ECONOMY

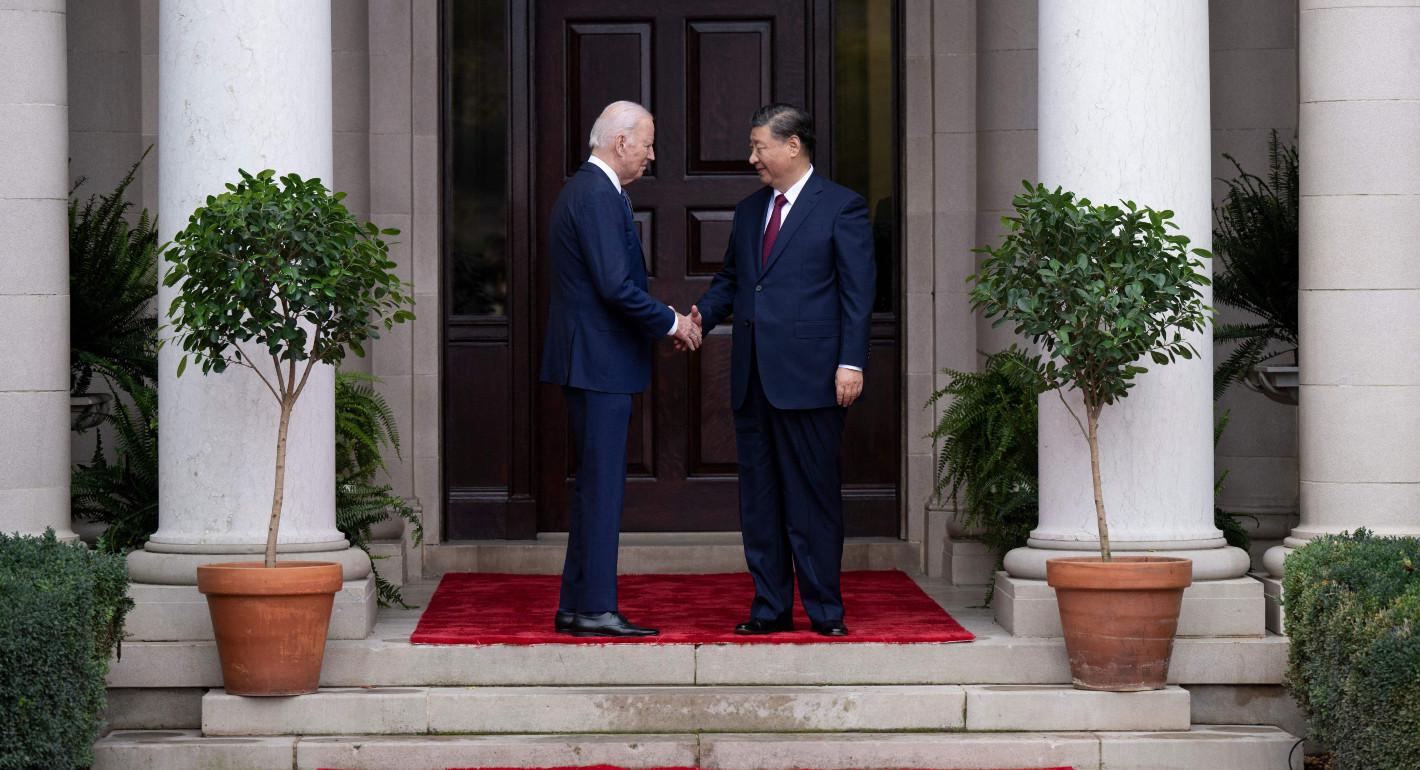

Presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping both viewed their bilateral summit, adjacent to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting, as an opportunity to prevent a competitive relationship from spiraling into a more contentious confrontation. For Xi, the meeting was also an opportunity to enhance his status at home, which has been weakened by a disappointing post-pandemic economic recovery.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen had earlier noted that the Biden administration was not interested in economic decoupling but was focused on a narrower set of restrictions geared to national security. The administration’s credibility, however, has been undermined by a variety of punitive actions, such as leaving intact the previous administration’s tariffs. That U.S. trade and investment flows with China have declined sharply relative to other trading partners is seen by Beijing as evidence that Washington’s intentions go well beyond normal security concerns.

Beijing’s response to Washington’s punitive measures have been limited mostly to creating a domestic manufacturing capacity for high-tech products that the United States will no longer supply and deepening China’s trade links with other nations. Xi reiterated China’s support for more open trade policies rather than protectionism and noted that the world “is big enough for the two countries to succeed.” He also pressed Biden to lift export controls for sensitive equipment and support stronger bilateral financial and investment links.

Biden, however, cannot afford to appear conciliatory, given the anti-China sentiments of both Republicans and Democrats. He noted U.S. support for a free and open Indo-Pacific, aspects of which Beijing views as a containment strategy. In his press conference, Biden was careful to characterize the discussions as candid and constructive, and in response to a question, he once again described the Chinese leader as a “dictator.”

From the White House’s perspective, the most successful outcome of the discussions was Beijing’s commitment to curb trade in fentanyl-related ingredients and resumption of a military-to-military dialogue—on top of a renewed program of climate change initiatives. Both sides were also keen to reset relations and establish stronger lines of communication. Otherwise, the economic outcomes were largely in the form of symbolic adjustments—extensions of ongoing economic and technological consultations, improved air travel links, and managing risks of oversupply in green technology products—with assurances from both sides of not letting the relationship deteriorate any further.

—Yukon Huang

MILITARY

The resumption of some U.S.-China military-to-military dialogues met the rather minimal expectations for Wednesday’s summit. Both Beijing and Washington pledged to reinstate paused defense policy coordination talks, military maritime consultation meetings, and direct telephone links between operational commanders. None of these channels is new, and none is sufficient to meaningfully mitigate growing military tension between the two countries.

Historically, Beijing has withheld defense contacts to express its displeasure at U.S. actions in other facets of the relationship. Resuming these activities is then dangled as a “concession” and traded off against other political objectives—and that is precisely the pattern witnessed in San Francisco this week. Defense contact was last suspended in August 2022, and a series of senior-level dialogues were “refused, cancelled, or ignored” since then, according to the Pentagon. This is in keeping with a long pattern of on-again, off-again, bilateral military dialogue.

Reestablishment of these links is nonetheless a welcome step. It is especially welcome for the international leaders assembled for APEC who would like to see responsible, constructive statesmanship between the two great powers, not a further slide toward catastrophic conflict. The restoration of these minimal lines of communication, however, is only likely to buy down a small part of the risk on the far margins of increasingly tense U.S.-China military interactions in the Western Pacific.

Biden stressed that these measures would promote improved communication because “that’s how accidents happen.” The U.S. and China are indeed now operating in close proximity across the Western Pacific, where close, potentially dangerous encounters among military aircraft and ships have become routine. Renewed consultations and phone calls may well reduce the likelihood of unintentional escalation, but it is the intentional variety that remains well beyond these old dialogue mechanisms.

Even if the People’s Liberation Army picks up the phone in a crisis—a heroic assumption, given past practice—the strategic interests (and corresponding military postures) of each nation present a structural dilemma that words will not easily overcome. Washington remains committed to free navigation in the region and a long-term policy to “fly, sail, and operate wherever international law allows.” Beijing claims that nearly all of the sea and air space along its periphery is under its jurisdiction, ambiguously fenced off from what “international law allows.” These hardening, perhaps incompatible, positions mean that another major incident such as the 2001 EP-3 collision would be nearly impossible to deescalate.

—Isaac Kardon

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

The Biden-Xi summit produced a modest deliverable on AI: an agreement to set up formal government-to-government discussions on the technology. Details on the form or substance of those discussions were not made clear. The White House readout stated that the two leaders “affirmed the need to address the risks of advanced AI systems and improve AI safety through U.S.-China government talks.” The Chinese statement was more vague, listing AI alongside issues such as counter-narcotics where the governments should cooperate through existing or new government channels. To make the most of this outcome, Washington will need to keep two tactics in mind.

First, the United States will need to keep track of the domestic bureaucratic politics of AI governance in China. Different Chinese ministries and agencies are pushing different approaches to AI regulation, and the top leadership has sent mixed messages on which of these groups will lead in China’s international engagement on the issue. The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) has taken the lead on writing domestic regulations and creating regulatory tools and standards. The CAC was also the lead author on China’s Global AI Governance Initiative, announced by Xi at the Belt and Road Forum. But in other contexts the Ministry of Science and Technology has stepped up, including by leading the Chinese delegation to the UK’s recent AI Safety Summit. These two parts of the Chinese bureaucracy have different capabilities and concerns when it comes to AI, and when engaging in these dialogues, the United States needs to be clear on the institutional interests and capabilities of each counterpart.

Second, instead of aiming primarily for formal, binding agreements between the countries, Washington should first prioritize mutual awareness and exchanges of best practices. When it comes to ensuring that powerful AI systems are built safely, domestic regulations in both China and the United States are likely to matter more than any bilateral or international agreements. International agreements on AI risks—such as the recently signed Bletchley Declaration—hold powerful symbolic import, and they can mobilize resources to advance our scientific understanding of AI risks. But when it comes to operationalizing the results of that understanding, each country will likely do that through their own regulations. The recent White House executive order on AI, as well as the regulations and technical standards emerging from China, constitute the hard constraints that are changing how AI models are built in both countries. For the time being, the two countries should focus on understanding the nature of those constraints in the other country and exchanging best practices on technical and policy interventions for the safe deployment of AI.

The world is at a key moment in AI governance—a time when scientists and policymakers in both countries are still trying to figure out how best to approach regulating this technology. It’s during these times of policy plasticity that dialogue—done strategically and with realistic goals—can have the greatest impact on shaping the safe and productive deployment of AI around the world.

—Matt Sheehan

.jpg)