INTRODUCTION

Regulatory sandboxes have been used by governments around the world to allow approved fintech firms—which use specialized technological innovations to provide financial products and services—to perform time-bounded experiments with new technologies in regulated environments. The first regulatory sandbox was created in November 2015 by the United Kingdom’s Financial Conduct Authority. Since then, over fifty central banks have implemented the concept in their jurisdictions, according to the Bank for International Settlements.1

Zimbabwe’s fintech regulatory sandbox was established in March 2021 by the National Fintech Steering Committee (NFSC) and is regulated by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ). Its intended responsibilities include testing, enabling innovation, promoting collaboration among participants, monitoring financial technology developments in the country, and supporting innovators in researching.2 Experts have argued that regulatory sandboxes can confer several advantages, including encouraging innovation while allowing policymakers to monitor emerging risks.3 In addition, startup fintech firms typically lack sufficient regulatory expertise, which can become a significant barrier for potential innovators. The sandbox offers both the innovator and the regulator a platform to identify gray areas that could hinder new solutions and test new technology efficiently.

The RBZ has sought to encourage innovation in Zimbabwe’s financial services sector by introducing a regulatory sandbox that allows fintechs to be deployed and tested in live environments without compromising the safety of participants and the financial services market. The bank hopes to foster collaboration between the financial services sector and fintech companies, monitor the development of disruptive technologies, and, in response, implement appropriate safeguards to manage risks and the chances of technology failures that could potentially harm the financial services market. It is anticipated that the new framework will reduce the time to market for approved solutions, and development costs while ensuring consumer protection from bad actors.

The RBZ and relevant government ministries established the NFSC in 2019 to aid the RBZ in managing local fintech innovations. The NFSC is responsible for policy formulation and creating an enabling environment that “promotes financial technology innovation and entrepreneurship.”4 Members of the NFSC include representatives of government ministries, regulators, and the revenue authority. Among the goals of the NFSC is to develop regulatory interventions, including platforms such as innovation hubs, accelerators, and the fintech regulatory sandbox.5

The growth of fintech in Zimbabwe has been immense and can be attributed to digital payments driven by mobile network operators. In a 2018 monetary policy statement, the RBZ reported that 95 percent of all payment transactions in the country were processed digitally—that is, through internet or mobile banking.6 Another notable factor has been the RBZ’s push for interoperability of payment systems across different banks and mobile networks. Accordingly, Zimswitch, the country’s sole national electronic funds switch and clearinghouse, has operationalized a system of interoperability, growing from six banks on the platform in 1994 to over twenty-four participants in 2021.

The phenomenal growth of fintech aside, the economic environment has presented some challenges to doing business in the country. For example, Zimbabwe’s annual inflation rate rose from 3 percent in 2010 to 557 percent in 2021 before dropping to 98.5 percent in 2021.7 The official exchange rate of the country’s currency to U.S. dollars depreciated from 108.67 to 1 in December 2021 to approximately 670 to 1 in December 2022. The erosion in purchasing power has caused strife among suppliers and consumers of products and services. As such, a lack of early-stage financing severely constrains fintech companies operating in the country. In its 2020 report, Financial Sector Deepening Africa noted that fintech startup ideas failed to take off without significant self-financing or the financial support of family and friends.8

Despite the challenging economic environment that has affected Zimbabwe intermittently since 2007 and the global financial crisis of 2008, fintech companies in the country have grown into an alternative to traditional banking. A high mobile connection penetration rate, cash shortages, and initiatives by the RBZ through its National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS) have resulted in the rapid adoption of fintech solutions.

This paper aims to determine whether commonly held views regarding fintech regulatory sandboxes are true or false for Zimbabwe’s local financial services market. This paper discusses the results of a survey conducted in January 2022 by the author—with mixed responses. For example, some participants indicated that they foresaw possible positive improvements in cybersecurity awareness, product development time, and the monitoring of fintech developments in the country. However, there were some reservations regarding the skills capacity of the RBZ to manage the scheme and the protection of intellectual property. The focus areas of the survey conducted by the author on the perceptions of fintech firms participating in the sandbox are provided below.

- Regulatory sandboxes are said to benefit participant firms and consumers of fintech because sandboxes reduce the time-to-market cycle by smoothing the authorization process.

- Regulatory sandboxes provide a platform for monitoring disruptive technologies because fintech activities are new and often are not appropriately covered by existing legislation, requiring legal and regulatory frameworks to adapt. Fintech companies can adjust their solutions following regulators’ concerns at a stage where adaptation costs are still reasonable.

- Regulatory sandboxes provide a platform for collaboration between participants who would otherwise be competitors. Sound supervision, transparency, and enhanced communication with all market participants can further create trust.9

- Regulatory sandboxes potentially increase the vulnerability of consumers and the financial system to cyber risks because vulnerable population groups often lack the skills and experience to use digital financial products and services appropriately. In this regard, fintech could potentially widen the digital divide.

- Regulatory sandbox establishment is not the silver bullet to averting risks posed by fintech because the success of a sandbox depends on several factors, such as coordination and management of the legal mandate, capacity, and maturity of the market regarding the entrepreneurial environment. As a result of a lack of expertise, regulators may overpromise or allow unacceptable levels of risk.10

- Regulatory sandboxes provide a platform on which fintech companies can fundraise for their innovations because if a solution has passed the test of the regulator, this could potentially increase the attraction of the invention for investors, who may feel greater confidence that they are minimizing their investment risk because of the regulator’s seal of approval.

ZIMBABWE’S FINTECH REGULATORY SANDBOX GUIDELINES SUMMARY

The RBZ joins a growing global trend among central banks to implement sandboxes to keep up with innovative financial products and services.

According to the RBZ, establishing the regulatory sandbox was necessary to provide support and an enabling environment that encourages the development of responsible innovation in the financial services sector by providing guidance and standards for the controlled testing of technologies. The objectives and benefits of a regulatory sandbox are listed in table 1.11

| Table 1. Regulatory Sandbox Objectives and Benefits> | |

| Objectives | Benefits |

| Promote safe and responsible innovation of financial products or services to enhance digital financial services' access, usage, and quality. | Ability to test products in a safe and controlled environment. |

| Enable fintech innovation to be deployed and tested in a live environment without compromising on safety for consumers and the financial services sector. | Reduction in time to market at a potentially lower cost. |

| Encourage collaboration between the traditional financial services sector and fintech firms. | Ability to monitor disruptive technologies to ensure that they do not introduce systemic risk to the financial system. |

| Promote competition and efficiency in the financial services sector while protecting consumers. | Support in the identification of appropriate consumer protection. |

| Monitor disruptive technologies to ensure appropriate safeguards to manage risks and contain the consequences of failure. | Provision of avenues for regulatory engagement with fintech firms in the financial services space while contributing to economic growth. |

| Provide an avenue for regulator engagement with fintech firms in the financial services space and inform financial sector regulation and policy. | Stronger foundation for regulatory reforms to meet the changing demands of the financial sector. |

Source: “Fintech Regulatory Sandbox Guidelines,” Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, accessed February 2, 2023, https://www.rbz.co.zw/documents/BLSS/Fintech/FINTECH-REGULATORY-SANDBOX-GUIDELINES.pdf. |

|

The testing phase comprises the following stages: pre-application, application and evaluation, testing, and exit and deployment. The testing stage is limited to a maximum of twenty-four months. The eligible products and services include application programming interfaces, mobile money services, retail payments, cybersecurity products, crowdfunding, and regulatory technology products. Cryptocurrency, digital currency, and central bank digital currency are strictly forbidden. In a 2018 press statement, the RBZ warned the public not to participate in cryptocurrencies, citing the latter’s “opacity and pseudonymous nature” as characteristics that could potentially undermine efforts to combat money laundering and financing terrorism.12 The statement added that no person dealing in cryptocurrency would have any recourse to the RBZ or any other regulatory authority in Zimbabwe.

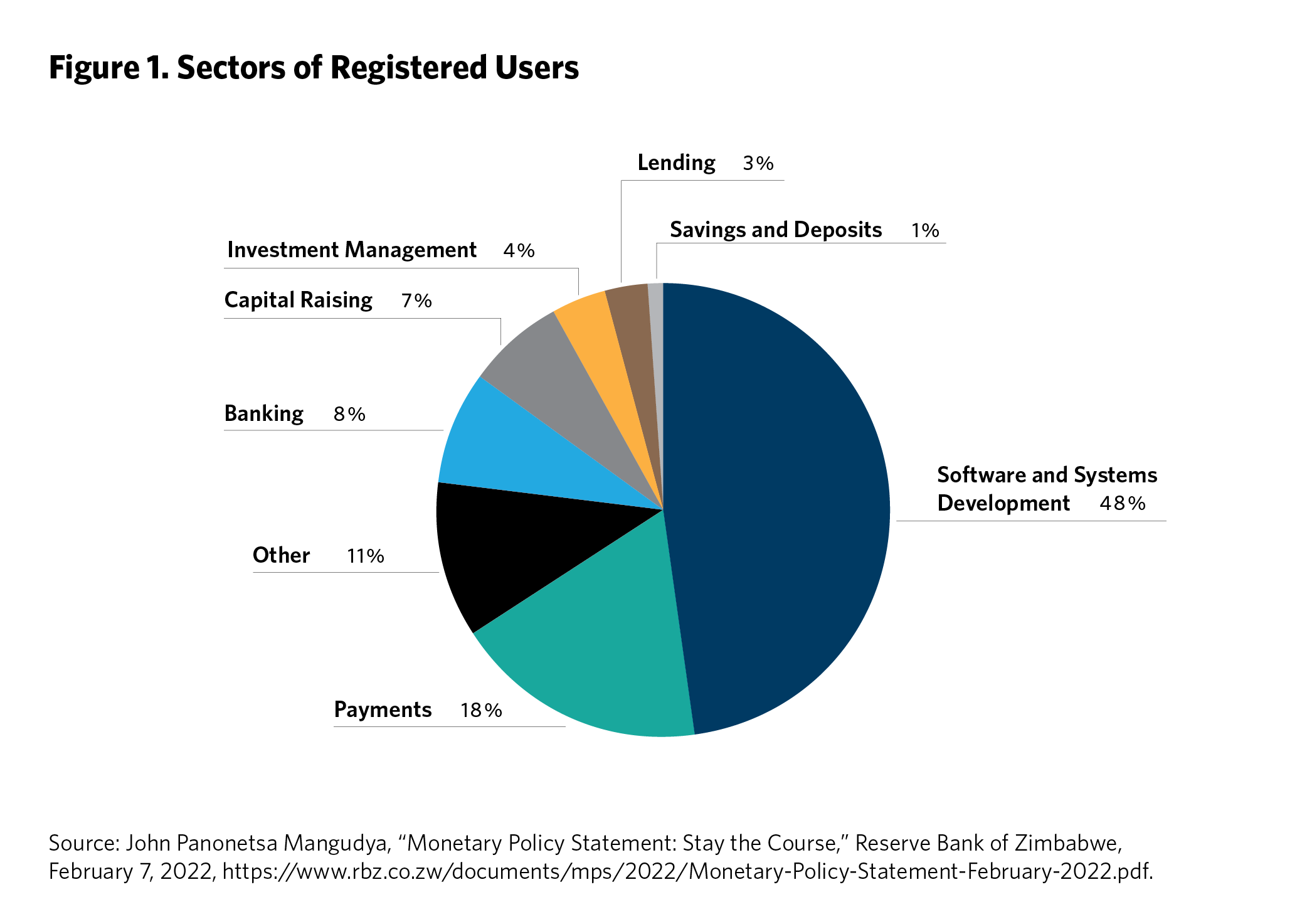

The RBZ advised that as of December 2021, the sandbox had received 112 registrations on the online portal and a further thirty-one applications at various stages.13 As shown in figure 1, registered users came from various sectors, with the largest groups coming from financial services software development (48 percent), payments (18 percent), capital raising (7 percent), and investment management (4 percent).14

SURVEY SAMPLE SELECTION AND RESPONSE RATE

After reviewing the objectives and intended benefits of the sandbox, a questionnaire was developed and distributed to twenty registered participants, using stratified random sampling to identify participants. Sixteen responses were received, constituting an 80 percent response rate (see table 2). The survey was cross-sectional and provided a snapshot at a particular time and place; it was limited to organizations located in Harare because of practical constraints.

The survey sought to determine whether the participants understood or saw the need for the fintech regulatory sandbox. At the time of the initial writing of this paper, the sandbox had been established, but no participants were actively testing their products. In its midterm monetary policy statement of August 2022, the RBZ indicated that it had approved “two financial technology firms into the Fintech Regulatory Sandbox . . . namely Llyod Crowd Funding and Uhuru Innovative Solutions that are providing solutions in capital raising and money transfer, respectively.”15 Notably, these participants were not part of the survey conducted in 2022.

| Table 2. Response Rate of Survey Participants | ||

| Type of Organization | Questionnaires | |

| Sent | Received | |

| Banks | 10 | 7 |

| Micro-banks | 3 | 3 |

| Payments [Switching] | 2 | 2 |

| Insurance | 1 | 1 |

| Mobile Network Operator | 3 | 2 |

| Software Developer [Financial Services] | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 20 | 16 |

| Response Rate | 80 percent | |

SURVEY RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

BENEFITS OF THE SANDBOX TO FINTECH PARTICIPANTS AND CONSUMERS

Respondents were asked whether they saw any benefits to fintech consumers from the sandbox’s establishment. All respondents believed the sandbox would be of immense help to both participants and consumers of fintech because the platform provided a controlled environment to conduct tests under the auspices of the regulator.

UNDERSTANDING THE PURPOSE OF THE SANDBOX

Respondents were asked whether they understood the concept of a regulatory sandbox. All respondents indicated that they understood the definition of a sandbox and its purpose.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A REGULATORY SANDBOX AND AN INNOVATION HUB

The participants were asked whether they believed a regulatory sandbox differed from an innovation hub. All participants thought a regulatory sandbox and an innovation hub were the same.

Participants indicated that they understood the benefits of the regulatory sandbox. However, there is some doubt because none of the survey participants knew the difference between innovation hubs and regulatory sandboxes and because there is currently minimal information in the public domain regarding the regulatory sandbox project. Generally, innovation hubs provide a platform to exchange knowledge and informal guidance, while regulatory sandboxes require the involvement of the authorities. The confusion regarding the definitions implies that the RBZ should explain to participants how these elements are different but not mutually exclusive.

While there is some information regarding the objectives and intended benefits of the sandbox on the RBZ website, and the bank makes periodic pronouncements through monetary policy statements, there has been almost no information shared with consumers of fintech in the public domain; social media and traditional communication platforms could be used to improve understanding of the scheme for fintech firms and consumers of fintech.

It has been noted that transparency and quality communication could potentially increase the attraction of digital innovations to investors, allowing them to assess their investment risk more accurately because of the sandbox. However, adapting existing legal and regulatory frameworks to innovations—often across different ministries, departments, and agencies—can be overwhelming. There is, therefore, an urgent need for market-wide communication to all stakeholders if the regulatory sandbox is to achieve its objectives. The RBZ recognizes this critical need in its recommendations for a new NFIS, or NFIS II, stating that “there is a need to come up with a detailed budget to support financial inclusion initiatives such as financial literacy and consumer awareness campaigns.”16 Tunyathon Koonprasert and Ali Ghiyazuddin Mohammad have made similar observations regarding the need for quality communication between regulators and stakeholders.17

MONITORING OF DISRUPTIVE TECHNOLOGIES

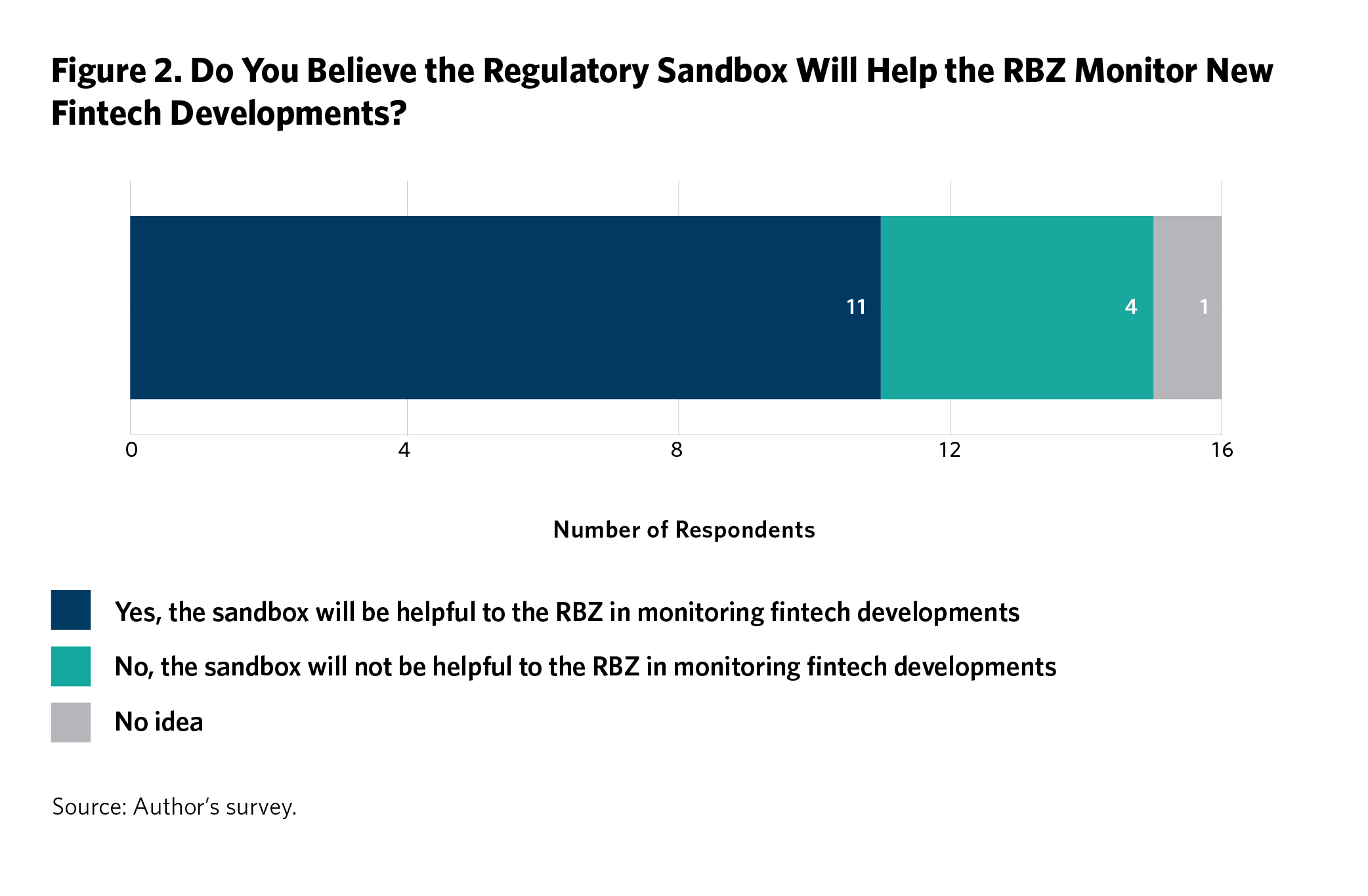

Respondents were asked whether they believed the sandbox would assist the RBZ in monitoring fintech developments (“Yes”), believed the sandbox would not be helpful for this task (“No”), or had no idea either way (“No Idea”). As shown in figure 2, 69 percent responded “Yes,” 25 percent responded “No,” and 6 percent had “No Idea.”

FUNDRAISING AND FUTURE GROWTH

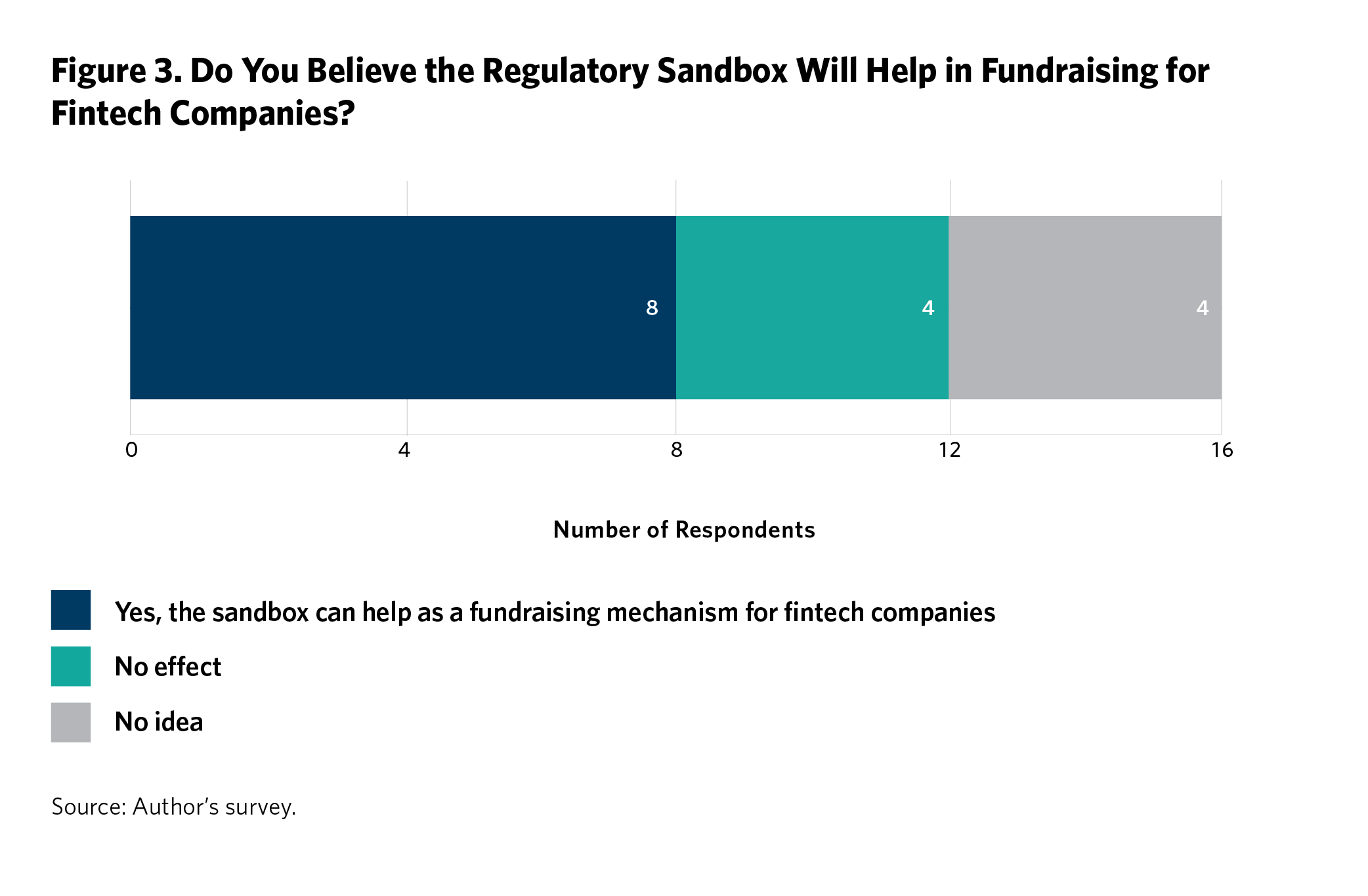

Respondents were asked whether they believed that the sandbox would assist their organizations in fundraising for their innovations or that this was of no effect. Half of the respondents thought that the sandbox could be helpful in fundraising for their creations, while the remainder were evenly split between saying it would have no effect and saying they had no idea (see figure 3).

According to the list of possible benefits identified by the RBZ, assisting companies in fundraising is not one of the objectives of the sandbox. In other markets, participants have leveraged their sandbox participation to attract venture capital companies for funding; if the participants in the RBZ’s sandbox are unaware of this potential, this could be a missed opportunity.

INTERNAL CAPACITY AT THE RBZ

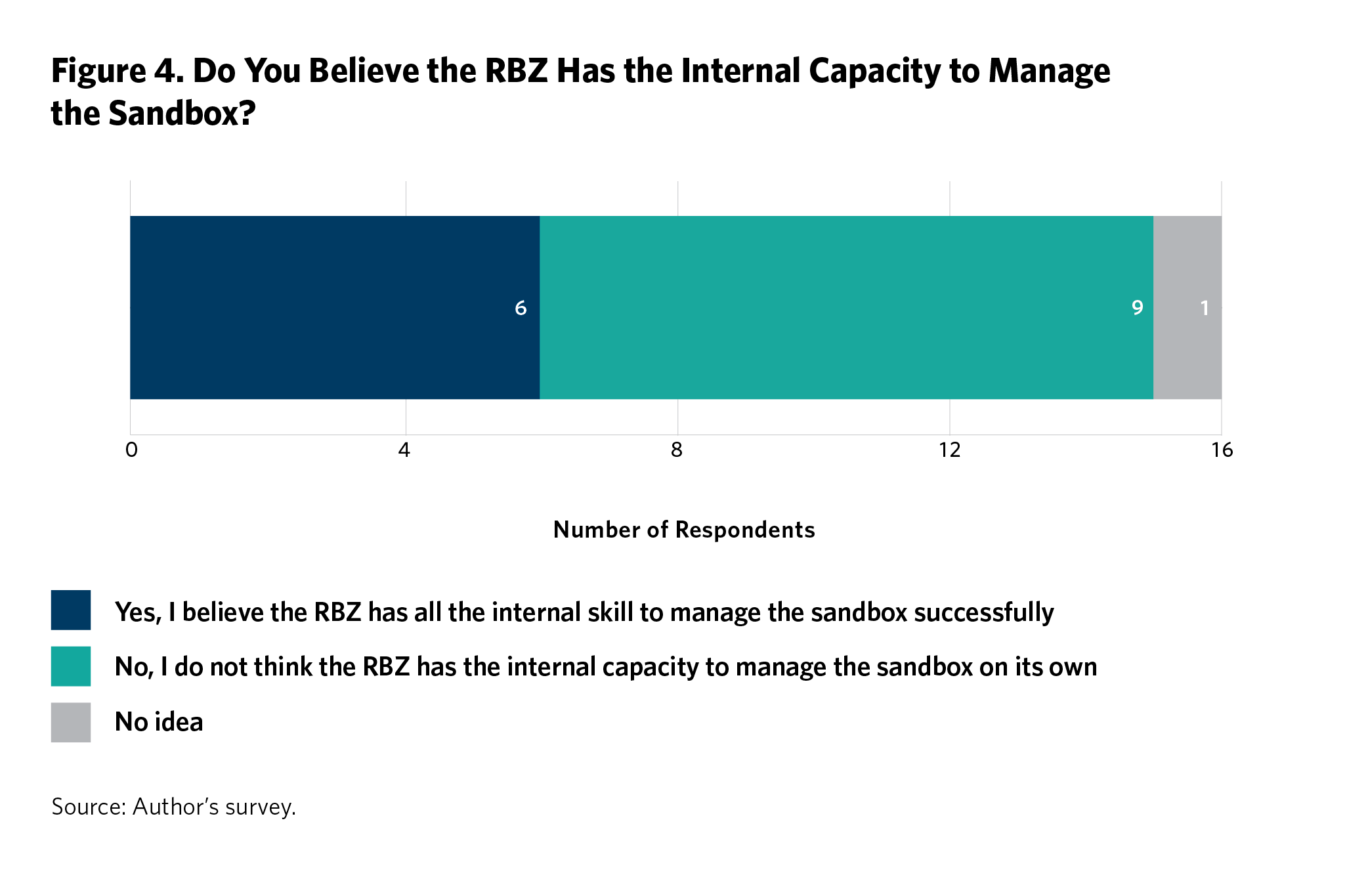

Respondents were asked whether they believed the RBZ had enough resources to manage the sandbox. Most participants thought the RBZ lacked the internal skills to handle the sandbox successfully, as shown in figure 4.

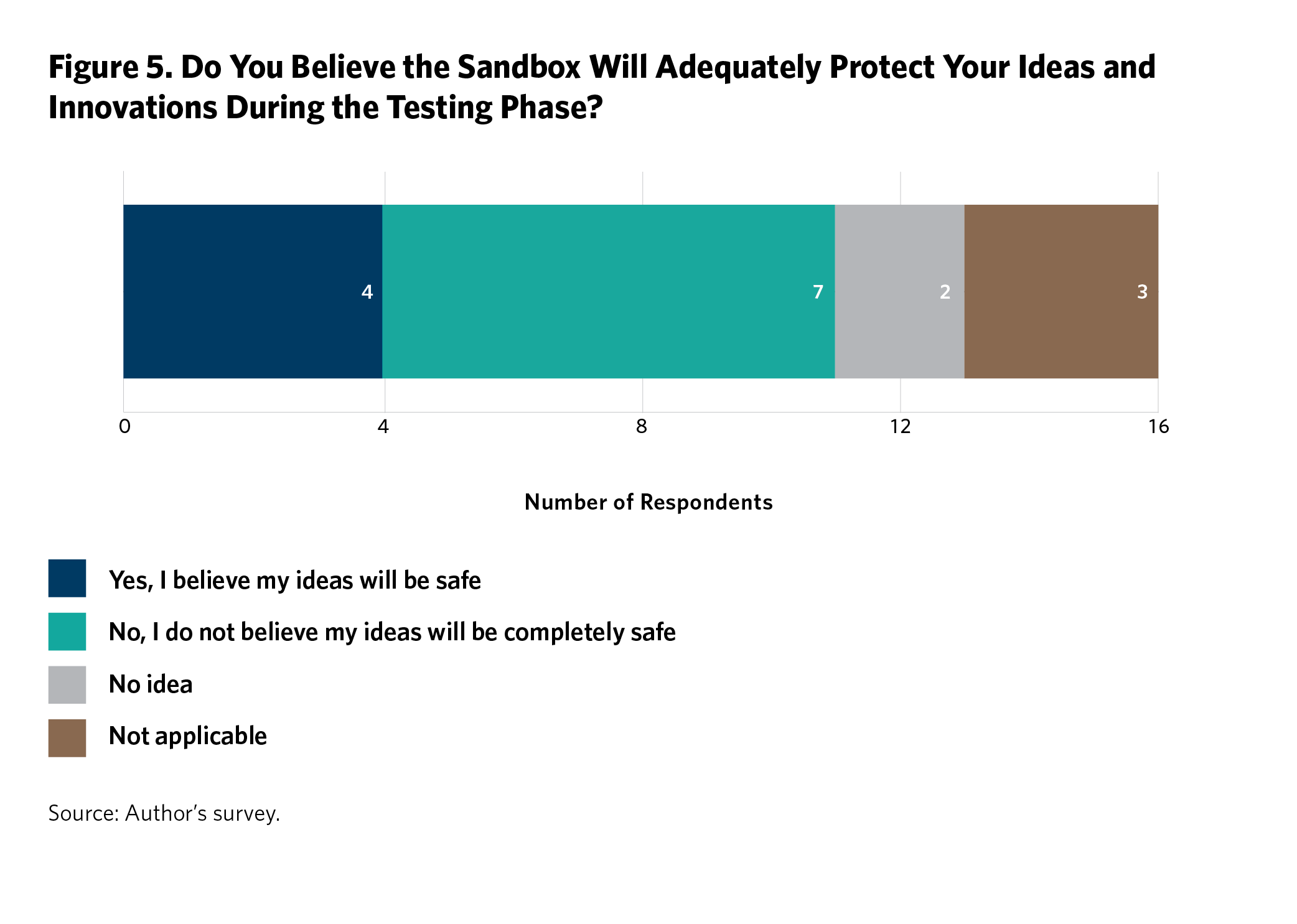

PROTECTION OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Respondents were asked how confident they were in the safety of their ideas and innovations while participating in the sandbox. Most respondents expressed their discomfort regarding information confidentiality (see figure 5).

There were some reservations regarding whether the RBZ had the internal capacity to manage the sandbox adequately. Similar sentiments were expressed regarding the confidentiality or the safety of ideas in the sandbox. To its credit, the RBZ has constituted the NFSC and Interagency Fintech Working Group (IFWG) that will oversee the development of fintech companies in Zimbabwe, including best practices and regulatory responses, and provide recommendations to the NFSC. This is a laudable step; the IFWG can detect possible conflicts of interest early while bringing a more comprehensive range of skills to the NFSC. The NFSC comprises representatives from various stakeholders, including the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development; the Ministry of Information Communication Technology and Courier Services; the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority; the Securities Exchange Commission of Zimbabwe; the Ministry of Industry and Commerce; the Ministry of Justice, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs; the Office of the President and Cabinet; the RBZ; the Insurance and Pensions Commission; and the Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe.18

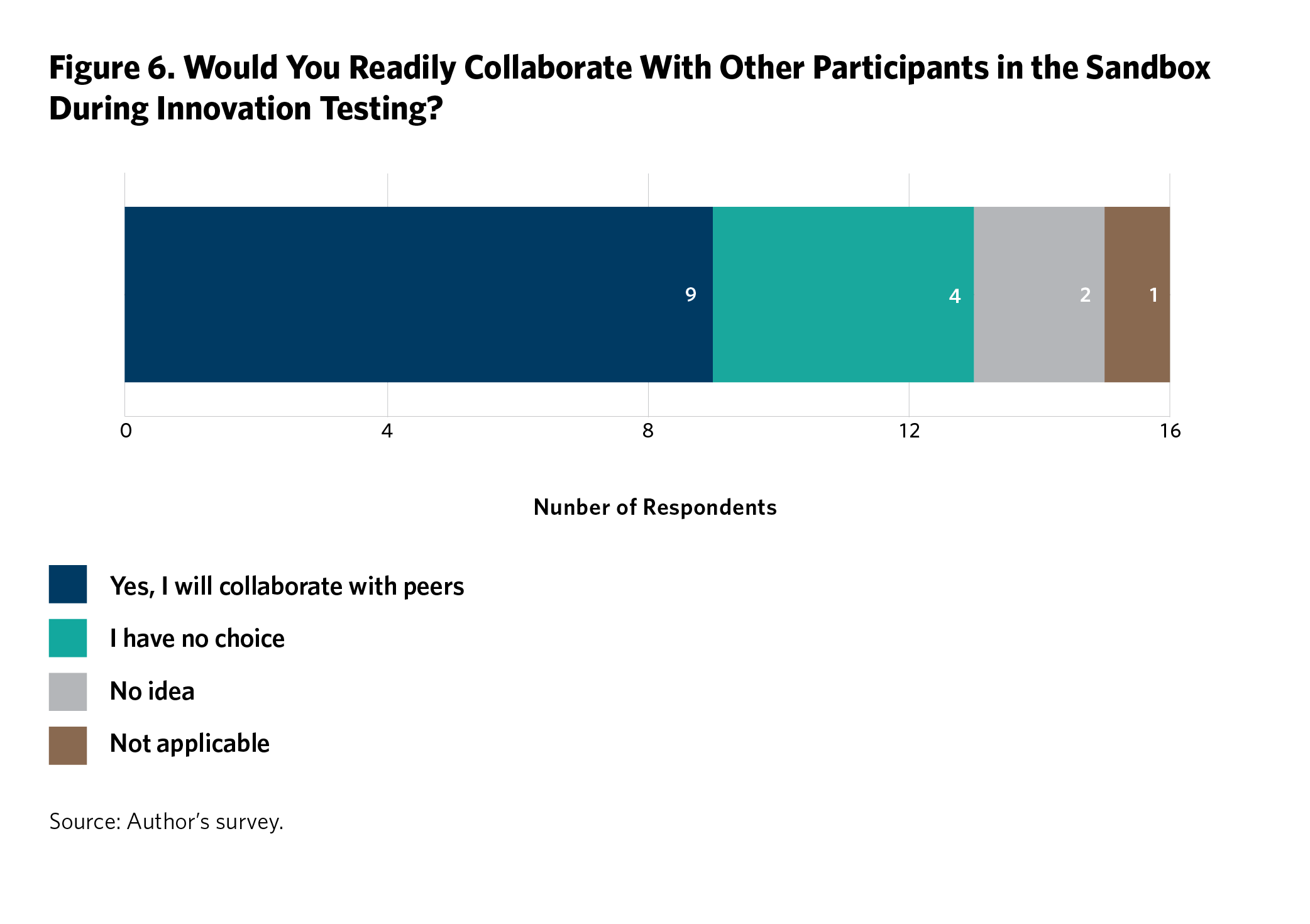

COLLABORATION

Respondents were asked whether they would readily collaborate with their peers in developing or refining their innovations. Most participants indicated they would be willing to share ideas with other sandbox participants (see figure 6).

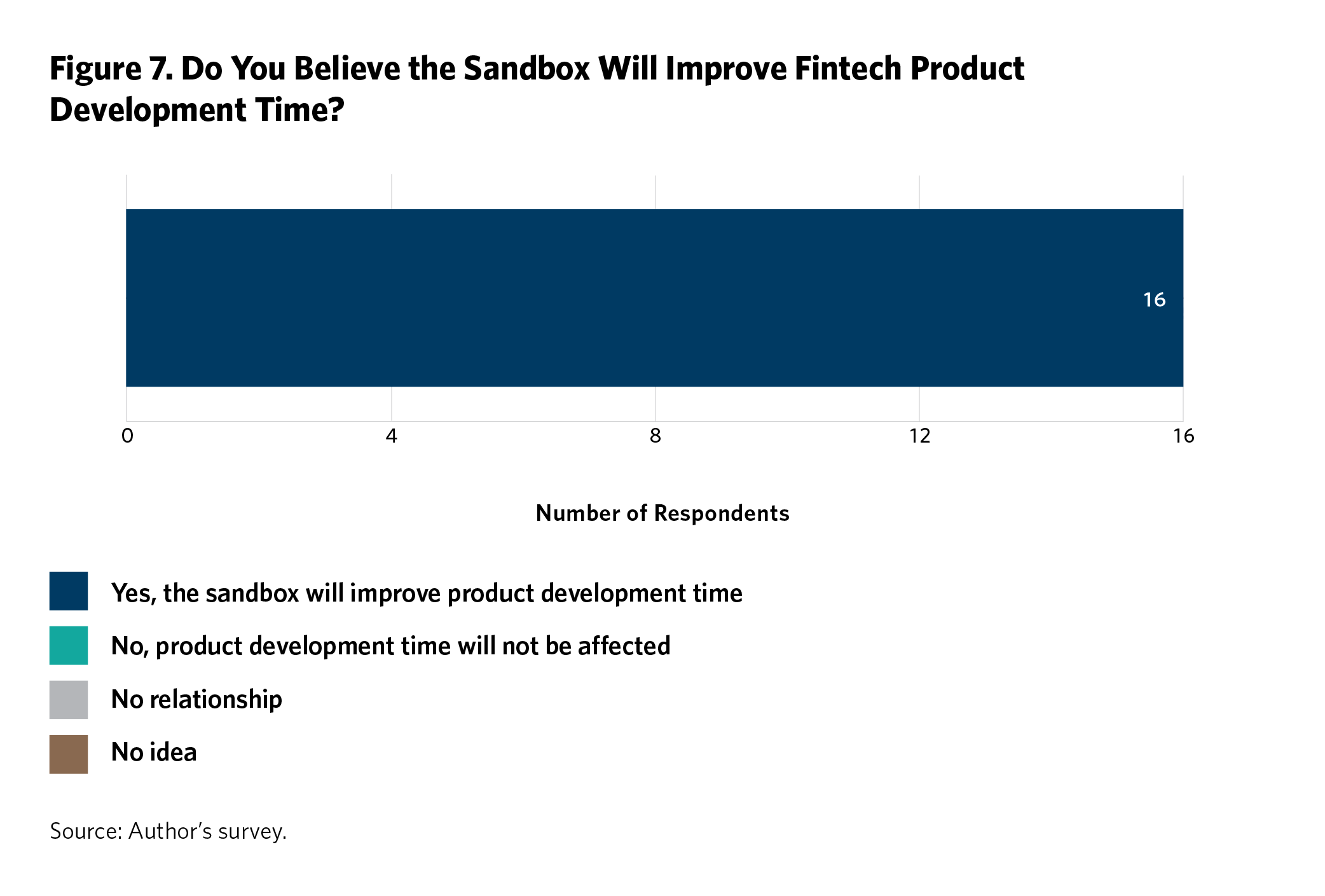

PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

Respondents were asked whether they believed the sandbox could help reduce product development time. As shown in figure 7, all participants thought it would. They also indicated that they would be willing to collaborate with peers in developing or refining their innovations through engagement within the sandbox. Most participants believed the sandbox would assist the RBZ in monitoring fintech developments (see figure 2). These responses are good news for developing safe, innovative digital financial services and products.19

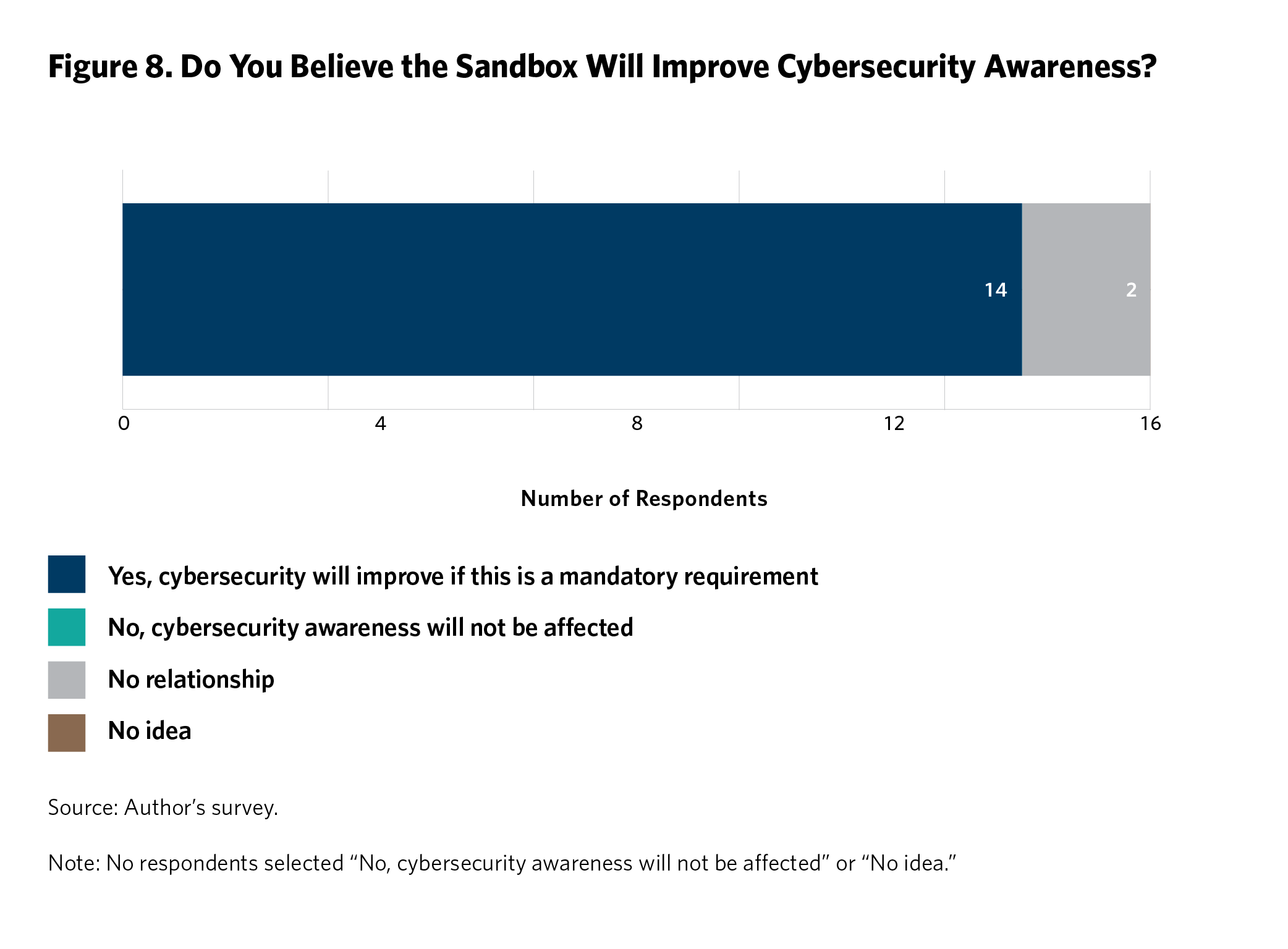

CYBERSECURITY AWARENESS

Respondents were asked whether they thought the regulatory sandboxes could be used to improve cybersecurity awareness among consumers of fintech products. As shown in figure 8, 87 percent believed this was possible only if the RBZ insisted on cybersecurity awareness before launching fintech solutions, and 13 percent saw no relationship between cybersecurity and the regulatory sandbox. Respondents were offered the option to select an answer saying that the sandbox would not affect cybersecurity awareness, but no respondents chose that answer.

Most participants saw a correlation between cybersecurity and the regulatory sandbox, but they believed the regulator needed to make cybersecurity awareness a requirement during the testing phase. Ideally, the RBZ must provide oversight on cybersecurity for fintech products and services and encourage participants to embrace the secure-by-design concept.

Managing how customer data is handled is vital because of the systemic risks that could arise from digital innovation failures.20 The supportive responses from participants should be welcome news to the RBZ and NFSC, as one of the objectives of the sandbox is to ensure the safety of fintech consumers. It is in the best interest of well-resourced, technologically savvy institutions like banks and fintech companies to overcome the competitive pressures among them and extend cybersecurity to protect consumers of financial and digital services, who may be less savvy and more vulnerable. Put simply, a robust system makes everyone safer.

CONCLUSION

This paper explored factors that could significantly impact the success or failure of Zimbabwe’s newly established fintech regulatory sandbox. The regulator and the sandbox participants hope that the sandbox will provide information on new fintech solutions in the market; identify early possible disruptive technologies that have the potential to cause systemic risk in the market; create proximity and a direct interface between the regulator and market participants; reducing development time and the time to market of solutions (saving costs); assist sandbox participants in convincing investors to fund their innovations; and bolster cybersecurity within the emergent digital financial landscape and protect consumers of fintech products and services.

The success of the regulatory sandbox, however, hinges on several factors. Key among these is quality communication with and education of the various stakeholders in the digital financial services space, which is necessary and urgent.

The government of Zimbabwe needs to stabilize the economy. While commendable progress has been achieved in financial inclusion and digital innovation, much still needs to be done. Small and up-and-coming fintech companies do not have the financial muscle to manage the frequent upswings and downswings Zimbabwe’s economy is currently experiencing; these could result in a brain drain of some of the country’s best minds.21 The notion of skill loss is aptly summed by fintech scholar Hilary J. Allen, who postulates that “the market for fintech products and services does not respect national borders, with many of these solutions being developed and deployed simultaneously in different markets.”22

The regulatory sandbox is not a novel concept and has been implemented in many jurisdictions globally. However, the success of Zimbabwe’s sandbox is yet to be adequately quantified. Whether the regulatory sandbox will succeed or fail and which areas will require refinement remains to be seen.

NOTES

1 Giulio Cornelli et al., “BIS Working Papers No. 901: Regulatory Sandboxes and Fintech Funding: Evidence From the UK,” Bank for International Settlements, 2023, https://www.bis.org/publ/work901.pdf.

2 “Fintech Regulatory Sandbox Guidelines,” Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, accessed February 2, 2023, https://www.rbz.co.zw/documents/BLSS/Fintech/FINTECH-REGULATORY-SANDBOX-GUIDELINES.pdf.

3 “Understanding the Importance of Regulatory Sandbox Environments and Encouraging Their Adoption,” African Development Bank Group, 2022, https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/afdb_regulatory_sandbox_report_220522.pdf.

4 “Fintech Institutional Arrangements,” Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, accessed November 22, 2023, https://www.rbz.co.zw/index.php/fintech/1066-institutional-arrangements.

5 The Financial Stability Board defines fintech as “technologically enabled financial innovation in financial services that could result in new business models, applications, processes or products with an associated material effect on financial markets and institutions and the provision of financial services.” See “FinTech,” Financial Stability Board, May 5, 2022, https://www.fsb.org/work-of-the-fsb/financial-innovation-and-structural-change/fintech/.

6 “Monetary Policy Statement: Strengthening the Multi-Currency System for Value Preservation & Price Stability,” Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, October 1, 2018, https://www.rbz.co.zw/index.php/publications-notices/notices/press-release/568-monetary-policy-statement-01-october-2018.

7 “Zimbabwe,” World Bank Data, accessed May 1, 2023, https://data.worldbank.org/country/ZW.

8 “Zimbabwe Fintech Ecosystem Study,” Financial Sector Deepening Africa, March 25, 2020, https://www.fsdafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Zim-Fintech-Report-25.03.20_FINAL.pdf.

9 Wolf-Georg Ringe and Christopher Ruof, “Regulating Fintech in the EU: the Case for a Guided Sandbox,” European Journal of Risk Regulation 11, no. 3 (September 2020): 604–629.

10 Dirk A. Zetzsche, Ross P. Buckley, Janos N. Barberis, and Douglas W. Arner, “Regulating a Revolution: From Regulatory Sandboxes to Smart Regulation,” Fordham Journal of Corporate and Financial Law 23, no. 1 (2017): 31.

11 Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, “Regulatory Sandbox Guidelines.”

12 “Press Statement Warning Against Trading in Cryptocurrencies,” Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, May 2018, https://www.rbz.co.zw/documents/BLSS/BANK%20SUPERVISION/Press%20Releases%20&%20Speeches/2018/PRESS%20STATEMENT%20ON%20WARNING%20AGAINST%20TRADING%20IN%20CRYPTOCURRENCIES%20%20%20-%2011%20May%202019.pdf.

13 John Panonetsa Mangudya, “Monetary Policy Statement: Stay the Course,” Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, February 7, 2022, https://www.rbz.co.zw/documents/mps/2022/Monetary-Policy-Statement-February-2022.pdf.

14 Mangudya, “Stay the Course.”

15 John Panonetsa Mangudya, “Mid-Term Monetary Policy Statement: Restoring Price and Exchange Rate Stability,” Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, August 11, 2022, https://www.rbz.co.zw/documents/mps/2022/Monetary-Policy-Statement-August-2022-.pdf.

16 “Zimbabwe National Financial Inclusion Journey 2016-2020,” Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, 2021, https://www.rbz.co.zw/documents/BLSS/2021/FINANCIAL-INCLUSION--JOURNEY.pdf.

17 Tunyathon Koonprasert and Ali Ghiyazuddin Mohammad, “Creating Enabling Fintech Ecosystems: The Role of Regulators,” Alliance for Financial Inclusion, https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/publications/2020-01/AFI_FinTech_SR_AW_digital_0.pdf.

18 Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, “Fintech Institutional Arrangements.”

19 Marta Barroso and Juan Laborda, “Digital Transformation and the Emergence of the Fintech Sector: Systematic Literature Review,” Digital Business 2, no. 2 (2022): 100028, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.digbus.2022.100028.

20 Koonprasert and Mohammad, “Creating Enabling Fintech Ecosystems.”

21 Financial Sector Deepening Africa, “Zimbabwe Fintech Ecosystem Study.”

22 Hilary J. Allen, “Sandbox Boundaries,” Vanderbilt Journal of Engineering and Technology Law 22 (2019): 299, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3409847.

.jpg)