Like many island nations in Asia, the Maldives is busy grappling with the best way to advance its economic and national security interests in a region where geopolitical tensions between larger Asia-Pacific nations like China, India, and the United States continue to rise.

Unsurprisingly, views among the country’s political leaders on the best course of action differ. The political debate playing out in the capital of Malé offers a vantage point on the tradeoffs and constraints that policymakers in the Maldives and other similar countries must account for as they strive to protect their national sovereignty.

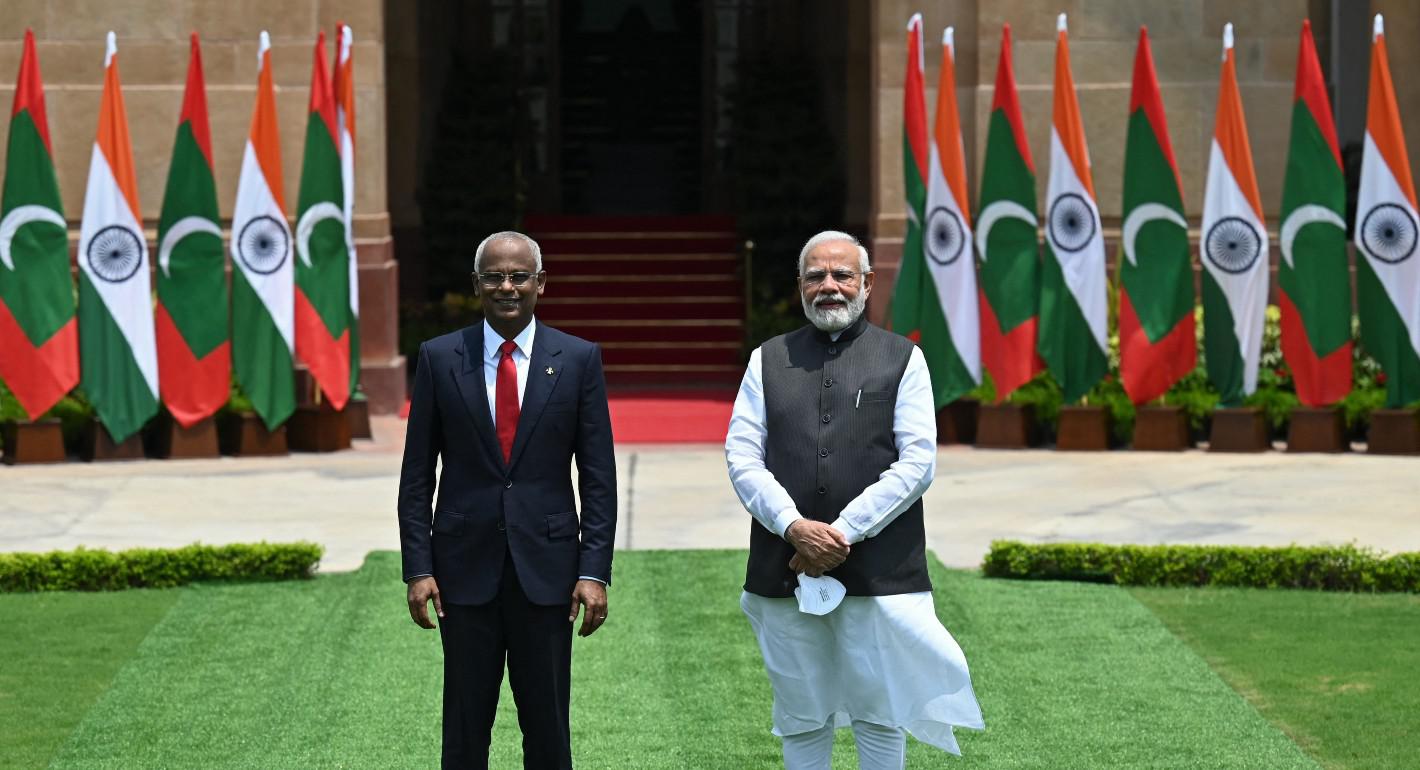

The Maldives’ current government led by President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih has unapologetically oriented the country’s foreign policy toward India as a provider of economic benefits and security. Meanwhile, the country’s political opposition under former president Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom has urged the president to reconsider the closeness of the relationship ostensibly to protect the Maldives’ sovereignty.

The main issue dominating this debate is India’s controversial military presence in the Maldives, though other ad hoc issues have arisen too. While the current government has actively sought to strengthen such ties with India, Yameen and the main opposition force have pressed the government to weaken such ties or even end India’s military presence altogether, as embodied by the slogan “India Out.”

To amplify the India Out campaign’s reach, the opposition has expanded its appeals beyond the capital to outer islands. The expansion of the campaign and the opposition’s heated rhetoric could create a serious rupture in the Maldives-India partnership with potentially significant consequences for both sides.

The Maldives-India Relationship

The strength of the Maldives-India diplomatic relationship has ebbed and flowed based on the ruling party or coalition in power in Malé. For years now, India has been the dominant regional power by virtue of its being the most powerful in the subregion and, more recently, by its Neighborhood First policy. A high priority of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, this core component of India’s foreign policy, which focuses on peaceful relations and collaborative, synergetic co-development with its neighbors, encompasses a diverse range of topics, such as economics, connectivity, technology, research, and education, among others. In response, the Maldives adopted an India First policy, prioritizing its relationship with its larger, more powerful neighbor. As recently as August 2022, Solih reaffirmed the Maldives’ India First policy, with both countries reassuring each other that they continue to remain mindful of the other’s security concerns. He reasserted that India has always been a “reliable ally to the Maldives, through thick and thin.”

This reality persists despite the foothold that China managed to gain in the Maldives’ political scene from 2013 to 2018, when Beijing and Malé struck deals for large infrastructure projects on the islands and inked a free trade agreement. During this period, the Progressive Party of Maldives and its ruling coalition under Yameen (now the country’s opposition force) was in power. The Yameen-led main opposition force consists of a coalition of parties including the Progressive Party of Maldives and the People’s National Congress.

Furthermore, the Maldives relies heavily on trilateral maritime security cooperation with India and Sri Lanka. The purpose of such collaboration is to counter common maritime security threats and challenges such as illicit trafficking; piracy; and illegal, unregulated (or unreported) fishing.1

The three countries cooperate to keep other countries from encroaching on their respective territory. This cooperation is a vital objective given the Maldives’ dependence on the ocean’s bounty for domestic food security and exports (particularly fish and related products). Hence, protecting the Maldives’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is crucial.

In addition to these security ties, the Maldives has been connected to India in cultural, ethnic, and economic terms for centuries. According to anthropologists and other writers, some Maldivians hail from southern India. The origins of Dhivehi (the Maldivian language) harken back to Sanskrit and Pali, which are also the roots of many southern Indian languages. Moreover, Maldivians have long traded with India, listened to Hindi music, and studied in India.

More recently, residents of the Maldives have begun to depend heavily on India for healthcare including a much-appreciated initial supply of 100,000 Covishield vaccines shipped from India in January 2021, near the peak of the pandemic. Furthermore, India has become the main destination for other kinds of medical treatment as well, and the main government-affiliated hospital in the Maldives, the Indira Gandhi Memorial Hospital in the capital, was built with aid from the Indian government. The bilateral relationship has also expanded to the tourism sector. In 2020, India surpassed China and Europe as the leading source of tourists to the Maldives, a crucial development since tourism is the largest sector of the Maldives’ economy and accounts for more than one-quarter of its gross domestic product.

India and the Maldives have also signed a flurry of bilateral agreements in recent years, including $500 million in grants and financing to support maritime connectivity, an $800-million line of credit from the Export-Import Bank of India, and an agreement on exchanging information on the movement of commercial maritime vessels. The relationship especially reached new heights after Solih completed his third visit to India in August 2022.

The opposition has addressed India’s relationship with the Maldives with a range of emotions. Sometimes, its rhetoric is infused with a reflexive nationalistic fervor against the Indian military’s presence in the country. On other occasions, its messaging betrays a highly inflated and adrenaline-filled pessimism that reaches almost paranoid proportions. For instance, critics have referred to the Indian military’s presence as “crimes of this government” that might reduce the Maldives to being “a slave of India” and “losing its independence and sovereignty.”

Regardless of the opposition’s rhetorical approach, its preoccupation with India is driven by suspicion in several domains. For instance, the opposition believes that there has been too little transparency on the terms of the agreements that the Maldives has signed with India. To address this lacuna, it has asked the Parliamentary Committee on National Security Services to disclose the terms of these pacts.

Another target of the opposition’s skepticism is the Maldives’ recently completed new police academy. The project was developed with the Indian government’s assistance and houses the National College of Policing and Law Enforcement. The opposition’s mistrust stems from the sheer size of the building and surrounding complex. One rumor making the rounds implies that the only reason the academy is so large is to house Indians associated with the academy and their families, supposedly rendering it an opportune place to bring more Indians into the country. This conjecture, however, is unfounded.

A third point of contention is Uthuru Thila Falhu, an island that was selected for the development of a dockyard facility and a harbor for the coast guard of the Maldives National Defence Force according to the defense action plan between India and the Maldives. Again, the country’s political opposition is concerned that the presence of Indian technicians and advisers on the island will erode the island nation’s sovereignty.

The opposition has not been content to merely criticize the government; it has also lobbied India directly. In February 2021, a high-level opposition delegation met with the visiting Indian Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar to request his government’s support in maintaining political stability in the Maldives. This manner of outreach by the opposition has sometimes backfired with the Maldivian public. For instance, its meeting with Jaishankar sent confusing signals to ordinary citizens as it appeared to contradict the opposition’s hardline stance on India’s role in the country. As a result, one analyst described this session as a “game of politics” in which the opposition lodged anti-India “accusations in public” while cordially “mingling” with Indian officials “behind closed doors.”

On the one hand, the opposition’s focus on India seems sensible if it wishes to draw the government’s attention to the long-term damage it believes India’s increasing military presence could bring about for the country. Democracy in the Maldives is only fourteen years old as it began with the Constitution of 2008 and the establishment of the multiparty system of government which ended the thirty-year old dictatorship of President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom. Hence, the experience of democracy can be considered as a blink of the eye when compared to the seventy-five years of democratic experience neighboring India has enjoyed. In large measure, the opposition’s fixation on India is premised on the belief that, due either to naivete or inexperience, Maldivian politicians might unknowingly be drawn into a trap.

On the other hand, if the India Out campaign rankles the Indian government, the ones who will suffer are the ordinary Maldivian citizens who rely on India for medical treatment, visas, and economic support. This concern is not idle speculation; the souring of bilateral relations in earlier periods (from 2013 to 2018) during the previous administration had an impact on ordinary citizens. More importantly, if bilateral relations take a dip, who will replace India as the Maldives’ main backer?

On balance, the opposition appears to have concluded that the benefits of the India Out campaign outweigh the costs; it continues to campaign for the removal of India’s military from the country. India’s military presence includes reconnaissance aircraft, military helicopters, and personnel, and it is also believed to include officers of the Research and Analysis Wing, India’s external intelligence agency. The opposition argues that this buildup poses a long-term risk to Maldivian sovereignty.

The Maldivian Government’s Response

The incumbent government’s response to these critiques has, at times, fueled the anti-India campaign rather than tamed it. For instance, the parliamentary group of the governing coalition, led by the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP), submitted a bill to the parliament to ban the “India Out” campaign in February 2022, sparking outrage among the opposition. Government critics called it an “unconstitutional” move tantamount to “suspending” citizens’ ability to convey their discontent, though these critics painted the policy with highly exaggerated expressions like “the illegal stationing of Indian military forces.” It emphasized the gravity of the government’s actions by stating that the attempted ban “marks a dark day in the history of the Maldives as for the first time a sitting president has actively elected to abandon his own people and protect the interests of a foreign military.” It is worth noting that these expressions by the opposition are more for drama and popular appeal. As for the government, although the anti-India campaign created anxiety, state policy or tactics have not changed because the country’s incumbent leaders continue to work closely with India. The India First policy remains intact.

In general, the Maldivian government’s modus operandi in responding to the India Out campaign has been to emphasize the vital importance of its relationship with India and the assistance New Delhi has consistently offered the country. Particularly fresh in the Maldives’ popular memory is India’s aid during the worst of the coronavirus pandemic, when it donated doses of the Covishield vaccine to the islands soon after its rollout in India. The Maldivian government has also reiterated its gratitude to India for allowing Maldivians to travel to India for medical purposes during the pandemic when others were denied entry.

The government of the Maldives has underscored other forms of aid too. It has reminded the public of the assistance India provided in response to earlier crises, like fending off a coup attempt by mercenaries in November 1988, helping with recovery efforts after the major tsunami that struck the Maldives (and many other countries of South and Southeast Asia) in December 2004, and helping address more recent shortages of drinking water. The government maintains that these examples are proof of considerable Indian generosity and good-will. In addition, the Maldivian government has also highlighted India’s role in promoting broader Indian Ocean security especially on the thorny issues of illicit drug trafficking, illegal fishing, transnational organized crime, and terrorism. Each of these issues is important to the Maldives and its security.

Beyond rhetoric, the Maldivian government has also doubled down on its pro-India policies. Despite the opposition’s campaigning, Solih has stuck to his government’s India First policy and has been unapologetic about close ties between the two countries. When India’s Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Radhakrishnan Hari Kumar visited the Maldives in April 2022, Solih noted that “defense cooperation is an integral aspect of the Maldives-India relationship,” and that “military cooperation between the two countries had increased over the past three years.” Reminding Solih of the countries’ numerous joint exercises, maritime safety drills, and patrols in the Maldives’ EEZ, Kumar reportedly reaffirmed India’s continued commitment to the relationship.

The Maldivian government also asserts that the roughly seventy-five Indian military personnel stationed in the Maldives, despite adamant criticism from the opposition, are needed to operate two helicopters and a Dornier fixed-wing aircraft furnished by India. These helicopters are used for humanitarian purposes such as carrying patients from remote islands to regional healthcare centers or the capital’s hospital and conducting search and rescue operations. Furthermore, the government has emphasized that the India-provided military hardware is never used for combat or security purposes. In the absence of Maldivian technical staff to operate the aircraft, the incumbent government has explained, the Indian military needs to have boots on the ground.

Finally, on the contentious issue of Uthuru Thila Falhu, the Maldivian government has clarified that it is simply implementing elements of the defense action plan signed by the previous government in 2016. The minister of defense has also reminded the opposition that it has modified certain clauses to make the Maldivian government the sole administrator of the island with India’s support.

India’s Concerns

No doubt, the India Out campaign has generated substantial concerns for India, the gravest of which is the possibility of violence and harassment against Indian nationals in the Maldives. The opposition in Malé has categorically denied accusations of harassment targeting Indian nationals (such as teachers and doctors) in the country’s outer islands, accusing the incumbent Maldivian government of simply “finding excuses” to bring in more Indians.

Officially, India has expressed concerns about disrespectful public displays of its national flag with “India Out” scribbled on it. However, New Delhi has thus far exercised considerable restrain in its reactions, not wanting to jeopardize its broader strategic aims.

Conclusion

The Maldivian government’s principal concern with the opposition’s India Out mantra is the possible disruption of the country’s wide-ranging relationship with New Delhi. On a practical level, the government worries that just one stray incident of violence against an Indian could halt all medical assistance, food aid, and other bilateral support. It stands to reason that the government is doing whatever it can to counter the campaign.

Thus, the opposition and the government are locked in a battle over India’s involvement in the Maldives, with both sides justifying their position on national security grounds. On the one hand, the opposition strongly feels that the Indian military presence in the Maldives is a threat to the country’s national security and sovereignty. On the other hand, the government repeatedly has asserted that the India Out campaign itself is a threat to the country’s national security as it serves to antagonize the partner country that provides regional security benefits to the island nation.

Both sides have used the legislative process to further their aims. The incumbent government’s proposed bill to stifle the India Out campaign is a case in point. The opposition noted that this move was unveiled without the least bit of irony: the MDP prides itself on advocating free expression, but its bill would do precisely the opposite. In critiquing the government, the opposition submitted a letter to the parliament in April 2022,2 which accused the government and other public entities like the police of narrowing the terms of Article 27 of the 2008 Constitution of the Maldives, which guarantees the right to free expression. The government tried to justify its legislative gambit by saying that its goal was to address the incitement of violence and xenophobia. Eventually, under heavy fire, it shelved the bill.

Contrary to the worst fears about anti-Indian violence, only a handful of minor incidents of harassment against Indians have been reported in the Maldivian press. The opposition has downplayed these reports by calling them “total rubbish” and has emphasized that the goal of the India Out campaign is to compel the Indian military, not Indian civilians, to leave the Maldives.

But the average member of the public may not necessarily understand the nuances of the opposition’s position. In other words, once fierce anti-Indian rhetoric is out there, it can be difficult to predict how disgruntled citizens will act.

Regardless of which party is in power, the Maldives’ official India First policy is unlikely to change. After all, Yameen—despite being the face of the opposition’s India Out campaign—made clear at the signing of the defense action plan with India in April 2016 that New Delhi factors prominently in his estimations of the Maldives’ diplomatic posture as well. To mark the occasion, Gayoom reiterated that the Maldives’ security is linked to India.

At present, the opposition’s singular fixation on India’s security presence has not attracted significant blowback. But if things escalate to an unmanageable level, punctuated by an outbreak of violence against Indians, the opposition—not to mention the government and the ordinary citizens of the Maldives could pay a high price.

This article is part of the Politics of Opposition in South Asia initiative run by Carnegie’s South Asia Program.

Notes

1 Minutes of the National Security Committee of the People’s Majlis (17 February 2022) , published in Dhivehi (Maldivian language) and translated to English by the author.

2 Emergency Submission by Maduvvari Consitituency member Adam Shareef. No. 1631. 25 April 2022. Translated from Dhivehi (Maldivian Language) to English by the author.