Summary

The European Union (EU) has a growing interest in investing in the Global South as the bloc seeks to fill a niche amid the geopolitical rivalry between the United States and China, find new allies in support of multilateralism, and diversify its international relations in pursuit of its norms and interests. But the union’s policies and ambitions are underinformed by empirical research on how the Global South views the EU and Europe as a whole.

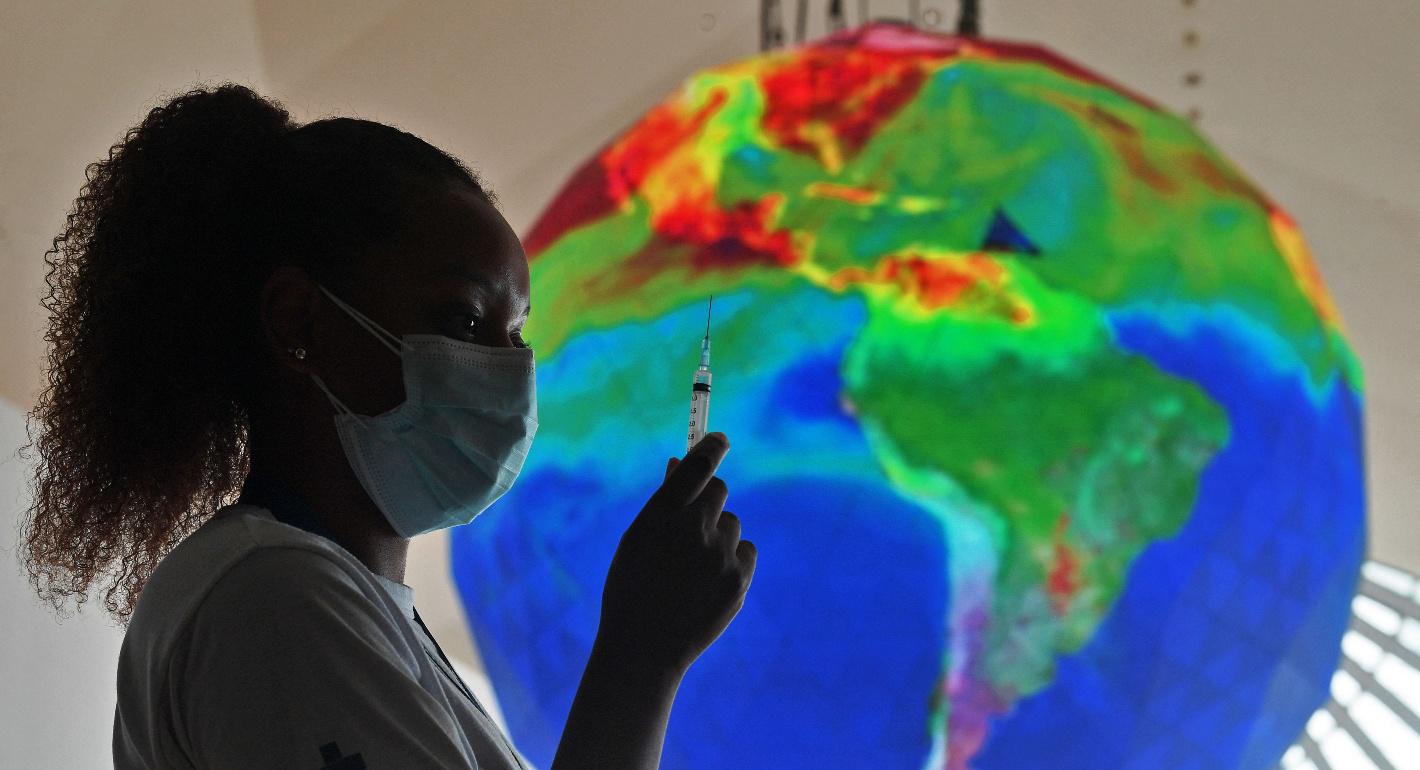

This paper presents the initial results of an eighteen-month-long project conducted by Carnegie Europe and the Open Society European Policy Institute (OSEPI) that explored perspectives on Europe’s international role through the eyes of the Global South.1 The project was launched in 2020 and, by necessity, the coronavirus pandemic and the world’s responses to it became the backdrop for identifying and deconstructing the key issues and dilemmas in the relationship between the EU and the Global South. What followed were some sobering lessons that offer new ways of thinking about future engagement.

After two years of battling the coronavirus, and as domestic restrictions ease in much of the Global North, what has emerged is a widening gap between North and South. Without the resources and policy innovations the West used to shield itself from the worst of the pandemic’s economic effects, developing countries, already economically vulnerable, were hit hard by the crisis. In some countries, this has reversed decades of progress on poverty, healthcare, and education.

The pandemic could have been a watershed moment: an opportunity for the EU to reframe donor-recipient relations, build on ongoing efforts to eliminate global poverty, and demonstrate the value of multilateralism. Yet, rather than capitalizing on the chance to strengthen the Global South’s resilience, the EU was perceived as pursuing more insular strategies, from hoarding COVID-19 vaccinations to opposing vaccine waivers. While outwardly espousing the benefits of international solidarity, the EU was unable to enact extensive policies to address the structural economic and political imbalances in its relationship with the Global South. This shortsightedness led to several missed opportunities for the EU to play a leading role in helping the Global South navigate what will be a long and painful recovery from the pandemic.

At the same time, geopolitical games among the United States, Europe, China, and Russia tarnished the West’s image, leading to further resentment and frustration. The EU’s efforts to deweaponize access to healthcare by exporting half the vaccines it produced and supporting the establishment of the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) initiative in the early days of the pandemic were admirable; but a series of missteps—by accident or design—seriously dented the EU’s credibility in the eyes of many of its partners. Much of this harm can be attributed to a strategy that tried to balance competing and contradictory aims with a values-based external policy that boasted the principles of solidarity at its core. China and Russia exploited this weakness to position themselves as more reliable partners than their Western counterparts.

However, there are still opportunities for the EU to regain what it has lost. Both Africa and Asia have turned to multilateralism to effectively combat the coronavirus. The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (ACDC) has played a leading role in coordinating African responses to the pandemic, while the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has announced the creation of the Center for Public Health Emergencies and Emerging Diseases. The EU can support these organizations in a bid to deepen partnerships with the Global South.

The coming year is rife with opportunities to enact course correction: patent waivers will be discussed in the World Trade Organization (WTO), while Indonesia’s 2022 presidency of the Group of Twenty (G20) and the EU’s Global Gateway initiative are chances for Europe to recharacterize its relationship with the Global South. The EU must embrace ambitious and creative forms of cooperation to build lasting alliances that will, in turn, address global inequality in a manner that aligns with the union’s declared intention to create more equal partnerships in the global community.

Introduction

It is a truism that the coronavirus knows no borders, making the pandemic of the past two years a truly global phenomenon. But the crisis has shaken the world in different ways in different places, and one result is an increasing asymmetry between the Global North and the Global South.

In the developed North, the epicenter of several outbreaks and waves of the virus, governments mobilized extraordinary measures, money, and science to beat it. Unprecedented policies to support society and a uniquely cooperative international scientific community together found ways to curb the ongoing devastation of the virus. In the Global South, past pandemics may have made some countries and peoples in parts of Africa and Asia more resilient in dealing with outbreaks, but that experience did not help them face the impacts of the coronavirus on the Global South’s recovery prospects or own the solutions to the crisis. The pandemic has affected education, migration opportunities, manufacturing, and trade, with likely long-term consequences. The ways in which the global crisis was handled has underscored the gap between the shaping power of the United States, Europe, China, and Russia, on the one hand, and the path dependence of the rest of the world, on the other.

The European Union (EU) seized on the coronavirus pandemic to push an ambitious path of reform with a strong emphasis on green and digital transitions, potentially giving a new impetus and direction to European integration. But this innovation was largely confined to the union’s borders.

Laudably, especially given the crisis context of the first months of 2020, the EU did not omit to set aside resources to support the rest of the world to deal with the impacts of the coronavirus. But while embracing a narrative of international solidarity, the union failed to use the opportunity to address some of the structural economic and political imbalances in its relationship with the Global South. These include income and income-distribution differentials and a dysfunctional foreign debt system; blocks to the delivery of goods and services, including trade barriers; differences in health and education systems, know-how, and research and development (R&D); ongoing competition for access to the Global South’s resources and raw materials; and deeply felt historical grievances and a lack of trust.

Disregarding the lessons of past pandemics, notably in Africa and Asia, the Global North made insufficient efforts to tackle structural reform of the international system of health services, distribution, and production capacity. Vaccine distribution continues to be vastly unequal, while debt relief and economic support for lower-income countries remain negligible. Changes to World Trade Organization (WTO) rules on patents and permits, which would have increased the capacity to produce vaccines, did not happen because of opposition from the EU, particularly Germany.

At a time when the EU seeks modes of engagement with the rest of the world based on principles of equal partnership, this was a missed opportunity to rethink donor-recipient relations. That failure highlights yet again the inconsistencies between European internal and external policies and contributes to deepening inequalities between North and South. Ultimately, this state of affairs leaves countries vulnerable to intensifying geopolitical rivalry and increasingly weaponized health policies.

The View From the Global South

The recognition in the Global South of the EU’s efforts to provide financial and technical support to the developing world went hand in hand with an underlying suspicion that the unprecedented mobilization was motivated primarily by the pandemic’s impact on the Global North. Africa and Asia have experienced previous outbreaks of infectious diseases, none of which has come close to receiving the scale of attention seen in the global response to the coronavirus pandemic. As African governments, for example, redirected EU aid and attention toward the new priority, many were left wondering whether COVID-19 is as deadly as the many other diseases that afflict Africa, from malaria to cholera to tuberculosis. These diseases have significantly more sobering consequences for African populations than does COVID-19, but past efforts to combat them are yet to yield sustainable results.

From the Global South’s perspective, geopolitical competition was already the dominant lens for reading world politics before the pandemic struck. Confrontation among the West, China, and Russia has played into domestic political dynamics, shortening the distance between global and local politics. The coronavirus pandemic has magnified this trend, confirming the Global South as a critical site for geopolitical competition, where vaccine diplomacy and debt relief have politicized health policies.

Debates in the developing world show that geopolitical dynamics shaped perceptions of international action on the pandemic. Chinese and Russian vaccine diplomacy received ample space in the media, especially in Asia and Latin America, while a current of mistrust ran through attitudes toward Europe and the United States. Anticolonialist sentiments popped up; in Africa, the term “coronialism” was coined in reference to the fact that COVID-19 infections spread to Africa from Europe.2

The West’s vaccine hoarding was accompanied by suspicions that exported or donated vaccines were faulty leftovers unwanted by European and American citizens. That was the case especially in spring 2021, when governments were bickering over the AstraZeneca vaccine—the only shot that was sold at the cost of production.

In countries with histories of colonialism and unethical medical practices, doubts and mistrust in vaccines abounded, slowing the vaccination rollout.3 Safety concerns were so persistent that in South Africa, for example, health officials stopped giving the Johnson & Johnson shot two months after dropping the AstraZeneca vaccine.4 In addition, long-standing structural inequalities linked to poverty hindered the vaccine rollout because of a lack of adequate infrastructure, part of the reason for which 1.7 million AstraZeneca doses went unused in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in early 2021.5 In Asia, the inability of many Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries to procure the highly prized Western-manufactured Moderna and Pfizer vaccines in early 2021 meant strong recourse to the Chinese Sinopharm and Sinovac jabs.

China and Russia exploited these suspicions of Europe and America to gain influence in the developing world. Both Beijing and Moscow launched aggressive vaccine diplomacy campaigns under the banner of South-South cooperation, arguing that humanitarian imperatives and global public goods could be better addressed by centralized governance models.6 To counter doubts in the Chinese and Russian vaccines, Beijing and Moscow sowed distrust in the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), accusing Western countries of politicizing the market authorization of medicines.7

The story of Brazil’s vaccine procurement is the most illustrative example of the way in which the struggle against the coronavirus could be turned into a competition for influence. When the country was struck by a deadly wave of COVID-19, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro—a staunch supporter of former U.S. president Donald Trump and a hawk toward China—was forced to review his opposition to Huawei’s fifth-generation technology (5G) investments to strike a deal to procure Chinese vaccines. Elsewhere in Latin America, China’s millions of dollars’ worth of donations meant that Beijing became Venezuela’s largest donor (followed by Russia) and led some to describe China as “the savior of Venezuela.”8

The massive investment in vaccine diplomacy may not eventually pay off. The lower effectiveness of Chinese vaccines, coupled with the fact that Chinese and Russian jabs are not recognized by certain health agencies or governments, has tarnished their attractiveness according to some reports.9 Yet, this does not translate automatically into more trust in Europe and the United States. Some in the Global South saw the transatlantic partners as playing geopolitics as much as China and Russia: in the words of one observer in Indonesia, Group of Seven (G7) leaders were “using ‘multilateralism’ and ‘science’ but actually aiming to further their political and military presence in the Asia-Pacific region with a single mission: to contain China.”10 Banning anyone who had received a vaccine not recognized by the EMA—that is, a Chinese or Russian one—from traveling to certain European countries reinforced the perception of a walled and privileged community.

Health as a Global Public Good? COVAX, the EU, and the Limits of Global Governance

Despite the nationalist and protectionist reactions that dominated the first weeks of the pandemic, the EU was able to coordinate its responses both internally and externally—a considerable feat in itself. Internally, member states agreed to a degree of coordination and gave the European Commission unprecedented tasks, for instance in vaccine procurement and the coordination of a vaccination passport, in an area that is of national, not EU competence. Externally, the union developed a narrative and crisis-response initiative known as Team Europe, framed in terms of international solidarity. Team Europe consists of the EU, the EU member states, the European Investment Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Since its launch in April 2020 as part of the EU’s global response to the pandemic, Team Europe’s concept has been incorporated into the approach of working better together to further improve the coherence and coordination of efforts, notably with partner countries.11

Unlike the United Kingdom and the United States, which in the early phases of the vaccine rollout focused exclusively on domestic vaccinations, the EU continued to export half the vaccines it produced, although it did so quietly to avoid a public nationalist backlash at home. So quietly, in fact, that in a 2022 assessment among ASEAN countries of global partners’ vaccine support, the EU received a 2.6 percent positive perception score, compared with China’s 57.8 percent and the United States’ 23.2 percent.12 Yet, the EU has also championed the establishment of the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) initiative and the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator, mechanisms to ensure equitable global access to coronavirus vaccines, tests, and treatments and to strengthen health systems. Finally, the EU pledged 500 million doses and committed nearly €150 million ($165 million) in humanitarian aid to support the vaccination rollout around the world.13

Despite these efforts, the gap between pledges and delivery remains painfully wide. While COVAX has provided some 1 billion vaccines to 144 countries, this represents only one-tenth of what is needed.14 And in stark contrast to the high rates of fully vaccinated people in the world’s most developed countries, only 10.6 percent of people in low-income countries have received one dose, and just 5.5 percent have had two doses (see figure 1).15 In the words of John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (ACDC), “COVAX has been a moral tragedy. The intent and the design [were] perfect, excellent, but the execution—even the people running COVAX will admit that it has not delivered on its promise.”16

In June 2021, the heads of international economic and health organizations urged world leaders to rapidly finance a new $50 billion global road map to accelerate the equitable distribution of health—an investment expected to yield returns to the tune of $9 trillion in economic growth by 2025.17 By November 2021, of the pledges made by the United States, the EU, and the United Kingdom, only 15 percent, 12.5 percent, and 6 percent, respectively, had been delivered.18

Considering that combined, Africa and Asia make up three-quarters of the global population, they account for just 30 percent of the global coronavirus caseload (see figure 2). Part of this seemingly mitigated situation can be explained by underreporting and demographics, but the other side of the story is these regions’ experiences of fighting epidemics. Asia had to contend with the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, followed in 2009 by an outbreak of the H1N1 influenza virus, commonly called swine flu. In Africa, the Ebola crisis that struck West Africa in 2013–2014 led to the 2016 creation of the ACDC, a specialized technical institution of the African Union (AU) that works to strengthen the capacity of African nations to respond to disease threats and has been instrumental in coordinating African responses to the coronavirus.19 Asia has taken concrete steps in emulating the ACDC and in December 2020 announced the creation of the ASEAN Center for Public Health Emergencies and Emerging Diseases.20 South America has no equivalent body and, by contrast, accounts for over 30 percent of coronavirus deaths worldwide.21

The African and Asian experiences speak volumes about the long-term structural lessons that could have been implemented in response to the coronavirus pandemic, from increasing public health capital to shoring up domestic and regional manufacturing and supply-chain capabilities.22 Yet, more than two years into the pandemic, the Global North continues to resist taking on board the hard lessons of the past decade. As former British prime minister Gordon Brown wrote in late 2021 as South Africa shared evidence of the spread of the new Omicron variant, “our failure to put vaccines into the arms of people in the developing world is now coming back to haunt us.”23 The EU did not go far enough in limiting the monopolization of vaccine access, imposed a travel ban after South Africa’s disclosure of the emergence of the Omicron variant, and opposed a temporary intellectual property waiver for COVID-19 treatments.

Aside from inequities in vaccine distribution, public and private stakeholders are examining patent waivers, technology transfers, and public licensing to address gaps in production. The United States and the EU have created a joint task force to examine vaccine supply chains and manufacturing.24 Yet, progress has been hindered by differences between Washington and Brussels on patent waivers. The EU and the United Kingdom, which are among the funders of the COVAX mechanism, have blocked initiatives to waive WTO obligations to patent-protect medicines, vaccines, and diagnostics—a move that has pushed up the prices of pharmaceuticals and made it harder for lower-income countries to buy them. Secrecy also surrounds the allocation of resources for R&D as well as the rules attached to public funding for R&D, the scheduling of deliveries, and the conditions for selling or donating excess vaccine doses. Essentially, the EU’s solidarity approach has been undermined by allowing COVAX to work within the paradigm of safeguarding patent rights.25

Yet, protecting patent rights tells only part of the story, because there is a kaleidoscope of other issues that need to be addressed. Manufacturing vaccines also requires hard technology, specific knowledge, data from clinical trials, market-entry permissions, and access to primary materials. These details are not included in intellectual property waivers, so there needs to be a whole-of-sector approach that considers the different facets that prevent a global overview of the mismatch between supply and demand.26

In August 2021, the WHO started building the first global vaccine-manufacturing hub together with the South African government and the Cape Town–based biotech company Afrigen, but Moderna and Pfizer did not consent to sharing their acquired knowledge.27 Although Africa consumes approximately one-quarter of the world’s vaccines, it manufactures less than 1 percent of its routine jabs, leaving Africans exposed to supply-chain and public health risks.28 Yet, forcing multinationals to share their licenses will take time and be of limited use if the full range of issues is not addressed.

Efforts could be better focused on financing vaccines in least developed countries and ensuring that shots are well used. However, it was only in November 2021 that European Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis admitted the possibility of targeted waivers on compulsory licenses, which would allow the production of cheaper vaccines.29 The EU’s timid overtures fall short of demands from India and South Africa to lift intellectual property protections for three years and contrast with U.S. support for a full waiver of intellectual property rights.30 These events have exposed the inconsistencies of the solidarity narrative of the EU’s global response.

Build Back Better?

The contrast between what was achieved in the Global North to combat the pandemic and how those achievements affected the Global South is repeated in economic policies and prospects. In Europe in 2020, the economic shock of the pandemic triggered an unprecedented mobilization of public finances and resources to save the economy and prevent a major recession. Long- and deeply held assumptions about austerity and neoliberalism were challenged. Back in 2008, the global financial crisis had already exposed the fragility of the EU’s economic governance and the inequalities among its member states. Despite many calls for reform and the deep political fractures caused by the eurozone crisis, the long impact of the 2008 financial crisis did not trigger a governance reform of the eurozone. It took the coronavirus pandemic to challenge the EU’s economic model.31

Unlike the top-down interventions of 2008, the scale of the response in 2020 required a different social bargain to ensure buy-in from European publics. The EU’s total post-coronavirus recovery package includes temporary waivers on state aid rules, a European Central Bank emergency purchasing fund, public financing of research into vaccines and therapies, public vaccine procurement, and national measures to soften the socioeconomic impact of lockdowns, such as furlough schemes, unemployment benefits, and support for small businesses.32 After years of austerity and fiscal prudence, the €750 billion ($830 billion) package agreed on in summer 2020 was one of “reformist experimentation” in the words of historian Adam Tooze, with a new goal to build back better through a green and digital transformation of the economy, supported by public investment.33

Meanwhile, the picture is less optimistic for the Global South. The economic impact of the pandemic on a large part of the world outside Europe and the United States was devastating. In 2020, the lowest-income countries lost $150 billion, roughly the equivalent of the previous year’s worldwide development assistance.34 The external shocks included sharp contractions in real exports, lower export prices, and reduced remittances and tourism receipts. The ability of governments to mobilize fiscal responses varied enormously: according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), by October 2020 advanced economies could spend the equivalent of over 8 percent of their gross domestic product (GDP) to counter the impact of the pandemic, whereas low-income countries could spend only 2 percent (see figure 3).

The pandemic has exacerbated earlier vulnerabilities. Today, nearly half of emerging-market and developing economies and some middle-income countries risk falling farther behind, undoing much of the progress made in eradicating extreme poverty and meeting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Inequalities are rising within and between countries. One proxy measure that contrasts the North’s and South’s future prospects is encapsulated in education: children in the poorest countries lost an average of nearly seventy days of school in 2020; in emerging-market economies the figure was forty-five days, whereas in advanced economies it was just fifteen days.35

Whether and how the extraordinary debt-relief measures promoted by the IMF will manage to address this asymmetry remains to be seen.36 For its part, the EU has disbursed its commitments, specifically €170 million ($187 million) to the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust, an IMF facility that provides grants for debt relief to the poorest and most vulnerable countries exposed to natural or public health disasters.37 Yet, the EU has failed to move out of the donor-recipient model of international solidarity. For instance, European countries did not extend bold fiscal measures to support African countries and respond to a global campaign aimed at redesigning the economic architecture that underpins international lending, borrowing, and debt servicing.38

Indeed, the pandemic has only reinforced cynicism over the perceived hypocrisy of the EU’s so-called values-based foreign policy, and the union’s global image has suffered in regions where it has key trade and economic interests. In Asia, for example, the EU is no longer seen as the champion of a rules-based international order, with trust dropping from 32.6 percent in 2021 to 16.6 percent in 2022—just slightly ahead of China.39

Missed Opportunities

When the coronavirus struck, the writing was on the wall. Forecasts about the frequency, impact, and global nature of pandemics were known. So far, the effect of the pandemic has been to accentuate asymmetries between North and South. For all the talk about the need for a global recovery, governments in the Global North have been as unambitious with respect to their global policies as they have been ambitious in their own recovery strategies.

For the EU, the pandemic has represented a series of missed opportunities. The COVAX mechanism and Team Europe efforts could have led to the development of a new paradigm in which coronavirus vaccines were understood and treated as a common good and emergency responses and vaccine distribution were matched with efforts to share out manufacturing capacity and regulate the profits of pharmaceutical industries.

Instead, by blocking the decentralization of production and protecting the interests of manufacturers located in the Global North, the EU is contributing to the widening gap between rich and poor. Politically, this is a boomerang for the EU: not only was this a missed opportunity to reform the donor-recipient paradigm, but it also represented a setback after the achievements of the past decade in eradicating absolute poverty. The EU’s approach has dealt a blow to the credibility of the union’s solidarity principles in its foreign policy.

The coronavirus crisis has not yet led to discussions about reforming international organizations, and the opportunity was not seized to rethink their role and the transparency of their practices, especially in the processes of vaccine production and distribution. Indeed, despite efforts by the EU to address these challenges, such as a call from some member states for the IMF to improve financial assistance to vulnerable countries or the European Commission’s Global Gateway investment initiative, there has been a lack of appreciation of the pandemic’s long-term implications on trade and investment patterns. This includes impacts on global supply chains, re- and onshoring, and the rebound of stifling protectionist measures that could further hobble economic recovery in the Global South.

The November 2021 Asia-Europe Meeting promised to strengthen multilateralism for shared growth. But beyond a nod to the “significant financing needs and debt vulnerabilities in many low- and middle-income countries” and an acknowledgment that public financing is needed to shore up the private sector, which will be key to the recovery, concrete results have been underwhelming.40

Governments across the Global South are increasingly feeling the pressure to spend more to protect their most vulnerable. Yet, the mechanisms available to them to do so are sorely wanting. Despite best intentions, many of these Northern-driven mechanisms, like debt relief, are increasingly perceived by their Southern recipients as insufficient or inaccessible because of the long laundry list of requirements needed to access them—or else as delaying tactics, because they postpone the inevitable and painful pay-up day.

It is not too late to reimagine the role of international organizations and the shape of international practices. The AU, for example, is designing a continental pathway for addressing health security that provides an agenda for international donors to align with.41 At the February 2022 EU-Africa summit, the AU presented clear and strong demands to EU partners on economic recovery and health distribution. So far, only France, Italy, and Spain have agreed to recycle 20 percent of their IMF special drawing rights—an international reserve asset that supplements members’ official reserves—to Africa. Patent waivers will be discussed in the WTO in spring 2022. Indonesia’s 2022 presidency of the G20 is another opportune moment to build momentum toward more relevant support initiatives that go beyond technical approaches.

Increasing such support would also require greater efforts at coordination among the countries that have vaccine capacity. The coronavirus pandemic has accentuated the rivalry among the West, China, and Russia, but the West itself has also dealt with the crisis in an uncoordinated way. During the first year of the pandemic, transatlantic discord took a heavy toll on strategy alignment.42 But cooperation has been found wanting even during the administration of U.S. President Joe Biden, with differences in export and vaccine policies and WTO rules having major impacts. At a time when transatlantic cooperation is enjoying a new honeymoon, the modesty of collaboration on global health among the richest parts of the world is a glaring stain.

The West’s absence is all the more remarkable given the accentuated geopolitical rivalry and the primacy that the United States attributes to countering China’s rise. Beijing has exploited the pandemic to the maximum to cast itself as a donor of vaccines and medical equipment to boost its presence and influence across the Global South. The retreat of the United States, in particular, and the EU’s lackluster performance have given China and Russia free rein to consolidate their influence and intervene in conflicts across the Global South, such as in Ethiopia and Venezuela.

Conversely, working cooperatively with partners across the Global South could have provided opportunities to deepen partnerships and expand networks of like-minded countries, at least when it comes to deweaponizing access to health. With more ambition, affirming new and innovative forms of cooperation can be a chance to build lasting alliances in favor of multilateralism. This requires addressing global inequalities.

Finally, Europe missed the opportunity to use the pandemic to give credence to its stated intentions to build more equal partnerships with countries across the globe. Mistrust toward the goals of EU engagement and historical grievances that, in some cases, are rooted in the experience of colonialism have tainted the relationship between Europe and the Global South. The Global South’s growing salience in international politics, calls to reform relations between Europe and the rest of the world, and the need to reshape the international order in light of increased geopolitical rivalry all warrant a more ambitious and global response.

About the Authors

Rosa Balfour is director of Carnegie Europe. Her fields of expertise include European politics, institutions, and foreign and security policy. She is also a member of the steering committee of Women in International Security Brussels and an associate fellow at LSE IDEAS.

Lizza Bomassi is the deputy director of Carnegie Europe, where she is responsible for harmonizing Carnegie Europe’s strategic and operational priorities and managing relations with Carnegie’s global centers and programs as well as partner organizations in Europe.

Marta Martinelli is senior director of programs at the Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC). She co-led the work undertaken in this project as head of external policies at the Open Society European Policy Institute (OSEPI).

Carnegie Europe is grateful to OSEPI for its support of this project.

Notes

1 This paper partly draws on insights gathered through the research project The Southern Mirror, which examines perceptions of Europe from seven countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. The authors are grateful to the researchers involved in the project and to Alice Vervaeke, Caroline Klaff, Cyrine Drissi, and Pavi Prakash Nair for their research support.

2 Amy S. Patterson and Emmanuel Balogun, “African Responses to COVID-19: The Reckoning of Agency?,” African Studies Review 64, no. 1 (March 2021): 144–167, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/african-studies-review/article/african-responses-to-covid19-the-reckoning-of-agency/7891A1C068A28D7C7B08EB6AFACBDBAF.

3 Mariam O. Fofana, “Decolonising Global Health in the Time of COVID-19,” Global Public Health 16, no. 8–9 (August–September 2021): 1155, https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1864754.

4 Benjamin Mueller, “Western Warnings Tarnish Covid Vaccines the World Badly Needs,” New York Times, April 14, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/14/world/europe/western-vaccines-africa-hesitancy.html.

5 Ibid.

6 Denis Cenusa, “China, Russia and COVID-19: Vaccine Diplomacy at Different Capacity,” Italian Institute for International Political Studies, July 7, 2021, https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/china-russia-and-covid-19-vaccine-diplomacy-different-capacity-31070.

7 Ben Dubow, Edward Lucas, and Jake Morris, “Jabbed in the Back: Mapping Russian and Chinese Information Operations During COVID-19,” Center for European Policy Analysis, December 2, 2021, https://cepa.org/jabbed-in-the-back-mapping-russian-and-chinese-information-operations-during-covid-19/".

8 María Laura Chang, “COVID-19 Aid From China to Latin America Twice That of US as It Increases Investments in the Region,” Andrés Bello Foundation, October 20, 2020, https://fundacionandresbello.org/en/reporting/covid-19-aid-from-china-to-latin-america-twice-that-of-us-as-it-increases-investments-in-the-region/.

9 Adam Taylor, “Beijing and Moscow Are Losing the Vaccine Diplomacy Battle,” Washington Post, January 11, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/01/11/china-russia-omicron-vaccine/.

10 Kornelius Purba, “EU, the Preacher, Is in Love With ASEAN Yet Again,” Jakarta Post, June 14, 2021, https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2021/06/13/eu-the-preacher-is-in-love-with-asean-yet-again.html.

11 “Working Better Together as Team Europe,” European Union, https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/wbt-team-europe.

12 “The State of Southeast Asia: 2022 Survey Report,” ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute, February 16, 2022, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/state-of-southeast-asia-survey/the-state-of-southeast-asia-2022-survey-report/.

13 “Team Europe COVID-19 Global Response,” European Commission, September 25, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/FS_21_4897.

14 “COVAX Delivers Its 1 Billionth COVID-19 Vaccine Dose,” Africa Renewal, January 17, 2022, https://www.un.org/africarenewal/news/covax-delivers-its-1-billionth-covid-19-vaccine-dose.

15 “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations,” Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

16 Ruth Maclean, “Fighting a Pandemic, While Launching Africa’s Health Revolution,” New York Times, September 9, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/19/world/africa/africa-coronavirus-vaccines.html.

17 “New $50 Billion Health, Trade, and Finance Roadmap to End the Pandemic and Secure a Global Recovery,” International Monetary Fund, June 1, 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2021/06/01/pr21150-new-billion-health-trade-finance-roadmap-end-pandemic-secure-global-recovery.

18 “A Proposal to End the COVID-19 Pandemic: Update,” International Monetary Fund, March 17, 2022, https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/-/media/Files/Topics/COVID/pandemic/pandemic-proposal-update.ashx.

19 “2014-2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 8, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html.

20 “ASEAN Center for Public Health Emergencies and Emerging Diseases (ACPHEED),” Japan-ASEAN Integration Fund, December 29, 2020, https://jaif.asean.org/whats-new/asean-center-for-public-health-emergencies-and-emerging-diseases-acpheed/.

21 “Latin America and the Caribbean: Impact of COVID-19,” Congressional Research Service, January 21, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11581.

22 “From Vaccines to Recovery: A Test for EU-Africa Relations,” Carnegie Europe online event, March 29, 2021, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/03/29/from-vaccines-to-recovery-test-for-eu-africa-relations-event-7590.

23 Gordon Brown, “A New Covid Variant Is No Surprise When Rich Countries Are Hoarding Vaccines,” Guardian, November 26, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/nov/26/new-covid-variant-rich-countries-hoarding-vaccines.

24 “United States–European Commission Joint Statement: Launch of the Joint COVID-19 Manufacturing and Supply Chain Taskforce,” European Commission, September 22, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_21_4847.

25 Thokozile Madonko and Marlise Richter, “‘No-one Is Safe Until Everyone Is Safe’ Is a Valuable Piece of Wisdom That Should Be Used to Measure All Our Efforts Towards Global Solidarity, Says Health Rights Activist Marlise Richter,” Heinrich Böll Stiftung, September 6, 2021, https://in.boell.org/en/2021/09/06/global-solidarity.

26 “COVID-19 Vaccine Transparency,” Transparency International, March 2, 2021, https://www.transparency.org/en/news/covid-19-vaccine-transparency.

27 Fatima Hassan, “Omicron: Vaccine Nationalism Will Only Perpetuate the Pandemic,” Al Jazeera, November 28, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/11/28/omicron-vaccine-nationalism-will-only-perpetuate-the-pandemic.

28 “Africa’s Vaccine Manufacturing for Health Security,” discussion paper prepared for the conference “Expanding Africa’s Vaccine Manufacturing,” Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April 13, 2021, https://africacdc.org/event/virtual-conference-expanding-africas-vaccine-manufacturing/.

29 “European Parliament Plenary Session Statement by Executive Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis on Multilateral Negotiations in View of the 12th WTO Ministerial Conference,” European Commission, November 23, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2019-2024/dombrovskis/announcements/european-parliament-plenary-session-statement-executive-vice-president-valdis-dombrovskis_en.

30 Andy Bounds, “EU Loosens Defence of Pharma Groups on Covid Vaccine Patents,” Financial Times, November 24, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/2de43d0b-a59a-427f-bf4f-3d900ba49784.

31 Rosa Balfour, “Europe’s Global Test,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 9, 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/09/09/europe-s-global-test-pub-82499.

32 “Overview of the Commission’s Response,” European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/coronavirus-response/overview-commissions-response_en#economic-measures.

33 Adam Tooze, Shutdown: How Covid Shook the World’s Economy (New York: Allen Lane, 2021), 16.

34 Ibid.

35 “Annual Report of the Executive Board,” International Monetary Fund, October 4, 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/AREB/Issues/2021/10/01/International-Monetary-Fund-Annual-Report-2021-50074.

36 Martin Wolf, “A Windfall for Poor Countries Is Within Reach,” Financial Times, June 1, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/fe826780-c973-476f-b057-7a8aa678ec7b; Martin Wolf, “The G20 Has Failed to Meet Its Challenges,” Financial Times, July 13, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/c9448d15-8410-47d3-8f41-cd7ed41d8116.

37 “Global Recovery: The EU Disburses SDR 141 Million to the IMF’s Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust,” European Commission, April 5, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/it/ip_21_1555.

38 David McNair, “Why the EU-AU Summit Could Be a Turning Point—Even If the Headlines Disappoint,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 15, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/02/15/why-eu-au-summit-could-be-turning-point-even-if-headlines-disappoint-pub-86448.

39 “The State of Southeast Asia,” ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute.

40 “Phnom Penh Statement on the Post-COVID-19 Socio-Economic Recovery,” Association of Southeast Asian Nations, November 26, 2021, https://asean.org/phnom-penh-statement-on-the-post-covid-19-socio-economic-recovery.

41 “Africa’s Vaccine Manufacturing,” ACDC.

42 Karen Donfried and Wolfgang Ischinger, “The Pandemic and the Toll of Transatlantic Discord,” Foreign Affairs, April 18, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-04-18/pandemic-and-toll-transatlantic-discord.