Since the September 16, 2022, death in police custody in Tehran of twenty-two-year-old Mahsa Jina Amini, who had been arrested for not wearing the hijab in accordance with government rules, a revolt has gripped the whole of Iran. Iranians from all walks of life are protesting against a regime built on the institutionalized oppression of women and systematic violations of women’s and human rights. The regime has reacted with lethal violence and arbitrary arrests while doubling down on the persecution of civil society actors and women’s and human rights defenders.

Feminist foreign policy demands both short-term interventions and a long-term approach to these gross violations of human and women’s rights by a repressive regime. The EU should therefore support immediate efforts to document and verify the massive rights violations to hold those responsible accountable as well as to safeguard digital rights and protect rights defenders. A durable exchange with Iranian civil society, in turn, would allow future policy decisions in the EU to be aligned with gender-aware priorities. And EU policymakers should closely monitor and, wherever possible, minimize the impact of sanctions on the Iranian civilian population.

From Women’s Protests to a Feminist Response

As a fundamentalist Shia theocracy, the Islamic Republic of Iran has systematically subjugated women and minorities, especially religious ones, since 1979—despite the country’s basic democratic elements, such as regular elections and limited pluralism in public opinion. Over the past years, hardliners have steadily consolidated their power, which has been accompanied by further backsliding on women’s rights and mounting economic hardships. Meanwhile, discontent has been simmering below the surface, regularly erupting in the form of strikes of teachers and truck drivers, protests over water scarcity and unpaid wages, or riots over rising fuel prices.

Today’s revolutionary process ignited over Iran’s legal requirement to wear the hijab but soon focused on broader gender-based injustices and now plainly demand equality, life, and freedom for women—and, indeed, all Iranians. Women have mobilized in previously unknown ways and continue to largely carry the protests. While it is unclear where this unrest will lead, it is already the most significant disruption the regime has witnessed in over four decades: the people in the streets might not be as numerous as in the 2009 Green Wave, but the current revolt is more widespread throughout the country, more defiant in its nature, and more threatening in the chants of “death to the dictator.” Many Iranians in and outside the country hope this will be a truly Iranian revolution, doing away with the previous, Islamic one.

Outside powers like the EU are therefore exploring what they can do in response: how to alleviate the suffering of Iran’s civilian population; whether and how they can halt the state’s violence against its own citizens; and, more fundamentally, whether they can help events move in a democratic, rules-based direction. Already, citizens in Europe are calling for a more substantial, more forceful response from their governments as an expression both of a credible, value-oriented foreign policy and of their countries’ own interests. Those EU member states that pursue a feminist foreign policy feel a particular urge to act, not least because European public opinion and domestic opposition parties demand concrete action from this still fairly new approach.

Feminist foreign policy builds on decades of feminist activism, theoretical research, and practical application. It is therefore no wonder that there is no unified school of thought on what constitutes such a policy. At its core, however, are human security, human rights, and a particular focus on structural inequalities as drivers of conflict not only between genders but also beyond. Even as the contours of feminist foreign policy remain contested among those—be they governments, scholars, or activists—who are developing or applying the concept, two points illustrate what it is and what it is not.

First, the feminist approach is not a panacea that can be easily applied to undo structural power imbalances and neutralize the deep-rooted drivers of conflict and marginalization. Instead, it is about understanding a given problem more comprehensively to then act purposefully and use existing and new instruments in a targeted manner. Crucially, this approach is not suddenly relevant because women are taking to the streets in Iran but because it appears promising given the social and political complexities behind the revolt. In fact, reducing the feminist approach to one that is applicable only when women’s rights are under attack undermines the holistic character of this framework.

Second, any feminist approach begins at home. This means that it cannot be limited to the implementation of policies to address external issues but needs to also focus on how those policies are developed internally: Who is affected by a given policy and therefore needs to be heard—and which voices are underrepresented? Who should sit at the table when decisions are made? Where is the money going? An often heard criticism that the feminist approach is failing the women in Iran falls flat if it comes from actors who oppose feminist values at the domestic level. It is simply contradictory to get upset about the politicization by men of women’s clothing in another part of the world but to deny effective equal rights, including women’s bodily autonomy, in one’s own society.

Surely, the question must be how best to support women—and all people—in Iran, especially those risking their lives in the streets protesting for freedom and dignity. It would be shortsighted, however, to blame feminist foreign policy for not producing an easy response to a long-standing autocratic and repressive regime, or for not coming up with a quick but thorough policy fix after the EU has for years focused on Iran’s nuclear program.

These caveats notwithstanding, while a feminist foreign policy is, in large part, about doing things better in the long run, it does hold concrete recommendations for a more comprehensive and substantial approach.

A Practical, Three-Pronged Approach

The first attempt to translate feminist foreign policy into government action came in 2014 from Sweden, which developed the three Rs formula of rights, representation, and resources. Under this model, foreign policy should be guided by how it affects the realization of women’s and universal human rights, the representation of women and other marginalized groups in political decisionmaking, and the gender-equal distribution of and access to resources. All of this should be based on people’s lived realities.

Over the years, this concept has seen some important developments, for example through a broader focus on gender and other discriminating factors, rather than on women more narrowly. Building on this work, the German government added diversity as a cross-cutting issue (3R+D) when it introduced its feminist approach in late 2021. The underlying idea was that the more diverse and inclusive decisionmaking processes are—whether in terms of the implementation of rights, questions of representation, or the distribution of resources—the more sustainable the decisions themselves become, as they avoid the usual blind spots.

This emphasis on diversity builds on an understanding of feminist foreign policy as one that embraces intersectionality, which refers to the situation of those facing multiple forms of discrimination, such as women in a minority. Such an approach detects patterns of exclusion that derive from structural power imbalances.

Rights

Given the Iranian state’s persistent repression, an EU response based on a feminist foreign policy must, above all, respond to the enormous violations of children’s, women’s, and human rights. These violations include massive violence against demonstrators, arbitrary arrests of protesters and rights defenders, and inhumane prison conditions. The system does not only target women: other marginalized groups, such as the Kurdish and Baluchi minorities, the Baha’i religious community, and Afghan refugees, are also particularly attacked. The EU response should dedicate special attention to the high share of minors being killed in the protests—around 15 percent of all confirmed deaths as of this writing.

The current crisis is not an isolated incident but the product of the long-established suppression of women’s rights, which is built into the Iranian political system. In theory, the Iranian constitution guarantees equal protection under the law and the enjoyment of all human rights for men and women. Iran is also party to international human rights instruments that uphold equality for women and nondiscrimination. Yet in reality, laws and social practices severely limit women. Not only do Iranian laws fail to protect women from discrimination or physical harm, but the regime also negates equal rights for men and women when it comes to personal status, family law, and civil, political, or socioeconomic rights. And Iran has not ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the key international instrument aimed at ensuring gender equality.

Far beyond the matter of the mandatory hijab, the Iranian legal code includes several discriminatory provisions that directly limit women’s agency. These institutionalized barriers severely restrict women’s lives, bodily autonomy, and livelihoods. Those who experience intersecting discrimination because of their minority background or social status are impacted even more strongly. Aggravated by the coronavirus pandemic and the consolidation of hardline power over recent years, this discriminating setup creates stark civil, political, and socioeconomic inequalities.

Dire as the human and women’s rights situation in Iran is, it has received little attention abroad, as the issue of the country’s nuclear program—embodied in the suspended 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—has dominated European policy for years. At the same time, nuclear nonproliferation—that is, freedom from an immediate nuclear threat—is a human right in itself and central to the concept of human security. A feminist approach, therefore, does not entail abandoning nuclear diplomacy with Iran as such; instead, it suggests that human rights should feature in negotiations and diplomacy as another central political priority.

The current situation nonetheless presents the EU—as well as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom as the three European signatory countries in the JCPOA—with a dilemma: Should they proceed with negotiations on restoring the nuclear deal if and when Tehran is willing to compromise on the remaining roadblocks? Or should they call off the talks in the face of the regime’s brutal crackdown? Concluding the talks now would give Tehran international recognition and embolden the regime rather than the protesters who need support. It is of little comfort that even a revived JCPOA would not be a gift to Iran but would come with increased inspections and reintroduced restrictions for the country’s nuclear program. Still, this scenario is not imminent: not only had diplomatic efforts stalled before the beginning of the current revolt, but Iran also upped its nuclear gambit by refusing the EU’s August 2022 proposal for compromise and further increasing uranium enrichment in November, making any accord unimaginable at the moment.

In any case, ending the nuclear talks would be largely symbolic and have no positive effect on the human rights situation on the ground. Worse, without a plan B on how to deal with the nuclear threat in the absence of an agreement, breaking off the discussions would violate the human right to live free from a nuclear attack. Nonetheless, the singular focus on the nuclear file over the last decade has led the EU to disregard important aspects of human rights promotion and civil society support.

Representation

In the context of the current revolt, representation aims to allow the most affected groups to be actors in their own right and give them a say in policies to address the crisis. This means EU policymakers listening to the voices of Iranian civil society, be they from Iran or mediated through diaspora interlocutors and organizations abroad.

Formal political processes in Iran prevent the participation of women and marginalized groups in much of the political system. While there are some female members of parliament and government ministers, women are barred from running for president or becoming judges. At the same time, minorities are excluded from most parts of political life. On the one hand, Shia-majority Iran discriminates even against Sunni Muslims, let alone religious minorities like the Zoroastrians or the Baha’is, who suffer from ever-increasing systemic persecution. On the other hand, ethnic minorities in Iran’s periphery face socioeconomic hardships through neglect and mistrust because of their suspected ties to neighboring countries.

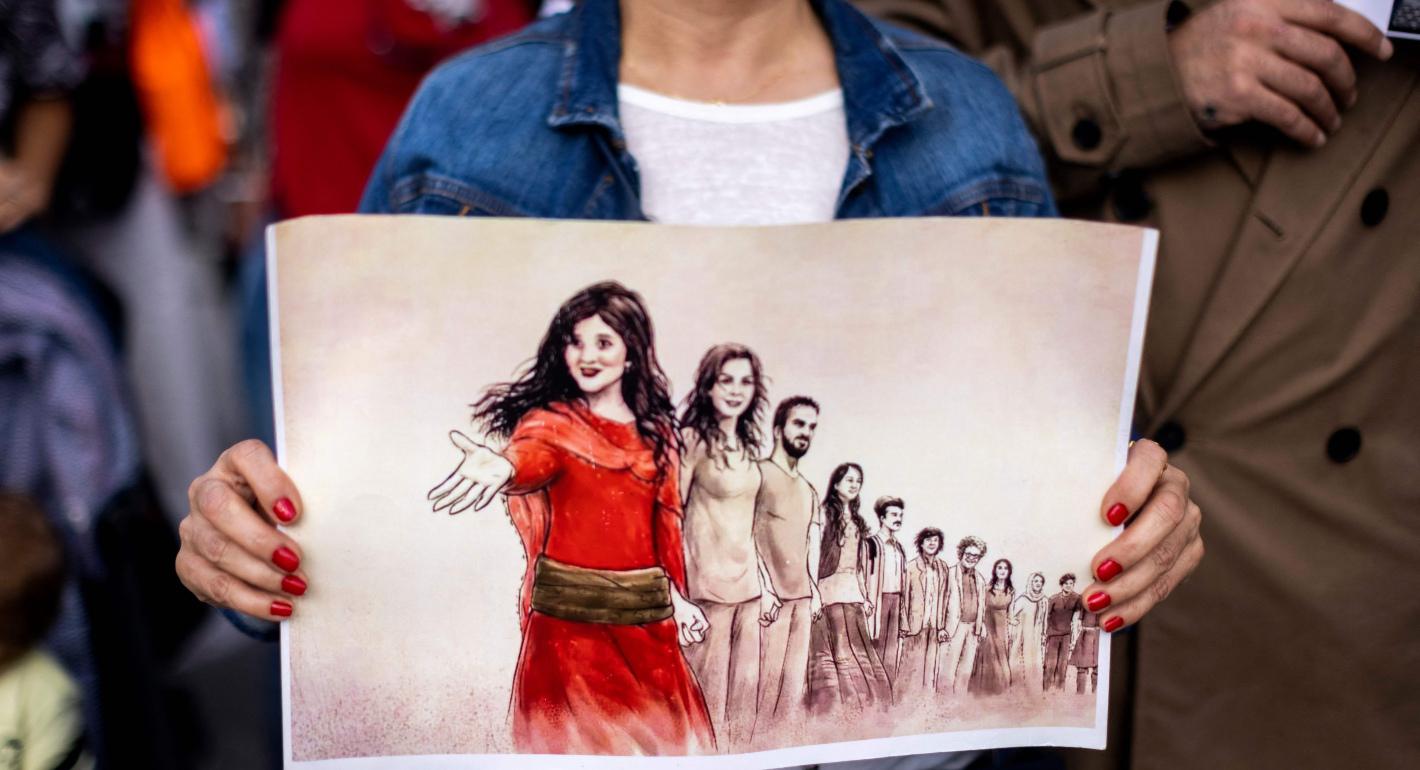

Despite decades-long systemic discrimination, however, women are agents of social change in Iran. They have mobilized Iranian citizens, regardless of their gender, age, class, or religious or ethnic background, to join this revolutionary process. This widespread influence is most visibly illustrated in an originally Kurdish protest slogan, now commonly adopted in its Persian version, that puts the word jin or zan (woman) first. Even though the most violent repression has taken place in the country’s peripheral regions—Kurdistan in the northwest and Sistan and Baluchistan in the southeast—there have been no calls from protesters for these regions’ secession.

Feminist foreign policy emphasizes the importance of diversity in political decisionmaking at the individual level as well as through civil society. In doing so, it does not negate national security concerns but criticizes the predominance of state actors. Especially the single focus on the nuclear file excludes most civic agency at the EU or international level and gives little attention to the priorities of the Iranian population. In addition, the repressive national context creates further hurdles to support and engage with civil society voices at the international level.

A major challenge for the formulation of a European policy toward Iran is the information gap in the absence of an EU delegation on the ground. This makes it even more necessary to recognize civil society expertise as a resource that would allow the EU to develop a gender-aware focus on the priorities of the Iranian people. This gap also underscores the importance of EU member states’ delegations in Iran not only for consular services but also for political reporting, including on human rights. At the same time, the diverse, sometimes contradictory interests of diaspora groups and their tendency to rally around individuals rather than build reliable opposition structures require a differentiated approach.

Therefore, working with, supporting, and strengthening civil society networks through interactions with EU government actors would be a good step. At a time when the EU and its member states are zooming in on the importance of supporting pro-democracy civic actors in a context such as Iran’s, a structured and trusted platform for such a dialogue might be a well-placed instrument to promote and protect women’s and human rights in the country. This could allow EU policymakers to ask what civil society’s needs are and undertake a reality check of the EU’s current approach. Civil society experts could voice their priorities and contribute to a more comprehensive policy framework.

Also, those civil society activists who maintain links into Iran can provide information for EU policymakers that European embassies in Tehran and EU member states’ foreign ministries do not have. This intelligence could include needs assessments and encompass more broadly developed, gender-aware policy analyses. Moreover, a regular dialogue with civil society representatives on issues of citizens’ concern—health, labor, the environment—would provide original information on political challenges that could be easily overlooked from a Brussels-based perspective.

Resources

Feminist foreign policy postulates gender-aware access to and distribution of resources. This concerns the allocation of financial resources as much as access to information and the bases on which budgetary decisions are made.

Regarding the allocation of resources, the EU Gender Action Plan III on gender equality in EU external action stipulates that 85 percent of all new external actions should contribute to gender equality by 2025. Accordingly, the European Commission aims to strengthen gender-responsive budgeting. This goal then needs to be translated into individual budgetary allocations in country-specific and thematic programming on Iran, civil society support, and the strengthening of human rights.

In the case of Iran, both the EU’s 2021–2027 Multiannual Indicative Program for the country and the Global Europe Human Rights and Democracy program put forward specific budgets, for example to support civil society or strengthen human rights. The latter category is characterized by the fact that funding can be awarded without the consent of the respective government. Yet, few funds have been allocated, because of Iran’s repressive environment and the EU’s diplomatic restraint toward the country.

In terms of access to information, the importance of digital rights in Iran as well as channels of communication and engagement with civil society experts become all the more relevant.

Principles of a European Response

An EU policy toward Iran based on a feminist approach should prioritize actions of immediate importance, such as protecting Iranians against rights violations, fostering greater representation of civil society actors, and channeling resources in more effective ways. Such a policy should also emphasize the medium- and long-term perspectives of addressing the underlying challenges in an authoritarian, patriarchal system.

Support Rights Organizations and Protect Rights Defenders

Given the grave situation in Iran, in general and during the ongoing revolt, the EU should focus on an intersectional perspective on women’s and human rights violations. This includes ensuring accountability for acts of violence and repression, focusing on digital rights, and protecting rights defenders.

Precisely because neither the EU nor its member states can intervene to directly protect those affected, they should push for the documentation and verification of crimes as well as the accountability of those who committed them. This applies to the death of Amini at the origin of the protests as well as to the violent crackdown by security forces since then. A meaningful examination of the Iranian state’s brutality would undoubtedly reveal further patterns of systematic repression, such as the deliberate targeting of young people, including minors, to deter their peers and of ethnic minorities in the country’s peripheral regions to quell the unrest.

To this end, the EU should financially and technically support women’s and human rights organizations that record rights violations in the country so that those responsible can later be prosecuted. It is important to provide as comprehensive an account as possible of all political prisoners and the conditions of their detention as well as possible crimes of sexual and gender-based violence.

The EU should work closely with the UN and its non-Western member states to ensure the effective work of the independent fact-finding mission mandated in November 2022 by the UN Human Rights Council. Ideally, the mission would cooperate with a trusted domestic institution, such as the Iranian Central Bar Association. Coordinating closely, EU and UN human rights mechanisms should examine the possibility of equipping the UN special rapporteur on human rights in Iran with additional means and expanding their mandate to emphasize accountability for current crimes and human rights violations. A joint resolution, or mirroring ones, by the UN Human Rights Council and the EU Foreign Affairs Council would be an important step in this direction beyond the symbolic effect of holding an extraordinary session of each council to discuss the revolt.

To ensure credibility and send a strong message, the EU should place particular emphasis on including voices and countries from the Global South in the process of formulating such a coordinated response. The Joint Statement on the Equal Condition and Human Rights of Women following the death of Amini—an effort led by Chile, supported by more than fifty UN member states, and passed in the September 2022 session of the UN Human Rights Council—is a welcome example.

To hold those in the Iranian regime who are responsible for rights violations directly accountable, targeted EU sanctions are the right step. Even if they do not necessarily change the perpetrators’ behavior, sanctions would make their offenses known internationally. Those who should be sanctioned include the commanders of the security forces who are leading the crackdown, be they regular police, the Revolutionary Guards, or the Basij militia, as well as the 227 members of the Iranian parliament who called for the death sentence for the protesters. The principle of universal jurisdiction also offers the possibility of holding alleged perpetrators accountable according to the rule of law. The 2020 Syrian state torture trials in Koblenz, Germany, and the 2022 guilty verdict for an Iranian official in Sweden are significant reference points.

The comprehensive internet and cellphone blockages in Iran imposed by the regime as part of the crackdown impede communication among protesters and global reporting. It is therefore even more important that sanctions be imposed on those who are responsible for such restrictions. On that note, the EU should closely monitor the role of European companies that enable internet blockages and repression and hold EU individuals equally accountable. The fundamental question of how to build and use technological room for maneuver vis-à-vis authoritarian regimes could be discussed by policymakers, entrepreneurs, and civil society activists in a Europe-wide hackathon.

The EU can achieve most on preserving digital rights and providing access to information when it works together with the United States. Specifically, Brussels and Washington should coordinate to lift sanctions on certain products and services, such as secure communications, that are used by the protesters and to impose restrictions on those that serve the regime, like filtering technologies and spyware.

The protection of individual women’s and human rights defenders should be an additional priority. Because visa and asylum issues are in the hands of EU member states and the EU has no delegation in Iran, it is crucial that member states continue to be present in the country. In addition, EU foreign policy should ensure that EU states can receive politically persecuted people in diplomatic exchanges with the governments of Iran’s neighbors.

Bolster Civil Society Representation

The ongoing revolt underlines the need for the EU to acknowledge—and empower—women as a driving force for social change in Iran. More generally, the demonstrations highlight the importance of diverse participation and the effective inclusion of Iranian civil society voices in all phases of policy formulation toward Iran, based on a structured and long-term exchange of views.

Accordingly, the EU should create processes for a meaningful exchange with Iranian civil society on issues of importance to civic actors in foreign and security policy. It is crucial to acknowledge the difficult but positive and supportive role that the diaspora plays in that regard. It might be necessary to overcome a sense of catering to domestic needs for the purpose of including civil society experts. The aim of a feminist foreign policy is not to listen selectively to civil society voices only when they are needed but to enable civic actors to contribute their priorities independently in an exchange in which they see eye to eye with others.

Align Resources With Gender-Aware Priorities

Along the lines of the above analysis, the EU should identify gender-aware priorities for its funding, reexamine its types of support for Iranian civil society, and mitigate the impacts on civilians of restrictive measures against Iran.

In cooperation with feminist-driven member states, such as France, Germany, Luxembourg, and Spain, as well as partner countries like Canada, the EU should develop mechanisms of joint analysis and instruments to support the people on the ground. For this, it is crucial that EU member states do not close their embassies in Iran but increase their capacities wherever possible. This applies to political reporting and consular issues, such as the processing of visa and asylum applications, for which it may be advisable to build up capacities outside Iran.

EU member states should give special access to women’s and human rights defenders and journalists, for example by establishing a mechanism that enables them to stay in the member state in the short term while continuing their work, for instance in the form of research scholarships. This expertise, in turn, can help the EU high representative for foreign and security policy, jointly with the European Commission and at the request of the EU Council, to draft a comprehensive and well-founded Iran policy.

The EU should consider whether funding to support Iranian civil society can also be used among the diaspora. In the current context, groups outside Iran have gathered evidence on the regime’s persecution while providing direct support to the protesters. More generally, the increasingly repressive domestic environment has led to a massive brain drain, which means that many actors among the recently emigrated diaspora have personal and professional links into the country that they can leverage. Moreover, the EU should examine how much of its available funding for Iranian civil society would be allocated if gender analyses were included in financial decisionmaking, and whether those budget lines can be made available more flexibly given the current urgency.

In the long term, sanctions should be targeted to influence decisionmakers and avoid negative impacts on the people of Iran. The EU must evaluate its restrictive measures regularly from a gender-aware perspective and compensate for them when necessary. For example, the waiver of U.S. sanctions against tech companies is of little use if many Iranians are still unable to pay for the digital services now available because they are barred from international banking due to overcompliance. To that end, EU institutions should provide companies and organizations with clear and easily accessible information on how to navigate the changing sanctions architecture.

A Need for Coherence and Consistency

A feminist foreign policy must be coherent among both the EU institutions and the EU member states. As the feminist approach focuses on the causes of conflict and power dynamics, this requires a critical look at the extent to which EU foreign policy prioritizes human security, gender equality, and women’s and human rights vis-à-vis not only Iran but also neighboring countries, such as Saudi Arabia, other Gulf states, and Egypt. In addition, essential human security concerns can only be addressed regionally. Ultimately, a feminist foreign policy underscores the need for the EU to coordinate its external action both with its member states and with UN measures.

Barbara Mittelhammer is an independent, Berlin-based political analyst and consultant who focuses on human security, gender in peace, and security as well as feminist foreign policy.