Introduction

China’s rapid development has evoked a host of reactions from within and without. As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seeks to reassert itself in all aspects of citizens’ lives, promote unfair and nonreciprocal trade and investment practices, steal technology, and modernize its military, conventional wisdom is giving way to a new narrative about a vast and increasingly powerful country that combines resurgent authoritarianism at home with long-suppressed regional ambitions and revanchism abroad. Beijing’s rapid resurgence coincides with the end of a period of unrivaled U.S. power and wealth and a unipolar world order that had persisted since the fall of the Soviet Union. That era has passed, or some would say has wasted away.

The world is entering an uncertain era of revived great power competition and balance-of-power geopolitics. Russia and China are nursing grudges and redressing grievances on their peripheries and beyond. The United States has begun to shrug off responsibilities for the global order that it used to welcome, or at least grudgingly accept. Washington increasingly seems to be feeling overextended, disrespected, and preoccupied with domestic tasks. The U.S. president is devaluing the country’s alliances. Elsewhere, the Middle East remains in deep turmoil, and the European Union is not really united.

What is the best way forward for the United States with respect to China? A debate over this question has unfolded in the past few years. Many observers, especially those in what former president Dwight Eisenhower famously termed “the military-industrial complex,” believe that the United States needs to rearm and redeploy forces from the Middle East to the Asia Pacific to meet the emerging challenge head on.1 Others, including both realists and liberal internationalists, argue that Washington should disengage from former positions of preeminence in the Asia Pacific and withdraw to bastions beyond the reach of China’s new weapons systems.

Amid these conflicting recommendations, the United States’ friends and allies in the region, who have long benefited from the prosperity enjoyed under the Pax Americana, now are watching nervously to see how Washington will decide its future role. These countries also are watching Beijing uneasily and are sensing its growing strength and influence, yet they are still eager to seize the opportunities that China presents. In effect, U.S. regional partners remain anxious over the classic dilemma of wishing neither to be entrapped in unwanted conflict nor abandoned to an uncertain dependence on and vulnerability to a powerful neighbor, in this case, Beijing.

A logical starting point is to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the United States and China in the Asia Pacific and at large. The objective is to formulate a realistic and practical set of strategies and policies to meet the greatest challenge facing the two countries: how to protect and, to the greatest extent possible, advance their vital interests—particularly their shared interest in avoiding a devastating conflict. Achieving this will require a combination of military, diplomatic, and economic tools employed flexibly to coax relevant actors to accept non-zero-sum outcomes. This endeavor should start with the belief that China is neither as strong as many portray it to be, nor as weak as many wish it was.

Looking back, the United States has weathered many challenges in Asia before, including the devastating Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the stalemate on the Korean Peninsula in the early 1950s, its hurried retreat from Vietnam in the 1970s, and the rise of Japan as an economic competitor in the 1980s. These experiences exposed Americans to episodes of self-doubt and reassessment, only for them to see their country adapt, bounce back, and eventually thrive again. However, such renewal and adaptation was not automatic, nor swift, nor inevitable. Over the last twenty-five years, U.S. leaders have failed to grasp many opportunities and have made profound mistakes, such as the war in Iraq.

China is another such challenge. Meeting this call to action requires constructive thinking and a self-assured assertion of U.S. interests. This mentality must be combined with an understanding that China, too, has interests, which (in some cases) overlap with U.S. ones but often do not overlap and at times even directly conflict with U.S. positions. The goal is to find ways to translate this entangled web of interests into mutually satisfactory outcomes or, when that is not possible, at least to avoid disastrous outcomes. In a sense, the United States faces a test of self-confidence. Having risen to the occasion in response to challenges before, Washington cannot assume failure, but neither can it assume success. The American way long has been to careen between bouts of optimism and pessimism before settling on a practical course. This analysis is an effort to sketch out such a practical, forward-looking path.

Therein lies the key to managing competition and avoiding conflict between the resident great power in the Asia Pacific, the United States, and the rising power, China. The essential tasks for Washington are to create a coalition of values, norms, and interests that is flexible and adaptive to changing circumstances; to be willing to engage with China for mutual benefit when possible; but to be prepared to put up effective defenses against unfair, nonreciprocal, or coercive behavior when necessary.

Setting the Stage

Economic reforms have facilitated China’s resurgence. The country is emerging as a great power because in 1978 the collective CCP leadership under Deng Xiaoping, having been deeply traumatized by Mao Zedong’s dogmatic rule and the self-destruction of the Cultural Revolution, decided to experiment with reforming China’s state-directed economy and gradually opening its markets to international competition and investment. Since then, China has experienced historically unprecedented gross domestic product (GDP) growth of nearly double digits annually.2

China’s Resurgence and a U.S. Policy Rethink

China’s decision to allow its enormous low-cost labor force to participate in global markets opened the door to international trade. It became the world’s largest trading nation by 2013, according to the World Bank.3 China’s trade surged from around a 12 percent share of GDP in 1980 to about 62 percent by 2005, before declining to below 40 percent today amid slowing worldwide trade volumes and the collapse of commodity prices after the 2007–2008 global financial crisis.4 The World Bank estimates that China’s GDP reached $11.2 trillion in 2016, compared to a U.S. figure of $18.6 trillion.5 Additionally, Beijing has made great strides in research and development (R&D), as its spending increased by 18 percent annually between 2000 and 2015; Chinese R&D now amounts to 2.1 percent of GDP, compared to 2.7 percent of GDP for the United States.6

China’s military spending is growing as well. The question of how best to measure the country’s military spending is somewhat controversial, depending on whether certain expenditures are included in the calculations (such as veterans’ benefits, off-budget R&D spending, and other costs). The CIA World Factbook estimated that China’s military budget was over $200 billion in 2016, nearly one-third of the U.S. annual defense budget that year.7 For many years, Beijing’s military budget grew at double-digit rates, but in recent years this growth has slowed down to the high single digits. That said, the underlying budgetary totals have obviously been higher in more recent years. What is less contested is the fact that China has greatly enhanced its military capabilities since the late 1990s, while undertaking significant modernization efforts especially since 2015 to transform its military’s traditional organizational structure, recruitment practices, and training regimen.

The U.S. armed forces have only just emerged from years of budget sequestration that negatively impacted military readiness and acquisitions (a challenge exacerbated by the expense of waging relatively low-technology but high-cost wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria). Meanwhile, Beijing has moved into new areas, adding power-projection capabilities to a military that was long focused on border defense and an oversized domestic stability force. In naval terms, China effectively scuttled its imperial fleet in the fourteenth century, but the country is now rapidly acquiring a modern 300-ship navy with new and more capable equipment and lethal weaponry, a navy third in size worldwide behind those of the United States and Russia.8

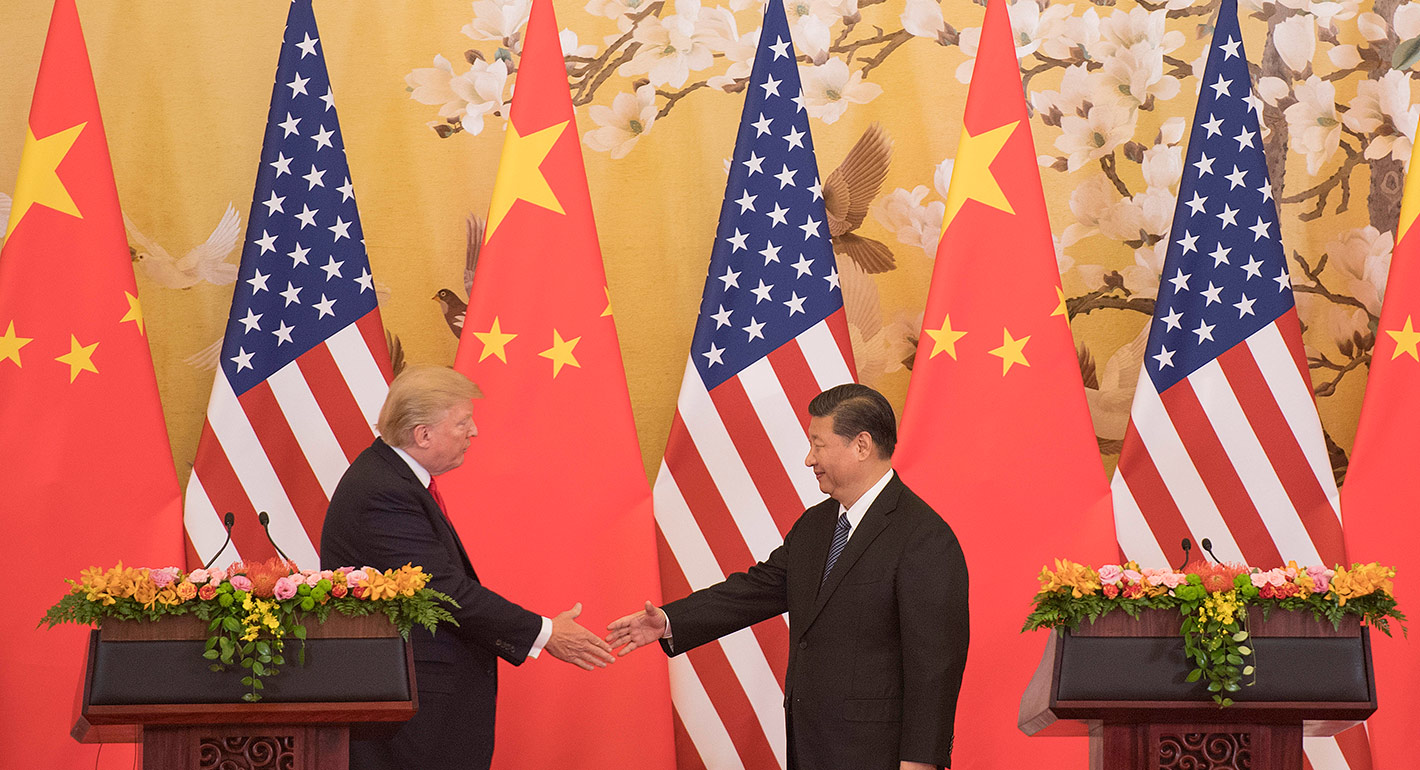

Notably, the U.S. National Security Strategy of December 2017 and the National Defense Strategy of January 2018 see Russia and China becoming great-power challengers, “rivals,” and potential threats. With regard to China, the National Security Strategy declares a new departure point that has since been echoed in numerous statements from the administration of President Donald Trump. It states:

For decades, U.S. policy was rooted in the belief that support for China’s rise and its integration in the post-war international order would liberalize China. Contrary to our hopes, China expanded its power at the expense of the sovereignty of others. China gathers and exploits data on an unrivaled scale and spreads features of its authoritarian system, including corruption and the use of surveillance. It is building the most capable and well-funded military in the world, after our own. Its nuclear arsenal is growing and diversifying. Part of China’s military modernization and economic expansion is due to its access to the U.S. innovation economy, including America’s world class universities.9

At the same time, the United States is reeling from prolonged political dysfunction among its elites and domestic economic challenges, such as unemployment, wealth inequality, and declining middle-class incomes. In the eyes of many Americans, the international security architecture and economic order Washington has nurtured since World War II increasingly seems to be working less for them and more for the benefit of others.

China has marched onto this stage. In general, the country’s macroeconomics are soundly managed and threats (such as excessive debt) are addressed swiftly as they arise. Beijing is promoting a grand industrial policy (known as Made in China 2025) that Americans see as a direct challenge to U.S. technological superiority, a policy predicated on what critics view as unfair Chinese practices such as intellectual property theft, espionage, and market-distorting subsidies. Moreover, in a world turning inward, China has propounded a grand international strategy focused on infrastructure investment billed as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the likes of which has not been seen since the Marshall Plan restored Europe.

At home, China is offering an illiberal alternative to the liberal development model for nations that are struggling between autocracy and democracy as they seek to modernize. Beijing is behaving in ways that are deeply unsettling and painfully reminiscent of the political repression and pervasive authoritarianism of the 1930s in Germany and the 1950s in the Soviet Union. The CCP is taking charge of every aspect of Chinese people’s lives, and the party’s leader—Xi Jinping—has been given seemingly unchecked authority without term limits. In a reversal of past practice, Xi has repeatedly displayed his leadership of the party, military, and government as well as his political dominance by appearing in uniform before parades of China’s newly modernized troops and ships, another custom unsettlingly reminiscent of the 1930s. Vast reeducation camps for the Uighurs, an ethnic minority in the region of Xinjiang in western China, have a similar 1930s-era, concentration camp–like quality.

In sum, a combination of American self-doubt and suspicions about Beijing’s intentions is fueling a fundamental rethinking of U.S. policy toward China. Simultaneously, a blend of Chinese self-assurance and resentment over past wrongs form a dangerous, volatile mixture that will require careful statesmanship for the countries to avoid disaster.

Intriguingly, some of the behavior of China’s neighbors suggests that they are not yet alarmed about Beijing’s new capabilities. For example, one expert on Asian arms acquisitions has concluded that, “despite considerable journalistic and scholarly attention to the impact of China’s new capabilities and influence, the behavior of China’s neighbors suggests a lower level of alarm there than in Washington.”10 According to David C. Kang, the region’s spending on arms acquisitions has been growing more slowly than that of the states of Latin America, a region rarely associated with high military spending. He writes that “the evidence on military spending in East Asia leads to the conclusion that although the region does contain potential flashpoints, countries are seeking ways to manage relations with each other that emphasize institutional, diplomatic and economic solutions rather than purely military solutions.”11

It should be noted that beyond former U.S. president Barack Obama’s administration’s pronouncement of the pivot to Asia, the United States has not yet significantly upgraded its military capabilities in the region. The U.S. military has had a dominant regional presence that may not in fact have required significant new investments before now, but that seems likely to change as China’s military modernization continues apace. China’s neighbors may then recalibrate their defense requirements in light of what Beijing and Washington decide to do.

The Terms of a Brewing U.S.-China Competition

As the United States summons itself to what some might term a new Cold War with China in Asia, what would be the best combination of strategies and policies to maintain and develop Washington’s long-term interests in the Asia Pacific (a region that the Trump administration prefers to call the Indo-Pacific)?12 Furthermore, how can the United States best deploy its assets and resources in relation to China and its neighbors to advance its own interests? At the same time, how can China continue to grow, raise the standard of living of its people, and develop its regional and global influence without doing so at the direct expense of the United States and its friends and allies in the region?

To begin, it is necessary to lay out several assumptions underlying this analysis. First, zero-sum thinking of the Cold War variety is not really an option for the United States. China is not the former Soviet Union; over the last thirty years, China has integrated with the rest of the world, not isolated itself. It is the world’s second-largest economy, top trading nation, and most populous country. It is one of the world’s leading exporters of high technology, much of which is American-designed and provides large profits for U.S. firms.13 Investment firms are betting U.S. pensions on the success of Chinese firms, many of which are registered on the New York Stock Exchange. Interdependence is deeply embedded in supply chains, in markets, and (increasingly) in the more remote domains of outer space and cyberspace. Delinking the two countries’ economies is not a realistic option. Neither can China be contained. Even if the United States tried to do so, China’s neighbors would not cooperate in the absence of a much greater threat to their own interests than has been evident so far.

Second, it must be noted that trying to change China to make it more like the United States is nothing more than wishful thinking. It is a complex country with complicated people and deep traditions that have served it well for centuries, even if some of those attributes are ones that Americans would not accept. Those authoritarian traditions are increasingly in conflict with the needs of a drastically modernizing economy and a fast-rising middle class; after all, if China were to try again to close the door on the rest of the world to retain control, that would also mean shutting the country off from the creativity required to compete. As historian Jonathan Spence wrote decades ago, many a foreigner has fallen short trying to plant foreign values in Chinese soil.14 That is not to say that outsiders are without influence or have no friends (or enemies) in China, or that the country never changes. Rather, it is a matter of harboring realistic expectations.

Third, China’s complex relationships at home as well as those with its neighbors and its far-flung trading and investment partners mean that the country often aims to shape policymaking so as to meet multiple objectives and to avoid setbacks to its interests. While the country clearly has an expanding range of external interests and activities, its primary concerns, as evidenced in every major Communist Party meeting, are domestic, as seen in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Party Congress work reports.15 Washington should seek to help Beijing shape its choices by using military, diplomatic, and economic tools to affect China’s calculations of benefits and risks with relation to its domestic and international environment. In this respect, the United States’ demonstrated capacity for coalition building gives it a special advantage over a frequently isolated and awkwardly led China.

Since the end of World War II, the United States has been primarily a maritime power in Asia. Over time, its air power developed a similar dominance. It has enjoyed an unchallenged ascendancy, or what some call primacy, in these domains. After the partial settlement of the conflict on the Korean Peninsula, and then the withdrawal from Vietnam, Washington has relied on a network of alliances and arrangements with friendly powers to support its maritime and air presence in the region. For the most part, except for major deployments in South Korea and token deployments in Thailand, these arrangements have not focused on the Asian mainland but have been made with islands (Japan, the Philippines, and Taiwan) that make up what China often calls the First Island Chain.

China is developing blue-water naval capabilities that can challenge the U.S. and allied military presence in the region. In 2012, then CCP general secretary Hu Jintao proclaimed that China would become a “maritime power.”16 As Admiral Mike McDevitt has argued, this was the culmination of a decade of examination and planning to secure China’s extensive vulnerable maritime approaches and the coastal provinces where the country is most economically developed.17 The policy aim was also to support China’s long-standing but legally questionable claims associated with the so-called nine-dash line, an area that encompasses about 80 percent of the South China Sea and overlapping claims by other littoral nations based on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This new point of emphasis was graphically underscored by China’s decision to create several artificial islands on rocks, reefs, and low-tide elevations in the Spratly archipelago in the South China Sea in 2014 and 2015. China has gradually built facilities on these islands that could quickly be adopted for military use.18

This development is playing out in close proximity to important U.S. regional partners. To the east of the South China Sea lies the Philippines, a long-standing U.S. ally. Under the terms of a mutual defense treaty, a succession of basing agreements kept U.S. forces in the country until 1992, when the Philippine Senate rejected the last such agreement. In light of China’s growing level of activity in the South China Sea, Manila agreed to a new ten-year Visiting Forces Agreement with Washington in 2014.19 The agreement persists, but its implementation slowed with the 2016 election of President Rodrigo Duterte, who has focused on avoiding friction with Beijing and seeking bilateral assistance from China.

Farther north in the First Island Chain is Taiwan. It is also a claimant to rights in the South China Sea, but it figures more importantly as a former ally of the United States over which mainland China claims sovereignty. In the course of developing its relationship with mainland China in the 1970s, the United States acknowledged Beijing’s assertion of sovereignty over Taiwan, but Washington also developed a deliberately ambiguous relationship with the island. Under the terms of the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979, the United States provides “defensive arms and services” to the island’s armed forces, an arrangement that is a frequent source of tensions between Washington and Beijing.20

Still farther north, the Japanese archipelago constitutes the most formidable part of the First Island Chain, extending northward to the Kuril Islands that lead to Russia’s Far East. Japan and China contest sovereignty over a small island group between the mainland and Japan: the Senkaku Islands (known in Chinese as the Diaoyu Islands). The United States considers Japan to be the administrator of the disputed islands, and successive administrations have asserted that they are therefore covered by the U.S.-Japan mutual defense treaty. China nonetheless routinely patrols the waters around and contingent to the unpopulated islands to undermine claims that Japan effectively controls them.

In sum, a China that is increasingly dependent on maritime trade faces potential choke points from the Straits of Malacca near Singapore to the Kuril Islands north of Japan. Beijing’s development of a blue-water navy to protect its increasingly far-flung interests and to supplement its traditional brown-water coastal fleet raises the prospect of guaranteeing access to the world’s oceans in the waters along China’s coastal provinces and within the First Island Chain. This development has invited comparisons to the United States’ articulation of the Monroe Doctrine in the early nineteenth century to prevent European powers from challenging its interests in the Western Hemisphere. Many realists envision inevitable conflict between the United States and its allies and China as the latter develops into a regional hegemon.21

As time passes, China’s concerns about developing a security buffer as well as its irredentist claims over Taiwan, Japanese-controlled islands, and the South China Sea will continue to morph beyond ambitions to develop conventional sea- and air-based military capabilities and extend to the cyber, space, and strategic domains. This will force the United States and China’s neighbors to make choices about how to protect their interests from new threats in those domains.

Conceptual Frameworks

There is an extensive and growing body of literature on how to manage the challenge from China in the Asia Pacific. This literature contains a few widely used historical and conceptual frameworks designed to help analysts understand U.S.-China relations. Different branches of the realist school of international relations provide useful lenses to understand this relationship. These conceptual frameworks and schools of thought have been a major feature of the ongoing conversation about how the United States and its allies should respond to China’s reemergence.

One of the most prominent such frameworks is the Thucydides Trap, which refers to the almost inevitable tendency for relations between an established power and a rising one to devolve into competition and conflict. Numerous scholars have studied historical examples of the Thucydides Trap to assess whether it applies to the contemporary situation between the United States and China.22 Most prominently, Graham Allison views the Thucydides Trap as a useful way of understanding U.S.-China relations.23 However, instead of focusing on the perceived inevitability of conflict, he defines the Thucydides Trap as the inevitable unease that accompanies a sharp shift in the relative power of potential competitors. For Allison, the unease and tensions in U.S.-China relations are real as much as they were in Athenian-Spartan relations, but a conflict between the two countries is much less likely today. Numerous crisis-management mechanisms between Beijing and Washington reduce the likelihood that a crisis would evolve into a full-blown war.

Meanwhile, David Richards argues that the Thucydides Trap is a tempting conceptual framework but an imperfect one.24 He offers several important differences between U.S.-China relations and other case studies on which the Thucydides Trap is based, particularly Athenian-Spartan relations before the Peloponnesian War and Anglo-German relations before World War I. He asserts that the Chinese and U.S. nuclear arsenals significantly reduce the likelihood of war between the two countries. He also views the political leadership in Beijing and Washington as much more mature and stable than that in monarchic Europe. Furthermore, Richards sees the globalized economy and intricate international commercial links as major impediments to China and the United States waging war against each other.

In addition to historical frameworks and comparisons, some scholars offer other theoretical models for understanding contemporary U.S.-China relations. For example, John Mearsheimer argues that his theory of offensive realism is the ideal lens through which to understand the relationship.25 Offensive realism posits that under an anarchic, decentralized international system, states are inherently unsure of each other’s motives and inevitably seek to maximize their relative power to ensure their own survival. In such an environment, conflict becomes inevitable between an established power that seeks to maintain its relative strength and a rising one that seeks to increase its relative strength. According to Mearsheimer, the rise of China and the resulting security competition between Beijing and Washington will eventually result in war.

The theory of defensive realism also acknowledges the possibility of conflict between the United States and China, but it views this outcome as much less likely. According to Charles Glaser, for instance, defensive realism takes into account the moderating influence of the international system on the security dilemma between the two great powers.26 Given that the United States and China are deeply integrated into the current system, Glaser argues, defensive realism is a better framework for understanding the ties between Beijing and Washington.

Meanwhile, former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd has proposed a constructive realist view of U.S.-China relations.27 His position is realist in the sense that it recognizes that some kind of confrontation between the two countries is likely inevitable, but at the same time his perspective is constructive in the sense that it urges the two countries to identify regional flashpoints that could become a source of conflict and preemptively manage them so as to avoid an inadvertent escalation to war.

Assessing China’s Current Capabilities

The aforementioned conceptual models and schools of thought offer an array of ways that scholars and practitioners have thought about the competitive dynamics between China and the United States. Each of them, in their own way, addresses the question of how much power Beijing will accrue and how this will shape U.S.-China relations.

There are, broadly speaking, two schools of thought when it comes to assessing how powerful China is. One emphasizes the country’s growth and argues that the rise of China is significant enough to pose a serious challenge to U.S. primacy in the Asia Pacific. Alternatively, the second school of thought highlights the limits of Beijing’s power and argues that China’s influence is still far below that of the United States, which is argued to still have the means to restrain excessive Chinese behavior and shape Beijing’s rise.

China’s Growing Power: Numerous scholars argue that China’s economic influence and military capabilities will make the country strong enough to disrupt or even undermine U.S. primacy in the Asia Pacific. For example, Aaron Friedberg and Hugh White are united in their assessment that the rise of China will pose an unprecedented strategic challenge for the United States.28 Friedberg explains that the size of China’s population and its growing role in the global economy offer Beijing enormous power and influence over other countries.29 White argues that China’s wealth will become an essential source of power and help elevate the country’s status in the Asia Pacific and relative to the rest of the world.30 He assesses China’s strategic and political strength as greater than that of any other rival the United States has faced. Similarly, Robert Blackwill and Ashley Tellis also define Beijing as the most significant competitor Washington will contend with in the decades to come.31

Like these other analysts, Michael Swaine argues that the Asia Pacific is undergoing an undeniable shift in the balance of power between the United States and China.32 In the long run, he observes that this transition is most likely to intensify to the extent that, by 2040, China’s economic and military capabilities could very well be on par with those of the United States. Given present trends, Swaine predicts that the United States’ predominant position in the Asia Pacific will disappear over time as its economic growth continues to falter and constrains its defense spending. Meanwhile, he expects China’s economic growth to remain robust and to cause proportionate increases in Beijing’s defense spending. Swaine concludes that China may not have the capabilities to pursue dominance, but that it will most likely be on equal footing with the United States.

These trends toward competition and possible parity notwithstanding, relations between Beijing and Washington may be more complex than a straightforward rivalry. Friedberg, for instance, asserts that China defies simple categorization as a U.S. friend or enemy.33 The United States enjoys close commercial relations with China, but the two countries have irreconcilable ideological and political differences. The coexistence of cooperative and competitive elements in the relationship will make it difficult for Washington to formulate a consistent policy vis-à-vis its strategic rival.

China’s Limited Power: Other scholars offer a more modest assessment of Chinese power. They argue that Beijing faces numerous domestic challenges and that the United States’ strategic edge is likely to continue for the foreseeable future. For instance, Henry Kissinger predicts that China’s domestic challenges—from demographic to economic problems—will be major impediments to Beijing’s ability to seriously challenge the United States in the Asia Pacific.34 Joseph Nye points to the economic gap between rural and urban parts of China as a serious problem for the country’s continued growth.35

While scholars generally agree that China will eventually replace the United States as the largest economy in the world, several observers nonetheless argue that Washington will maintain key strategic economic edges. Nye argues that China’s financial system is not deep enough to challenge the dominance of the dollar as the predominant reserve currency and that the U.S. technological sector is much more innovative than China’s.36 Similarly, Thomas Christensen notes that the United States has a much higher per capita GDP and much more sophisticated technological industries.37 Andrew Nathan and Andrew Scobell, meanwhile, predict that Beijing will need much more time than many expect to convert its economic power into political influence and military power.38

Some scholars are confident that the United States can continue to have much more influence than China in terms of diplomatic and military power. From Nye’s perspective, there is no doubt that the United States will maintain its military superiority, and its allies are a unique strategic asset that China does not possess.39 Similarly, Lyle Goldstein and Barry Posen also posit that the presence of key U.S. allies and friends will help restrain excessive Chinese behavior.40

Beyond current trendlines, it is also possible, however unlikely it seems in the face of forty years of Chinese advances, that the recent choices made by the country’s Communist leadership to rely on virtual one-man rule over 1.4 billion people, and to burden the economy with a still massive state-owned enterprise (SOE) sector, may prove fragile and counterproductive. Should these decisions eventually result in disarray, disintegration, internal conflict, or economic recession, the kinds of security and humanitarian challenges China would pose for its neighbors and the United States would be equally consequential but of an entirely different character.

Projecting Future Chinese Behavior

Views on China’s future behavior can generally be categorized into two camps. One side sees China as a revisionist rising power determined to challenge the status quo and U.S. primacy. The other group sees Beijing as a restrained rising power that seeks a greater role in the present international system despite its dissatisfaction with certain aspects of the current order over which it previously had little or no voice. The fact is that reality has outpaced this debate. Over the past ten years, early gestures under Hu meant to break China out of Deng’s hide-and-bide (taoguang yanghui) restraints have matured into a fuller agenda of Chinese assertiveness and aggression under Xi. The latter’s China Dream concept encompasses large ambitions at home and abroad that are impinging positively and negatively on the interests of China’s neighbors and the United States.

A Revisionist Rising Power: Numerous scholars have argued that Chinese foreign policy makers will continue to be much more assertive and eventually will seek to overturn the status quo in Asia and globally. Mearsheimer has argued that Beijing will seek regional dominance and expand its efforts to expel the United States from the Asia Pacific.41 He also has contended that nationalism and realpolitik strategic thinking will most likely drive China to become more aggressive in the region. Similarly, Charles Glaser has argued that, given the country’s increased military capabilities, China’s stronger political leadership is much more determined than its predecessors to pursue the country’s vital regional interests.42 He has echoed Mearsheimer’s assessments and predicts that nationalism will play a major role in making Chinese foreign policy more aggressive.

Mearsheimer and Glaser are not alone in their judgments. Kurt Campbell has argued that China took an assertive turn after the 2007–2008 global financial crisis and that U.S. economic failures gave Beijing greater confidence to reassert itself in Asia.43 Furthermore, Xi has taken radical steps to concentrate power in his own hands and promote assertive policies, even as the Chinese party-state’s longtime emphasis on nationalist education has paved the way for broad public support for more assertive Chinese actions abroad. Campbell also underscores that China’s military modernization constitutes an attempt to transform the strategic balance in the Asia Pacific. He views China’s position and policies on territorial disputes in the South China Sea as capable of compromising key principles such as freedom of navigation. In addition, he sees Beijing’s cyber espionage as further evidence of a more assertive foreign policy. Campbell and Ely Ratner more recently have pronounced the failure of U.S. efforts to encourage China to make its political system and international behavior converge more with those traditionally advocated by the United States at home and abroad.44 Meanwhile, Blackwill and Tellis claim that Beijing seeks to fundamentally alter the balance of power in the Asia Pacific, to weaken the U.S. alliance system, and to eventually replace the United States as the region’s dominant power.45 They conclude that China’s grand strategy aims to undermine vital U.S. interests.

By virtue of these views, Mearsheimer concludes that the rise of China and its growing influence, assertiveness, and aggression in the Asia Pacific will inevitably trigger an intense security competition with the United States. Friedberg similarly concludes that the two countries are engaged in an intense struggle for power and influence not only in the Asia Pacific but also around the world. According to this logic, the causes of this competition are not misperceptions or readily correctible policies, but instead a gradual shift in the international system and deep differences between the two countries’ political ideologies and forms of governance.

A Restrained Rising Power: Other scholars view China as a restrained rising power and advise the United States not to overstate its capabilities or exaggerate the threat it poses.46 Posen and Nye consider China’s capabilities to be limited and thus say it is unlikely that Beijing will embark on a path to become a regional hegemon.47 They and Goldstein claim that Chinese regional dominance is highly unlikely due to the presence of strong neighbors like Japan and India that will counterbalance its excessive behavior.48 Goldstein also argues that more assertive Chinese behavior will only compel countries in the Asia Pacific to reach out to the United States, which will, in turn, strengthen regional U.S. security arrangements.49

Other notable scholars are of a similar mind. Nathan and Scobell argue that China’s preoccupation with domestic stability and economic growth will probably reduce the likelihood that the country would wage war against other nations.50 They further claim that China has neither the capability nor the interest to replace the United States as a global hegemon. According to this viewpoint, Beijing would not welcome a U.S. decline, as such an outcome would entail global instability, which would eventually affect Chinese economic growth. Along the same lines, Posen argues that China’s deep integration with the rest of the global economy and the country’s record of economic success will create more incentives for Beijing to preserve the global economic system.51 Similarly, Rudd predicts that China will not wage war against the United States in the near future because such a conflict would adversely affect its economic growth.52

Ultimately, this camp of scholars conclude that China’s revisionism is limited in scope. Nathan and Scobell recognize that China is somewhat dissatisfied with the current role it has in the international system, but at the same time they maintain that Beijing does not have a viable alternative.53 While they admit that China may become more assertive and even aggressive to some extent, they still do not see it as a revisionist power determined to overthrow the system as a whole. According to Rudd, China will seek to become an even more active participant in the current global order for its own benefit.54 As for China’s rapid military modernization, Rudd argues that it is not an attempt to replace the U.S. order in the Asia Pacific, but a strategy to deter the United States and diminish its confidence in its own military capabilities there.55 Nathan and Scobell explain that China has been preoccupied with ensuring its own territorial integrity and has shown no intention of engaging in territorial conquest.56 Similarly, Christensen states that, while its coercive capacity should be a concern for the United States, this by no means indicates that China will actually seek regional dominance.57

The Landscape of Proposed U.S. Policy Options

The various proposals that analysts and policymakers have made for how the United States should manage the rise of China can be categorized into four different ways of thinking: seeking to contain China, establishing a new balance of power, striving to integrate China further into the international system, and crafting a new world order. On the whole, engaging Beijing, with an increased emphasis on balance-of-power politics, still appears to be the most promising or least risky approach to long-term U.S. policy toward China.

Containing China

Scholars who view China as a credible threat to U.S. primacy in the Asia Pacific propose a strategy of containment. Based on his predictions about the inevitability of conflict between the two countries, Mearsheimer proposes that Washington pursue an active form of containment and a balancing coalition against Beijing.58 He explains that the other available options are preventive war and deliberately slowing down the Chinese economy, both of which would be extremely costly and riskier than containment. The key objective of such a containment strategy and overarching U.S. grand strategy would be to preserve U.S. primacy in the Asia Pacific.59 The following elements of this type of approach are drawn from analysis by Friedberg, Blackwill, and Tellis.60

- Develop strategies and capabilities to counter Chinese anti-access and area denial measures and ensure the survival of U.S. forces in the Asia Pacific.

- Make investments to ensure an effective nuclear counterstrike capability.

- Reexamine export control provisions and take other steps to protect technologies that have national security implications.

- Implement an effective cyber policy to protect military secrets and intellectual property.

- Expand U.S. trade networks in the Asia Pacific.

- Reinforce U.S. regional alliances as well as partnerships with non-allied friendly countries like Vietnam.

- Assist in developing updated means to communicate information to the Chinese people.

- Find ways to encourage Chinese civil society to help promote values that the Chinese regime is suppressing.

- Enhance high-level communication channels with Chinese leaders.

Other scholars, however, view the prospect of a U.S. attempt to contain China as infeasible and unwise. Posen argues that it would be premature and wrong to do so, given Beijing’s limited capabilities and the unfavorable environment for Chinese dominance in a region where many neighbors already wish to keep their distance from Beijing.61 Furthermore, he suggests that containment could eventually backfire, given that other countries in the Asia Pacific would most likely reject a regional Cold War. Christensen argues that U.S. allies would not join efforts to contain China and that attempts to coerce them into joining such a coalition would do irreparable damage to the U.S. alliance system.62 He rejects the underlying premise of a zero-sum U.S.-China relationship and states that both sides have mutual interests they can pursue together. Nathan and Scobell similarly argue that containment would be too costly and would inevitably damage the mutually beneficial economic relationship between the United States and China.63

Establishing A New Balance of Power

Some scholars who view the United States and China more or less as equals propose the formation of a balance of power that encourages mutual restraint and maximizes cooperation. They argue that neither country will dominate the Asia Pacific and that any attempt to oppose each other will likely result in war.

Accordingly, they propose mutual accommodations that would entail accepting each other’s presence in the region. For example, Posen argues that, given its diminishing strategic edge over China and India, the United States needs to adopt a strategy of restraint designed to serve limited political and military purposes.64 He argues that the ideal strategy would be a balance-of-power approach that would reassure U.S. allies in the Asia Pacific and maintain the United States’ strategic edge over China. He advocates building a coalition, but he indicates that Washington must demand that its allies develop their own defense capabilities and not merely rely on U.S. security commitments. According to this perspective, these U.S. partners would need to take on a greater share of defense costs and, if necessary, the United States would have to acquiesce to some of them acquiring nuclear weapons.

Similarly, White argues that the United States must accommodate China and seek joint leadership in the Asia Pacific.65 In his estimation, attempts to oppose each other’s regional presence would most likely lead to conflict. To avoid this, White maintains that the two countries will have to come to an agreement on their respective regional roles. In other words, his position is that negotiations should aim to give China a bigger role in Asia while allowing the United States to retain a major one.

Other scholars have made similar recommendations. Swaine argues that the United States and China should enter a serious discussion on how to manage regional hotspots and preserve peace in the Asia Pacific.66 The two countries would need to hold long-term, deliberate, and honest discussions to erase strategic mistrust. Based on these talks, they would need to incrementally build a stable balance of power that would discourage conflict and encourage restraint. In the short run, Washington and Beijing would have to discuss their expectations of each other and neutralize some issues such as Taiwan and the Korean Peninsula. If each side can eventually adopt a force posture that encourages restraint, they would be better able to avoid a catastrophic conflict.

Likewise, Goldstein argues that the United States and China should make mutual concessions and meet each other halfway since neither of them will dominate the Asia Pacific.67 This two-way pattern of accommodation based on incremental steps would likely minimize mutual suspicions and enhance security and stability in the region. Goldstein does not see U.S. concessions as a form of appeasement but rather as a bold step designed to trigger a cooperative spiral with China. He offers detailed scenarios that would involve the United States revising or reviewing its policy on one area of potential conflict, encouraging China to respond in kind. The United States should clarify its commitments to allies in the Asia Pacific so as not to be dragged into conflict with China over matters of little strategic importance. The best strategy, Goldstein proposes, is to continue offshore balancing and adopt a purely defensive posture.

Glaser has proposed a more radical version of a new balance of power and a U.S.-China grand bargain.68 This approach would entail ending U.S. security commitments to Taiwan in exchange for Beijing’s commitment to resolve territorial issues fairly and peacefully and to accede to a long-term U.S. presence in the Asia Pacific. Glaser views this grand bargain as a way to enhance cooperation and limit confrontation. As he sees it, the benefits outweigh the costs: this approach would substantially reduce the potential for conflict, significantly curtail China’s strategic mistrust of the United States, and greatly moderate the military competition between the two sides. Glaser also argues that if China were to commit to reaching fair terms with its neighbors and to reaffirming a long-term regional U.S. military presence, this would signal that Washington would still remain committed in Asia, through an explicit agreement with Beijing, despite any security commitments it would relinquish vis-à-vis Taiwan.

Admittedly, some scholars are highly skeptical that such a deal would ever materialize. For Blackwill and Tellis, there is no prospect of the United States and China reaching a modus vivendi regarding a balance of power in the Asia Pacific. In their view, Washington cannot reconcile the fundamentally different goals of accommodating Chinese concerns regarding U.S. power projection in Asia and defending vital U.S. interests in the region.69

Further Integrating China

Other scholars who believe that the United States still has a strategic edge advocate for further integrating China into the existing international system. Nye argues that Washington should continue seeking to further embed China in the global order, but should also assure allies that it would deter Beijing if it became assertive. The United States should continue to shape the environment in which China makes strategic decisions.70 Meanwhile, Nathan and Scobell argue that the United States should maintain the current international system but give China a greater role in it.71 They view China not as a revisionist power but as a disgruntled stakeholder in the current order, arguing that Beijing’s power and influence are by no means at a level requiring Washington to yield to it or completely restructure the international system. They conclude that ideally the United States would manage China’s rise by striking a delicate balance between maintaining its presence in the Asia Pacific and giving China a bigger role in the international system.

Similarly, Christensen argues that the United States must incentivize and encourage China to become more integrated into the international system.72 He advises Washington to focus more on encouraging countries to correct specific unacceptable behaviors, but not going so far as to overthrow their governments, as happened in Libya in 2011. Regime change anywhere in the world would be viewed as a threat to the CCP regime and, therefore, could lead China to avoid responsibility for helping maintain the existing order. The United States should embrace more multilateral initiatives that involve China, seeking to align the priorities of the rest of the international community with Chinese domestic priorities to convince Beijing to play a more active role. Christensen emphasizes that the United States should seek to adopt policies that can shape China’s choices in positive directions and channel its nationalist ambitions toward cooperation rather than coercion. According to this view, Washington has the power to impact Beijing’s perceptions and potentially change its strategic calculus.

Building a New World Order

Another way to address potential pitfalls in U.S.-China relations is Kissinger’s proposal to form a Pacific community.73 In addition to bilateral dialogues and multilateral forums, this vision would entail that both countries strive to develop a community grounded in solid bilateral relationships, a community in which they can peacefully participate and manage confrontation. Such a community, one that includes both the United States and China, would be needed to defy the prevailing narratives of strategic mistrust that tend to focus on U.S. containment of China or Chinese attempts to push the United States out of Asia. Kissinger recognizes that this would not be an easy task, but he argues that taking this step is absolutely necessary in the long run if both countries wish to avoid a serious conflict.

Likewise, Rudd argues that the United States and China should develop an explicit agenda for cooperative strategic projects to build mutual trust and reduce strategic mistrust.74 His view is that Washington and Beijing should identify key regional hotspots and clearly understand the differences between them. They should manage these issues carefully so that none of them completely derail the overall relationship. Rudd also argues that the United States and China should embark on a bold attempt to reform the international system and build an Asia Pacific community. The two countries should seek to recalibrate dysfunctional aspects of the current system and add elements that can address unprecedented global challenges, because both sides share a responsibility on behalf of the world to tackle these challenges for the benefit of humanity.

Which Path to Choose?

The author’s largely practical experience in dealing with China argues in favor of a combination of the balance-of-power and integrationist approaches. The United States remains strong enough in the Asia Pacific, despite such negative steps as abandoning the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement championed by former president Barack Obama’s administration and prolonged delays in military acquisitions. Washington need not resort to a cut-and-run approach.75 However, the United States cannot maintain its regional presence and influence successfully only by relying on present trends and momentum. China’s military modernization is making some U.S. military equipment and facilities in the region obsolete and insufficient. A comprehensive approach based on this combination of balance-of-power and integrationist considerations would be most desirable. This would entail integrating diplomatic, political, economic, and security strategies in light of global and regional realities. Complacency is not an option.

In the past year, the Trump administration has attempted to forge such a comprehensive approach, judging from the vision set out in its National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy. But based on the author’s interviews throughout the region with current and former officials, the message is not getting through.76 Considerable lip service has been paid in the United States to the concept of a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” a formulation implicitly in contrast with Chinese efforts to challenge existing rules and norms in the region. Most outside observers, however, do not believe this concept has risen above the status of a slogan to become operational policy guidance. By virtue of Washington’s abandonment of the TPP and instigation of multiple bilateral trade disputes, there is a growing sentiment among many policymakers and other observers in the Asia Pacific that the United States under Trump is drifting away from its traditional role and values in the region. Japan’s subsequent championing of an amended trade agreement called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP-11) in 2018 proved this point.

Admittedly, some experts have criticized the integrationist approach for failing to accomplish the supposedly long-standing U.S. goal of inducing China to become an increasingly liberal regime.77 And it is true that recent developments in the country’s politics are reinforcing authoritarian tendencies. However, it is unclear that changing China’s domestic political system and values actually was a persistent feature of the U.S. integrationist efforts since diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China were established in 1979. There was a noticeable and brief effort in the first two years of former president Bill Clinton’s administration to force China to relax its stance on human rights that ended in an embarrassing retreat when Beijing refused to give in. But most policy articulations by successive U.S. administrations have focused on China’s international behavior and domestic economic development, not on changing its political system.

Besides, the historical record shows that the international community actually has enjoyed considerable success at integrating China into various multilateral arrangements. For example, Beijing has joined the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In addition, China has gone from being a nuclear and missile proliferator to participating in the Non-Proliferation Treaty and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. In recent years, Beijing generally has avoided the use of force in international disputes and avoided conflict specifically over the sensitive topic of Taiwan.

China’s behavior has improved over the past few decades in other respects as well. Beijing contributed critically to worldwide economic growth during the global financial crisis and has opened itself more to exports and investment from the United States and other countries, though not completely. Moreover, China has restored its global trade surplus to normal levels after an aberrantly high period following the financial crisis. Meanwhile, Beijing has cultivated productive diplomatic relationships with South Korea and Israel, a prospect that was previously considered anathema. Additionally, China has banned the trade of ivory and curtailed trade in endangered species; Beijing also signed—and is meeting—the terms of the Paris Agreement of the Convention on Climate Change. Separately, China reached an agreement with the United States in 2015 to curb commercial cyber theft, with reportedly positive results.78 And more recently, Beijing has made a new contribution to the global economy by establishing the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which operates on terms that many consider an improvement on those of other international financial institutions in some respects.79

Moreover, China’s recent efforts at home to strengthen the dominance of the CCP and to recentralize authority are not necessarily permanent and may prove transient. Today’s elites seem to know instinctively what they have to do to get along with authority figures, even if they grumble as they submit. That said, their grumbling does sometimes involve acknowledging that limiting intellectual freedom may well in time produce a high (and even unacceptable) cost in terms of limiting creativity and productivity.

In addition, other Asian countries, including South Korea, Taiwan, and (to an extent) Singapore, have seen authoritarian regimes go through phases of tighter control to deal with internal challenges, but then ultimately allow greater openness under pressure from their populations and in order to advance up industrial value chains. Therefore, it could be a mistake to assume that recent setbacks to China’s integration in the international system and the values it represents are necessarily permanent. It would be prudent for the United States to try to devise incentives and disincentives that reinforce rather than forestall a more positive adjustment on China’s part.

In short, the record of U.S. balance-of-power and integrationist policies toward China is at least one of mixed success so far, and this combined approach leaves open potential pathways to less confrontational outcomes. These methods offer the important diplomatic advantage of not forcing China’s neighbors to choose between U.S. and Chinese preferences, but rather to allow such countries to work with Beijing and Washington as counterweights to each other. This approach should lead to stability over time if implemented steadily. As Kissinger and Rudd have implied, Beijing and Washington will have to sort out their differences in the region gradually. The concept of a grand bargain between the two sides over sensitive issues such as the future of Taiwan or the Korean Peninsula seems ultimately elusive or even dangerous. The people of these lands will have their own say as well.

Additionally, this approach accounts for the contrasts between common U.S. and Chinese policy tendencies. U.S. policymaking tends to be ad hoc, transparent, and event-driven. By contrast, Chinese policymaking is often obscure, opportunistic, and calculatingly risk-averse. Both sides operate under often incongruent principles they will not easily abandon or bend. Consequently, U.S. leaders who may try to force the question or roll the dice on thorny subjects like the future of Taiwan or the Korean Peninsula seem destined to fail if their policies are not embedded in a sound long-term strategic calculus.

These limitations suggest that the soundest course will be an incremental policy governed by a comprehensive grasp of balance-of-power considerations. Political leaders naturally seek to advance their respective countries’ interests while avoiding costly clashes with others. China is a growing power with interests that are increasingly far-flung. As an established power with a significant presence globally and in the Asia Pacific, the United States has interests and friends that it will not readily surrender. Going forward, China will want to develop the influence it believes it deserves, and the United States will not be able to stop it from doing so at acceptable costs. Navigating between these forces without sparking conflict is the great challenge of the coming decades.

An Assertive China and the Future of the Asia Pacific

Diplomatically and politically, it is a given that the United States should work to protect and advance its long-standing interests in the Asia Pacific. Even when U.S. leaders express fatigue or frustration about overseas commitments, the American people through Congress and over the course of successive administrations have acknowledged the value of these commitments to U.S. interests by supporting U.S. alliances and other security arrangements.

This assumption is being jolted by the emergence of considerable fluidity in great-power relations. China is the most relevant other great power in the region, but India, Japan, Russia, and the countries of Southeast Asia all should be part of U.S strategy as well. The Trump administration has identified China and Russia as revisionist rivals, reducing the potential for relations based on naive illusions, but at the same time not creating much of a foundation for cooperatively managing global affairs. Under such circumstances, leaders are less likely to reach compromises and solutions unless they feel compelled to do so. Attention must be paid to concrete and compelling security, diplomatic, and economic arrangements and capabilities, beyond appealing to the goal of shared governing principles and norms.

Yet, in the long run, peace and prosperity maintained through principles and norms are likely to be much less costly than the alternatives, as seen during the long post–World War II general peace in the Asia Pacific. Small countries did not have to arm to the teeth to protect themselves as they pursued development during the Pax Americana. That state of affairs is now being challenged by China’s rise as a potential U.S. rival. The goal is to find a way for the two countries to share the responsibility for developing a new environment where rules and norms continue to prevail over contests of strength. A key element of that endeavor is to persuade China that a hegemonic alternative, achieved by overawing its neighbors, is not available. It is necessary to attend to relevant security requirements and to update strategies, tactics, and capabilities to accomplish this in light of China’s modernized capabilities.

In the 1990s, as China emerged from the renewed isolation caused by the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident, Deng devoted careful attention to improving relations with China’s neighbors, thereby decreasing the effectiveness of then U.S.-led post-Tiananmen sanctions. He advocated that China should lower its profile, a strategy encapsulated in the phrase taoguang yanghui, which is sometimes translated as to hide one’s capabilities and bide one’s time. Deng and his senior colleagues invested time and talented personnel in strengthening neighborly relations. During this period, which lasted roughly until the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), settled most of its border disputes, and attracted waves of investment. At the same time, China began an unequaled spurt of GDP growth. Productive leadership exchanges between China and other countries were common, including with Japan.

But with the onset of the global financial crisis, which coincided with the 2008 Summer Olympics, Chinese self-confidence began to overstep Deng’s hide-and-bide dictum. As the Olympic Games demonstrated China’s technical advancements and as the government’s stimulus package enabled a relatively rapid economic recovery from the financial crisis, Beijing seemed to feel emboldened or, as commonly termed, more assertive. For example, China sent a greater number of fishing and maritime administration boats into Japan’s air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the contested waters of the East China Sea for a period in early 2013. Chinese diplomats also have dragged their feet on drafting a code of conduct for the South China Sea after a promising beginning to the talks with the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea in 2002.

Admittedly, these events largely preceded Xi’s assumption of the top leadership spot of the CCP in late 2012, but he was already previously associated with a tougher approach to China’s neighbors when he led a maritime affairs small group in his capacity as China’s vice president. In this role, he oversaw China’s ingenious deployment of fishing and coast guard vessels to maintain a presence in Chinese-claimed waters and contest the claims of other countries.

China’s Road Map for Reconnecting Eurasia

One of Xi’s major moves since taking charge in 2012 has been the BRI. This endeavor is a conflation of two separately announced programs for infrastructure investment respectively known earlier as the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Twenty-First Century Maritime Silk Road. With time, these initiatives are designed to deploy China’s vast excess capacity in key materials, know-how, and capital for building infrastructure on the Eurasian continent, along the coastal waters of the Indian Ocean, and beyond; this venture is expected to total as much as $4 trillion of state-supported investment.80

Through the BRI, China is seeking to meet many needs of its neighbors for enhanced transportation, energy, and water infrastructure. Critically, Beijing also aims to continue to employ millions of its own workers and its industrial capacity in projects not only at home, where many of these needs already were met during the post–financial crisis construction boom, but also abroad. This phenomenon is not much different from the post–World War II deployment of excess U.S. capacity abroad. While it was different in nature and intent from the BRI, the historical experience of the Marshall Plan reflects that China’s economic development today bears similarities to the U.S. economy in the late 1940s.81 Likewise, at the end of Japan’s rapid postwar industrialization, its capital and corporations took up the cause of development abroad to shift from rapid industrialization to postindustrialization sources of growth at home in the 1980s. South Korea exhibited a similar phenomenon in the 1990s.

Obviously, better links between China, its neighbors, and increasingly distant markets could have the important side benefit of integrating the interests of disparate nations in productive relations with Beijing. China is a huge country with a massive population, situated sometimes uncomfortably among fourteen land neighbors, and it has conflicting territorial claims with at least three maritime neighbors. These neighboring countries are arguably more diverse than their counterparts in postwar Western Europe. China has settled most of the territorial disputes along its borders, but conspicuously it has not yet done so with India, another subcontinental power with a comparable population.

These geopolitical conditions make China susceptible to counterbalancing efforts, especially if enough of its disparate neighbors see reason for common cause. A persistent theme in Chinese foreign policy debates is that the United States is bent on organizing a coalition to contain its rise purportedly by leveraging China’s neighbors to make up for declining relative U.S. strength. The BRI is China’s best civilian tool for countering such an effort. In 2013, Xi initiated the first part of the BRI in Kazakhstan and convened a rarely held major conference on China’s relations with its neighbors. It seemed that he and his colleagues recognized that neighboring countries were perceiving China’s increased attention to sovereignty disputes as high-handed and that this approach was becoming counterproductive. Beijing needed to cushion the impact with economic incentives that were also useful at home.

U.S. actions reinforced China’s perceived need to recalibrate relations with its neighbors. In 2011 and 2012, the Obama administration promoted a rebalance to Asia, promising to redirect U.S. attention and resources from fighting terrorism in Afghanistan and Iraq. To Chinese observers, Obama and then secretary of state Hillary Clinton appeared to be attempting to forge a coalition of China’s neighbors to contain its rise. Beijing’s response was to offset the U.S. rhetorical emphasis behind the rebalance by building tighter economic links with its often-skeptical neighbors. Through the BRI and its resulting web of infrastructure, China hoped to more closely link its economy and markets with those of its neighbors, making it increasingly difficult for them to side with the United States.

Enthusiasm in China for the BRI soon reached giddy new heights, orchestrated by the CCP’s Publicity Department and facilitated by easy access to capital from the country’s policy banks. Preexisting projects in many countries were subsumed under the BRI banner to give it a sense of immediate effectiveness, to make Xi’s BRI policy sound bites seem realistic, and perhaps to clear roadblocks to approvals or credit for individual projects. In 2017, Xi presided over a BRI Forum designed to boost the initiative, a forum that brought together representatives and leaders from fifty-seven countries.82 Every administrative unit and locality in China seemed to want to get in on the deal.

International reactions to the hoopla in China have tended to reinforce the sizable expectations of the BRI that so far have outpaced its practical achievements.83 Commentators have accused Beijing of using the initiative not just to generate economic influence abroad and jobs at home but also to serve as a stalking horse for its strategic ambitions. For instance, when a white elephant port investment in Hambantota, Sri Lanka, that predated the BRI left the government unable to repay its loans to China, the port was leased, at Sri Lanka’s behest, to a Chinese operator for ninety-nine years. This outcome evoked an earlier theory that China is building around the Indian Ocean a string of pearls, or military bases for its expanding navy to exercise greater influence. Other ports and facilities elsewhere have provoked similar fears, including the port of Gwadar in Pakistan, China’s first declared overseas military base in Djibouti on the East African coast, and the Maldives.84

The U.S. Response to the Belt and Road

The United States has struggled to react constructively to the BRI. Many Chinese suspect that Washington resents that a newcomer is outspending it in a region long dominated by U.S. power and influence. The Obama administration’s early opposition to and later ambivalence about the BRI-linked, Chinese-initiated AIIB set the tone for its reaction to the broader BRI. The Trump administration has expanded on this skepticism, with former secretary of state Rex Tillerson saying that China wanted to use the BRI to “define its own rules and norms” and implicitly undermine the successful regional order largely built under U.S. leadership.85 Although the administration sent a mid-level official to attend the BRI Forum in 2017, Washington subsequently has stressed the risks to China’s partners of becoming entrapped by debt that they cannot repay, risks which presumably may make them vulnerable to Chinese pressure to do things, such as hosting military bases, they would not otherwise wish to do.

In fairness, the risk of unmanageable debt is not trivial. IMF Director Christine Lagarde has spoken publicly on this topic to China and its partners while urging them to pay attention to transparency, fiscal soundness, dispute-resolution mechanisms, and environmental impact. She also created a new institutional mechanism to manage these concerns and cooperate with China on the BRI: the China-IMF Capacity Development Center.

This approach to the BRI appears to have lessons to teach U.S. policymakers. By focusing on the potential negative effects of the initiative, Washington draws attention to itself in unflattering ways; it looks petulant, jealous, and unable to compete any longer. The United States would do better to take a more constructive approach. After all, BRI investment in Central Asia, for example, may help meet common U.S. and Chinese goals, such as offering productive employment to youth as an alternative to Islamic fundamentalism, promoting commerce in impoverished areas, stabilizing the region, and offsetting Russian influence.

A more constructive U.S. approach to the BRI would center on the following five principles:

- Avoid lecturing participating countries about the risks of the BRI and show respect for their own judgment about how to proceed. There is already resistance to the excesses of the BRI emerging in India, Malaysia, Pakistan, and Thailand. In time, China will have to adjust to these nations’ preferences and laws.

- Discourage U.S. governmental participation in the BRI. The internal complexities of China’s BRI finance and contracting arrangements have a logic of their own. However, the U.S. government should not interfere with and, where possible, it should promote private-sector involvement. U.S. firms do not have much to teach China about railroad construction these days, but their financial, consulting, and technical services may have a role to play.

- Refrain from exaggerating the degree of geopolitical influence that China will likely gain from the BRI, but avoid ignoring it too. Beijing’s neighbors have little interest in taking on the so-called Chinese characteristics that the initiative promotes. If China squeezes them too hard, they will seek to bandwagon with friends, a form of balancing that the United States should welcome.

- Learn lessons from China’s BRI failures rather than gloat over them. There is already evidence that in various ways China and its partners are trying to correct mistakes they have made. Helping them do so is in the longer-term U.S. interest because these projects may help achieve objectives that Beijing and Washington do have in common, such as stable societies with employment opportunities and the potential to grow markets for U.S. products.

- Resist the temptation to create an alternative to every proposed Chinese project, thus forcing countries that need help to choose between China and the United States (and its allies). For example, Japan’s generous offers of infrastructure financing, with supplements through the new U.S. Trade and Finance Initiative (as embodied in the BUILD Act), should not be made on an either/or basis, but as a complementary way of providing long-term benefits to the economies concerned.

How Washington and Regional Partners Can Manage China’s Rise

By virtue of its existing network of alliances and friendships, the United States enjoys a huge advantage over China in the Asia Pacific. Habits of cooperation in the region have long been institutionalized, even if they are occasionally affected by day-to-day events. The United States enjoys a large endowment of relevant military equipment and experience in the region as well. The accumulated stockpile of ships, aircraft, bases, and relevant experience is considerable, though naturally some of these assets are in need of updating. It is worthwhile to consider Washington’s relationships with several key regional partners in turn.

Japan

Japan is the most consequential U.S. ally in the Asia Pacific due to its geographic location, robust economy, advanced industries, common values, professional military, and extensive basing facilities. It sits astride vital maritime straits. In some respects, these features can also be viewed as vulnerabilities: Japanese cities could be crippled by targeted enemy attacks on critical infrastructure. Likewise, some of these bases could be rendered ineffective by conventional missile attacks, and surface ships could be sunk.

The central issue for policymakers is how to diminish Japan’s vulnerabilities while enhancing its strengths. Allied force modernization is occurring at a measured pace that seems set to eventually fall behind that of China’s forces quantitatively if not yet qualitatively. Tokyo has been making modest efforts to redeploy forces and weapon systems from the north, where Japan long faced the Soviet Union, to the southern end of the archipelago, where China is increasingly active. In addition, Japan is developing small, flat-topped naval vessels that can accommodate F-35 short takeoff and vertical landing aircraft, vessels that could potentially be used as improvised aircraft carriers, increasing the number of threats and targets potential adversaries would have to anticipate.

In an era of modern missile technology, the resiliency to absorb attacks is a major consideration. Reducing the risks associated with single-point-of-failure targets on Japanese military bases, such as above-ground fuel storage, is another objective for adapting to the region’s changing security environment. Additionally, increasing the size of the U.S. and Japanese sub-surface fleets as well as increasing deployments of unmanned aerial vehicles would help stabilize Japan’s security environment at a manageable cost.

Under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Japan has been an active foreign policy player. The country has allocated resources to offer many countries an alternative to China’s BRI. Moreover, Tokyo supports the Trump administration’s efforts to bolster cooperation among Australia, India, Japan, and the United States in a Quadrilateral Security Dialogue intended to promote their common values and interests in contrast with those of China.

But as a reflection of geographic realities, Abe has shrewdly kept doors open to Beijing and Moscow despite the blows to diplomatic relations inflicted by China’s interference in the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and Russia’s annexation of Crimea. In 2018, which marked the forty-fifth anniversary of Japan’s establishment of diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China, Tokyo resumed high-level diplomacy with Beijing after eight largely unproductive years. Meanwhile, Japan is offering to provide assistance to Russian healthcare and social welfare projects, according to interviews with senior Japanese officials.86

Economically speaking, in March 2018, Japan performed an important, but unacknowledged, service to the United States by helping conclude a successor trade agreement to the TPP (the CPTPP-11); this successor agreement among the original treaty’s other eleven parties followed the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the TPP. While the absence of the United States significantly reduced the eventual agreement’s scope, this agreement does keep alive the prospect that Washington may reconsider its withdrawal at a later date and revisit a comprehensive approach to its economic role in the region. Such an outcome would remove most of the trade frictions that in the past have bedeviled U.S.-Japanese relations. This, in turn, would further strengthen the political climate surrounding the alliance. Eventually joining this agreement would permit the United States to resume leadership of a cohesive economic bloc that, in terms of competing for support in the region, would offer advantages over China’s more limited economic vision.