Introduction

Approximately 20 million Kenyans are set to go to the polls to exercise their democratic right in the August 9, 2022, general election. As is the case in several countries around the world, technology adoption is regarded in Kenya as an important way of improving the accountability and transparency of electoral processes that have previously been tainted by controversy and mistrust. Kenya has embraced technology in three key electoral processes: voter registration, voter verification, and the transmission of results. Though the adoption of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in Kenya’s electoral process has served to remedy legacy concerns, for instance the lack of updated voter registers, it has also raised new issues, such as privacy matters.

The collection and use of data for canvassing for political support and in digital media for political campaigning in particular brought to the fore the need to protect the right to privacy and ensure a transparent, ethical, and lawful ecosystem when processing personal data. The Data Protection Act (DPA) enacted in 2019 aims to regulate the processing of personal data and empowers citizens to protect their personal data in the electoral process. The combination of improvements to Kenya’s electoral process and privacy protections enshrined in the DPA has yielded real results. Importantly, this reform has also generated crucial, ongoing debates about how to balance efficiency outcomes of technology adoption, public interest in credible elections, and the rights to personal data protection that affect not only Kenya’s upcoming polls but also other African countries navigating technology in the electoral process.

Electoral Laws

Following its disputed 2007 general elections, Kenya formed an Independent Review Commission (also known as the Kriegler Commission), which issued a report calling for the adoption of a biometric registration system to aid in the verification of voters at polling stations. The system would ensure the attainment of the constitutional doctrine of “one person, one vote.” This review found that an estimated 1.2 million deceased voters, at the time of the election, remained on the voter register. The Kriegler Commission report and the promulgation of the Constitution of Kenya, 2010, introduced a number of changes in the electoral processes, including the enactment of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission Act; the Elections Act, 2011; and, subsequently, the Elections (Technology) Regulations, 2017, among other subsidiary legislation.

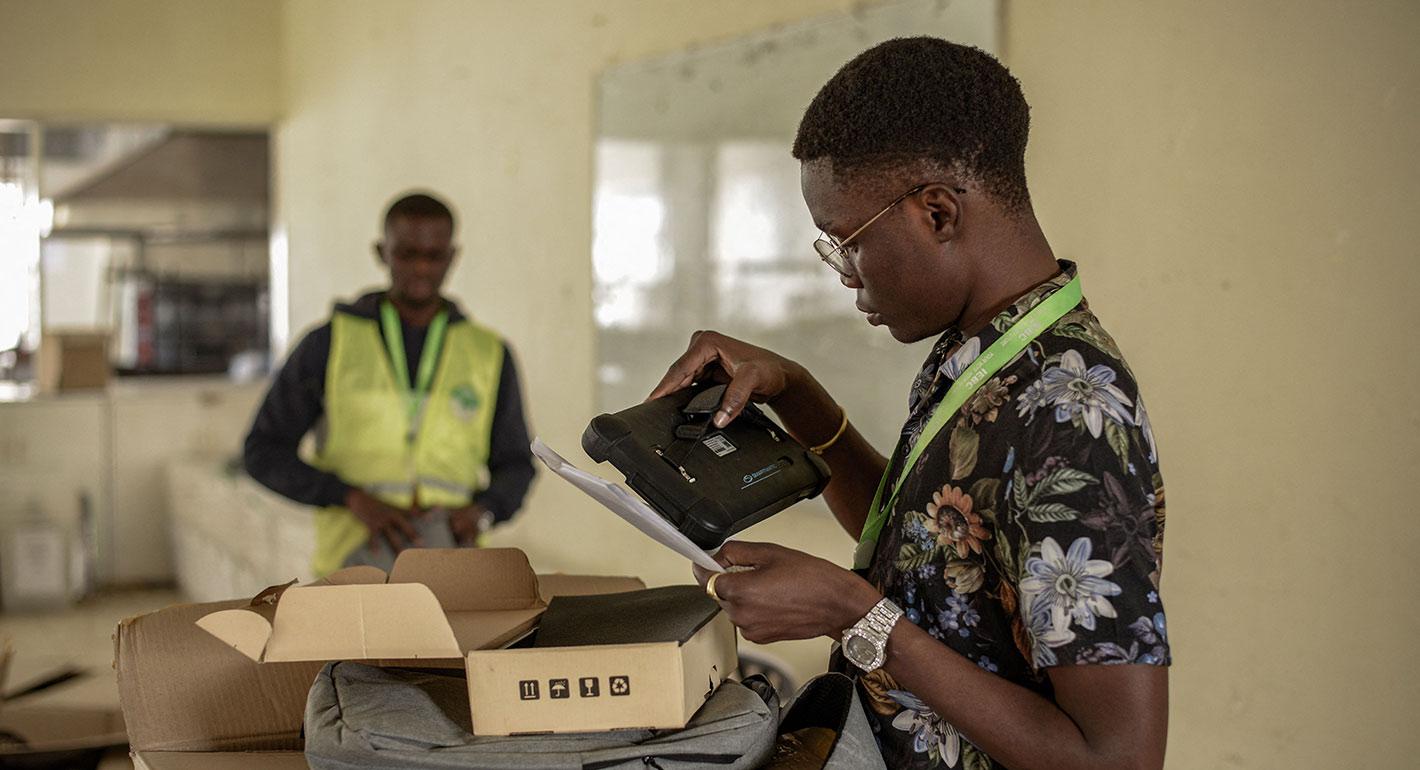

With the enactment of these laws, Kenya became one of fifty-eight countries globally to adopt technology in the electoral process (see figure 1). Across the African continent, twenty-seven countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Gambia, Ghana, Nigeria, and Somalia, have adopted electoral technology in a bid to cure electoral inefficiencies, such as so-called ghost voters, and to promote transparency and fairness. This has enabled the deployment of the Kenya Integrated Electoral Management System (KIEMS), which comprises the Biometric Voter Registration, the Electronic Voter Identification, and the Results Transmission System during tallying in Kenyan elections. The electoral laws mandate the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) to ensure the security of election-related technology. Further, the IEBC is now also required to make the register of voters available “for inspection by members of the public at all times for the purpose of rectifying the particulars therein.”

In addition to the responsibilities of the IEBC, there is a parallel process of collecting potential voter data by way of political party member registers under the Political Parties Act. Political parties are required to register their members and submit a list of the names, addresses, and identification particulars of all such members to the Registrar of Political Parties. Additionally, the same act also requires that the Registrar of Political Parties “verify and make publicly available the list of all members of political parties.”

Application of the DPA in the Electoral Process

The DPA is the overarching legislation on data protection in Kenya and was lauded as an apt tool to address violations of individuals’ rights to privacy that were prevalent in the 2013 and 2017 Kenyan general elections. The DPA enhances the integrity of elections and democracy by safeguarding the collection and processing of all personal data involved in electoral processes. This includes voter registration, inspection of the Register of Voters, recruitment of members by political parties, and political campaigning, all of which must be undertaken in accordance with the provisions of the DPA. The collection and processing of personal data on voters (or potential voters) by all stakeholders engaged in the election process must be limited to the legitimate-purpose requirements and reflect at all stages of the processing a fair balance between all interests concerned and the rights and freedoms of the electorate. The DPA further sets out obligations for entities processing personal data for electoral purposes, including the localization of this data in Kenya.

The DPA impacted the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission Act by way of a consequential amendment that now requires that the “principles of personal data protection set out in the Data Protection Act apply to the processing of personal data of voters.” Although the DPA did not make any other consequential amendments to existing electoral legislation, it calls for a balance between the rights of the electorate to data protection and the public interest in ensuring the effective operation of the entire electoral process.

The Kenyan electoral laws require the publication of registers as a means to increase transparency in the electoral process and prevent situations where deceased voters supposedly cast votes. Prior to the enactment of the DPA, access to the complete voter register could be easily obtained through an Access to Information request. This practice now requires all entities handling data for electoral purposes to consider the data protection principle of purpose limitation and data minimization and to reveal only the information that is necessary to achieve the requested purpose, rather than releasing the entire voter register. Kenya’s DPA has remedied some of the issues that existed in previous years, which are discussed in turn below; however, there is still a lot of progress to be made to fully realize the benefits of compliance.

Addressing Transparency Concerns

The disputed 2017 Kenyan elections resulted in a nullification of the presidential results following, among other matters, a lack of transparency in the process. The use of technology and operationalization of the KIEMS for registration and identification of voters and the transmission of results was intended to ensure the verifiability, transparency, security, and accuracy of elections and the electoral process (see figure 2). However, in Presidential Petition No. 1 of 2017, it was argued that there were significant discrepancies caused by the delay in transmission of results from some polling stations; irregularities in the prescribed electoral forms submitted; failure to provide access to system logs for verification of results; and the failure of systems’ security in hosting primary and disaster recovery sites locally. The Supreme Court of Kenya determined that the discrepancies arising from the lack of transparency were sufficient to nullify the elections and call for fresh presidential elections to be conducted in accordance with the electoral laws.

The DPA and the recently passed Data Protection (General) Regulations call for the processing of personal data for the strategic purpose of conducting elections through a data center or servers located in Kenya or the retaining of a serving copy within the jurisdiction. This position aligns with the data protection principle of availability, which was incidentally promoted by the Supreme Court in its decision in the 2017 presidential election petition. In a press statement in December 2021, the IEBC confirmed that it had acquired and established local data centers. This development may serve to remedy the lack of transparency and availability challenges that were raised in the 2017 presidential petition and ensures that the electoral body is in compliance with the DPA.

Use of Personal Data for Digital Political Campaigns

The use of personal data is crucial for effective political campaigns. The 2017 elections saw a surge in the access and use of personal data for political campaigning, including both bulk SMS texting that was targeted at particular constituents and unsolicited messaging seeking votes. These elections also witnessed the emergence of the infamous methods used by the company Cambridge Analytica, which developed microtargeting strategies and was allegedly itself involved in microtargeting through social media platforms.

Digital media is an effective, cheap, and targeted tool to reach the electorate. During the 2017 elections, the use of SMS and social media by political parties and political aspirants was largely governed by the official guidelines on bulk messaging and social media communications. Although these guidelines addressed matters of transparency by requiring identification of the political party or individual sender, the regulation of these messages was primarily to counter hate speech and incitement of violence and did not address matters of consent to data use.

Digital political campaigning is still a present-day issue leading up to the 2022 election. However, telecommunications service providers and social media platforms have become more conscious of the misuse of technology and prevalence of misinformation and disinformation in political campaigning. This shift in consciousness is visible from the efforts that entities such as Meta are taking to prepare for the upcoming Kenyan elections by setting up election operation centers, establishing procedures to verify information and remove harmful content, and creating transparency with political ads by adding sponsorship information. This is a big step forward, as a recent report showed that most Kenyans receive political news through social media platforms.

It is important to note that the regulation of telecommunications providers and the criminalization of fake news is established under the Kenya Information and Communications Act and the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, respectively. However, the use of personal data without the express consent of individuals has shown only a slow decline by data handlers required to obtain consent under DPA. This may be attributable to the novelty of Kenya’s DPA and a limited understanding of the obligations under the law by data handlers.

Voter Registration and Verification

In June 2021, the Office of the Registrar of Political Parties (ORPP) and the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner received numerous complaints on the registration of citizens as members of certain political parties without the citizens’ consent. This came to light after the ORPP’s move to adopt a technological solution, the Integrated Political Parties Management System (IPPMS), for verification of party membership, a program that was said to offer a practical and efficient solution for handling huge submissions to the party membership register. This solution, which was piloted in mid-2021, is housed on the eCitizen platform and has digitized the already existing member registers for ease of membership management.

The platform exposed thousands of unauthorized registrations of political party members and gave the public an opportunity to opt out of political membership registration, which would help the public registers become a near-true reflection of political parties’ member registers. This position would previously not have been possible with manual registers that were submitted to the ORPP and manually published for verification. The use of technology pushed conversations with the data protection regulator and resulted in the publication of a Guidance Note on the Processing of Personal Data for Electoral Purposes, which is geared to guide compliance with the DPA by electoral players, including political parties.

The IEBC and ORPP have both adopted technology for register verification. The eCitizen ORPP portal allows any member of the general public to verify their registration to a political party or opt out in the face of incorrect registration. Similarly, the IEBC is using SMS and its online portal, alongside manual processes, for the verification of the voter register. This enables voters to ensure their personal data is adequately captured. However, the sole use of technology, particularly on the member register, may make verification or opting out available only to those who have access to technology, limiting the rights of individuals without the requisite capacity or know-how to access the electronically managed registers.

Conclusion

The impact of the DPA on electoral processes in Kenya continues to be felt ahead of the 2022 elections. It is understood that electoral processes must, as much as possible, align to the DPA. However, in the run-up to the 2022 elections, it is increasingly apparent that a guidance note is not sufficient, and a harmonization of legislation is required. The need to balance competing rights of parties involved in the electoral process and the decision on which competing right takes precedence remain largely unanswered. The electoral laws and data protection laws fail to give sufficient clarity on what considerations are to be given when balancing these competing rights. Perhaps this is a question to be answered by judicial determination.

As the data protection authority continues to establish itself and the public gains greater awareness and understanding of the body and the act, the DPA may have a larger impact in subsequent elections, including in adequate implementation of data protection principles. Further, the body of knowledge of the interaction between data protection and elections in the African context may see a marked increase with the recent enactment of data protection laws in many African nations.

Rose Mosero is the deputy data commissioner–compliance at the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner. She previously served as the legal, policy, and regulatory advisor to the Cabinet Secretary for Kenya’s Ministry of ICT, Innovation and Youth Affairs. She also served as a member of the taskforce that developed the recently promulgated data protection regulations and was involved in the development of the Data Protection Act, 2019. She is a fellow of Information Privacy conferred by the International Association of Privacy Professionals, where she sits on the Publications Advisory Board.

This piece reflects the personal opinions of the author and does not represent an official statement from the office she holds.

.jpg)