As COP28 approaches, Pacific Island officials are working to secure marine health while promoting the resilience of Blue Economy industries, such as coastal fisheries. Earlier this month, the Pacific Islands Forum meeting centered discussions on the ocean as a collective resource and cultural identity. But a new development is causing tension between economic growth and ocean protection efforts: deep-sea mining.

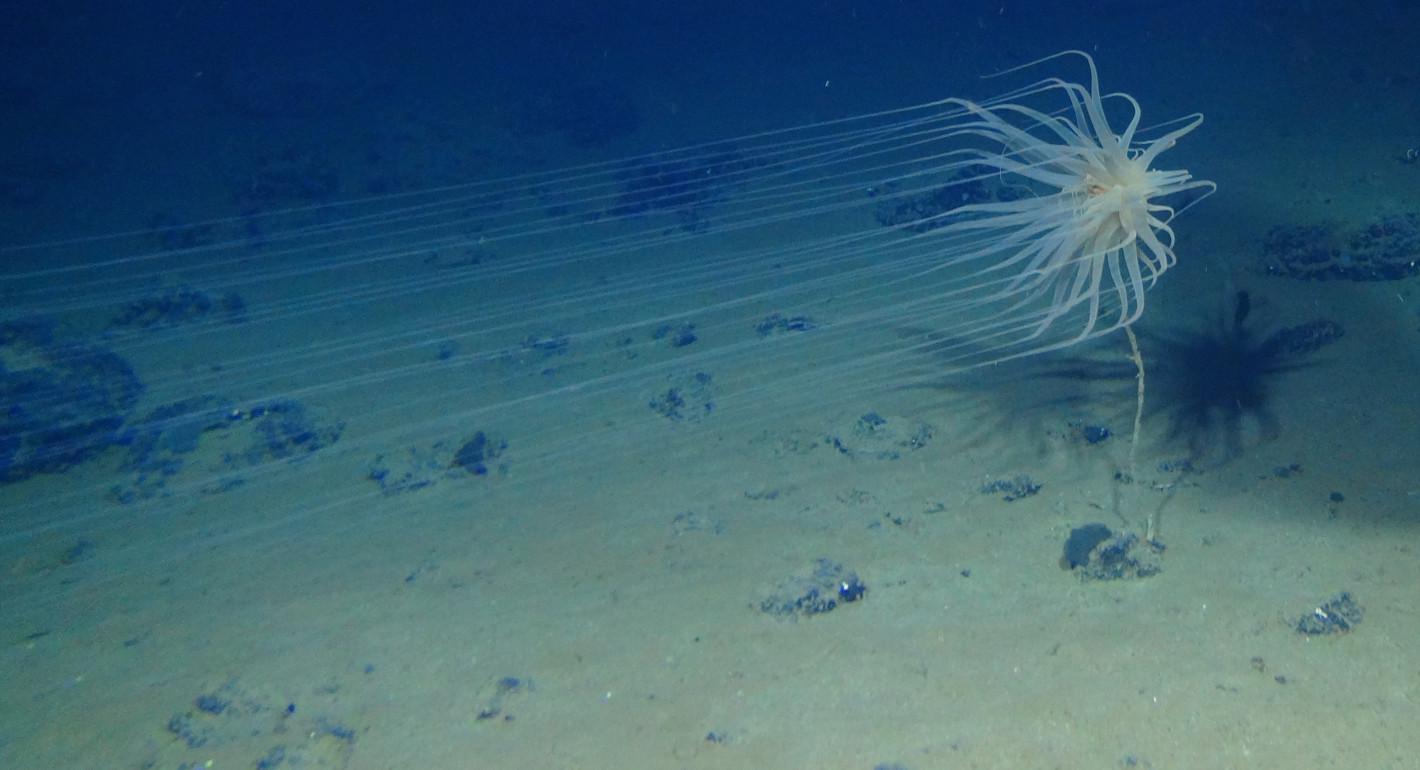

Deep-sea mining is a catchall term for three methods of mineral extraction, the most common being the removal of underwater rocks known as polymetallic nodules. These nodules contain cobalt, nickel, and manganese—essential ingredients for clean energy technologies such as electric car batteries. The discovery of these nodules has initiated a race to the sea floor as high-income countries clammer for underwater minerals needed for the global transition from fossil fuels to clean energy.

Countries that control critical minerals will govern the political economy of electrification and decarbonization. At present, 70 percent of the mined supply of global cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and 95 percent of global lithium is from Argentina, Chile, and China. The concentration of minerals in a handful of states grants disproportionate power to mineral-rich countries and leaves global supply chains vulnerable to choke points. Deep-sea mining could offer mineral-poor states the opportunity to secure supply chain independence and access emerging green technology markets.

Much of deep-sea mining extraction will play out in the Pacific. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone, located in the Pacific Ocean, has one of the largest known clusters of deep-sea minerals. The International Seabed Authority (ISA), an independent governing body created by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, has issued thirty-one permits to twenty-two contractors for deep-sea mining exploration. Seventeen of these exploratory permits have been issued for the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

But for Pacific Island states dependent on Blue Economy sectors such as fishing, tourism, and renewable energy for their survival, the consequences of deep-sea mining in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone are understudied and of great concern. The harms of deep-sea mining on migratory fish patterns, marine biodiversity, and long-term ecosystem health are unknown and may be immediate and irreversible. One study found evidence of ecosystem disruption twenty-six years after a disturbance and recolonization experiment that mimicked deep-sea mining.

Until comprehensive regulations that safeguard both the political and physical environments from exploitation can be integrated into ISA extraction protocols, a precautionary deep-sea mining moratorium should be implemented until 2030. The moratorium would grant the UN Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization enough time to consolidate global research findings through the Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development campaign and achieve its goal of mapping 80 percent of the seabed floor by 2030. This mapping would provide a better understanding of deep-sea ecosystems and the potential impact of mining operations.

Prior to the approval of any mining projects (with or without a moratorium), the ISA must issue a series of regulations guided by three principles.

First, Pacific Island states must be viewed as legitimate actors in the deep-sea mining conversation. Accordingly, countries such as Nauru, Cook Islands, and Tonga that are likely to proceed with deep-sea mining must be able to develop the capabilities to negotiate commercial contracts and provide technical oversight to mining operations. In addition, states opposed to deep-sea mining projects must not be harmed, directly or indirectly, by Pacific operations.

Second, environmental protection provisions must be strong and highly credible. The world cannot, at this stage of the climate crisis, take an uncalculated risk with the ocean. Safeguards must be based on continued deep-sea research, pioneered by campaigns such as the Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. Building on this data, the ISA must provide guidelines on appropriate technology to be used in the extraction process as well as issue prohibition protocols that ban certain practices in sensitive areas. Until further research on the long-term impacts of deep-sea mining has been conducted, no mining projects should be initiated.

Last, the Pacific Islands Forum—a coalition of eighteen states invested in regional prosperity—should possess safeguards that extend beyond the ISA process. While the ISA would issue extraction permits, the Pacific Islands Forum should maintain a suspension protocol as an independent regulatory mechanism. To build a regional consensus on this divisive issue and protect Pacific voices, Pacific Island states should have the right to halt deep-sea mining projects if they believe ISA oversight has failed. Guaranteeing island states the right to press pause would grant them the ability to petition for scientific evaluation and prevent the region from being captured by foreign mining interests.

The irony of the green energy transition is that industry will need critical minerals, such as cobalt and manganese, to successfully decarbonize, but extraction—both on land and in the ocean—involves environmental degradation. Some argue that deep-sea mining is a better alternative to terrestrial mining, as it does not generate harmful waste by-products. However, using today’s technologies, the deep-sea extraction process will generate plumes of disturbed sediment that will disrupt local ecosystems—about which we know very little.

Attitudes toward the deep sea are currently driven by commerce and industry—leaving the region ripe for exploitation. A concern for many Pacific states is that deep-sea mining in the Blue Pacific will become a new theater of resource conflict as high-income states descend on identified clusters of polymetallic nodules. While materials found in the high seas are supposed to be global goods that benefit humankind, historical inequities, like environmental and community degradation, may persist. As such, the ISA is likely to find itself between many rocks and many hard places as it constructs climate conscious regulations that protect Pacific Island countries from mining harm. However, by affirming the power of Pacific Island voices, developing UN-informed environmental protections, and offering a suspension protocol to states of the Pacific Islands Forum, the ISA may be able to navigate these murky waters.