Summary

For decades, the West has been unable to build an effective strategy on Belarus due to the country’s limited geopolitical importance, an inexorably deeper dependence on Moscow, and the glaring absence of leverage over Minsk’s strategic decisionmaking. This paper proposes a different paradigm for approaching the issue. Instead of passively reacting to Minsk’s actions, the West should broaden its planning horizon and create more specific incentives for Belarus to follow a different trajectory in the future.

The overriding goal of a more proactive Western strategy should be the eventual emergence of a democratic Belarus that is no longer fully dominated by Moscow in the military and political realms. Such an ambitious goal would have tangible and lasting benefits for the new European security landscape amid the prospect of a long war in Ukraine.

Skepticism in Western policy circles about the viability of such a scenario is entirely understandable. Yet it is not entirely clear whether Western policymakers have registered the significant differences between Russia and Belarus at the societal level and divergent strategic interests of the Russian and Belarusian regimes.

At the same time, it is essential for Western policymakers to keep their expectations in check and to avoid an overestimation of their capabilities. The Belarusian crisis cannot be resolved in the foreseeable future by Western efforts alone.

Moreover, there should be no illusions about the fact that Belarus, much like Ukraine, holds a special place in the worldview of the Russian ruling elite and President Vladimir Putin personally. The Kremlin’s long-standing obsession with keeping the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) away from Russia’s borders plays into the same attachment to keeping the Belarusian regime in as tight an embrace as possible. Therefore, until Moscow either changes its foreign policy priorities under a new leadership or simply becomes unable to keep Minsk under its control, it would be naïve to expect that the Russian leadership will simply offer any Belarusian government greater leeway to shift its geopolitical orientation.

At the same time, it is conceivable that a qualitative increase in military assistance to Ukraine and a more effective economic pressure campaign against Russia could disrupt Belarus’s trajectory and make Minsk more amenable to the incentives that the West can already offer. But an overnight breakthrough seems highly unlikely. This paper, therefore, focuses on more realistic recommendations with longer-term effects.

Policy Recommendations

First, the West should expand support to prodemocracy elements of Belarusian society, which showed their potential during the mass protests of 2020. To encourage the future political modernization of Belarus, a network of connections should be established between these people and the democratic world. That also means pushing back against efforts by the regimes in Minsk and Moscow to isolate these forces from the West. Such support includes expanding the infrastructure of Belarusian media in exile, which remains the only reliable independent source of information about Belarus.

Second, sanctions must be a flexible tool that can be either tightened to stop them from being circumvented or eased swiftly when the current or a subsequent government in Minsk is ready to make more serious concessions to restore relations with the West. To this end, it is worth drawing up a road map now outlining mutual steps to overcome the crisis in relations and conveying that vision to Minsk. An initial focal point could be sanctions whose lifting would contribute to bolstering the autonomy of the Belarusian economy and reducing Russia’s levers of influence.

Third, it is worth keeping channels of communication with Minsk open in the meantime, including via a Western diplomatic presence in Belarus. Experience has shown that periodic contacts used to solve practical problems (such as the release of political prisoners) do not, in and of themselves, automatically lead to the international legitimization of contested president Alexander Lukashenko’s regime. Nor should such contacts prevent the West from maintaining its tough position. At the same time, it is important for the Belarusian leadership to see that the path to the West is not closed forever. At critical moments, that pathway will likely look more appealing to Minsk than conceding more of its sovereignty to the Kremlin.

Fourth, the West should keep the pressure on Russia to withdraw its tactical nuclear weapons from Belarus and ensure that this topic is an integral part of the overall context of the future postwar security environment in Central and Eastern Europe. The withdrawal of tactical nuclear weapons will reduce the risks to the entire region and give Minsk more room to maneuver in its foreign policy.

Finally, to keep Belarus from being forgotten in the West, it would be useful to strengthen policy coordination with like-minded countries, including by appointing a special representative for Belarus in Brussels to coordinate overall Western policy with EU member states and Washington.

Introduction

During the past three decades, Western policies on Belarus have been largely reactive, born of the various challenges posed by the Belarusian regime during this period. The relative importance of Belarus in Western foreign policy has always depended on several factors, from the physical distance of the country in question from Eastern Europe to the rare occasions when Belarus has been in the headlines. This fluctuating level of interest has prevented the West from developing a coherent and sustainable strategy that is geared to the long term and prioritizes proactive measures that can help Western leaders get off the back foot.

While it is laudable that Western governments have frequently put humanitarian values such as respect for human rights front and center, the uncomfortable reality is that key players have frequently struggled to articulate clear and achievable policy goals. A heavily reactive approach that is devoid of taking the initiative or serious long-term planning can hardly be expected to be a success. Moreover, outside observers are often left with the impression that there is not much agreement inside the West on what a successful relationship with Belarus would actually look like.

That problem is exacerbated by two unavoidable limiting factors: Western countries have very little leverage over Minsk, and the Kremlin cares a great deal more about Belarus than Western governments do. Regrettably, there is little or no immediate prospect of that changing. If anything, Russia’s domination of its neighbor continues to increase.

This paper proposes several routes out of the current vicious circle. Western leaders’ apathy and lack of interest in Belarus risk creating a self-fulfilling prophecy that leaves Belarus trapped in Moscow’s smothering embrace more or less indefinitely. The analysis below focuses on identifying options for a more effective Western strategy that does not require a root and branch reassessment of other more pressing foreign policy priorities and that takes into account existing opportunities and limitations.

Overlooked Differences

Many Western politicians doubt whether Belarus still has enough scope for independent action. If not, they ask all too understandably, why bother to generate a separate strategy? Indeed, in terms of sanctions policy, for the last two years the EU and United States have generally lumped Minsk and Moscow together as two sides of the same coin. (Note: there have been occasional exceptions to this approach, namely the minor, targeted personal sanctions packages released on the anniversary of Belarus’s fraudulent presidential election in August 2020.)

Western perceptions of Belarus as having irredeemably thrown its lot in with Russia are entirely understandable. Putin appears to meet with his Belarusian counterpart Alexander Lukashenko more often than he sits down with other senior Russian officials. The Russian army makes free use of Belarusian territory and military infrastructure for its own needs. Since summer 2023, Russian tactical nuclear weapons—or at the very least, their components—have been deployed in Belarus.1 Two-thirds of Belarusian exports go to Russia, and a significant proportion of the remaining third is dependent on Russian logistics chains. Minsk has signed up to every post-Soviet political, security, and economic integration scheme developed by the Kremlin. Russia repays Minsk’s loyalty in the form of access to cheap energy, new loans, deferred repayment and refinancing of previous loans, and other forms of support.

At the same time, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that there is still a clear gap between the strategic interests of Minsk and Moscow. Sovereignty is a basic requirement for any authoritarian regime, and Belarus is no exception. For its part, the Russian leadership clearly sees Belarusian and Ukrainian sovereignty as historical accidents that now need to be corrected.

That suggests there is a significant gap between the interests of Minsk and Moscow that could be exploited, depending on the future course of regional developments and the economic situation in both countries. For example, if Moscow becomes less able or willing to maintain its current levels of financial support for Belarus, that could give rise to new tensions, just as it has on numerous occasions since Putin’s rise to power in 2000.

Overt and Informal Levers

Belarus and Russia are the most closely integrated countries in the post-Soviet space, including in military terms. There are no official Russian military bases in Belarus, but the country does host two Russian military sites which are home to approximately 1,500 troops in total. Up to 30,000 Russian troops were massed in Belarus ahead of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and crossed the border as part of the Russian military’s attempt to seize Kyiv. In addition, Russia has since then stationed tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus and maintains air defense and air force training facilities.

At the political level, however, the overwhelming majority of documents signed by the two governments over the last quarter-century are meaningless without the goodwill of both sides. Unfortunately, it has become a common shorthand in Western discourse to portray organizations that Moscow has created—like the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Collective Security Treaty Organization—as de facto military alliances or effective vehicles for granting Russia control over its neighbors. In reality, these groupings largely operate upon the principle of consensus and do not impose any nonnegotiable supranational obligations on their post-Soviet members. Similarly, decisionmaking by the Eurasian Economic Union is also made by consensus at the three most senior levels of the organization’s four levels of management.2

The high water mark of the two countries’ integration was supposed to be the Union State of Belarus and Russia. In reality, it is nowhere near the de facto confederation envisaged by the founding documents dating from 1999. Attempts in recent years to deepen this integration have not resulted in any kind of breakthrough. Instead of the ambitious road maps to integration put forward by Moscow in 2019, the most recent move by the two sides was to agree on twenty-eight “union programs” at the end of 2021. Those documents merely brought the two countries’ legislation in certain areas into closer alignment, without creating any supranational organs—with the exception of a “tax committee” planned to be created in 2024. Even that new oversight body will retain parity in decisionmaking between Belarus and Russia, with six votes each.3 This principle also applies in all the other bodies of the Union State, meaning Moscow lacks a formal means of dominating this integration structure.

In other words, Moscow has no official way of preventing Minsk from halting the work of any of these integration structures or suspending its participation in them. Up until now, Minsk has unfailingly sought to torpedo any attempts to create such mechanisms for Moscow in both bilateral and multilateral formats. This is another fundamental difference between the interests of the Belarusian and Russian regimes: the former strives to preserve its autonomy while the latter aspires to broaden the scope of its dominance.

Of course, Russia has other, largely informal forms of leverage that are likely far more serious when it comes to restraining any maneuvering by Minsk. Such tools will surely remain in place even after Lukashenko leaves power. That leverage stems primarily from the Belarusian economy’s dependence on Russia. The potential normalization of relations between Minsk and the West could replace some lost trade and logistics connections, and even some energy sources, but it would only soften the blow rather than resolving the problem entirely. Minsk would not be able to leave its shared trade and customs area with Russia without an enormous shock to its economy. It is difficult to imagine Belarus being able to put an alternative plan into place at short notice or over Russian objections.

It is important to emphasize, however, that the essential first step in developing Western strategy on Belarus is to avoid extremes when evaluating the relationship between Belarus and Russia. Minsk’s dependence on Moscow has deep roots, but many of the concessions made in the name of integration by Lukashenko during his thirty-year reign are reversible in the right circumstances, and some of those circumstances can be influenced by the West. Minsk’s autonomy in foreign policy has been weakened considerably, but it has not disappeared completely. Nor is it static, since if nothing else, such autonomy is a by-product of the fundamental differences between the two regimes’ political survival strategies. An altered context—such as a Russia that is badly hobbled by the ultimate outcome of the war in Ukraine—could further exacerbate such differences.

A Distinct Society

Another issue that currently distinguishes Belarus from Russia is the attitude of Belarusian society toward the war and to the country’s place in the region. This issue has the potential to become the driving factor in returning Minsk to a less pro-Russian path.

Since February 2022, extensive sociological research—both online panels4 and phone surveys5—has shown a solid anti-war consensus in Belarusian society. Throughout that time frame, the percentage of people who support the Belarusian army joining the war on Russia’s side has hovered between 3 and 10 percent.

At the same time, the picture that emerges from these data is somewhat complex. Russia’s position and goals in the war have the support of about 33–40 percent of Belarusians. Allowing the use of Belarusian territory to launch missiles into Ukraine, to stage the original invasion in February 2022, to house exiled Wagner Group mercenaries following Yevgeny Prigozhin’s failed mutiny in summer 2022,6 and to host Russian tactical nuclear weapons in summer 2023 all had the support of approximately 20–35 percent of respondents. A quarter of Belarusians would like to see Moscow win the war outright: twice as many as would like to see Ukraine win. The rest are in favor of an immediate ceasefire.7 In other words, despite intensive and militaristic Russian propaganda and the military alliance between Lukashenko and Putin, most Belarusians do not see the war in Ukraine as their war, and they wish to stay well out of it.

The majority of Belarusians, regardless of their political leanings, have long supported the existence of a sovereign Belarusian state. This is why support for the idea of Belarus and Russia merging into one state is constantly less than 10 percent among Belarusians.8In polls conducted before February 2022 about Minsk’s ideal foreign policy trajectory, roughly 60 percent of respondents expressed support for some form of neutrality or a policy based on equidistant relationships with major powers. It was only after the start of the full-scale war that this approach of being on good terms with everyone became unrealistic, which led, in turn, to a new trend of decreased support for neutrality. Instead, there was a jump in the level of support for the pro-Russian and pro-European “extremes.” Still, the relative majority—45–50 percent—continue to prefer some form of neutrality.

Like many other variables in public opinion, the public mood in Belarus is constantly evolving. On the one hand, growth in support for Russia has been facilitated by the emigration of hundreds of thousands of politically active Belarusians, restricted access to independent media, and the normalization of an extremely pro-Russian discourse in state media. On the other hand, war fatigue and the deadlock in the fighting makes Belarusians less susceptible to the pro-Russian content to which they are constantly exposed.

Which trends will prevail in the future is unclear. What is apparent, however, is that while harboring a significant degree of sympathy for Russian foreign policy narratives, the majority of Belarusians are clearly able to distinguish between their country’s own national interest and that of Russia.

The Value of a Different Belarus

The aforementioned differences in how the two regimes perceive their actual interests, the uneven—and perhaps even partly reversible—dependence of Minsk on Moscow, and the notable gap between the public mood in both countries should serve as dampeners on Western fatalism about Belarus’s eventual full absorption into Russia. There is a broad range of scenarios for the long-term future of Belarus that need to be considered by Western policymakers. They run the gamut from Belarus’s emergence as a militarized outpost of a revanchist, belligerent Russia to the possibility of Belarus’s becoming a stable, predictable, and perhaps even neutral state capable of cooperating with its neighbors and dismantling the legacy of a violent, pro-Russian authoritarian regime.

The latter scenario is obviously the most preferable possibility for Western democracies and for Ukraine. To the extent the Russian army is able to preserve untrammelled access to Belarusian territory and military infrastructure, the potential line of contact between Ukraine and its enemy would increase by 1,080 kilometers (about 670 miles). The events of February 2022 demonstrated the danger posed by a Russian military staging ground within close proximity of Kyiv. A Belarus released from its military alliance with Russia would reduce the risks to Ukraine and allow Kyiv to redistribute precious military resources more effectively to defend its borders elsewhere.

The same could be said of the Suwalki Gap, a potential chokepoint along the border between Poland and Lithuania that is about 100 kilometers (60 miles) wide and that separates Belarus from Russia’s exclave of Kaliningrad. A seizure of the Suwalki Gap by the Russian military would cut off overland access to the Baltic countries from neighboring NATO member Poland.9 While the geostrategic significance of the Suwalki Gap is debatable, this potential element of vulnerability would be reduced if Belarus were no longer under Russian military influence.

Then there are the potential long-term threats from Belarusian authoritarianism. The hostile foreign policy of such regimes often stems from the autocrat’s need to deflect public attention away from domestic problems onto a foreign enemy. Lack of legal accountability at home can make leaders throw caution to the wind in their dealings with neighboring countries.

Lukashenko has been a prime example of such behavior in recent years. In May 2021, he forced a Ryanair plane flying over Belarus to land in order to arrest a Belarusian activist, Roman Protasevich, who was on board. Lukashenko has also arranged for asylum-seekers from third countries to cross Belarus’s western border into neighboring Poland. This artificial migration crisis has flared intermittently for several years and has since been emulated by Russia to put pressure on Finland. The democratization (or at least modernization) of the Belarusian regime into a less despotic model would not completely preclude further conflict with its neighbors, but the extent of the risk posed by Belarus would clearly decrease.

Third, a Belarus that is hostile to the West stands in the way of a direct trade route from Ukraine to the Baltic Sea, which would be useful both for supplying Ukraine with fuel and for exporting the country’s goods, including grain. Under improved relations with Minsk, that route could pass through the territory of Belarus, which—unlike Poland and other countries—has the same size train tracks as Ukraine and the Baltic countries, facilitating the movement of goods. Even in late 2020, after the beginning of the political turmoil in Belarus, Kyiv and Vilnius discussed increasing freight rail communication between Ukrainian and Lithuanian ports through the territory of Belarus.10 Less than a year earlier, Minsk had experimented with purchasing oil from non-Russian suppliers such as the United States (via the Lithuanian port of Klaipeda) and via the Ukrainian port of Odesa (from Azerbaijan). In the latter case, the parties exploited the currently unused oil pipeline between Ukraine and Belarus, which could be put back into operation under the right political and economic conditions. The increased interconnectivity of the Baltic region, Ukraine, and Belarus can also be seen as a factor in their joint resilience to Russia’s efforts to dominate the region economically.

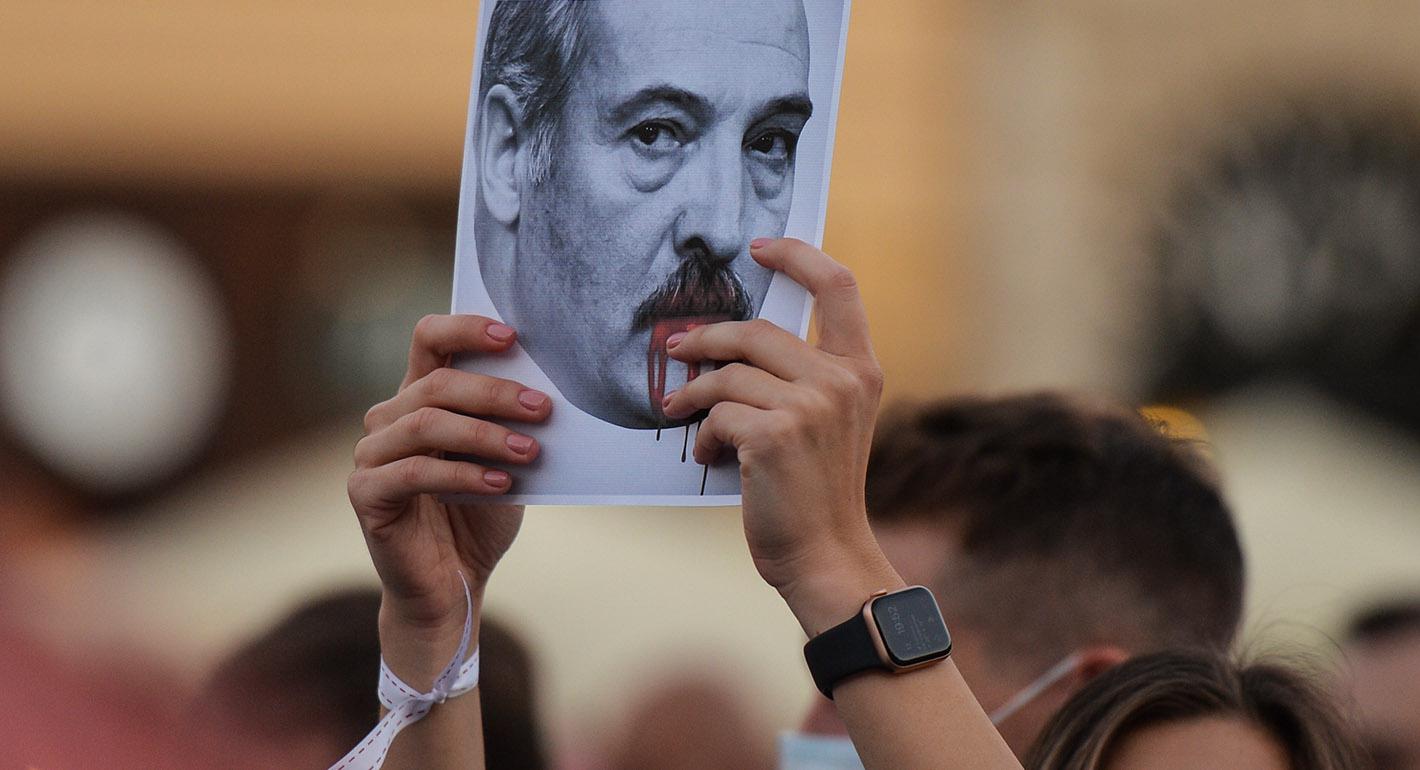

Finally, and less pragmatically, it matters how Belarusians’ brave efforts to stand up to tyranny, electoral fraud, and police violence following the rigged August 2020 presidential election are perceived in the long run. If it is remembered as a so-called Belarusian Tiananmen Square, that would have a dispiriting effect on prodemocracy movements elsewhere in the world. They would learn another demotivating lesson: that brute force used by an autocracy with the support of a more powerful geopolitical actor works even on the European continent, and the West can do very little about it. On the other hand, uninterrupted support for the democratic cause in Belarus that one day results in the country’s political emancipation from Russia’s autocratic grip would produce an opposite, inspirational example for others.

For all of these reasons, the West needs a proactive strategy on Belarus, one that is distinct from Russia policy. Those who advocate for a unified Western policy on Moscow and Minsk ignore all the differences between their societies and interests outlined above, as well as the potential for Belarus to one day become autonomous. The lack of a separate strategy on Belarus diminishes the chance of positive changes in Belarus or, at the very least, delays that prospect. Ideally, the goal of such a strategy should be the independent democratization of Belarus and its emergence from Russian military and political domination. Any movement toward that goal should be seen as progress worthy of investing Western efforts and resources.

Realistic Expectations

The heavy dependency of Minsk on Moscow obviously decreases the potential for any direct Western influence on the Belarusian regime. The effectiveness of Western pressure directly depends on Russia’s readiness to compensate Belarus for damages inflicted by sanctions. Although previous sanctions were far less punitive than the current measures, it was their impact that prompted Minsk to temporarily normalize relations with the West back in 2008 and 2015: Lukashenko did not feel he was receiving adequate support from Russia. Accordingly, it was no problem for him to make the main concession asked of him and release political prisoners.

Today the situation is fundamentally different. First, the concessions expected of Lukashenko would be far greater than in the past. Second, much of the country’s trade and logistics has been reoriented toward Russia, meaning that Lukashenko is confident in facing down even the harshest Western sanctions. Third, Moscow’s readiness to prop up Minsk financially has only grown since the war, with Putin and Lukashenko closer than ever.

It is hard to hope in this situation that the West has any realistic chance of increasing its influence over Belarus to the point of altering the basic incentives driving Minsk’s behavior, which right now come from Russia. Yet it would be wrong to conclude that since the problem of Belarus cannot be directly solved right now, it can be forgotten until the geopolitical context changes. Belarus is not part of Russia: it has the potential to distance itself from Moscow in the future.

For Western governments, though, it would be helpful to accept that expectations may have to be tempered to make goals realistic, as well as to develop a longer-term view of the situation. Even the end of Putin’s and Lukashenko’s rule will not automatically mean the immediate democratization of Belarus or the restoration of its capacity for a more friendly or neutral foreign policy. Finding ways to punish Lukashenko’s regime for all its unlawful and disruptive actions remains important in the here and now. But it is also crucial for the West to be able to focus on creating the conditions needed to ensure that any window of opportunity in the future will be used to bring Belarus closer to a model of a state that is democratic, predictable to its neighbors, and more autonomous from Russia.

Such windows of opportunity could open either as a result of largely unpredictable events such as the war in Ukraine or as a consequence of Putin’s and Lukashenko’s advancing ages (resulting in political succession in either country). Any of these factors could cause a political earthquake in Russia, Belarus, or even in both countries simultaneously, and the West risks not being prepared for that eventuality. Consequently, one of the West’s tasks should be to waste no time in creating incentives that will increase the chances of Minsk moving in the right direction in the event of a politically volatile situation.

Solutions for an Ideal World

That is not to say, of course, that Western countries should abandon attempts to influence Minsk in the present moment. The West certainly does not simply need to wait for the right moment: it has the power to hasten the time when Belarus will be more responsive to the carrots and sticks at Western countries’ disposal.

The most effective move in this respect is steadfast military and economic aid for Ukraine. This aid should be aimed at bringing about Russia’s military defeat, inflicting such losses that the Kremlin is forced to end its war. At the very least, the West must convince the Russian leadership that the idea that time is on its side in any war of attrition against Ukraine and the West is wrong-headed.

In such a scenario, a Russian realization that it simply cannot win the war and therefore must change tack, or an actual end to the war that results in Russia’s strategic weakening, would be the best grounds upon which to subsequently—or in parallel—resolve the problem of Belarus. It is important to remember that Lukashenko is very sensitive to any potential worsening of his own position. If the fighting in Ukraine or, more broadly, the standoff between Russia and the West appears to be heading toward a Russian defeat, Minsk will begin to hedge its bets in an attempt at damage control. In practical terms, judging by the last fifteen years, that means Minsk will be more prepared to distance itself from Russia and to make concessions at home. That will be the start of the required progress.

Second, the West should keep looking for ways to minimize the resources at Russia’s disposal—including the funds available to the Kremlin for supporting Lukashenko. To be sure, reducing inflow to Russian state coffers is no easy feat. At the same time, it is true that if the Kremlin is forced to tighten its purse strings and to reappraise the cost of open-ended expenditures like subsidies for Belarus, one should expect the seeds of conflict to grow between the Belarusian and Russian regimes. Any meaningful decrease in the volume of support is likely to provide an incentive for Minsk to make some changes.

As of this writing, however, it had become obvious that both components of this Western strategy of supporting Ukraine and inflicting economic damage against Russia had run into major obstacles. With U.S. military and economic assistance stalled in Congress and Putin awaiting the results of the U.S. presidential election, the Kremlin is increasingly confident about outlasting its adversaries. If the West is struggling to pass new aid packages in support of Kyiv and new sanctions against Moscow even despite the global risks a possible Russian victory in the war would entail, then the Belarusian factor clearly will not be able to move the situation forward. As a result, the recommendations that follow are less ambitious than the most potentially effective, but extremely difficult, solutions described above.

The Engine of Democracy

Only demand for democracy among Belarusians themselves can drive the country’s future political modernization. The mass protests following the rigged 2020 presidential election demonstrated not only how many Belarusians are in favor of democracy but also the broad sections of society they represent. Protests swept both small towns and major cities in all regions of the country, attracting a wide array of professional and demographic groups. Much of the protest movement was led by women.

At the same time, of course, Belarusian society is not homogenous. Lukashenko and the values he embodies also have their own support base, and the relationship between these two societal groups is constantly changing. Repression, the emigration of hundreds of thousands of politically active Belarusians, the ideological indoctrination and militarization of education, the blocking and closing down of independent media, and more aggressive pro-Russian propaganda have all taken their toll on the potential of the prodemocracy camp. Western countries should make efforts to counteract this trend, or at the very least, make it more difficult for the regimes in Minsk and Moscow to isolate Belarusian society from the democratic world.

A top priority, therefore, should be stronger support for Belarusian independent media, in the broadest sense of the word. As of this writing, the main social media sites and platforms remain unblocked in Belarus. Belarusian independent media have been agile in finding technical ways to minimize the effects of government attempts to block them. Taken together, these tools remain the most important source of free information for Belarusians, while the risks for individuals of accessing them is, in theory at least, relatively manageable. Opinion polling shows a correlation between key indicators of public opinion—ranging from views on the war, Russia, and the West to attitudes toward Lukashenko and democratic values—based on which types of media respondents consume.11

Unfortunately, there are indications that in the last two years, the size of the Belarusian audience for independent media based abroad has been gradually declining.12 One explanation is that people are afraid of being punished for even simply having a subscription to what the state deems “extremist” information sources (a term that covers nearly all nonstate media). Another is the growing overall depoliticization of Belarusian society. At the same time, however, whenever there is a major event, such as the start of the full-scale war, the announcement of a partial mobilization in Russia, or Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mutiny, overseas media outlets report a spike in their readership.13 At such moments, even the least politically minded Belarusians and those most fearful of repression seek out access to uncensored information about issues that are important to them.

On this basis, support for media should be seen as a long-term investment in supporting the infrastructure necessary for eventual political change in Belarus. At crucial moments in history, the political leanings and degree of engagement (or passivity) of Belarusians will depend on whether or not they have access to alternative sources of information. For this reason, it is essential for independent media to have the resources necessary to survive the current period of depoliticization and repression within the country.

Another priority should be to facilitate the movement of Belarusians who seek to travel abroad. Following the start of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, some European countries (Czech Republic, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia) restricted the issuance of residence permits and tourist and educational visas to Belarusians. (Restrictions for Russian nationals in those countries are either similar to those for Belarusians or even more stringent.) The practice of several other European countries also changed: instead of long-term multiple-entry visas, Belarusians began to receive single-entry visas much more frequently.

Such policies need to be reevaluated. Indeed, it is counterproductive for Western governments to create artificial barriers beyond those that are essential for national security purposes. The issuing of visas for the purposes of tourism and education should be encouraged and expanded, rather than the process becoming ever more complicated.

This also applies on a physical level. Dozens of tourist buses continue to operate daily between Belarus and its western neighbors. They often spend hours waiting in traffic due to the lack of operational border crossings. Passenger trains to Vilnius and Warsaw stopped running at the start of the pandemic in 2020 and should be reinstated.

Often these impediments to free movement are the result of actions by Minsk. It was the Belarusian government that systematically reduced the number of Western consulates operating in Belarus (and thereby their ability to issue visas). Minsk also deliberately created a migration crisis at EU borders, prompting Belarus’s western neighbors to tighten their border controls. Still, some Western countries have decided to issue fewer tourist visas to Belarusians since the start of the war or to limit them to single-entry rather than multi-entry visas, citing security interests. The same logic is often cited by Central European diplomats in response to proposals to restore the train connections.

These decisions do not appear to have been properly thought through. The main reason for the travel restrictions on Belarusians is the risks associated with the potential recruitment of these individuals by Belarusian special services, as well as possible infiltration of EU territory by Belarusian intelligence operatives. However, given the existence of multiple other ways to get into the EU and, therefore, into these frontline Eastern European countries, such barriers will not be impassable for malign actors. But the more impenetrable the border is for ordinary Belarusians, the weaker their ties will be to the West, as well as to their friends and relatives forced to flee repression in Belarus.

Before 2020, Belarusians were traditionally granted the most Schengen Area visas in the world per capita.14The desire of European politicians to protect their societies from risks posed by a neighboring state that is supporting Russian aggression against Ukraine is completely understandable. Frontline EU states are democracies that cannot ignore the demand of their voters to establish barriers, including against the flow of people from hostile countries. However, it is important to bear in mind the negative consequences of such steps for pursuing long-term Western objectives in the case of Belarus. The West should see that it is in its own interests to preserve the mobility of Belarusian society and to develop its links to Europe, including through education and business. Trapping Belarusians inside their country and reorienting their travel to the east can only weaken pro-European sentiment in the medium term. The main beneficiaries of such a trend will be the Belarusian and Russian authorities.

Sanctions Must Be More Flexible

Sanctions are the most significant tool that the West has for exercising direct influence over Belarus. Discussions over their efficacy usually begin (and sometimes end) with defining what constitutes effectiveness and how it can be measured. After all, to some extent, the effect is a matter of speculation: how different would Lukashenko’s behavior have been in the absence of Western sanctions? Would he have embarked on an even more destructive path if he had been convinced that his hold on power is truly invincible? Or would he in fact have been more cooperative if he did not feel a need to respond to Western escalation?

The generally accepted goal of sanctions against Belarus is to force Minsk to change its behavior by inflicting economic losses on it. Following the onset of mass repressions in 2020, dozens of Belarusian officials and companies close to Lukashenko were added to the blacklists of Western countries. After the forced landing of a Ryanair flight, the EU in June 2021 introduced the first sectoral sanctions (on tobacco products) and, along with other Western countries, severed aviation links with Belarus.

The sanctions lists were further expanded after the outbreak of the artificial migration crisis in October–November 2021, including against several key petrochemical enterprises. The sanctions imposed by the United States against Belaruskali—a top global producer of potash fertilizers—by early 2022 had led to the closure of the main transit route for this crucial Belarusian export commodity through the Lithuanian port of Klaipeda.

The most extensive sanctions were adopted by the West after February 24, 2022, due to Minsk’s complicity in the war. The most profitable Belarusian industries—including fertilizers, oil refining, wood products, and metallurgy—were subjected to sectoral sanctions. Four major banks were disconnected from SWIFT, a payment messaging system from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication. Western countries also introduced numerous export restrictions on electronics, dual-use goods, and other components that can be used by the defense industry, aimed at preventing the circumvention of anti-Russian sanctions. Throughout this period, the lists of personal sanctions against Belarusian officials, propagandists, businessmen close to Lukashenko, and members of his family, as well as against individual state companies from various economic sectors, were expanded.

An additional set of economic restrictions imposed on Belarus are intended to close loopholes in the sanctions against Russia and should be viewed as a separate issue. Those measures include an export ban on weapons, semiconductor chips with defense applications, and dual-use technology, as well as an embargo on Belarusian oil products. Easing those sanctions against Belarus would contradict the more important task of weakening Russia and limiting the resources at its disposal for waging war. The stronger Moscow is as a result of circumventing sanctions via Belarus, the less incentive there is for Minsk to change its policy. In addition, the Belarusian and Russian regimes would only grow closer still while cooperating over gray imports and exports via Belarus.

Still, aside from the anti-Russian measures that also affect Belarus, most of the sanctions target Minsk specifically, and in an ideal world, they should already be starting to nudge the Belarusian regime in the desired direction. But that is not happening.

Advocates of taking a tough line, including many Belarusian opposition politicians, say this is because there is insufficient pressure on the regime. They believe that if all possible sanctions are introduced against Belarus, Lukashenko will become more tractable. Yet the fewer measures left in Western arsenals, the less convincing that argument is becoming: if the most severe sanctions failed to have a positive impact on Lukashenko’s behavior, there is little reason to believe that exhausting the West’s remaining sanctions tools will lead to qualitative change.

Of course, a more expansive sanctions package could establish, in effect, a full economic blockade of Belarus by the West. Such efforts might include the closure of all cross-border trade with the EU, the removal of all Belarusian banks and corporations from SWIFT, and the freezing of Belarusian central bank reserves and correspondent accounts in the United States and EU. However, even such an effort would not necessarily create existential problems for Lukashenko. Indeed, if anything, Lukashenko senses that the West exhausted its most potent sanctions in 2022, yet the Belarusian economy is still standing.

After a record decline of 4.7 percent in 2022, GDP grew by 3.9 percent in 2023.15 Russia predictably became one of the key sources of this recovery. Russia continues to directly support the Belarusian economy through loan deferrals, cheap energy, and discounts on the use of Russian logistical infrastructure. It has also stimulated Belarusian industrial output through higher demand from Russia’s rapidly expanding military-industrial complex. As long as Russia is willing and able to support the Lukashenko regime, there is no reason to think that a more aggressive Western sanctions effort will force Lukashenko to make concessions.

For this reason, the West should return the focus of its sanctions policy to its main task: changing Minsk’s behavior. That means looking for incentives for Lukashenko—or whoever succeeds him—to take serious steps toward getting those sanctions lifted. Under this approach, sanctions should be a policy tool rather than a goal in themselves. For that tool to be most effective, it cannot become a permanent part of the political landscape or an established, new normal. Such an approach is bound to be counterproductive over the medium to long term, since the Lukashenko regime and its supporters in Russia will simply adapt to new circumstances and drain the sanctions program of its desired impact.

A more effective approach would entail the ability to ease or tighten sanctions, depending on circumstances. If existing sanctions are easily circumvented, Minsk will be considerably less keen to get them lifted. Accordingly, the West should continue to work on closing all the loopholes in both personal and sectoral sanctions. That means:

- toughening criminal and financial liability for residents of Western states who breach sanctions,

- investing more in exposing schemes to bypass sanctions (including investigations by media and nongovernmental organizations, as well as by Western governments),

- regularly updating sanctions lists to include intermediary firms and phony owners of companies that have previously been sanctioned, and

- instituting a more sustained and active program of secondary sanctions against companies in third countries helping to circumvent existing restrictions. This requires a sanctions mechanism in the EU that is more in line with the flexible and robust U.S. model, with its established practice of going after such facilitators of sanctions evasion. In the absence of a more effective EU sanctions mechanism, nonsectoral restrictions against Belarusian companies will likely only remain effective so long as their owners have failed to find intermediaries in other countries or to register their own shell companies.

On the other hand, the proposed approach also envisages more flexibility in the lifting of sanctions as and when needed to achieve political goals. Clearly, that day has not yet come. Lukashenko does not need to repair relations with the West so badly that he is prepared to make serious concessions.

Aside from helping Ukraine and putting more serious pressure on Russia, the West does not have any other ways of bringing that day forward. The lifting of sanctions should therefore be seen as a trump card in future negotiations with the Belarusian authorities that might only come many years down the line. In the meantime, the West can prepare the ground to ensure the optimal conditions.

A sensible starting point would be to identify a green list of current sanctions that could in theory be lifted in exchange for concessions made by Minsk, including before the end of the war in Ukraine and even without any improvement in relations between Russia and the West. This list should not contain measures whose lifting would enable Russian businesses to use Belarus to circumvent its own sanctions regime; instead, it should prioritize sectors of the Belarusian economy that do not primarily use Russian raw materials and that were least dependent on Russia before the introduction of sanctions. Obvious candidates for the list are aviation (first and foremost, the state carrier Belavia and westward flight routes), potash fertilizer, timber processing, and enterprises that have no connections to the Russian or Belarusian military-industrial complex.

The logic is simple: giving companies from these sectors access to Western markets will facilitate the process of the Belarusian economy becoming autonomous from the Russian economy. The same cannot be said of industries like oil refining or nitrogen fertilizers, which are entirely dependent on Russian raw materials.

The green list could also include personal sanctions against people close to Lukashenko—including both members of his family and businesspeople—who are not directly implicated in assisting the Russian army or taking part in domestic repression.

After identifying a list of sanctions that can be put on the table first, a road map should be drawn up of the precise concessions expected of Minsk in exchange for the step-by-step lifting of green list restrictions. These should include the release of political prisoners, an end to the artificially created migrant crisis, and maximum distancing—as far as feasible—from Russia’s war against Ukraine. Certainly, a halt in domestic repression would require the Lukashenko regime to roll back the now immense corpus of extremism legislation and to end continuing waves of politically driven arrests, routine physical violence against dissidents, and purges of opposition-minded professionals from various sectors of the economy, as well as allowing independent media and nongovernmental organizations to return and work in the country again.16This road map would then be shared with the Belarusian authorities.

On its own, the road map is unlikely to have an immediate impact on Minsk’s motivation to fulfill its own part of the future deal. But when external circumstances for the current or subsequent Belarusian authorities worsen, the existence of such a road map could accelerate the de-escalation process and have a positive effect on Minsk’s decisionmaking. Completing this preparatory stage now would also mean that whenever Minsk does become more amenable to negotiation, Western states will not have to waste long months deciding how to behave in the altered situation.

Having a roadmap will also increase the likelihood of Minsk viewing the normalization of relations with the West as an available option. If, at a critical juncture in relations with Moscow, Minsk believes Western doors to be closed for good, that will only hasten the erosion of Belarusian sovereignty—and the only winner from that scenario is the Kremlin. Accordingly, Lukashenko and other representatives of the nomenklatura should be given regular signals that there is an alternative path to relations with the West and that it is within Minsk’s power to travel down that path at any moment.

At the moment, it seems highly improbable that the West and Minsk will be able to complete this path to restoring relations under Lukashenko. However, given the right external conditions, some milestones along the road map—like the release of (some) political prisoners or ending the migrant crisis— could be implemented before any power transition in Belarus, as they do not undermine the viability of the Lukashenko regime.

Keeping the Door Open

For the same reasons, some form of limited contact and dialogue with the Lukashenko regime should be maintained. The preponderance of this effort can be handled via the presence of Western diplomatic missions in the country. It would be self-defeating to treat all forms of dialogue as a reward for bad behavior. Moreover, the existence of suchchannels would avoid wasting time in the future if there is an opportunity for a more productive relationship that merits restoration of higher-level dialogue—either under Lukashenko or someone else.

Diplomats are also an important source of information for the West, about what is happening in Belarus, identifying influential players within the existing regime, and monitoring socioeconomic conditions and living standards. None of these efforts should come at the expense of extensive contacts with opposition diaspora groups, but even with the best of intentions, politicians in exile may form misleading or overly optimistic assessments of the situation back home.

Both types of dialogue are useful for assembling an accurate composite picture that can enhance the effectiveness of Western policy steps. For example, if additional means of putting pressure on Minsk are warranted, it will remain essential to have the most realistic sense of the state of society and the potential fragility of the regime. Effective policymaking cannot occur in a vacuum.

When Lukashenko eventually leaves the scene, it is very likely that he will be succeeded by someone else from within the current nomenklatura, whose views and personal qualities are currently poorly understood in Western capitals. The question for Western players is whether it will be possible to establish and maintain lines of communication with these people. The potential benefits are straightforward enough: better channels for communication and mutual understanding could help reduce the likelihood of dangerous scenarios playing out during an eventual transition of power in Minsk—whether spontaneous or planned. The tricky part, of course, is how to handle members of the regime who have been directly involved in repressive activity and who might exploit any such interaction as a tool to denigrate Western players or sow disappointment in exile political circles.

Finally, Lukashenko has repeatedly shown that he is prepared to make certain compromises in exchange for symbolic recognition of his enduring power and importance. Following phone calls from then U.S. secretary of state Mike Pompeo in October 2020 and Israeli President Isaac Herzog in December 2021, nationals of those countries were released from Belarusian jails. Two phone calls from then German chancellor Angela Merkel at the height of the migrant crisis in November 2021, along with the tough positions of Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia, helped prompt Minsk to de-escalate the situation on the border.

Of course, not all problems in relations with the West can be solved this way. Lukashenko is unlikely to release political prisoners en masse purely in exchange for face time with senior Western officials. But if there is even the possibility it would help, then from a moral standpoint alone, such attempts should be made. Experience has shown that such contacts with Lukashenko do not lead to a significant improvement in his position on international affairs. They do, however, carry the possibility of positive steps involving individual cases of people in detention.

A Return to a Non-Nuclear Belarus

If and when Minsk wants to return to a more neutral policy in the future, a major challenge for any government—even post-Lukashenko—will be the removal of Russian tactical nuclear weapons that have apparently been deployed in Belarus since summer 2023. The West can and should help Minsk accomplish this task even if Moscow surely will have the last word. Restoring Belarus’s non-nuclear status would be in the interest of the West and Ukraine. But it also supported by a majority of Belarusians, who are opposed to having foreign tactical nuclear weapons on their soil, according to polling data.17

At the same time, it will be very difficult to separate the continued deployment of Russian tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus from whatever new security environment emerges at the end of the war in Ukraine. Moscow moved tactical nuclear weapons to Belarus as a signal that it was prepared for nuclear escalation against NATO over the war in Ukraine. Accordingly, the withdrawal of those weapons should be seen as a non-negotiable component of overall de-escalation and the transition to a new security configuration in the region following the end of the Russia-Ukraine war.

It is hard to predict, of course, whether Europe’s postwar security architecture will involve any form of talks and compromise with Russia. Given the belligerence of the Putin regime, it seems unlikely that the Kremlin will be in a mood to make good faith gestures any time soon. Nor are there any guarantees that the West and Ukraine will have sufficient leverage to trigger a Russian decision to withdraw its military presence and tactical nuclear weapons from Belarus.

To increase the chances of that particular issue being included in future talks, the West should already be articulating this demand regularly to both Russia and the Belarusian regime. Ideally, those demands should include the withdrawal from Belarus of all Russian troops and weapons systems deployed there in the run-up to and during the full-scale war against Ukraine, from the second half of 2021. Voicing this Western stance now can hardly be expected to affect the position of the current belligerent Russian leadership. However, consistently keeping this issue on the agenda for years before future talks on a new regional security configuration will increase the chances that this seemingly minor issue is not forgotten, and perhaps somewhere down the road ultimately resolved.

One of the biggest challenges facing Western efforts to remove Russian tactical nuclear weapons from Belarus derives from the fact that this decision was not initiated by Minsk. The official counterclaims from Minsk and Moscow that the Russian nuclear deployment in Belarus is simply a legitimate mirroring of NATO’s nuclear sharing policy do not hold much water. European allies of the United States (such as Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Türkiye) who agreed to host American nuclear warheads were exercising their sovereign will as democratically elected governments.

Lukashenko, however, was not recognized by the West as Belarus’s legitimate president in the wake of massive electoral fraud in the summer of 2020. That election was held months before Lukashenko made changes to the Belarusian constitution that formally ended its nuclear-free zone status. It was not until 2023 that Lukashenko signed an agreement with Russia on hosting nuclear weapons. Combined with the fact that most Belarusians were against the decision, that makes it hard to argue (as Lukashenko does) that hosting Russian nukes was a voluntary, sovereign decision by Belarus.

Institutionalizing Belarus

It is hardly new news that Belarus occupies a relatively low position in the foreign policy priorities of Western governments and bureaucracies. As a result, most Western governments are unlikely to dedicate much time or effort to assign senior-level figures to explore a new path, especially given the existing policy framework of lumping the Putin and Lukashenko regimes together. At the same time, the regular rotation of lower-level officials and diplomats in the West means that there is a frequent loss of institutional memory with regard to Belarus. Taken together, these dynamics only shorten the planning horizon and stack the deck in favor of continuing existing policies, even if they have yet to produce many desired outcomes.

To mitigate the consequences of this problem, Western governments should create posts for special representatives/envoys on Belarus, both within their own bureaucracies and at the international level. Some countries—France, Sweden, Poland, Lithuania, and Estonia—have already gone down this route following the departure of their ambassadors after the 2020 protests. It would be useful to also have special representatives/envoys appointed in the United States and at the level of the EU and its key states, including Germany, as well as in the UK when the mandate of its ambassador to Belarus ends shortly. These special representatives could coordinate long-term Western policy on Belarus, as well as help to keep the country on their national agendas during periods of decreased media interest in Belarus and the wider region.

Conclusion: A Change of Paradigm

When it comes to Belarus’s current predicament, we must be realistic that there are no likely short-term solutions, especially in terms of what the West can do. If Western countries want to have a positive influence on the trajectory of Belarus’s development, their planning horizon needs to be expanded.

The results of the measures recommended in this paper may only become visible in many years’ time. Or, worse still, and despite all the strategic efforts made and carrots dangled by the West, Belarus may continue to consolidate its authoritarian regime and destroy the remaining sources of independent political activity and thinking within the country. It is not unreasonable to anticipate that Belarusian leaders will submit to the vise-like embrace of deeper integration with Russia for many more years to come, including after both Putin and Lukashenko eventually leave office.

Still, there is only one alternative to devising the long-term—if not the most ambitious—Western strategy proposed in this paper, and that is to continue to have a passive and reactive approach to Belarus. Even with few guarantees of success (particularly in the short term), any efforts that make success more likely in the future are nevertheless movement in the right direction. This is the view the West should espouse in setting its Belarus policy.

Notes

1 For the purposes of this paper, the claims of Putin and Lukashenko that tactical nuclear weapons have been moved to Belarus are taken at face value. There is “no reason to doubt” the claims, CNN cited unnamed U.S. intelligence sources as saying in July 2023. See Natasha Bertrand, “US Intel Officials: ‘No Reason to Doubt’ Putin Claims Russia Has Moved Nuclear Weapons to Belarus,” CNN, July 21, 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/2023/07/21/politics/putin-russia-nuclear-weapons-belarus/index.html. Still, it is important to bear in mind that there has not been any visual confirmation of the claim nor confirmation by other independent sources. Belarusian monitoring groups have only reported the arrival in Belarus of Russian military trains that could have been used to move tactical nuclear weapons or their components. See “What Has Been Heard About TNW in Belarus?,” Motolko.Help, December 7, 2023 (in Russian), https://motolko.help/ru-news/chto-slyshno-pro-tyao-v-belarusi.

2 Treaty between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Belarus on providing joint regional military security (in Russian), https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/international_contracts/international_contracts/2_contract/47455; and Eurasian Economic Union treaty (in Russian), https://pravo.by/document/?guid=3871&p0=f01400176.

3 Treaty between the Republic of Belarus and the Russian Federation on mutual principles of indirect tax liability (in Russian), https://nalog.gov.by/upload/iblock/d05/izibz2wbt8ftwdc8vkoghoq9dguh1wqr.pdf.

4 Belarusians’ Views on the War in Ukraine and Foreign Policy (conducted November 8–14, 2023), Chatham House, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1lojZvBq6Ah4tjDkkLwLIRZx6xqeyCuTW/view.

5 Geopolitical Orientation and Views on the War in Ukraine Among Belarusian Society Broken Down by Level of Education, Belarusian Analytical Workshop (in Russian), https://bawlab.eu/research/310-geopoliticeskie-orientacii-i-vzgady-na-vojnu-v-ukraine-v-belaruskom-obsestve-v-razreze-urovna-obrazovania.

6 Jaroslav Lukiv, “Wagner Mercenaries Have Arrived in Belarus, Ukraine Confirms,” BBC, July 15, 2023, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-66211121.

7 Belarusians’ Views on the War and Value Orientations (conducted March 15–27, 2023), Chatham House, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1T12smHhJBhLv_gzE2FnEfdnFMS_0qujy/view.

8 Emma Levashkevich, “Vardomatskii: Society Is Divided Into ‘No to War’ and ‘There Is No War,’” Deutsche Welle, June 30, 2023 (in Russian), https://www.dw.com/ru/andrej-vardomackij-obsestvo-v-belarusi-razdeleno-na-net-vojne-i-net-vojny/a-66058658.

9 See, for example, John R. Deni, “NATO Must Prepare to Defend Its Weakest Point—the Suwalki Corridor,” Foreign Policy, March 3, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/03/nato-must-prepare-to-defend-its-weakest-point-the-suwalki-corridor; and Richard Milne, “Baltic States Fear Encirclement as Russia Security Threat Rises,” Financial Times, February 20, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/38b1906f-4302-4a09-b304-dc2ecf5dc771.

10 “Lithuanian Ambassador Highlights Great Prospects for Further Development of Viking Container Train,” Interfax Ukraine, November 12, 2020 (in Russian), https://ru.interfax.com.ua/news/general/702860.html.

11 Philipp Bikanau, Konstantin Nesterovich, “Belarusian Identity in 2023 : A Quantitative Study,” Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Ukraine / Project Belarus, December 2023, https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/belarus/20889.pdf; and Belarusians’ Media Consumption, Attitudes to Mobilization and Political Identities (poll conducted November 11–20, 2022), Chatham House, https://en.belaruspolls.org/wave-13.

12 Belarusians’ Views on the War in Ukraine and Foreign Policy.

13 Based on 2022 and 2023 viewership statistics from leading Belarusian independent media and journalist associations in exile, accessed by the author.

14 2020 Schengen Visa statistics by third country, https://statistics.schengenvisainfo.com/2020-schengen-visa-statistics-by-third-country/.

15 “Belarusian GDP Grows 3.9% in 2023,” Interfax, January 17, 2024, https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/98523.

16 Repression in Belarus: Joint Statement to the OSCE, February 2024, February 9, 2024, https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/repression-in-belarus-joint-statement-to-the-osce-february-2024.

17 Belarusians’ Views on the War in Ukraine and Foreign Policy.

.jpg)