental strategy that will create real improvements in digital safety. While there is certainly a role for civil society and industry actors to shape the implementation of such a strategy, this piece primarily focuses on state behavior and government-led initiatives.

The Hacking Marketplace

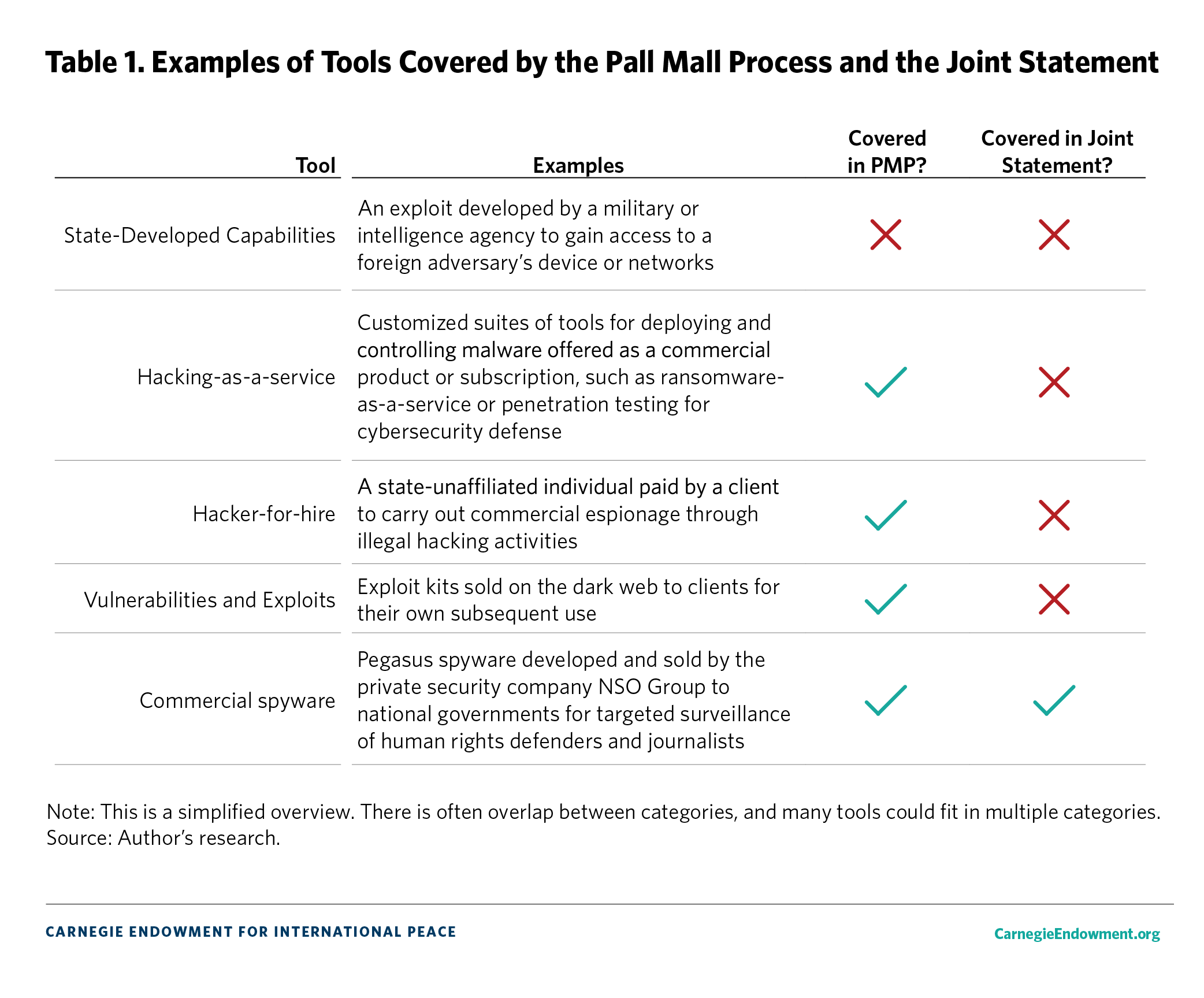

The cyber tools discussed in the U.S. Joint Statement and in the PMP are different in use and nature. The PMP covers a larger segment of commercially available cyber tools (see table 1) but does not explicitly describe offensive capabilities developed for use by state-backed intelligence agencies. The U.S. campaign exclusively targets commercial spyware tools.

As the marketplace of commercial hacking tools grows in both size and sophistication, offensive cyber capabilities are becoming more accessible to a wider range of governments, organizations, and individuals. In 2023, the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) warned that the proliferation of commercially available illicit cyber tools and services will lower the barriers of entry for state and nonstate actors to acquire capabilities equal to those of advanced persistent threat groups.9 These tools are often developed by access-as-a-service (AaaS) firms—companies and individuals operating overtly or on the so-called dark web—who seek out and identify vulnerabilities in software and hardware that might lend customers an initial foothold into victims’ systems.10 Cyber tools sold on the AaaS market include tailored hack-for-hire intrusion services, off-the-shelf hacking-as-a service products, and vulnerability capabilities like zero-click exploits.11 Such tools are used by nonstate actors to conduct low-grade cyber crime, by criminal groups to steal information, and by states for complex cyber espionage campaigns.

One particularly pernicious capability available on the AaaS marketplace is commercial spyware: malware developed and sold by private companies to monitor and extract sensitive data from devices without the knowledge or consent of users. A recent study from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace found that at least seventy-four countries have purchased and used commercial spyware.12 Spyware tools developed by Israel-based NSO Group and Ireland-based Intellexa, both targets of punitive restrictions by the United States, have been used to surveil journalists and opposition politicians around the world. Commercial spyware has also been deployed against U.S. government personnel: in 2023, just as President Joe Biden’s administration announced its Executive Order (EO) on Spyware, the White House announced that at least fifty U.S. officials had been targeted by commercial spyware, with additional instances reported since.13

Governments contribute to the commercial hacking marketplace in several ways. State cyber capabilities developed in-house by intelligence agencies can be leaked to foreign governments and companies.14 For example, an exploit originally engineered by the United States was later repurposed and used by North Korea and Russia, respectively, in the 2017 WannaCry and NotPetya ransomware attacks.15 Governments also train future so-called cyber mercenaries who can take their technological expertise and state secrets to the highest bidder once they leave the government. In 2021, three former U.S. intelligence officers admitted that they were hired by the United Arab Emirates for their cyber expertise after prosecutors found that they “expanded the breadth and increased the sophistication” of the Emirati government’s offensive cyber operations.16 Finally, governments participate in the commercial hacking marketplace as significant buyers. Government agencies will often purchase offensive cyber capabilities from private security companies and individuals on the gray market for law enforcement and national security uses.17 The infamous spyware vendor NSO Group counts governments around the world as its primary customers, claiming “NSO products are used exclusively by government intelligence and law enforcement agencies to fight crime and terror.”18 The potential use of NSO Group’s technology to spy on political dissidents and human rights activists has been at the center of spyware scandals involving countries such as Poland, Saudi Arabia, and Spain.19

The hacking marketplace appears to be growing rapidly. So-called zero-day exploits—or previously unknown, currently exploitable security vulnerabilities that are exploited in a given system—increased by 50 percent in 2023 according to research from Google.20 The use of these zero-day exploits was attributed to espionage actors, ransomware gangs, and financially motivated hackers. The rapid pace of proliferation necessitates cohesive government action to regulate and constrain the market through which cyber intrusion capabilities are bought and sold. Without a coordinated government response, the hacking marketplace will continue to supply the capabilities used in devastating attacks like the recent Change Healthcare and Medibank hacks.21

The U.S. Approach: Specific Action Aimed at Spyware

The United States continues to direct its efforts toward constraining the commercial spyware industry through government action. The U.S. EO restricts the U.S. government’s operational use and procurement of spyware tools that pose risks to national security, rule of law, and human rights. The EO includes key provisions for reporting requirements, risk assessment, and the promotion of responsible use. The U.S.-led Joint Statement, the first international commitment for collective action on the proliferation of commercial spyware, aims to build a coalition of states who can emulate the EO and implement their own domestic guardrails against spyware. The hope is that the cumulative effect of such restrictions will effectively close off a significant piece of the spyware market currently available to bad actors.

On March 5, 2024, the United States announced sanctions against two individuals and five entities associated with the proliferation of spyware: Tal Jonathan Dilian, the founder of the spyware vendor Intellexa; Sara Aleksandra Fayssal Hamou, an affiliate of Intellexa; Greece-based Intellexa S.A.; Ireland-based Intellexa Limited; North Macedonia–based Cytrox AD; Hungary-based Cytrox Holdings ZRT; and Ireland-based Thalestris Limited.22 The U.S. State Department and Commerce Department have also implemented visa restrictions and export controls on individuals and firms connected to the development and dissemination of spyware.23

At the third Summit for Democracy hosted by South Korea, the United States added six more countries to the original eleven signatories of the Joint Statement.24 Ireland, where Intellexa established operations, and Poland, whose previous Law and Justice party government was recently reported to have targeted almost 600 people with Pegasus spyware, were both added.25 South Korea and Japan also joined the coalition, expanding the initiative beyond European partners. Even with these additions, the coalition the United States has built around the Joint Statement remains a small group of countries with a relatively narrow focus on countering commercial spyware.

The UK-France Approach: Creating a Normative Framework

The approach pursued by the UK and France speaks to a broader set of cyber tools and focuses on big-tent diplomatic achievements. The recently published Pall Mall Declaration refers to the multitude of cyber intrusion capabilities available in the current commercial marketplace, including spyware, hackers-for-hire, and vulnerability exploits. The new initiative recognizes the legitimate uses for some of these cyber tools (such as those needed for red-teaming and penetration testing by security researchers); instead of “naming and shaming” actors who have a track record of abuse, it endeavors to integrate international law, human rights law, and existing norms into a framework for the responsible use of cyber intrusion capabilities.26 The PMP highlights four activities to guide the formation of voluntary norms in this area: holding states accountable when behavior is inconsistent with international human rights law, developing precise conditions for use, implementing assessment and due diligence mechanisms for users and vendors, and conducting business transactions with transparency.

A focal point of the PMP is the inclusion of a broader set of government stakeholders beyond what experts involved in the PMP call “like-minded” states.27 With the overarching goal of working with this larger group to clarify what legitimate use looks like in the context of intrusive surveillance capabilities, the PMP brings in participation from nongovernmental entities as well, including civil society organizations, security researchers, academia, and private industry. This whole-of-society approach strengthens the ability of these actors to support victims in incident response, conduct in-depth reporting and investigations, and highlight policy options for governments.28

Weighing the Two Strategies

| Table 2: Government Action Taken on Commercial Spyware in the United States, France, and the UK | ||||

| Domestic Guardrails | Export Restrictions | Economic Sanctions | International Diplomatic Efforts | |

| United States | Mature29 | Mature30 | Developing31 | Mature32 |

| France | Underdeveloped | Underdeveloped | Underdeveloped | Mature33 |

| United Kingdom | Underdeveloped | Underdeveloped | Underdeveloped | Mature34 |

|

Mature = Three or more cases of actions in category Developing = One or two cases of action in category Underdeveloped = no recorded cases of action |

||||

The U.S. focus on commercial spyware has clear benefits in the short term. The commercial spyware industry is widely associated with both human rights abuses and counterintelligence threats, rendering it an easily explainable policy concern for leaders seeking to create positive change in cyberspace. By focusing diplomatic and domestic resources on a smaller issue set and tighter group of stakeholders, the United States has achieved a series of diplomatic and domestic policy achievements in a short period of time (see table 2). The prioritization of concrete action on spyware constrains the behavior of malicious actors and those most prominently profiting from such abuses while simultaneously signaling that the United States is not a viable marketplace for them.

To seize the strong degree of political will toward addressing specific spyware concerns following the EO and Joint Statement, the U.S. effort largely excludes the wider marketplace of surveillance and intrusion capabilities, such as exploit kits sold on the dark web. Thus, while countries may agree to regulate the use of commercial spyware tools, they could still retain the flexibility to purchase other exploits from the vulnerability market themselves—for military, intelligence, or law-enforcement purposes. Unbridled use of these capabilities by governments can be dangerous for national security and civilian well-being, as well. The Russian government is known to turn to private companies for exploits used in state-run offensive cyber operations, illustrating the need for Western governments to focus on the wider hacking marketplace as an area of national security concern.35

Acknowledging the progress the United States has already made on commercial spyware, the UK and France have focused on driving diplomatic cooperation in the broader cyber intrusion marketplace. The UK and France utilize the term “commercially available cyber intrusion capabilities” to refer to the multitude of these products available in the current ecosystem, including spyware, initial access brokers (so-called hacking-for-hire), and vulnerability exploits.36 The PMP includes a broad set of governments, the private sector, and civil society as signatories to the initiative, creating an expansive forum for different partners to interact and engage on these issues.

With a focus on developing shared definitions and conditions for legitimate use, the UK and France built on previous coalition-building initiatives such as the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace,37 the industry-led Tech Accord,38 and the UN’s framework for responsible behavior in cyberspace.39 Many of the terms used in cyber-norms frameworks—such as “cyber intrusion capabilities”—are ill-defined, allowing governments and other cyber actors to use the ambiguity around surveillance tools to abuse the technology. Precision of language, a primary goal of the PMP, is necessary to achieve proper oversight and accountability over the long term and is largely missing from current frameworks.

However, despite language in the PMP encouraging the development of national restrictions and accountability frameworks, neither France nor the UK have passed their own restrictions against the commercial hacking industry. The EU’s strict regulations around the sale of spyware have not prevented spyware vendors from frequently taking advantage of states who ignore violations or refuse to enforce regulations.40 As a result, Europe has become a breeding ground for the development and sale of commercial spyware.41 Absent more concrete action, the UK-France initiative risks advancing a largely symbolic strategy bolstering long-term norms without much real-world progress.

A Way Forward

The current efforts by the United States, France, and the UK are great starting points for a comprehensive, global strategy that addresses the dynamic nature of cyber threats. Still, the Joint Statement and PMP are encountering a common problem seen in past efforts to regulate cyberspace: an absence of harmonized action and responses.42

Efforts to counter the proliferation of commercial hacking tools should prevent government actors from metaphorically checking the box by signing onto joint initiatives while ignoring calls for concrete action. This could especially be the case with countries that have a track record of using these capabilities to impede human rights. Likewise, many states lack the technical expertise and resources necessary to develop their own offensive cyber capabilities and rely on the commercial hacking marketplace to keep pace with national adversaries. These are the state actors who will take advantage of gaps in disjointed regulatory frameworks.

The United States, the UK, and France are already working closely together on this issue, but action is needed to ensure individual efforts work in harmony. Cohesion among the leading government players, in addition to support from industry and civil society, will help fill gaps seen in current frameworks. Possible steps forward could include the following, laid out in table 3.

| Table 3. Recommendations to Further Cohesion in the Regulation of Hacking Tools | |

| Recommendations | Implementing Stakeholders |

| Develop concrete actions that can be tailored to specific legal and regulatory contexts outside of the United States | National governments Civil society organizations< Private sector companies |

| Create a shared timeline for the execution of these actions | National governments Civil society organizations |

| Provide shared expectations, standards, and requirements to participating countries while staying consistent with enforcement | National governments |

| Establish an expectation that governments sign both the Joint Statement and Pall Mall Process; signing one can be an informal on-ramp to the other | National governments< Civil society |

Conclusion

The United States and its allies in the UK and France may be following different theories of change, but their approaches can be complementary when both parties present a united front, fusing both regulatory action and multistakeholder engagement. To successfully curb the robust industry of commercial hacking tools, coalition- and norms-building efforts should be paired with concrete action in a harmonized approach. The recent spyware sanctions are an important move by the United States, and its EO, export controls, and visa restrictions have built significant momentum for targeting the commercial spyware industry. But the United States cannot keep the momentum going without meaningful buy-in from its allies, and the larger swath of cyber intrusive capabilities requires an equal level of prioritization and governance. The PMP and further efforts from the UK and France have the potential to complement existing efforts by the United States and create durable policy changes that contribute to a safer, more responsible cyber ecosystem. The creation of one cohesive approach that combines the strength of the efforts by the United States, the UK, and France would allow for better accountability, clearer criteria for best practices, and increased pressure on misbehaving actors.

Going forward, international stakeholders need to ask: How can the success of different government approaches be measured? What does success look like? What is the role of private technology companies? And as actors find new ways to apply artificial intelligence to cyber operations, how will AI change the landscape of the commercial hacking industry? Careful consideration of these questions will aid governments in designing the most optimal framework to reign in the commercial hacking industry.

Notes

1 Gavin Wilde and Emma Landi, “Exploring Law Enforcement Hacking as a Tool Against Transnational Cyber Crime,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 23, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/04/exploring-law-enforcement-hacking-as-a-tool-against-transnational-cyber-crime?lang=en.

2 “The Pall Mall Process Declaration: Tackling the Proliferation and Irresponsible Use of Commercial Cyber Intrusion Capabilities,” UK Government, February 6, 2024, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-pall-mall-process-declaration-tackling-the-proliferation-and-irresponsible-use-of-commercial-cyber-intrusion-capabilities.

3 Nektaria Stamouli, “Greece’s Spyware Scandal Expands Further,” POLITICO, November 5, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/greece-spyware-scandal-cybersecurity.

4 Zeba Siddiqui, “Apple and Android Phones Hacked by Italian Spyware, Google Says,” Reuters, June 23, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/technology/apple-android-phones-hacked-by-italian-spyware-google-says-2022-06-23.

5 David Sun, “Singapore Cyber-Security Firm Blacklisted by the US Along With Those Linked to Pegasus Spyware,” The Straits Times, November 4, 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singapore-cyber-security-firm-blacklisted-by-the-us-along-with-those-linked-to-pegasus.

6 David Kenner and Eve Sampson, “Spyware Firm Intellexa Hit With US Sanctions After Cyprus Confidential Exposé,” ICIJ, March 6, 2024, https://www.icij.org/investigations/cyprus-confidential/spyware-firm-intellexa-hit-with-us-sanctions-after-cyprus-confidential-expose.

7 Sven Herpig and Alexandra Paulus, “The Pall Mall Process on Cyber Intrusion Capabilities,” Lawfare, March 19, 2024, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/the-pall-mall-process-on-cyber-intrusion-capabilities.

8 Steven Feldstein and Brian (Chun Hey) Kot, “Why Does the Global Spyware Industry Continue to Thrive? Trends, Explanations, and Responses,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 14, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/03/14/why-does-global-spyware-industry-continue-to-thrive-trends-explanations-and-responses-pub-89229.

9 National Cyber Security Centre, “The Threat From Commercial Cyber Proliferation,” April 19, 2023, https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/report/commercial-cyber-proliferation-assessment.

10 Winona DeSombre et al, “Countering Cyber Proliferation: Zeroing in on Access-as-a-Service,” Atlantic Council, March 1, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/countering-cyber-proliferation-zeroing-in-on-access-as-a-service.

11 DeSombre et al, “Countering Cyber Proliferation.”

12 Feldstein and Kot, “Why Does the Global Spyware Industry Continue to Thrive?”

13 Sean Lyngaas, “White House Says 50 US Officials Targeted With Spyware as It Rolls Out New Ban of Hacking Tools,” CNN, March 27, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/27/politics/us-government-bans-spyware/index.html.

14 DeSombre et al, “Countering Cyber Proliferation.”

15 Gil Baram, “The Theft and Reuse of Advanced Offensive Cyber Weapons Pose a Growing Threat,” Council on Foreign Relations, June 19, 2018, https://www.cfr.org/blog/theft-and-reuse-advanced-offensive-cyber-weapons-pose-growing-threat.

16 Mark Mazzetti and Adam Goldman, “Ex-U.S. Intelligence Officers Admit to Hacking Crimes in Work for Emiratis,” New York Times, September 14, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/14/us/politics/darkmatter-uae-hacks.html.

17 Lillian Ablon, Martin C. Libicki, and Andrea M. Abler, “Markets for Cybercrime Tools and Stolen Data: Hackers' Bazaar,” RAND Corporation, 2014, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR610.html.

18 “About Us,” NSO Group, https://www.nsogroup.com/about-us.

19 Shaun Walker, “Poland Launches Inquiry Into Previous Government’s Spyware Use,” The Guardian, April 1, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/apr/01/poland-launches-inquiry-into-previous-governments-spyware-use; Stephanie Kirchgaessner, “Saudis Behind NSO Spyware Attack on Jamal Khashoggi’s Family, Leak Suggests,” The Guardian, July 18, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/18/nso-spyware-used-to-target-family-of-jamal-khashoggi-leaked-data-shows-saudis-pegasus; Dana Priest, “A UAE Agency Put Pegasus Spyware on Phone of Jamal Khashoggi’s Wife Months Before His Murder, New Forensics Show,” Washington Post, December 21, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/interactive/2021/hanan-elatr-phone-pegasus; “Spain: UN Experts Demand Investigation Into Alleged Spying Programme Targeting Catalan Leaders,” OHCHR, February 2, 2023, www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/02/spain-un-experts-demand-investigation-alleged-spying-programme-targeting.

20 Jonathan Greig, “Zero-Days Exploited in the Wild Jumped 50% in 2023, Fueled by Spyware Vendors,” The Record Media, March 27, 2024, https://therecord.media/zero-day-exploits-jumped-in-2023-spyware.

21 Andy Greenberg, “Hackers Behind the Change Healthcare Ransomware Attack Just Received a $22 Million Payment,” Wired, March 4, 2024, https://www.wired.com/story/alphv-change-healthcare-ransomware-payment; and Josh Taylor, “Shadowy World of Ransomware-for-Hire Revealed by Online Account Activity Linked to the Medibank Hack,” The Guardian, January 27, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2024/jan/28/shadowy-world-of-ransomware-for-hire-revealed-by-online-account-activity-linked-to-the-medibank-hack.

22 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Members of the Intellexa Commercial Spyware Consortium,” March 5, 2024, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2155.

23 United States Department of State, “Announcement of a Visa Restriction Policy to Promote Accountability for the Misuse of Commercial Spyware,” February 5, 2024, https://www.state.gov/announcement-of-a-visa-restriction-policy-to-promote-accountability-for-the-misuse-of-commercial-spyware; and U.S. Department of Commerce, “Commerce Adds NSO Group and Other Foreign Companies to Entity List for Malicious Cyber Activities,” November 3, 2021, https://www.commerce.gov/news/press-releases/2021/11/commerce-adds-nso-group-and-other-foreign-companies-entity-list.

24 The eleven signatories of the Joint Statement are: Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, Denmark, France, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

25 Vanessa Gera, “Poland’s Prosecutor General Says Previous Government Used Spyware Against Hundreds of People,” AP News, April 24, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/poland-spyware-pegasus-nso-group-israel-413bb3cb27daac011d52b524c6d16160.

26 Louise Marie Hurel, Gareth Mott, Aude Géry, Anne-Marie Buzatu, Jen Ellis, Katharina Sommer, Allison Pytlak, and Jérôme Barbier, “The Pall Mall Process on Cyber Intrusion Tools: Putting Words Into Practice,” RUSI, February 20, 2024, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/pall-mall-process-cyber-intrusion-tools-putting-words-practice.

27 Hurel, Mott, Géry, Buzatu, Ellis, Sommer, Pytlak, and Barbier, “The Pall Mall Process on Cyber Intrusion Tools.”

28 “The Pall Mall Process Declaration: Tackling the Proliferation and Irresponsible Use of Commercial Cyber Intrusion Capabilities,” UK Government.

29 U.S. domestic guardrails to curb hacking tools, specifically commercial spyware, include the 2023 Joint Statement; the 2023 Executive Order on Spyware; and the 2024 visa restrictions against individuals connected to the commercial spyware industry. For further reading, see “Joint Statement on Efforts to Counter the Proliferation and Misuse of Commercial Spyware,” The White House, March 18, 2024, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/03/18/joint-statement-on-efforts-to-counter-the-proliferation-and-misuse-of-commercial-spyware; United States Department of State, “Announcement of a Visa Restriction Policy to Promote Accountability for the Misuse of Commercial Spyware,” February 5, 2024, https://www.state.gov/announcement-of-a-visa-restriction-policy-to-promote-accountability-for-the-misuse-of-commercial-spyware; Matthew Miller, “Promoting Accountability for the Misuse of Commercial Spyware,” U.S. Department of State (press release), April 22, 2024, https://www.state.gov/promoting-accountability-for-the-misuse-of-commercial-spyware; and Steven Feldstein, “Biden Cracks Down on the Spyware Scourge,” Foreign Policy, July 31, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/07/31/spyware-nso-cytrox-intellexa-pegasus-predator-biden-sanctions-entities-list-israel-europe.

30 In 2021, the United States added spyware firms NSO Group and Candiru to the Entity List and added Intellexa and Cytrox to the Entity List in 2023. For refence, see United States Department of State, “The United States Adds Foreign Companies to Entity List for Malicious Cyber Activities,” July 18, 2023, https://www.state.gov/the-united-states-adds-foreign-companies-to-entity-list-for-malicious-cyber-activities-2; U.S. Department of Commerce, “Commerce Adds NSO Group and Other Foreign Companies to Entity List for Malicious Cyber Activities,” November 3, 2021, https://www.commerce.gov/news/press-releases/2021/11/commerce-adds-nso-group-and-other-foreign-companies-entity-list.

31 In 2024, the U.S. Treasury imposed sanctions on Intellexa, Cytrox, and other spyware entities and individuals. For further reading see Elias Groll, “U.S. Sanctions Maker of Predator Spyware,” CyberScoop, March 5, 2024, https://cyberscoop.com/predator-intellexa-cytrox-sanctions.

32 Because the United States, France, and the UK, have all signed on to each other’s respective international agreements, there is significant overlap in this category. Cases of international engagement in this category include the 2023 Joint Statement, 2023 Summit for Democracy, 2024 Pall Mall Process, and 2024 Summit for Democracy.

33 Because the United States, France, and the UK, have all signed on to each other’s respective international agreements, there is significant overlap in this category. Cases of international engagement in this category include the 2023 Joint Statement, 2023 Summit for Democracy, 2024 Pall Mall Process, and 2024 Summit for Democracy.

34 Because the United States, France, and the UK, have all signed on to each other’s respective international agreements, there is significant overlap in this category. Cases of international engagement in this category include the 2023 Joint Statement, 2023 Summit for Democracy, 2024 Pall Mall Process, and 2024 Summit for Democracy.

35 DeSombre et al, “Countering Cyber Proliferation.”

36 “The Pall Mall Process: Tackling the Proliferation and Irresponsible Use of Commercial Cyber Intrusion Capabilities,” UK Government.

37 “Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace,” https://parispeaceforum.org/initiatives/paris-call-for-trust-and-security-in-cyberspace.

38 “Cybersecurity Tech Accord,” https://cybertechaccord.org/accord.

39 James Andrew Lewis, “Creating Accountability for Global Cyber Norms,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, February 23, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/creating-accountability-global-cyber-norms.

40 Feldstein and Kot, “Why Does the Global Spyware Industry Continue to Thrive?”

41 Mark Mazzetti, Ronen Bergman, and Matina Stevis-Gridneff, “How the Global Spyware Industry Spiraled Out of Control,” New York Times, December 8, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/08/us/politics/spyware-nso-pegasus-paragon.html; and “How Europe Became the Wild West of Spyware,” POLITICO, October 25, 2023. https://www.politico.eu/article/how-europe-became-wild-west-spyware.

42 Aspen Digital, “A Security Symphony: Harmonizing Cybersecurity Regulation,” May 8, 2024, https://www.aspendigital.org/report/security-symphony.

.jpg)