Source: Conversation

Russians will head to the polls in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic between June 25 and July 1 for a national referendum on changes to the country’s constitution. Ahead of the poll, our initial findings from an ongoing survey of 3,000 young, urban Russians found they associate the referendum primarily with the social guarantees that are also being promised, such as a minimum wage, rather than changes to the country’s political structure, notably the presidency.

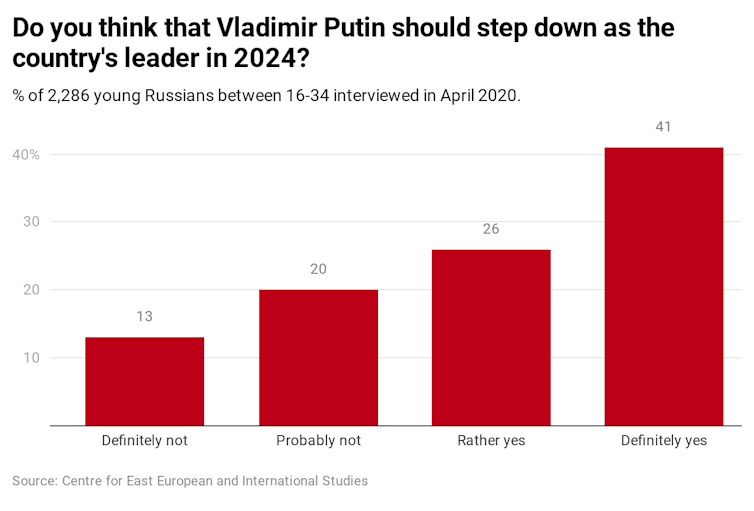

Asked whether Vladimir Putin should step back from any leadership position, more than two-thirds of our respondents think that he should.

The total number of COVID-19 infections in Russia is the third highest in the world after the US and Brazil. According to official Russian statistics, the absolute number of cases continues to increase steadily. A belated but very strict lockdown has now been lifted in order to generate a feelgood atmosphere ahead of a military Victory Parade on June 24 and the week-long referendum on far-reaching constitutional reforms, which had originally been scheduled for April 22.The military parade, originally scheduled for May 9, will mark the 75th anniversary of victory over Nazi Germany, which occupies a central place in the state’s identity discourse. Both the parade and referendum have become critical tools for President Vladimir Putin to shore up his declining popularity ratings.

According to a poll by the independent agency Levada in April, Putin’s popularity dropped below 60% for the first time since he assumed office. While that’s still a high percentage by western comparisons, it’s a warning signal in an authoritarian system. A subsequent poll in May asked respondents to name politicians they trust. Only 25% chose Putin, which is his lowest rating, although still higher than that of other politicians.

The plebiscite was meant to add public approval from below to the constitutional amendments from above, which were railroaded through by Putin in the first few months of 2020. The amendments give Putin different options for when his current term in office ends in 2024, and also include a new clause giving all presidents immunity after leaving office. For now, Putin has made it clear that he will remain at the heart of Russian politics. He could either do this by staying on as president based on a tailor-made amendment allowing him to serve for up to two further terms, or by standing down and taking on less direct responsibility – but continuing influence – as the head of the State Council.

Putin embarked on the path of constitutional reform in response to a diffuse societal wish for change. This has become evident in opinion polls and in frequent smaller protests about the mismanagement of local issues, but has not yet crystallised into a concrete political alternative.

What young Russians think

As part of a series of online surveys conducted by the Centre for East European and International Studies, which we’re also both affiliated to, we’ve been investigating how young Russians think about the constitutional reform process and to Putin himself.

Youth has played an important role in Russian politics in recent years. The Kremlin continues to actively mobilise the loyalty of young people through patriotic education and militaristic youth movements, such as Yunarmiya. But young Russians have also been very visible during social and political protests.

Following annual online surveys conducted in 2018 and 2019, in mid-April 2020 – just before the referendum was postponed – we reached 3,000 young Russians aged 16-34 for the 2020 round of our survey. The respondents were based mainly in Russia’s largest cities with over one million inhabitants but also smaller cities from about 250,000 inhabitants from across the country.

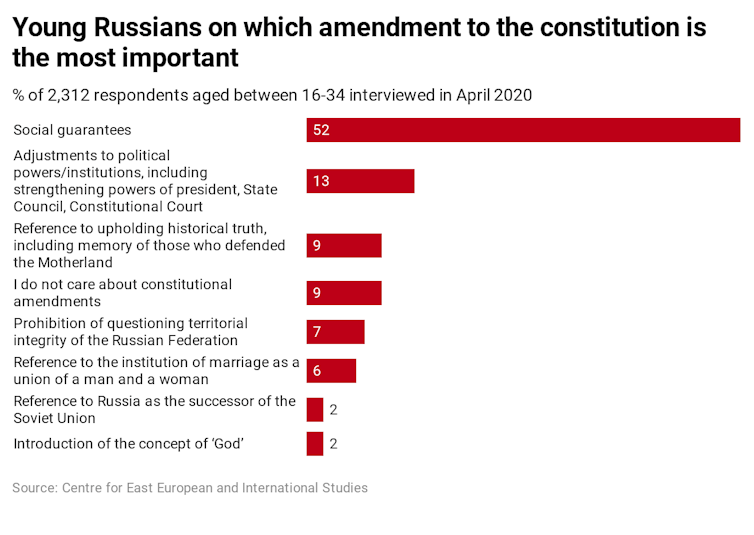

Asked what they considered to be the most important constitutional amendment, more than half of the young Russians we surveyed mentioned the social guarantees now anchored in the constitution which include the indexation of pensions and a minimum wage. By comparison, only 13% mentioned the changes to the political order including an increase in presidential powers.

When respondents were asked directly whether they wanted Putin to step aside in 2024, a majority of 40% “fully agreed” with the proposition, and a further 26% “agreed”.

Scepticism and dissatisfaction

At the time of the survey, only 15% stated that they would vote in favour of the proposed amendments, 29% planned to vote against, and 23% stated that they would not vote. Another 33% of young Russians were still undecided, but said that they would participate. A nationwide poll conducted by Levada around the same time in April, showed that 47% of the total population were in favour of the amendments, 31% against, and 22% undecided. Our results from April suggest that Russian youth is more sceptical or alienated than the general population.

Our data are also showing that those people who were more dissatisfied with Russia’s COVID-19 response in April were less likely to say they would vote in the referendum, or in fact intended to vote against the constitutional changes.

The stakes for Putin are higher as a result of COVID-19. Declaring “victory” over the pandemic in early June as the number of infections rose steadily, his government’s decisions to go ahead with the rescheduled Victory Parade put lives at risk for a display of Russian grandeur.

The government’s referendum campaign emphasised that Russians should vote in favour of constitutional changes to help preserve an authentic and traditional Russia as the successor to the Soviet Union. The regime is more concerned about winning overall support for its changes, and has downplayed the significance of turnout. The official state narrative should suffice to deliver the desired result – if not, there are concerns that the results could be manipulated to fit the Kremlin’s agenda. Nevertheless, the cracks in the Russian social contract are growing larger, in particular as the socio-economic consequences of the coronavirus crisis begin to hit home.

Félix Krawatzek is a senior research fellow at the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS).