Climate change impacts are felt worldwide, manifesting in diverse ways across different regions. Jordan, too, has experienced intensified and more frequent heatwaves, flash floods, droughts, and associated health issues due to climate change. This article aims to unveil evidence-based vulnerabilities and risks to climate change in urban areas within Jordan, focusing on its capital, Amman.

Jordan has joined 195 countries in adopting the Paris Agreement’s goal to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.” Recently, it has been agreed that the threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius (°C) should be targeted until 2100.

Cities and local governments are at the front line of tackling climate change and achieving progress toward keeping the global temperature below 1.5°C. Their efforts have evolved around mitigation and adaptation measures. Amman, a highly urbanized capital, faces environmental challenges and climate vulnerabilities. This piece highlights Amman’s issues and explores how this middle-income city in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region articulates its policies in responding and adapting to the climate crisis.

To do so, it utilizes vulnerability mapping to assess the projected vulnerability and impact of climate hazards—such as heatwaves, flash floods, droughts, and diseases—across Amman’s twenty-two districts. It focuses on the adaptation measures the city needs. This approach helps the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM) prioritize adaptation projects and allocate budgets for localized climate change interventions. Enhancing the city’s climate resilience stands as a crucial response to the climate change crisis, enabling more effective policies, action plans, and engagement with vulnerable groups while safeguarding natural resources and bolstering urban resilience against climate impacts.

The Socioeconomic and Environmental Context of Amman City

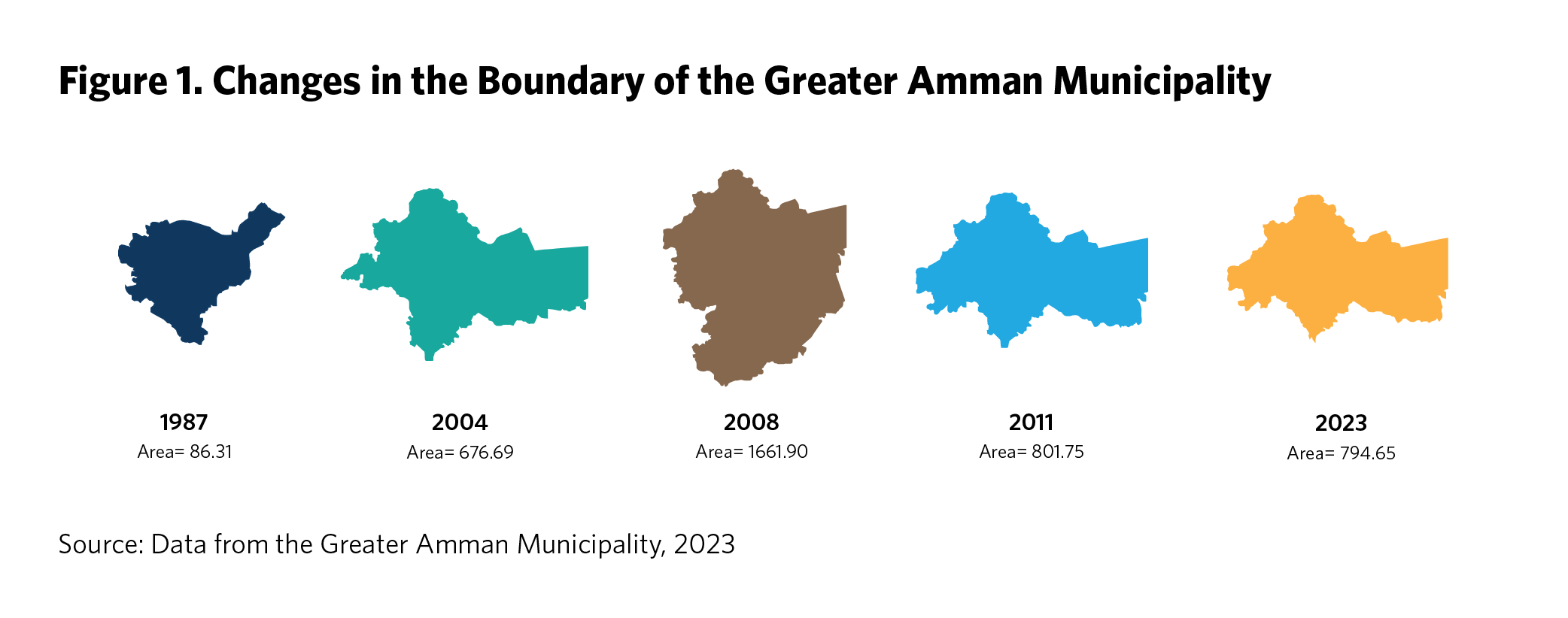

The capital city of Jordan, Amman, has witnessed exponential change in its demographic, social, and economic context. Since the GAM was founded in 1987, the city has expanded nine times from 86.31 square kilometers (km2), to reach 794.65 km2 in 2023, as illustrated in figure 1.

The population of Amman has grown rapidly, reaching 4,642,000 in 2021, stemming from natural population growth, an exodus from rural areas, and a high influx of refugees and migrants seeking jobs. Women make up 46.3 percent of Amman’s population. People with disabilities account for 10 percent of Amman’s population. The average household size in Amman is 4.6 persons. The Jordanian community is known to be youthful, where 40.81 percent of the population are younger than nineteen years old and only 4.2 percent are above sixty-five years old.

Amman has witnessed multiple trends that exacerbate the city’s systems and citizens’ vulnerability to climate challenges. Urbanization is among the most pressing challenges correlated to the climate crisis. It has put significant and unprecedented pressure on the city’s aging infrastructure; widened the institutional, resources, and preparedness gaps; and decreased citizens’ institutional trust. Amman’s political and economic status drives internal migration from other Jordanian cities, specifically rural areas where people are in search of better services and livelihood opportunities. Consequently, about 40 percent of Jordan’s population resides in the capital city. It is the country’s most urbanized city, with an urbanization rate of 97.2 percent and a population density of 612.5 persons/km2. The protracted crisis in the region and the consequent high influx of refugees has played a central role in the unforeseen population growth of Amman. The number of refugees hit 193,781 in 2020. At the same time, a 24 percent unemployment rate in the city contributes to rising vulnerabilities to the climate crisis.

Urban sprawl, inefficient urban planning, and poor land use management have significantly exacerbated climate challenges. It is worth noting that both the first growth plan developed in 1987 and the 2008 Amman growth plan called for protecting agricultural areas from urban encroachment. The GAM developed the first comprehensive plan for Amman City in 1987, unveiling the city’s growth plan until 2005. However, the city boundary was 86.31 km2 in 1988; currently, it covers 794.65 km2.[1] The city government’s massive investment in developing road infrastructure for the past three decades, focusing on vehicle needs more than people-centric planning, has turned Amman into a car-dependent city, with rising levels of air pollution and a deteriorated public transport system.

The availability of green spaces in Amman is a protracted challenge. Urban encroachment on agricultural lands in Amman has affected the quantity and quality of green elements in the city. Despite the city’s efforts to increase the green infrastructure in Amman, until 2022, it accounts for only 1.768 percent of the city’s area, whereas 3.18 square meters (m2) is the per capita share. The city aims at increasing the per capita share by the end of 2026 to reach 4.3 m2.

Amman has a semiarid climate, situated within the northern central highlands of Jordan, which received 197.3 cubic millimeters precipitation in 2016–2017. A total of 42 percent of Amman is built, while 30 percent is bare soil, and 13 and 11 percent accommodate fertilized agricultural lands—rainfed crops and orchards—and grasslands, respectively. The city has complex topography that spans from 82 meters to 1,108 meters above sea level. This variation in the terrain gives a unique climate characteristic to each district, where high districts perceive high precipitation, have cooler weather in summer, and have better vegetation coverage. According to Jordanian standards, Amman has good ambient air quality. However, the human footprint, such as industrial activities, transport, and the irresponsible consumption of fossil fuel, concentrate the fine particles of PM2.5 in the air that has had a deteriorating effect on the environment.

Despite Jordan’s high-water stress, 99 percent of the drinking water quality in Amman meets the national standards. Up through 2020, the number of water-related illnesses significantly declined, according to the Ministry of Health Statistical Report 2022. All citizens have access to safe sewage disposal systems: 76 percent of the city is covered with a sewage network, while the rest connect to local septic tanks.[2] Amman has three wastewater treatment plants, from which the treated water is used not for drinking but for irrigation and industrial activities. However, water accessibility will be threatened by not only overexploitation but also climate change.

Historical Impact of Climate Extremes

Climate hazards have serious environmental, economic, health, and social consequences. They can exacerbate the vulnerability of people, city systems, and assets. The most prominent climate hazards that Amman experiences are heatwaves, drought events, flash floods, and air- and vector-borne diseases. To better understand the implication of each hazard, it is worth reflecting the definition of these hazards in the Jordanian context. The World Meteorological Organization and the World Health Organization define heatwaves as “periods of unusually hot and dry or hot and humid weather that have a subtle onset and cessation, a duration of at least two to three days and a discernible impact on human activities.” In the past two decades, Amman witnessed three heat waves: in 2000 and 2010 exceeding a threshold of 40°C, with the highest reaching 43.5°C, over eight continuous days. The most recent heatwave, which hit the city in 2020 and persisted for eleven consecutive days, recorded a high of 43°C.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines drought as “a period of abnormally dry weather long enough to cause a serious hydrological imbalance.” As per Jordan’s Fourth National Communication Report (4NC), Jordan has experienced periodic drought events throughout its history, which, coupled with increased demands from population and economic growth, have exacerbated its water-stress level, reaching 104.31 percent in 2020. Drought events in Jordan are characterized by below-average precipitation and declining water levels in surface and groundwater resources.

These events have profound implications on the rapidly growing, densely populated city. Water shortages detected through intermittent water supply, and increased water prices, have affected socioeconomic vulnerabilities and the well-being of residents. Leakages and defective metering systems in Amman’s aging water infrastructure have created nonrevenue water, further contributing to water challenges.

During the past decade, Amman had witnessed intense rainfall events that have caused flash floods, especially in lower-lying areas of the city such as Al Madinah District. Factors contributing to these flash flood incidents include urban sprawl over natural water streams, population growth putting pressure on the poorly maintained stormwater infrastructure, insufficient green areas, and wide areas of impermeable asphalted surfaces hindering the infiltration of rainfall into the groundwater. For three consecutive years, starting in 2013, Amman experienced severe flash floods that caused deaths and damaged infrastructure and assets. Earlier, a destructive flood hit the city in 2019, not only affecting people and properties and increasing the financial burden on the greater municipality but also harming the city’s heritage—the flooding sank the archaeological site of a Roman theatre in downtown Amman.

Over the past five years, citizens have detected extraordinary spread of insects and related diseases. Leishmaniasis, a vector-borne disease transmitted through sand fly bite, is highly connected to climate extremes, especially rising temperatures and heat waves. German and American cockroach spread, which is interconnected with rising temperatures, can transmit foodborne diseases. Insect outbreaks, such as ground and bark beetles and termites, also have been observed.

The exponential deterioration of air quality in Amman has contributed to rising cases of airborne and respiratory diseases as the concentration of PM2.5 rises and the city has limited greenery to purify the environment. Asthma and respiratory system allergies are among the most highly observed cases, especially in toddlers and adolescents. As per the World Health Organization, in 2019, the spread of ischemic heart disease; trachea, bronchus, and lung cancers; lower respiratory infections; stroke; and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are attributable deaths of ambient air pollution.

Local Climate Governance: Amman Roadmap for Climate Action

Jordan endeavors to be a “resilient low-carbon nation” by 2050. Aligning with its Economic Modernization Vision and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change objectives, the kingdom has recently developed the National Adaptation Plan (2021) and Climate Investment Mobilization Plan, in addition to updating three national climate policies: the National Climate Change policy (2022–2050), Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) (2021), and the 4NC. The updated NDCs show the country’s new target in raising its macroeconomic greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction target from 14 percent in the first NDC to 31 percent, focusing on five sectors—energy, transportation, industrial processes and product use, waste, and agriculture—with an estimated cost of $7.54 billion. The NDC on adaptation addresses measures on water resource management, agriculture and food security, biodiversity and ecosystems, health, urban resilience and disaster risk reduction, coastal zone management, and cultural heritage and tourism.

Since 2017, the city has developed strategies and action plans responding to climate change, marking a paradigm shift in the GAM’s commitment to the issues. It has aligned its efforts with Jordan’s commitment to Paris Agreement, limiting the average global temperatures to well below 2°C, in addition to achieving progress toward the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Some of these plans are given below.

- The Amman Resilience Strategy has paved the way for Amman’s progress toward a multisectoral, systematic, and actionable strategy that will build a city more resilient to multiple shocks, including climate-related ones. Comprising five pillars, the strategy aligns five goals under “an environmentally proactive city” pillar, addressing Amman’s climate change commitments endorsed during COP21 and C40 Cities actions, energy resources diversification, green buildings, water resources management, and municipal solid waste management. It encompasses 16 goals and 54 actions. Building on this strategy, Amman adopted its first Climate Action Plan (CAP) in 2019, envisioning ambitious targets until 2050 for reducing GHG emissions and building climate resilience through six sectoral pillars: renewable energy, water and wastewater, transport, buildings, solid waste management, and urban planning. The action plan has 21 goals and 51 actions.

- The Amman Green City Action Plan is an updated evidence-based roadmap, based on the city’s environmental challenges and priority sectors, to guide the city’s transition toward a more sustainable future. It outlines a comprehensive range of 64 short- and long-term actions and initiatives under 19 goals, responding to key sectors: energy systems and buildings, urban mobility (including pedestrian network and public transportation), solid waste management, water resource management, land use planning, and climate adaptation policies.

- The Amman Smart City Roadmap has five pillars: smart environment, smart public, health, smart public safety, smart energy, and smart mobility. It intends to achieve 11 smart projects.

- Amman’s Voluntary Local Review (2022) has also measured and reported the city’s progress on SDG 13 of Climate Act, calling for “urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.” It supports the city’s GHG emissions reduction and builds its resilience to climate shocks and adaption of infrastructure as renewable energy, water and wastewater management, and green buildings.

- The new GAM Strategic Plan (2022–2026) has built a five-year strategy while addressing climate change as a priority for the city. Climate action is embedded within GAM units and departments. It shows the multilevel climate act through 212 projects around 30 goals.

- The city is at the final stages of releasing the updated Amman Climate Action Plan. By applying the C40 CAP Framework, the GAM aims at expanding climate change adaptation and disaster risk management and mainstreaming climate change mitigation and adaptation across all GAM’s operations. The 2023 plan reflects the evolving contexts of urbanization, high population, and development projects. It addresses the gap in achieving targets of 32.4 percent of GHG emissions reduction through ongoing and proposed actions by 2030. It aligns with national and local strategies such as the National Climate Change Policy (2022–2050), the Long-term Low-carbon and Climate Resilient Strategy for Jordan, and Jordan’s Economic Modernization Vision, as well as the GAM Strategy (2022–2026).[3]

- In parallel with the new Amman Climate Action Plan, the GAM has conducted a Climate Change Risk Assessment for Amman City, a spatial district-level assessment that gives the city a comprehensive overview on the likelihood and magnitude of climate hazards on the city’s districts. It positions Amman’s action plan at the core of climate adaptation.

Projected District-Level Vulnerabilities to Climate Hazards

How vulnerable is Amman City to climate hazards? What is Amman’s districts’ vulnerability to heat waves, flash floods, and airborne and vector-borne diseases?

Amman City has considered climate-related challenges through the Amman Metropolitan Growth Plan by developing a comprehensive master plan that rethinks urban planning and built environment challenges. It plays a pivotal role in responding to urban sprawl and population growth in the city sustainably and resiliently. The plan encompasses multiple approaches to tackle the impact of urbanization and accompanied environmental challenges such as the urban heat island effect, natural resources depletion, air pollution, floods, and water scarcity. The municipality has identified energy, municipal solid waste, water and wastewater, transport, and urban planning as sectors prominently contributing to climate change risk in the city.

The GAM conducted evidence- and scientific-based climate change vulnerability and risk assessment for Amman City, as per the C40 CITIES Climate Leadership Group requirement, following the Climate Change Risk Assessment Guidance. It aims to understand better and align its policies, strategy, and climate action plans and devote resources to confront climate change impacts at the district level. The evidence-based assessment paves the way for Amman City to localize district-level climate action. It assists the city in mobilizing resources to a specific, accurate, and targeted action plan. The GAM aims to align its policies, strategy, and climate action plans and to devote resources to confront climate change impact at the district level.

Although heatwaves, droughts, and flash floods have been widely observed and studied in the city, air- and vector-borne diseases are less studied, though they are highly correlated to climate change and the emergence of public health concerns in Amman.

Amman’s District-Level Vulnerability to Heatwaves

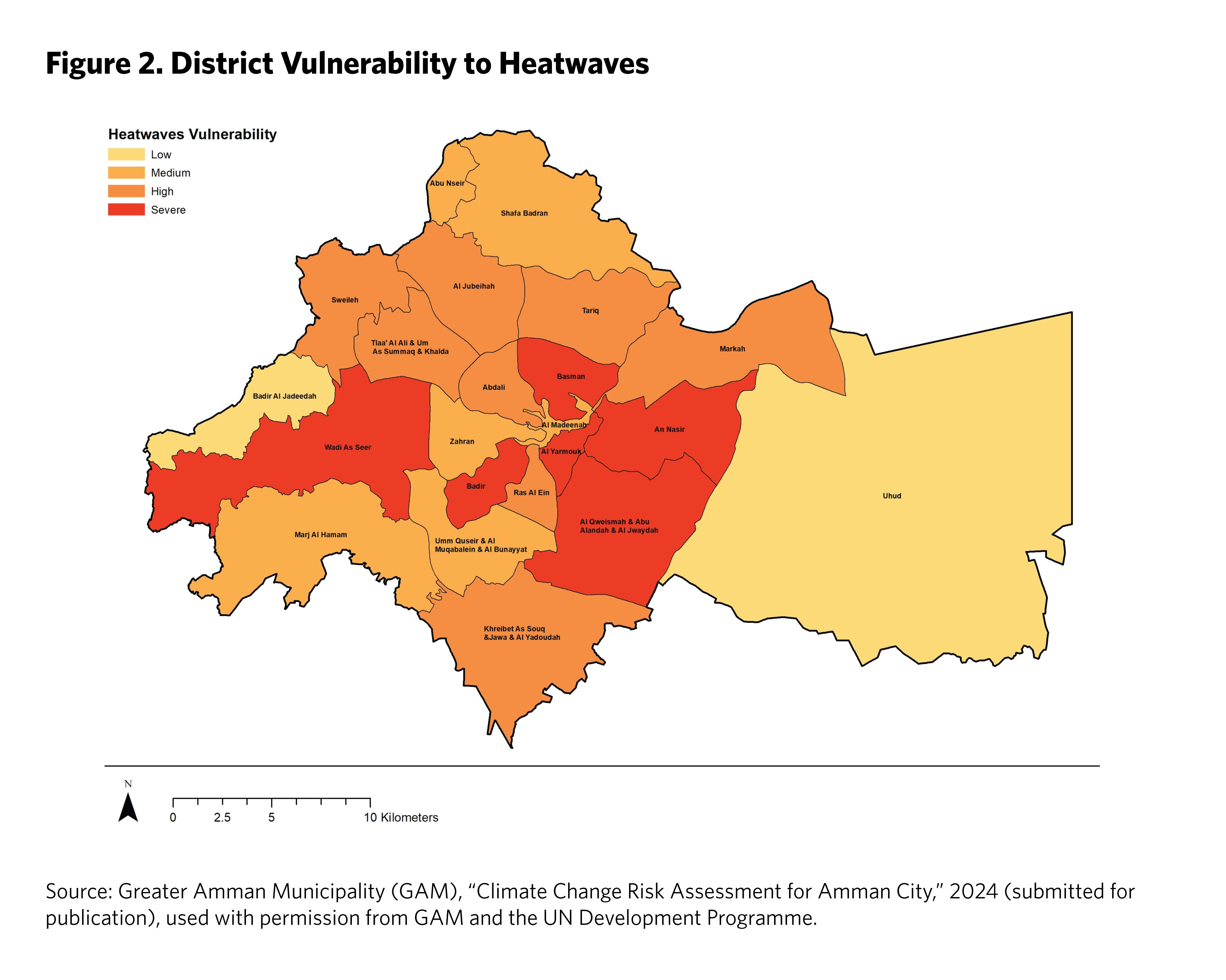

Heatwaves have emerged prominently as a significant hazard in Amman over the past decade. The city grapples with a pronounced heat island effect, amplified by high urbanization rates, limited green spaces, and escalating human activities like transportation and construction. Assessing the vulnerability of Amman’s districts to heatwaves involves analyzing exposure levels of people and assets, identifying sensitivity among specific groups and urban systems, and evaluating the adaptive capacity of these systems and sectors.

Factors such as population, population density, refugee populations, and household numbers serve as crucial benchmarks for gauging district exposure to heatwaves. Although all citizens face exposure, the focus of assessment remains on particularly vulnerable groups that are highly susceptible to heat-related stress and health issues—namely, women, people with disabilities, refugees, youth, older people, and city workers. Districts hosting refugee camps also demonstrate sensitivity to such extreme events because of the poor living conditions for refugees such as overcrowding, less economic opportunities, and health issues.

Heatwaves strain water and electricity consumption, leading to potential shortages or blackouts; exacerbating water stress; and impacting the availability of resources for people, animals, and vegetation. Districts with impaired water networks are notably sensitive to consequences arising from heatwaves. Rising temperatures can also affect vehicle efficiency and lead to malfunctions, particularly in built-up areas that significantly contribute to the heat island effect. These malfunctions render these districts even more sensitive to heatwaves.

Moreover, heatwaves intensify drought conditions, impacting undeveloped green areas and causing soil erosion. Assessing district vulnerability to heatwaves also encompasses evaluating public health aspects. Elevated temperatures correlate with increased insect reproduction, prompting the municipality’s digitized complaint system on insect and rodent control to shed light on spatial distribution and identify problem areas affecting public health.

Conversely, evaluating the vulnerability of city systems and services across multiple sectors involves considering the availability and coverage of green infrastructure, the adoption of renewable energy like solar systems, GAM emergency units’ readiness for emergency response to heatwaves, and the healthcare sector’s responsiveness. This evaluation includes the distribution of healthcare centers across districts and the number of citizens covered by health insurance, both public and private.

The vulnerability map in Figure 2 highlights central districts like Basman, Al Yarmouk, An Nasir, Badir, Al Qweismah, Abu Alanda, Al Jwaydah, and the western district of Wadi As Seer as severely vulnerable to heatwaves. In contrast, peripherally located districts like Uhud, with minimal population and fewer built-up areas, and Badir Al Jadeedeh, known for its conserved natural forests and planned green residential zones, exhibit comparatively lower vulnerability.

Amman’s District-Level Vulnerability to Drought

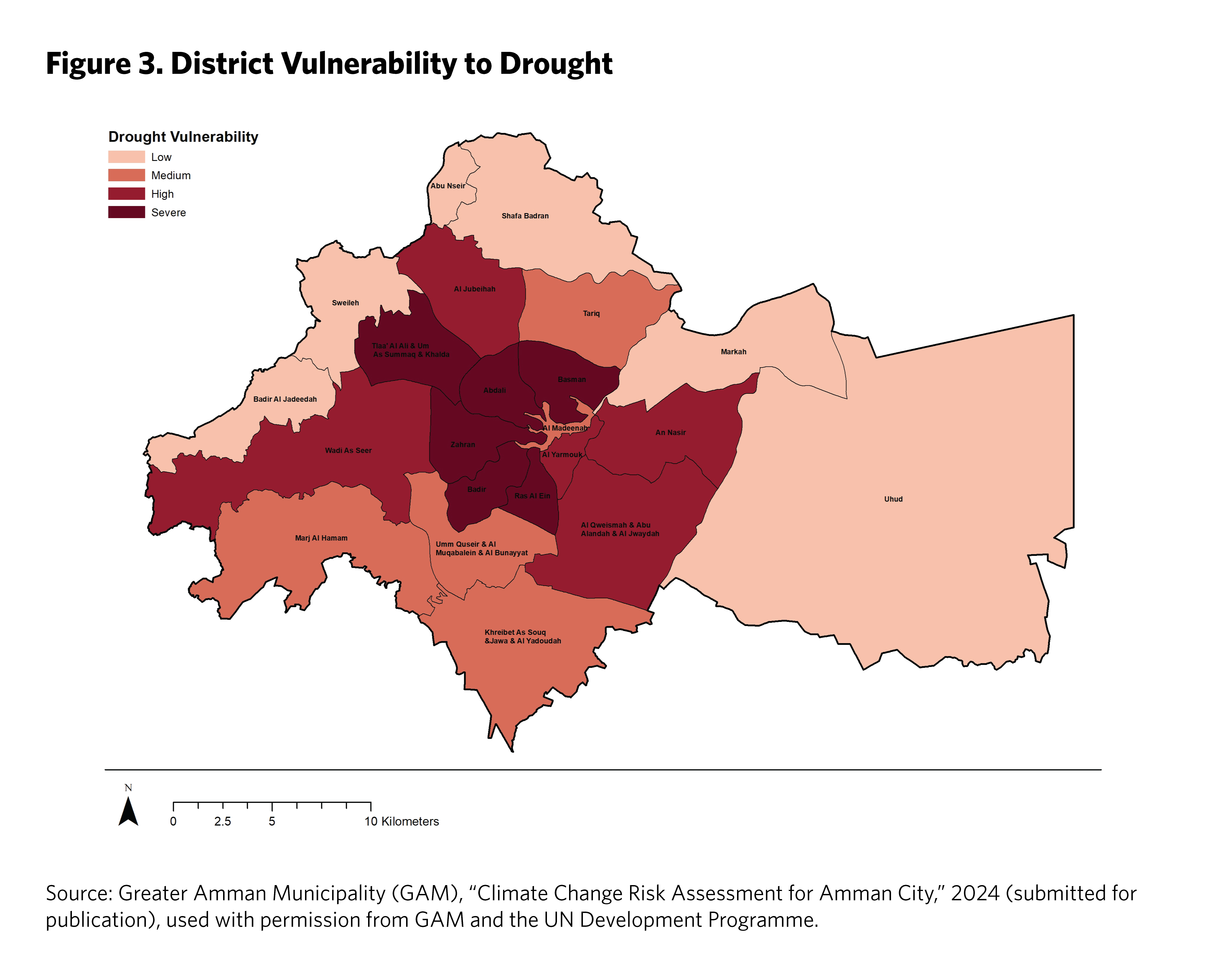

The impact of drought on water security in Amman is undisputable. The vulnerability assessment focuses on understanding each district’s exposure, sensitivity, and level of adaptation to drought. Factors such as population distribution, refugee density, and household numbers indicate the district’s exposure. Residential and commercial areas exhibit the highest sensitivity to water scarcity; industries and heritage sites also face considerable exposure. Public green spaces and trees are at risk owing to limited water availability and decreased precipitation. Moreover, the soil quality in undeveloped areas deteriorates with recurrent drought events.

Although the entire population is sensitive to drought, certain groups—women, people with disabilities, youth, older people, and city workers—are particularly vulnerable. During drought events, public water subscribers, especially in residential buildings, endure more frequent water supply restrictions, particularly in hot summers, escalating water consumption demands. Additionally, damaged water networks impede efforts to address nonrevenue water issues, exacerbating the situation.

The GAM has been actively implementing projects to manage water resources and bolster resilience against water scarcity exacerbated by urbanization. These initiatives encompass promoting water harvesting, investing in green infrastructure, and enhancing wastewater treatment technologies. The city has constructed underground water-harvesting tanks and wells for irrigation purposes.

Efforts by Miyahuna, the water company in Amman, include technical maintenance of pumping stations and public/private water and wastewater networks, fostering efficiency, water harvesting through reservoirs, and public awareness campaigns. Analyzing Amman’s systems, including the GAM, Miyahuna, and the Ministry of Health, aids in assessing the city’s coping capacities. Increased green space coverage and available vacant lands reduce the impact of drought by facilitating water infiltration during rainy seasons and replenishing groundwater wells in Amman. Furthermore, the availability and capacity of main water reservoirs, irrigation water storage, and livestock facilities play crucial roles.

Water scarcity has health implications for all citizens, especially vulnerable groups. The distribution of healthcare centers across the city and ensuring citizens are registered for health insurance contribute significantly to citizens’ adaptation to drought.

As seen in Figure 3, central districts like Basman, Abdali, Badir, Zahran, Ras Al Ein, Tlaa’ Al Ali, Um As Summaq, and Khalda are highly vulnerable to drought. Conversely, northern and western districts with abundant green spaces—such as Abu Nseir, Shafa Badran, Sweileh, and Badir Al Jadeedeh—are seen as less susceptible. Areas like Markah, which has groundwater wells, and Uhud, which has a lower population density, exhibit lower vulnerability to drought.

Amman’s District-Level Vulnerability to Flash Floods

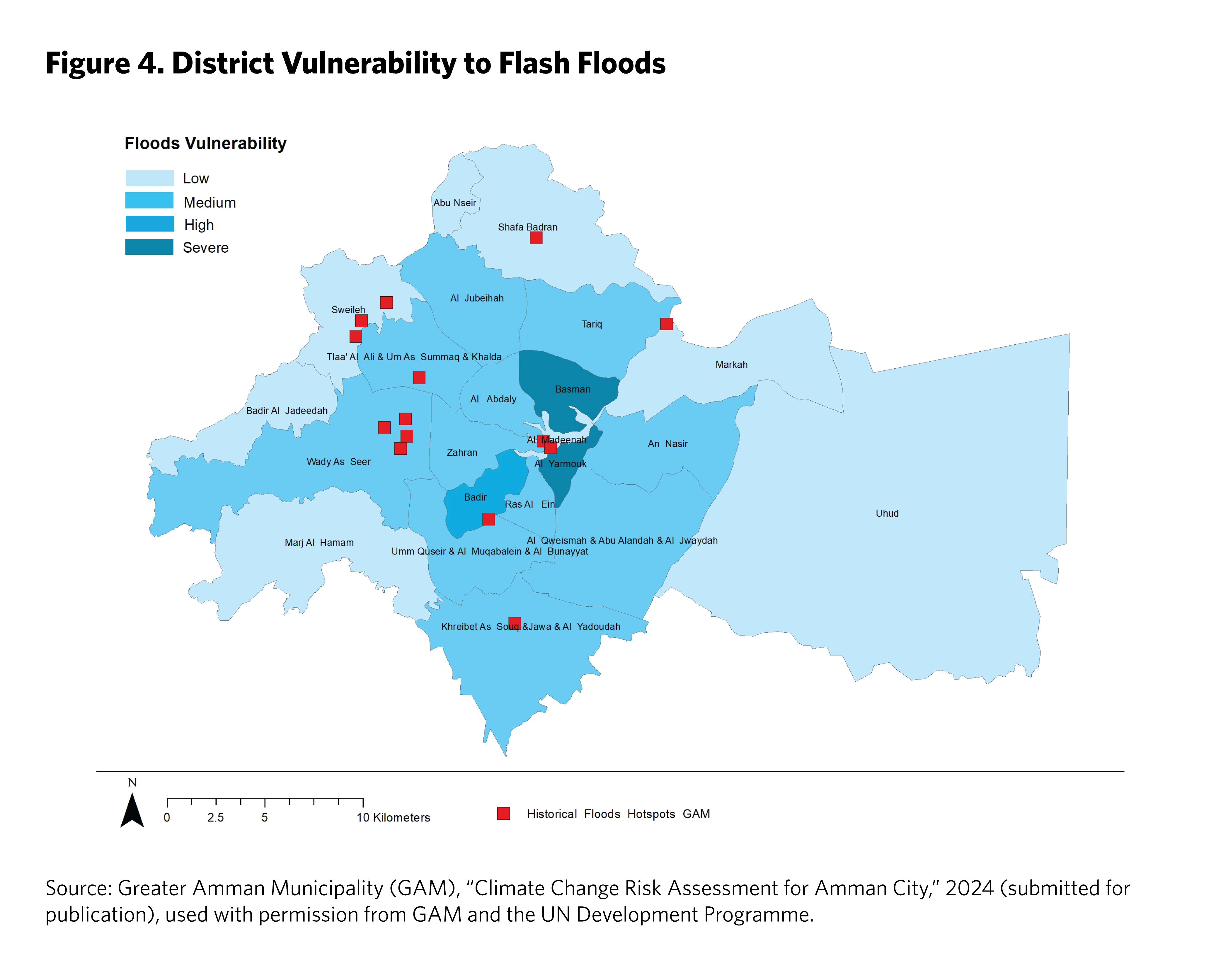

In recent times, Amman has faced increased flash flood occurrences. Initially, these issues were limited to lower-lying districts such as Al Madinah. However, this phenomenon has expanded to multiple districts, including Badir, Sweileh, Wady As Seer, Tlaa’ Al Ali, Um As Summaq, Khalda, Tariq, Shafa Badran, Khreibet As Souq, Jawa, and Al Yadoudah. In addition to topographical, hydrological, and land use characteristics of Amman’s districts, populated areas, including underprivileged refugee spaces, face greater exposure to flash floods. The presence of residential spaces, commercial hubs, and schools amplifies district vulnerability. Furthermore, heritage sites are highly susceptible to flood risks, especially in Al Madinah district.

Specific demographics—such as women, people with disabilities, youth, older people, and city workers—emerge as particularly sensitive populations during these events. Factors like concentrated refugee camps, tunnel infrastructure, and impermeable surfaces like asphalt contribute significantly to heightened vulnerability to flash floods. Conversely, green spaces and vacant lands are pivotal in augmenting districts’ adaptation capabilities.

Strategies such as stormwater drainage networks and using box culverts in tunnels have notably mitigated the impact of flash floods. The GAM has implemented emergency plans through its civil defense and emergency centers, effectively responding to these events, especially during the rainy seasons. The healthcare system’s availability and coverage through insurance play crucial roles in adapting to and managing the aftermath of floods.

Assessments reveal Basman and Al Yarmouk as severely vulnerable to floods (see figure 4). Marj Al Hamam, Al Madeenah, Abu Nseir, Shafa Badran, Sweileh, Badir Al Jadeedeh, Markah, and Uhud are least impacted by flash floods.

Amman’s District-Level Vulnerability to Vector-borne Diseases

Factors like high population density, refugee settlements with poor hygiene conditions, and various types of households contribute significantly to the spread of vector-borne diseases in urban areas. Residential, commercial, and industrial zones face heightened exposure. Owing to their vulnerable populations, services, and infrastructure, specific districts exhibit varying degrees of susceptibility to these diseases. Issues like damaged water systems, high waste generation, and prevailing public health concerns like insect infestation, rodent presence, and localized health risks compound the sensitivity of these areas to vector-borne illnesses.

Certain groups within the city, such as women, people with disabilities, youth, older people, and city workers, are sensitive to these diseases. Although the city has a robust pest control system, ensuring overall healthiness, the extent of sewage network coverage and the number of subscribers directly impact public health and disease prevalence. Public green spaces play a crucial role in moderating temperatures within districts, curbing the rampant proliferation of disease-carrying insects. Efficient and regular collection and safe disposal of municipal solid waste play a vital role in controlling the spread of these diseases. Additionally, well-situated health facilities and comprehensive health insurance coverage enhance the city’s adaptation to combat these health risks.

As a result of these factors, specific districts like Basman, Al Yarmouk, Al Qweismah, Abu Alanda, and Al Jwaydah are identified as highly vulnerable to vector-borne diseases (see figure 5). Conversely, areas like Shafa Badran and Badir Al Jadeedeh exhibit excellent adaptive capacities and are less vulnerable.

Amman’s District-Level Vulnerability to Airborne Diseases

Air pollution and climate change are extremely interconnected. The evolving concentration of fine particles, especially PM2.5—particulate matter with diameters that are less than or equal to 2.5 micrometers in size—causes air pollution, contributes to emergence of allergies and respiratory diseases, and aggravates the impact of noncommunicable diseases. In 2019, 3,074 people died in Jordan from causes attributable to fine particle pollution.

Figure 6 presents the airborne diseases vulnerability assessment in Amman City. It looks at the exposure of the general population and refugees, the density of the population, and the number of families in each district. In terms of human activities, districts with more residential, commercial, and industrial areas are highly expected to be exposed to airborne pathogens. People with disabilities, youth, older people, and city workers are more likely to be vulnerable to such diseases. Refugee camps with poor living conditions, such as overcrowding and inadequate ventilation, also make their residents vulnerable to such diseases.

Factors affecting the jurisdiction of Amman’s districts’ adaptation to airborne diseases are the green coverage represented by public green areas, electricity generation using renewable resources, and households using solar systems for water heating. All of these elements help reduce air pollution. Moreover, healthcare system availability and accessibility are both crucial in helping residents adapt to respiratory and air quality–affected diseases.

The Amman vulnerability map below shows that Basman, Al Yarmouk, Al Qweismah, Abu Alanda, and Al Jwaydah, followed by Badir and An Nasir, are most acutely vulnerable and highly impacted by airborne and respiratory diseases (see figure 6).

Climate Projections: Districts at Risk

The IPCC defines risk as “The potential for adverse consequences for human or ecological systems, recognising the diversity of values and objectives associated with such systems. In the context of climate change, risks can arise from potential impacts of climate change as well as human responses to climate change. Relevant adverse consequences include those on lives, livelihoods, health and well-being, economic, social and cultural assets and investments, infrastructure, services (including ecosystem services), ecosystems and species.”

By the end of the century, Jordan is projected to experience a warmer, drier, slightly humid climate. Rising air minimum and maximum temperatures for two GHG emissions pathways (Representative Concentration Pathways, or RCPs), RCPs 4.5 and 8.5, are most likely to increase by 1.2°C and 2.7°C, respectively, due to RCPs 4.5 and 8.5, respectively. As per the 4NC report, there is no evidence of future heavy rain days (more than 20 millimeters), yet projections show decreasing likelihood of intense precipitation, particularly under RCP 8.5 compared to RCP 4.5. However, the severity varies by location, leaning toward increased intensity by the middle of the twenty-first century and decreasing toward the century’s end. Further, the report reveals the future trend of drought with an increase in drought events, scale, and duration, with anomalies in severity across the country. Heatwaves are forecasted to happen more frequently and intense in magnitude and intervals of time.

The risk assessment considers the interplay between future climatic hazards and the vulnerability specific to each hazard. This assessment extends until 2100, utilizing scientific data from the 4NC report and focusing on two representative concentration pathways: RCP4.5 and RCP8.5.

By 2100, heatwave risks in Amman are expected to be notably high in Basman, Badir, Al Yarmouk, An Nasir, Al Qweismah, Abu Alanda, and Al Jwaydah for both RCP scenarios. Drought will significantly affect Abdali, Badir, Basman, Zahran, Ras Al Ein, Sweileh, Um Quseir, Al Muqabalein, and Al Bunayyat under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5. Regarding flash floods, discrepancies are observed between RCP4.5 and RCP8.5. Districts such as Tlaa’ Al Ali, Um As Summaq, Khalda, Basman, Al Yarmouk, Badir, Al Qweismah, Abu Alanda, and Al Jwaydah face elevated risk of flooding. In contrast, under RCP8.5, the most pronounced impacts are expected in Basman, Badir, Al Yarmouk, Um Quseir, Al Muqabalein, Al Bunayyat, Al Qweismah, Abu Alanda, and Al Jwaydah. Basman and Al Yarmouk are particularly susceptible to vector- and airborne diseases, while Badir, Al Qweismah, Abu Alanda, and Al Jwaydah also face risks related to airborne illnesses.

Conclusion

The city of Amman stands out as a pioneer in climate governance within the region, with ambitious climate action plans and strategies. Despite these strides, the journey of adapting to and addressing forthcoming climate risks, as well as curbing their impact, remains arduous. The city is lagging in the determined reduction of carbon dioxide emissions stated in its first Amman Action Plan, as the IPCC underscores the uncertainties surrounding climate actions, and cautions against potential risks arising from implementation, policy effectiveness, technological advancements, and system transitions.

For Amman, prioritizing climate resilience is imperative. It will be crucial for the city to align its adaptation plan with the national strategy. Embracing social infrastructure, nature-based solutions, and upgrades to critical physical infrastructure can bolster the city’s capacity to withstand climate-related hazards. The prolonged challenge of urbanization, inefficient land use and zoning planning, and the looming threat of exacerbated inequalities caused by uneven distribution of natural resources underscores the need for a paradigm shift in city development through integrated urban planning, ensuring a resilient, green, just, and inclusive city.

The cornerstone of effective mitigation and adaptation lies in disaggregated climate data. Amman’s Urban Observatory must devise inclusive, evidence-based environmental indicators aligned with climate plans and SDGs, all of which can emphasize district-level socioeconomic and health data for inclusivity and reduced inequalities among vulnerable groups. Coordinated efforts across multiple levels and stakeholders are essential. Consequently, it is vital for the city to establish an Early Warning System aligned with the national early warning system and develop local disaster risk reduction strategies.

Disaggregated climate data make up the cornerstone of effective and efficient mitigation and adaptation to climate resilience. Amman’s Urban Observatory must develop inclusive environmental and climate-hazard indicators. Indicators must be measurable, scientific, evidence-based, and up to date to be monitored in the short, medium, and long terms. Moreover, disaggregating socioeconomic and health data at the district level ensures inclusivity and reduces inequalities, creating an approach that better serves vulnerable groups exposed to multilateral climate crises. Finally, multilevel and multistakeholder coordination on data is a must.

As in many cities, financial resources are at the top of challenges. Amman requires innovative and sustainable climate action financing mechanisms and partnerships through public-private partnerships to implement the necessary projects. Local and national government efforts, citizen awareness, and behaviors encouraging more responsive consumption of resources will all be necessary for effective climate action in Amman.

This article is based on the findings and analysis from the Climate Change Risk Assessment for Amman City. That assessment was sponsored by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and produced for the Greater Amman Municipality. The author of this article was the lead expert on the assessment. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not represent those of the UNDP, UN-Habitat, UNEP, or Greater Amman Municipality. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data and analysis provided in this article, readers are advised to exercise discretion and consult additional sources for specific inquiries or decisions. The author and contributors disclaim any liability for errors, omissions, or interpretations arising from the use of this article.

[1] Greater Amman Municipality, “Climate Change Risk Assessment for Amman City,” 2024 (submitted for publication).

[2] Greater Amman Municipality, “Climate Change Risk Assessment for Amman City.”

[3] Greater Amman Municipality, 2023. Interview with the head of Amman Resilience Unit at GAM.

In this series on climate change, vulnerability, and governance, Carnegie scholars and contributors analyze how climate change impacts socioeconomically vulnerable populations and infrastructures and shapes governance systems and capacities in the MENA region.

For more in the series, see:

- Assessing Climate Adaptation Plans in the Middle East and North Africa

- The Looming Climate and Water Crisis in the Middle East and North Africa

- On the Margins: Civil Society Activism and Climate Change in Egypt

- Vulnerability and Governance in the Context of Climate Change in Jordan

- Just Energy Transitions? Lessons From Oman and Morocco

- Climate Vulnerability in Libya: Building Resilience Through Local Empowerment

- What Tunisia’s Municipalities Can Contribute to Climate Adaptation

- Climate Change in the Middle East and North Africa: Mitigating Vulnerabilities and Designing Effective Policies