Official development assistance (ODA) is one of the primary ways low- and middle-income countries across the world, including in Africa, receive development financing. The largest donors of these ODA funds come from the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), which includes thirty-two mostly high-income countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany. One of the notable global financial trends of 2024 seems to be a reduction, by several DAC countries, in bilateral ODA.

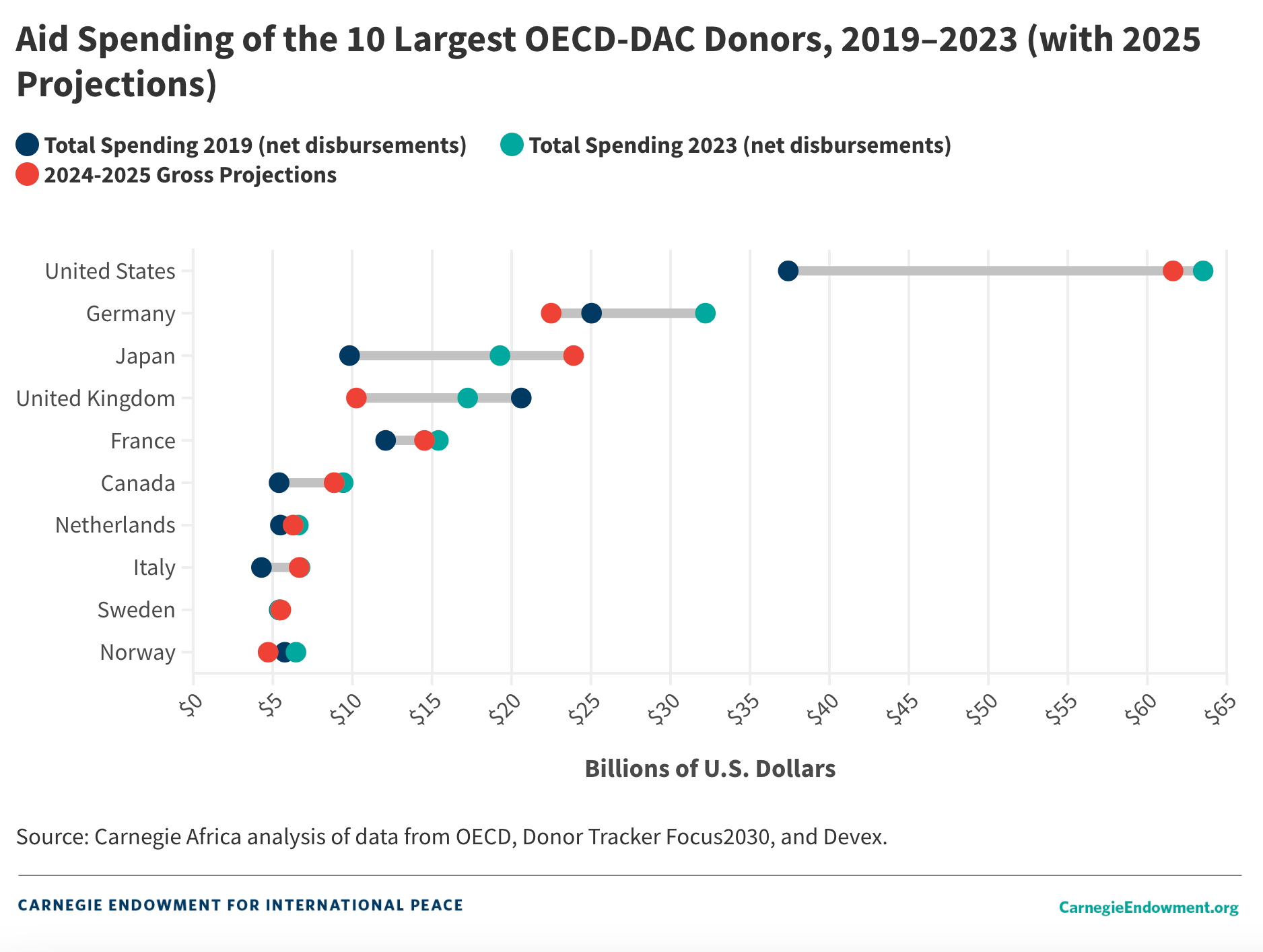

Over the past five years, ODA has broadly increased. This trend has coincided with a general decline in Chinese concessional loans. In 2024, however, this dynamic seems to be reversing. While China does not provide as much developmental assistance in the form of grants as the DAC does, recent Chinese commitments have aimed at increasing loan provision. At the same time, the top ten DAC donors have significantly decreased their ODA development spending from 2023, as the figure below shows.

Specifically, across Africa and Asia, DAC donors have decreased their ODA flows since the pandemic. In an effort to fulfill domestic budgetary goals, countries like the United States, which slashed over $2 billion in aid funding, have targeted ODA. In its overall budgets between 2022 and 2025, Germany, the second-largest ODA provider, has cut over €4.8 billion ($5.3 billion) of its core development and humanitarian assistance. Similar deductions to 2024–2025 ODA budgets have come from other countries such as France (which cut over $1 billion) and the United Kingdom (which cut over $900 million).

In several cases, these bilateral ODA budget cuts will take these donors further from their pledges to devote 0.7 percent of their gross national income (GNI) to aid spending. This 0.7 percent target was adopted in a United Nations (UN) resolution in 1970, based on a Pearson Commission report. Yet even fifty years after its adoption, most DAC countries that agreed to the target have not reached this annual goal. There are a few members, particularly Nordic countries, that have met or even exceeded the 0.7 percent target. As of 2023, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reports that Norway (1.09 percent), Luxembourg (0.99 percent), and Sweden (0.91 percent) have all well exceeded the goal and Germany (0.79 percent) and Denmark (0.74 percent) have sufficiently met it. In contrast, countries like the United States, United Kingdom, and France are moving further away from this goal in cutting their budgets.

Since 2020, bilateral aid flows among the top donors to the most vulnerable parts of the world have fluctuated and are now beginning to decline. Aid to developing regions has decreased while spending on refugees and aid to Ukraine have encompassed a greater proportion of global ODA funds. In 2021, ODA for developing countries decreased by 2 percent, falling more significantly by over 3.5 percent for countries in Africa, Asia, and Oceania. In 2023, DAC members devoted an average of just 0.37 percent of their GNI to ODA. This is grossly below the 0.7 percent target set by the 1970 resolution, and these numbers are expected to decrease again in the next year. These reductions come at a time of international emergency as the spread of Mpox overwhelms parts of Africa and humanitarian crises create mass food insecurity.

In parallel, China has reaffirmed and increased its commitment to financing development projects in Africa. During the 2024 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), President Xi Jinping made a public commitment to contribute $50 billion to African economic and infrastructure development over the next three years. While not directly comparable to ODA from DAC countries, this commitment represents a $10 billion increase from the last FOCAC commitment in 2021. China is also emerging as a prominent lender in last-resort funding, providing emergency liquidity support to countries in debt distress. The People’s Bank of China has entered into various currency swap agreements and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank has added more prospective African members, including Togo and Kenya. A global reduction in bilateral ODA flows could push African governments to seek out high-interest loans, which may result in more funding gaps for Africa.

During FOCAC 2024, UN Secretary-General António Guterres called the debt situation for African countries “unsustainable and a recipe for social unrest.” If the UN annual ODA goal continues to be constrained by domestic budgetary goals, there could be serious consequences for the financing of global development.

.jpg)