Over the course of 2024, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the City of Los Angeles convened more than a dozen listening sessions in support of the city’s development of its first-ever Africa Trade and Investment Strategy. The listening sessions brought new voices, perspectives, and geographies directly into the policymaking process. In support of these sessions, select scholars developed exploratory essays on California-Africa connections. These essays are meant to inform policymaking considerations and to identify potential questions for future consideration in developing and examining California-Africa connections. They are at once expert and experimental and attempt not only to shape policy but also to provoke additional scholarship.

Across the world, Silicon Valley is not just the moniker for the greater Bay Area of Northern California. It is also a metaphor for the digital economy at large and a playbook for replicating the success of the Californian ecosystem elsewhere. From the Silicon Plateau of Bangalore to Shenzhen’s Hardware Valley, in alternative geographies of entrepreneurial innovation lessons and models from the Bay Area are borrowed and readapted. In Africa too, these Silicon Valley replicas abound: Lagos hosts Yaba Valley; Nairobi, Kigali, and Kampala are Africa’s Silicon Savannah; Cape Town is the Silicon Cape of the continent. Much more than just branding exercises, these nicknames also capture the aspiration that African tech startups will accelerate economic development, create jobs, and address long-standing issues of poverty and economic marginality. Ultimately, Africa’s innovation hubs articulate the transformative promises of the digital economy. But how did this consensus over the Silicon Valley playbook reach places as different as Accra, Cairo, and Lagos?

To answer this question, this essay reflects on the mobility of what cultural critics Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron famously labeled the “Californian ideology”—a shared belief in the emancipatory promises and possibilities of digital technology.1 The Californian ideology primes Silicon Valley’s narration of itself, but it also travels to unexpected places, including the development field in Africa, where theories and fads from the Bay Area are radically transforming market experiments with anti-poverty practice. Drawing on my work on digital startups that, at once, pledge to unleash wealth and “make poverty history” in Africa (as the mantra goes), this piece charts some of the connections between Californian and African economic life, following mobile ideas about technology and entrepreneurialism.

Crisis of Development

In the fall of 1999, the so-called Battle of Seattle marked a watershed moment for the world of international development—the system of financial assistance that has prescribed economic policies and interventions in the so-called developing world. Students, environmental groups, labor unions, and other grassroots organizations took to the streets of the city to protest a World Trade Organization (WTO) ministerial meeting that was meant to negotiate a number of new free-trade agreements for the new millennium. Less than a year later, demonstrations moved to Washington, DC, on the occasion of the annual sessions of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Even though protesters had gathered under the banner of the anti-globalization movement,2 their critiques ultimately addressed these Bretton Woods development organizations.

The demonstrators argued that development, the way it had been done by the IMF and the World Bank, had served the interests of Western corporations and had done little to lift people out of poverty. This view echoed the broader point that critical scholars of development had made for some time: aid money flowing into infrastructure projects and tied to structural adjustment (privatizations and cuts in state spending) had not worked, especially in Africa. If anything, development had made poverty a matter of technical rather than political intervention.3 Scholars were not alone in their critiques of development. Already in April 1980, several African leaders had met on the Nigerian coast under the auspices of the Organization of African Unity, a precursor to the African Union, and collectively drafted the Lagos Plan 1980–2000.4 Couched with dependency theory—in short, an interpretation that underdevelopment was convenient to wealthier economies in the core of the global capitalist system—the plan was a public rejection of fiscal policies that would later become known as structural adjustment and a call for delinking African economies from the prescriptions of the Bretton Woods system.

The World Bank’s response to the Lagos Plan in the 1980s—best captured in the Berg Report5—doubled down on structural adjustment, but by the 2000s, this was no longer possible. A new paradigm was necessary, and both development organizations and so-called developing nations embraced a philosophy of individual empowerment through entrepreneurship.6 Even though many aid programs continued as usual, a new consensus formed around the idea that more entrepreneurial forms of development were best suited to address the predicaments of the postcolonial world. Microfinance provided the most celebrated example: if poor people, especially poor women, were seen as entrepreneurs worthy of financial assistance, then they could be helped to help themselves, and, in turn, foster economic growth.7 This approach dovetailed with the writings of influential economists like Hernando de Soto and C. K. Prahalad, who, in different ways, advocated for the recognition of informal economies as cradles of frugal innovation and entrepreneurial potential.

Ultimately, the crisis of traditional development practice inaugurated a period of new market experiments in the Global South, and in Africa in particular. As anthropologists Catherine Dolan and Dinah Rajak write, these experiments reflected “a shift in the wider development industry from the grand schemes of macro‐economic restructuring and social transformation that once animated national dreams of modernity, to the entrepreneurial individual as the catalyst to human improvement and national growth.”8 One question, however, remained to be answered. If development were to shift from infrastructure projects and macroeconomic policy to empowering entrepreneurs, what tools, techniques, and technologies might be needed to train people in Africa as entrepreneurs? To help them help themselves? While economists like de Soto, Prahalad, and others had their own answers, another rejoinder came from an unexpected place: sunny, boisterous Silicon Valley.

Californian Ideology and Airborne Devices

Just as the industry of development experienced its own crisis of legitimacy at the turn of the millennium, Silicon Valley too had gone through its own waves of crisis and resurgence, first in the late 1970s,9 and again in the early 2000s, with the dotcom bubble and subsequent bust that wiped out many promising software companies. Throughout this time, a collective myth of belonging and resilience emerged as one of the identities of Silicon Valley. This was “the Californian ideology,” a unique blend of countercultural utopianism and free-market libertarianism.10 Elites from the Bay Area promoted a view of the world that “promiscuously combine[d] the free-wheeling spirit of the hippies and the entrepreneurial zeal of the yuppies.” At the core of it was the supposed liberatory power of technological advancement and its capacity to fix social ills. More recently, this technological optimism has been termed “techno-solutionism.”11

One of the forefathers of this ideology was futurologist Alvin Toffler, who built ideological bridges between California and Washington, DC, when his mentee Newt Gingrich rose to speaker of the house in the mid-1990s. More than a decade earlier, Toffler had skillfully captured the zeitgeist of the early Silicon Valley days in The Third Wave, a book that theorized human evolution across three waves of radical change, the last of which, paired with the inevitable obsolescence of the state in the Information Age, was the ultimate end of technological advancement. In one of the most discussed chapters of The Third Wave, Toffler argued that connectivity technologies would allow poorer countries to “leapfrog,” meaning to skip the industrialization phase and jump right into the Information Age. To conjure this vision, Toffler described airborne devices that would bring connectivity to rural, remote parts of the underdeveloped world. Fast forward almost forty years, these futuristic, aethereal imageries became a real developmental project, with Google’s helium-filled balloons bringing broadband internet to rural Kenya and other landlocked regions in Africa.12

But aside from these anecdotal parallels, which are almost a caricature of the ways in which the Californian ideology—quite literally—lands in Africa, there are other important reasons why Silicon Valley’s cultures of entrepreneurialism worked well for the development sector in Africa, at a time when other models of intervention were questioned. Up until recently, as I have previously argued, neoclassical theories of static efficiency dominated the field of development.13 With few exceptions, economists had little to say about entrepreneurs.14 And they offered even less about how to turn ordinary people into incipient, risk-taking, job-creating businesspeople. Therefore, when the development industry shifted its focus to entrepreneurial empowerment as a catalyst of economic growth and anti-poverty, experts did not have much theory to turn to, aside from the doctrines of neoliberal economists like de Soto. Meanwhile, Silicon Valley evangelists had developed their own canon of writing and thinking about what makes an entrepreneur. These works did not constitute a full-fledged theory,15 but they consisted more of a constellation of managerial fads, self-help books, how-to guides, and other reflexive manuals which, as a whole, made the point that entrepreneurialism is not innate but needs to be nurtured and cultivated.

In other words, the techno-optimism emanating from Silicon Valley has reached the world of African development in two interrelated ways. On the one hand, technology itself seems to have the power to solve impossible quandaries. From solar lamps to water-purifying straws, from the boxy computers of the One Laptop Per Child program16 to Google’s balloons, these “little development devices”17 hold the promise of fixing broken systems in domains purportedly dominated by chronic state failure across the continent and beyond. On the other hand, coupled with the technological solutions are scores of potential African entrepreneurs (and state planners) that could be trained using the same knowledge mechanisms that produced several generations of Californian startups and tech giants. A good example is the World Bank itself. In 2017, the development institution launched a pan-African pilot accelerator, XL Africa, to scale up high-growth digital startups that were providing critical services and generating revenue while creating employment. In a nutshell, the World Bank copied the model offered by the venture capital firm Y Combinator—which seeded well-known platforms like Airbnb, Reddit, and other tech giants from the Bay Area—to foster developmental digital companies that, just like solar lamps, were meant to do well (generate revenue) while doing good (creating jobs) in Africa.

Of course, the Californian ideology has pitfalls: for one, it is often conveniently blind to the hidden costs and racialized pasts of Silicon Valley capitalism.18 Moreover, this libertarian ideology is also willfully ignorant of the role that the U.S. state budget played in the global ascendancy of Silicon Valley as the world’s technology capital.19 But this ideology, with its tech-infused entrepreneurial optimism, mantras, and techniques, has still transformed and influenced developmental economic experiments in Africa.

Running Lean in Africa

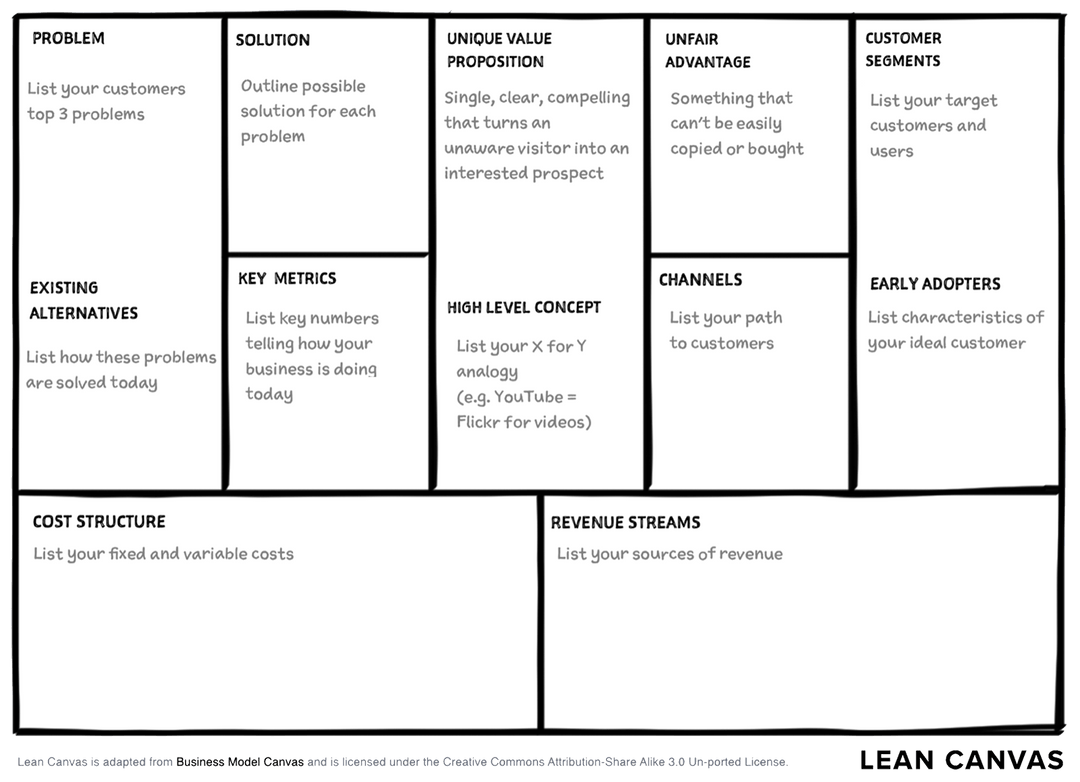

During my early research in Cape Town, I encountered a self-trained tech entrepreneur who slept every night with a copy of Ash Maurya’s Running Lean on his nightstand. Inside the book, he kept a folded printout of the “lean canvas,” a template that allows entrepreneurs to apply the so-called lean method to their own companies (see figure 1). He had filled out each box of the template and kept returning to it as he dreamt of the hopeful future of profit and social change that his startup manifested.

Both Running Lean and the lean canvas are offshoots of the publishing machine initiated in 2008 by Eric Ries, who has since trademarked the concept of “lean startup” and become a best-selling author through the eponymous volume. An entrepreneur and investor himself, Ries is among the best-known evangelists of the post-dot-com-burst Californian ideology. Specifically, through lean startup, Ries gave a name to a trend that had informed almost a decade of new Silicon Valley companies emerging from the ashes of the tech bubble. Borrowing a term that had been used by management scholars to describe the differences between Toyota’s just-in-time production system (lean) and Fordist mass production, Ries highlighted a shift in the approach of new digital ventures. As Toyota’s production manager Taichi Ohno had done in the twentieth century, post-dot-com-boom startups had recognized the need to better understand and track their mistakes and their customers.

Figure 1. Lean Canvas Worksheet

Source: Lean Canvas is adapted from Business Model Canvas and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Un-ported License.

Through a number of case studies, Ries offered a how-to manual for fledgling entrepreneurs wishing to “turn ideas into products, measure how customers respond, and then learn whether to pivot or persevere.”20 In particular, Ries explained, the keys to a successful venture were the constant experimentation and the careful measurements of each step, especially through real-life pilots. From customer interviews to prototyping protocols, Ries and his acolytes, including the author of Running Lean, developed a gamut of techniques that were meant to help the startup journey of willful entrepreneurs. These techniques have traveled the world of digital startups everywhere, but their reach goes even further. Increasingly, they have been adopted by humanitarian NGOs, developmental organizations, cooperatives, and social enterprises. After all, the lean startup closely aligns with the practical need to foster entrepreneurial capabilities at both organizational and individual levels.

A whole industry of lean development consulting has germinated from the lean startup approach.21 Consultants, experts, and angel investors use these methods for all kinds of training. They teach NGOs how to prototype technological solutions, how to test user experience, how to validate financial assumptions, and how to garner data about the entire process. At InfoDev, the World Bank’s platform for supporting small innovators in Africa and other Global South regions, the lean startup is an official part of the curriculum. Entire master classes are designed to teach the lean approach to African government officials. And beyond the experts and the evangelists, the lean books are available to everyone with an internet connection. Templates can be downloaded. The lean grammar is a shared language: a Kenyan social entrepreneur can present their minimum viable product (MVP) without doubting that a Silicon Valley impact investor knows exactly what an MVP is.

But why is the lean startup approach so powerful in the domain of development and beyond the more restricted field of digital entrepreneurship? From one angle, it is easy to see how these lean methods perfectly match the need to produce capable entrepreneurs who may churn out useful technological solutions and create jobs where there is a dire need for both. Yet, from another angle, the lean startup also responds to the desire to conscientiously assess—through randomized control trials—whether development interventions yield results in the first place. This experimental approach has been championed by many, but in particular by Abhijit Banerjee and Ester Duflo, two of the founders of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), an organization that administers metric-based tests to evaluate if poverty-reduction initiatives, whether undertaken by the World Bank or the private sector, meet their goals. “We need evidence,” they explained,22 and a few years later they went on to receive the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. Their approach consists of selecting control groups and gathering accurate data about poverty alleviation experiments.

In other words, the lean startup and the J-PAL methods are remarkably aligned, even though they come from different fields. Over many years of research, I have encountered several organizations and startups that were trying to combine these two models to deliver profit and social good.23 The lean startup, in their view, was a way of operationalizing the experimental ethos of randomized trials and tracking their impact. As I have previous written, “both approaches advocate metrics-driven, real-life pilots. Both remark on the importance of understanding failures and pivoting before it is too late. Both approaches are also predicated on a critique of technocracy. While Banerjee and Duflo address the top-down perspective of development bureaucrats, Ries addresses the technocentric mindset of software developers who do not understand future users.”24 And lastly, as the next section outlines, both the lean startup and the J-PAL experiments are ultimately informed by the developmental promises of behavioral economics.

Entrepreneurial Nudges

Behavioral economics, and the behavioral sciences more generally, have had a long and fraught relationship with digital technology. The birth of modern computing and the desire to model and influence social behavior through predictive algorithms are inextricably tied to the winding history of experiments that runs from Cold War science to the consulting firm Cambridge Analytica.25 Behaviorists recognize that the key assumption of neoclassical economics—rational, individual decisionmaking—is fiction and that economic life teems with social-cognitive biases. Understanding and measuring these biases, and therefore acting upon them, are fundamental activities to create profitable markets. And with digital technology offering unprecedented troves of data about how so-called target populations behave, modeling human behavior is not a distant dream any longer.

One particular avenue through which behavioral economics has found its way to Silicon Valley is the application of so-called nudge theory to the design and development of digital products and services.26 Popularized by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein,27 nudge theory is a practical application of behaviorism to effect changes in social and individual patterns, not through imposition but through tweaks in the “architecture of choice”—whether in consumer marketing or policymaking. Nudge theory, in many ways, is rife with echoes of Californian ideology. Not only is it predicated on similar libertarian ideals, but also, it is fundamentally a techno-solutionist approach. Unsurprisingly, nudge theory has many champions in Silicon Valley and has found applications way beyond the imperative of nudging customers. For example, Ries’s follow-up book after The Lean Startup, The Startup Way,28 is a manual for big tech companies to nudge decisionmaking as an internal organizational practice.

Ultimately, just like the lean startup, this Californian version of nudge theory too has traveled to the seemingly distant sphere of African development. A turning point was the World Bank’s World Development Report 2015: Mind, Society, and Behavior.29 In the report, the bank takes stock of its many years of suboptimal results in anti-poverty programs and argues that better interventions can be designed through a more subtle view of human behavior; less neoclassical economics, more nudge theory, the authors of the report argue. After all, “behavioral economics reveals that . . . poor people make mistakes that end up making them poorer, sicker, and less happy,”30 and therefore making minor adjustments that alter the choice architecture is an effective strategy to help the poor help themselves. Not incidentally, this theory posits these small adjustments, as well as their effectiveness, can be gauged and monitored through randomized control trials like those advocated by J-PAL—even better if the adjustments have a digital component, since data become easier to capture.

As a result, a plethora of nudge theory–inspired experiments have proliferated in Africa.31 Combining the evidence-based ethos of randomized anti-poverty trials with faith in the emancipatory power of digital technology, these experiments have shifted development practices toward behavioral coaxing. And this is not, of course, just limited to humanitarian aid. Increasingly so, nudge theory informs the business models of tech startups that, by promising to address environmental and social issues, seek to access the trail of development finance as a springboard to more sustained venture capital investments.

For example, my colleagues in Cape Town, Kigali, and Nairobi and I observed the deployment of nudge techniques in the platformization of motorcycle taxis, a crucial urban economy across African cities.32 Motorcycle taxi operators (called riders) provide a lifeline for the movement of people and goods in the absence of public transport and more capillary logistics operators (see figure 2).33 One telling case study is the use of pay-as-you-go (or pay-go) technologies in the financing of the transition to electric bikes. E-bikes (or the batteries that power them) are expensive assets, and riders in urban Africa rarely have sufficient capital to acquire such costly vehicles or to retrofit their existing ones. Nor do they have access to traditional forms of asset financing, since getting a loan requires credit scores and stable incomes—neither of which are commonly available to informal workers like motorcycle taxi riders. For these reasons, there is an ever-growing number of startups that apply pay-go devices to electric vehicles. Through these systems, riders pay back their e-bikes in small daily installments. Without a daily payment, the bike does not even turn on: users are coaxed into careful, everyday savings, just like the famous penny-in-the-slot meter did with early twentieth-century working classes in the West.34 And the nudges do not stop there. Pay-go technologies are, after all, Internet of Things devices that can track many other aspects of drivers’ behaviors. These startups nudge their riders to respect speed limits, wear helmets, work certain amounts of hours, and stay within certain geographic boundaries, among other behaviors, in an overall attempt at derisking the transition to green mobility (though such a transition is not without contradictions).35

Looking beyond, for a moment, the many problems related to pay-go technologies (which often turn out to be predatory credit schemes), these startups also ultimately show the pervasiveness of Californian ideology–infused experiments through which startups in Africa create data-rich environments to create profit while, purportedly, improving existing industries, decarbonizing urban economies, and addressing issues of poverty. Pay-go schemes for green motorcycle taxis are, in my reading, the ultimate example of the “solutionism” of the Californian ideology in Africa: a rush to digital experiments that cast developmental problems as opportunities for profitable startups and recast the former developing world not as a destination of technological transfer but as a living lab of innovation.36

Figure 2. Motorcycle-taxi riders waiting for their next gig in Nairobi, Kenya. (Author’s photo)

Thinking Through Circulations of Ideas

This essay has examined how certain ideas and models of social change, informed by a California-inspired technological optimism, reach the world of development and anti-poverty in Africa. These ideas rest on the belief that innovation, entrepreneurialism, and even technology itself may fix the fractures of a world scarred by colonial injustice and unequal relations of economic power. Ultimately, even when or if observers are critical of some of their assumptions, managerial and behavioral theories have also a life of their own, circulating and being transformed as they are applied and experimented. New relationships between places, new alliances, and shared grammars form out of these mobilities. In turn, I would argue, these connections offer a vehicle for thinking about the inextricable lattice of relations that already exist between geographies that seem to have little to do with each other. More importantly, such existing linkages are also an avenue for researchers, policy planners, consultants, activists, entrepreneurs, and other observers to reflect propositionally about the stakes and the possibilities of these connections.

Acknowledgements

A small portion of this essay has appeared in another paper and has been readapted for this essay. Thank you, Liza Cirolia and Ian Klaus, for reading and thinking together.

Notes

1 Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, “The Californian Ideology,” Science as Culture 6, no. 1 (1996): 44–72, accessible at https://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/californian-ideology.

2 Julia Elyachar, “Empowerment Money: The World Bank, Non-governmental Organizations, and the Value of Culture in Egypt,” Public Culture 14, no. 3 (2002): 493–513.

3 James Ferguson, The Anti-politics Machine: “Development,” Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho (University of Minnesota Press, 1994).

4 Lagos Plan of Action for the Economic Development of Africa, 1980–2000, Organization of African Unity, 1980, https://web.archive.org/web/20070106003042/http://uneca.org/itca/ariportal/docs/lagos_plan.PDF.

5 Accelerated Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Agenda for Action (Washington, DC: World Bank Group), https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/702471468768312009/accelerated-development-in-sub-saharan-africa-an-agenda-for-action.

6 Ben Fine, “The Developmental State Is Dead—Long Live Social Capital?," Development and Change 30, no. 1 (1999): 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00105.

7 Ananya Roy, “Subjects of Risk: Technologies of Gender in the Making of Millennial Modernity,” Public Culture 24, no. 1 (2012): 131–155, https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-1498001.

8 Catherine Dolan and Dinah Rajak, “Speculative Futures at the Bottom of the Pyramid,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 24, no. 2 (2018): 236, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12808.

9 AnnaLee Saxenian, “Regional Networks and the Resurgence of Silicon Valley,” California Management Review 33, no. 1 (1990): 89–112, https://doi.org/10.2307/41166640.

10 Barbrook and Cameron, “The Californian Ideology.”

11 Evgeny Morozov, To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism (PublicAffairs, 2014).

12 Bethlehem Feleke, “Google Launches Balloon-Powered Internet Service in Kenya,” CNN, July 8, 2020, https://edition.cnn.com/2020/07/08/africa/google-kenya-balloons/index.html.

13 Andrea Pollio, “Acceleration, Development and Technocapitalism at the Silicon Cape of Africa,” Economy and Society 51, no. 1 (2022): 46–70, https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2021.1968675.

14 For exceptions, see Maria T. Brouwer, “Weber, Schumpeter and Knight on Entrepreneurship and Economic Development," Journal of Evolutionary Economics 12 (2002): 83–105, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-002-0104-1.

15 Nigel Thrift, Knowing Capitalism (Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 2005).

16 This program can be found at https://laptop.org.

17 Stephen J. Collier, Jamie Cross, Peter Redfield, and Alice Street, “Little Development Devices/Humanitarian Goods,” Limn 9 (2017).

18 Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

19 Mariana Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs Private Sector Myths (Penguin Books, 2024).

20 Eric Reis, The Lean Startup (New York: Crown Business, 2011), 18.

21 Pollio, “Acceleration.”

22 Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee, Poor Economics (New York: Public Affairs, 2011), 4.

23 Andrea Pollio, “Reading Development Failure: Experts and Experiments at the Bottom of the Pyramid in Cape Town,” Third World Quarterly 42, no. 12 (2021): 2974–2992, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1983425. Of course, the idea that profit and social good can be pursued at once has many different genealogies, including the thinking of Adam Smith in The Theory of Moral Sentiments.

24 Pollio, “Acceleration, Development and Technocapitalism at the Silicon Cape of Africa.”.

25 Jill Lepore, If/Then: How the Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future (Liveright Publishing, 2020).

26 Elif Buse Doyuran, “Nudge Goes to Silicon Valley: Designing for the Disengaged and the Irrational,” Journal of Cultural Economy (2023): 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2023.2261485.

27 Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008).

28 Eric Ries, The Startup Way: How Modern Companies Use Entrepreneurial Management to Transform Culture and Drive Long-Term Growth (New York: Currency, 2017).

29 World Development Report 2015: Mind, Society, and Behavior (Washington DC: The World Bank, 2014), https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2015.

30 Christian Berndt and Marc Boeckler, “Behave, Global South! Economics, Experiments, Evidence,” Geoforum 70 (2016): 22–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.01.005.

31 Kevin P. Donovan, “The Rise of the Randomistas: On the Experimental Turn in International Aid,” Economy and Society 47, no. 1 (2018): 27–58, https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2018.1432153.

32 Liza Rose Cirolia, Rike Sitas, Andrea Pollio, Alexis Gatoni Sebarenzi, and Prince K. Guma, “Silicon Savannahs and Motorcycle Taxis: A Southern Perspective on the Frontiers of Platform Urbanism,” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 55, no. 8 (2023): 1989–2008, https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X231170193.

33 Andrea Pollio, Liza Rose Cirolia, and Jack Ong'iro Odeo, “Algorithmic Suturing: Platforms, Motorcycles and the ‘Last Mile’ in Urban Africa,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 47, no. 6 (2023): 957–974, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.13200.

34 Antina Von Schnitzler, “Traveling Technologies: Infrastructure, Ethical Regimes, and the Materiality of Politics in South Africa,” Cultural Anthropology 28, no. 4 (2013): 670–693, https://doi.org/10.1111/cuan.12032.

35 Rike Sitas, Liza R. Cirolia, Andrea Pollio, Jack O. Odeo, Alexis Gatoni Sebarenzi, and Alicia Fortuin, Platform Politics and Silicon Savannahs: Fintech and the Platformed Motorcycle: Speculating on Ordinary Mobility Economies in Urban Africa (Cape Town: African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town, 2023).

36 Adam Moe Fejerskov, The Global Lab: Inequality, Technology, and the Experimental Movement (Oxford University Press, 2022).