This publication is a product of Carnegie China. For more work by Carnegie China, click here.

The engagement era of the U.S.-China relationship that began in the 1970s was transformative not only for the two powers, but also for the Asia-Pacific region. Both Japan and Australia took quick actions to establish diplomatic relations with China in the wake of former U.S. president Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China. In Southeast Asia, partly influenced by Washington’s rapprochement with Beijing and partly driven by their own national interests, countries that were strongly suspicious of the communist China (such as Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines) rushed to establish diplomatic relations with China, while others (such as Singapore) reconnected with China but took longer to establish diplomatic ties. Engagement, to a large extent, was not only a U.S. policy, but a policy shared by all these countries.

Today, the engagement policy with China is basically dead in the United States, but in Southeast Asia, it remains an active pursuit and default option. Moreover, the idea of engagement in Southeast Asia is not just about Beijing. It is also about keeping Washington active in the region and encouraging at least a minimal level of cooperation between the United States and China.

ASEAN’s 2021 Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with China upgraded the Strategic Partnership first established in 2003, while regional countries have formed varying degrees of bilateral strategic partnership with China over the same period. Both ASEAN and China are strong supporters of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, while negotiations on the upgrade of ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement are taking place. Signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects in Southeast Asia, such as the China-Laos Railway, Bandung-Jakarta High Speed Rail, and East Coast Rail Link in Malaysia, are all progressing, if not completed and operational. In 2023, except for Myanmar and Brunei, the leaders of ASEAN member states all visited China; leaders from Cambodia, Indonesia, and Malaysia did so twice. Vietnam also became the eighth country in Southeast Asia to agree with China on the latter’s formulation of “Community of Shared Future,” following President Xi Jinping’s visit in December.

All these developments are signs that engagement with China is still quite alive in Southeast Asia—but not without at least some level of reservations, concerns, and apprehensions. This is especially true for the maritime Southeast Asian countries embroiled in the South China Sea disputes with China that have felt the deleterious and pressuring effects of China’s imposing actions. They will remain careful in their engagement. The Philippines, in particular, have taken a sharp turn after years of engagement efforts with China under the administration of former president Rodrigo Duterte. The persistent tensions between China and the Philippines in much of 2023 are a reminder that engagement will not always be as effective as assumed.

Engaging with China and with the United States are not zero-sum choices for Southeast Asia, but the challenge for the region’s leaders and diplomats is actually about keeping the United States interested in the region. Southeast Asia has seen how the more actively engaging presidency of Barack Obama was replaced by the administration of President Donald Trump that showed little interest in bilateral or multilateral relationships, other than as places to meet with the North Korean leader Kim Jung Un. President Joe Biden’s administration has a greater appreciation for the strategic position of Southeast Asia in the wider Indo-Pacific framework and its strategic competition with China, and it has adopted a more concerted and integrated approach in fostering the United States’s relations with Southeast Asia. In addition, Southeast Asia is a key front of the U.S.-China technological rivalry, with a major role to play in the movement of reshaping of and derisking regional and global supply chains.

Under the Biden administration, a special U.S.-ASEAN Summit was held in May 2022, and in November 2022, the United States and ASEAN also upgraded their relationship to the level of Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. Within a year, a number of initiatives covering foreign assistance, digital economy, infrastructure and connectivity, public health, education, and maritime and defense cooperation with ASEAN were undertaken by the U.S. government. These are all welcomed moves for Southeast Asia, but whether the United States will sustain in its engagement is uncertain. The decision by Biden not to attend the ASEAN Summit in Jakarta in September 2023 was a disappointment, and the 2024 U.S. presidential election could see the return of Trump. In addition, at the bilateral level, the United States seems to practice selective engagement that prioritizes countries that are often seen as more strategic or valuable in its competition with China. Countries that would not get as much engagement and commitment certainly would not be impressed.

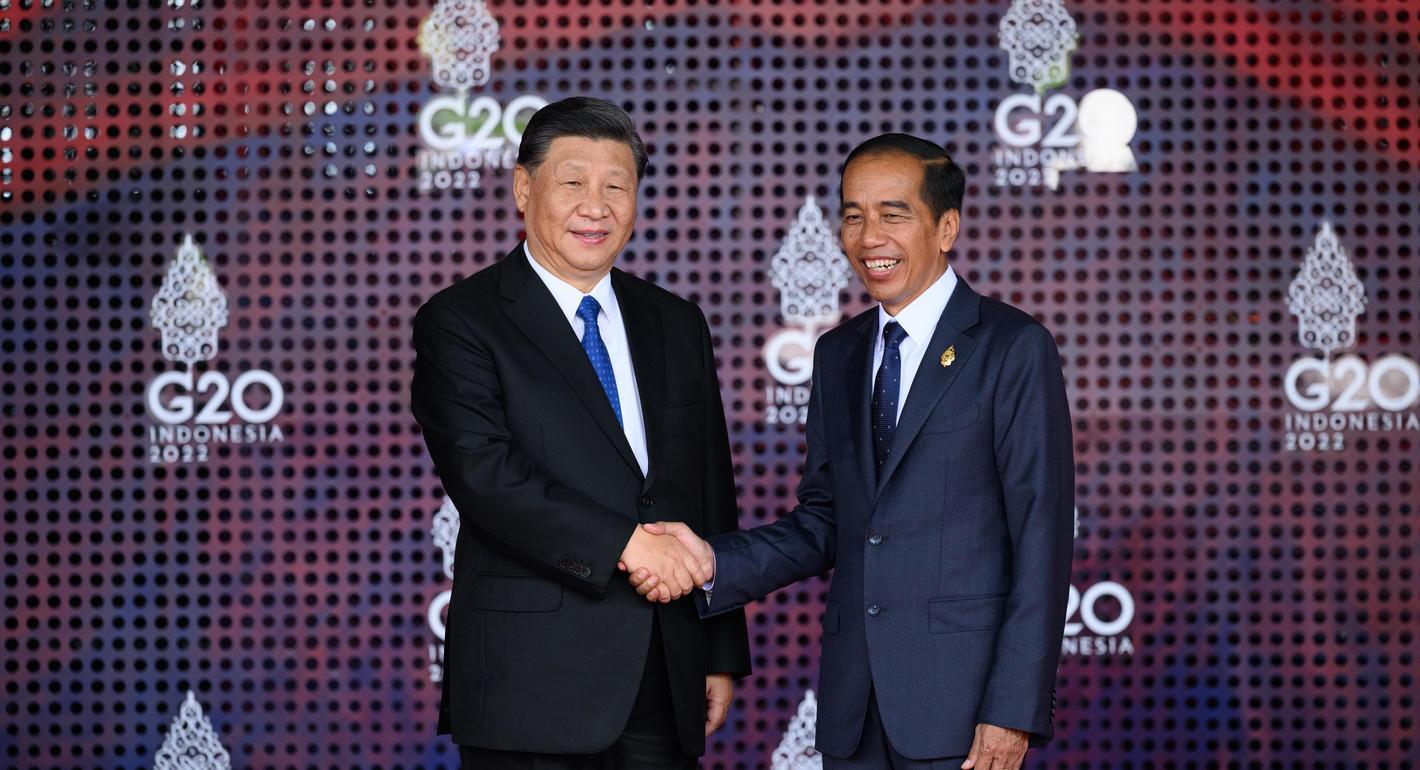

Finally, Southeast Asia has a stake in the stabilization of U.S.-China relations. U.S.-China strategic competition has brought economic benefits to Southeast Asia, largely as investments that would have gone to or stayed in China. But fundamentally, the polarization between the two powers is not a welcomed trend. In the China-hosted Bo’ao Forum in March 2023, Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim warned against the consequences of the growing rivalry. At the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore in June, Singapore Defense Minister Ng Eng Hen highlighted the worrying “declining touch points between the American and Chinese military establishments” and urged the resumption of communication channels. Southeast Asia regional leaders were encouraged when Washington and Beijing restarted some levels of engagement toward the end of 2023, with the mutual visits of high-level officials and the summit between Xi and Biden in San Francisco. The region will be keen to sustain this progress in the years to come, even though it was starting from a very low base, with a long road ahead.

All in all, keeping the United States and China engaged will remain the preferred approach for Southeast Asian countries, but whether the region can play a more proactive role in shaping the dynamics of the U.S.-China rivalry in the region will depend on the resilience and strengths of individual states, their collective coherence in the form of ASEAN, and the visions and strategic wisdom of the regional leaders.