China’s approach to the Ukraine war has been somewhat puzzling. Beijing has alternated between allowing and censoring pro-Ukraine posts on Chinese internet platforms and emphasizing and de-emphasizing its diplomatic alignment with Russia. But more than a month into the conflict, the distinct contours of China’s policy are coming into focus. Beijing’s initial straddling strategy, wherein it attempted to maintain its strategic partnership with Russia, defend the sanctity of territorial integrity, and minimize its exposure to Western sanctions, has evolved into an approach that differentiates among domestic propaganda, international diplomatic rhetoric, and limited, or symbolic, actions.

In terms of domestic propaganda, China has begun to more stridently support Russia over the past few weeks. Chinese state-backed media, such as PLA Daily and People’s Daily, have published screeds blaming NATO’s eastward expansion for the war, completely exculpating Russia in the process. Foreign Minister Wang Yi publicly criticized the United States for ignoring Russia’s legitimate security concerns, while Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng condemned NATO for provoking Russian aggression.

Despite its increasingly aggressive propaganda at home, China has, through international diplomatic rhetoric, emphasized its interest in peacefully resolving the conflict. Though unwilling to take an active role in mediation, Beijing has repeatedly called for negotiations between Kyiv and Moscow. During his recent call with U.S. President Joe Biden, Chinese President Xi Jinping noted his “priority is to keep the dialogue and negotiations going . . . and cease hostilities as soon as possible.”

In terms of actions, China has fallen short of meaningfully supporting Russia. Despite its stated disapproval of Western sanctions on Moscow, Beijing has clearly signaled it does not want to run afoul of these economic embargos. China’s decision not to provide Russia with airplane parts is in keeping with this strategy. Beijing has reportedly not assisted Moscow with military support, despite concerns it was considering doing so. Chinese energy firms, wary of sanctions, have paused projects in Russia, while the China-dominated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and Shanghai-based New Development Bank suspended initiatives in the country.

But these three seemingly incongruous approaches signal the motivations behind China’s evolving position on Ukraine. In short, China is aiming to accomplish five goals: manage public opinion at home, provide Russia with rhetorical support, signal to Asian countries the danger of NATO-like structures in the Indo-Pacific, appear to be a responsible stakeholder in the broader international community by calling for negotiations, and limit the damage to its economic ties with the United States and Europe.

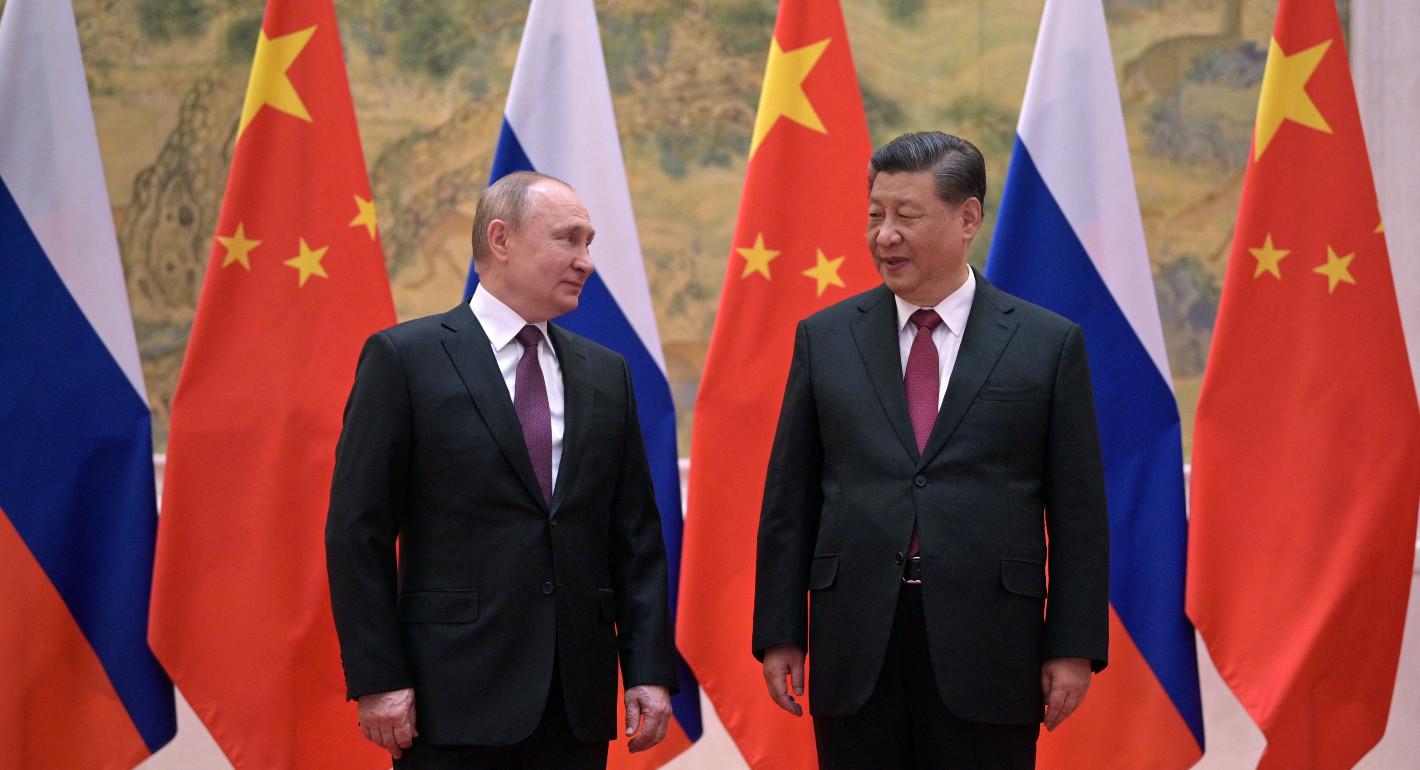

First, China’s pro-Russia, anti-U.S., and anti-NATO rhetoric is principally aimed at the Chinese domestic audience. Senior Communist Party leaders have determined that this type of messaging is crucial to maintaining domestic support for Russia, given Xi’s embrace of Russian President Vladimir Putin during their February 4 meeting. Furthermore, the party likely calculates that criticizing the United States helps justify Russia’s actions, and China’s pro-Russia expressions and parroting of Russian state media talking points are also aimed at reassuring Moscow in the absence of significant material support.

But China’s rhetoric is also aimed at the rest of Asia. Wang has claimed that the Quad is a NATO-like organization designed to counter China’s growing influence. By making the case that NATO expansion caused the Ukraine conflict, China is carefully warning its neighbors that the creation or growth of minilateral or multilateral security groupings could bring violence to the Indo-Pacific.

Next, Beijing’s diplomatic statements and actions are in line with most experts’ beliefs that China does not wish to see the war continue. China is a somewhat inexperienced global diplomatic power, focused mostly on its own narrow core interests. Xi appears more comfortable rhetorically calling for diplomacy rather than having China play a leading role in any mediation effort. China’s position is further complicated by the fact that Wang and Le, two of its top three diplomats, have been less than diplomatic in their blaming the United States and NATO for the conflict. China’s diplomatic rhetoric is also targeted at Europe, as Beijing wants to appear helpful while working to revive the stalled Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with Brussels, which would greatly strengthen China-EU economic and business ties.

Last, China’s reluctance to materially support Russia in contravention of sanctions is a clear acknowledgment of the enduring importance China places on its commercial ties with the West. Beijing is eager to maintain its significant economic linkages with the United States and Europe in the face of its economic slowdown; increasingly serious countrywide coronavirus outbreak; and global energy, commodity, and food price hikes. That being said, China will likely continue to bolster trade in nonsanctioned goods and services with Moscow, as well as provide limited support to Russia’s decimated financial industry, albeit in a way that avoids triggering Western secondary sanctions. It is unclear, however, how much increased economic ties can really help Russia.

China clearly believes that its contradictory rhetorical, diplomatic, and material approaches to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine provide it the best opportunity to protect its interests. Though neglecting to flagrantly violate sanctions could help China forestall an economic conflict with Washington and Brussels, Beijing thus far has not won any new American or European friends. It could also end up straining ties with Putin, though China may believe Russia too weak at this point to necessitate changing course.

Though many have pointed out the inconsistencies in China’s delicate balancing act, Beijing has yet to suffer anything worse than reputational damage. Senior Chinese leaders would likely view any other course of action as much more deleterious to the country’s interests. Violating sanctions to aid Russia would bring economic calamity, while pressuring Russia to end the war could make Xi look bad. Though Beijing’s position appears untenable, the party likely views it as the least bad of a suite of terrible choices.