In Russia, where there is no correlation between the results of parliamentary elections and the makeup of the government, the parliament has become a dormant institution. This is the term in political science for structures and formats that are envisaged by the law but do not operate in reality, because actual power and decisionmaking is based elsewhere, in institutions that are wide awake (the special services, armed forces, or presidential administration), during extracurricular activities (in the sauna, at the gym, or in hunting lodges), or through some combination of the above. The Russian parliament, which neither appoints ministers nor manages the budget, is a classic example.

Dormant institutions tend to wake up when personalist power—not necessarily the power of an individual, but power based on informal practices and personal relations—grows weak for any reason. Such institutions do have certain powers, it’s just that those powers had been forgotten. A case in point was the Fascist Grand Council, which suddenly replaced Italy’s Benito Mussolini in 1943.

A trend of formal institutions gaining power and informal institutions losing it can be discerned in Russia’s autumnal autocracy, an aging regime that abides by the well-known formula of 20 percent violence and 80 percent propaganda. Despite all the talk of a court, courtiers, and a small select group of decisionmakers, and despite the image of President Vladimir Putin as czar on the cover of the Economist, we are in fact seeing the presidential administration wither, at the very least in terms of domestic policy.

The State Duma is gearing up, Putin’s former bodyguard Alexei Dyumin is not shaping up to be an heir apparent after all, old friends like Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin are suffering from the limelight of litigation, and those who have official positions and authority rather than “access” and “informal influence” are feeling more optimistic about the future following next year’s presidential election.

One might hypothesize that this trend will continue in the next stage of regime transformation: players whose functions and clout are legislatively mandated will enjoy a more stable position, and later this will be true of players who have a media presence and can count on or at least claim public support and electoral results (in elections that might not be particularly fair or competitive, but at least satisfy some basic requirements of “legitimacy,” in the way that our political leadership interprets it today).

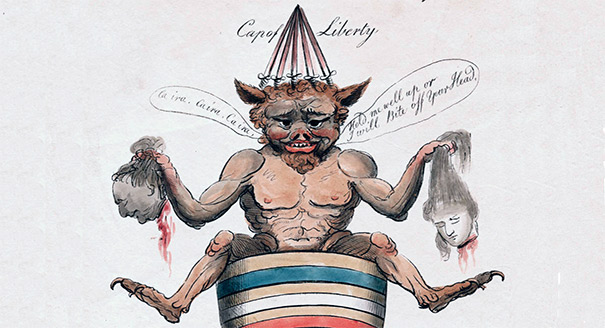

Today’s political machine is in a low-resources state, operating in calorie-conservation mode, preoccupied with survival rather than expansion. This mode does not preclude random aggressive actions (that are perceived as defensive by those within the system), and it explains the sustained—and occasionally escalating—level of rhetorical aggression. In a world where the border between words and actions is becoming blurred, the approach of “if we can’t bite, we’ll bark them away” at first looks like an appealing method of making a deep impression with a small budget, but in the long run brings the same kind of losses that a real offensive using unsuitable means would: this is just what Russia’s alleged interference in various elections boils down to.

This state of affairs makes any consistent course of reforms impracticable, whether isolationist or liberal, market or anti-market. The expected problem of low voter turnout and abstention in next March’s presidential election forced Putin to delay the announcement of his candidacy until the last possible moment, because voters would lose interest in the election the moment his participation was announced (“everything is decided!”), and the ruling class would treat the election as a done deal and start focusing exclusively on the next political cycle.

This state of the system and society prevents Putin from presenting any sort of coherent program, not to mention a reform program. The program can only be a compilation of good deeds targeting particular troubled segments that the system is able to identify. For example, the regions are deep in debt, families with children don’t have enough money, the birth rate has been declining since mid-2014, and the aging population is worried about healthcare. What we can expect is not a plan for transformation, but a regurgitation of the president’s televised phone-in shows from recent years.

The fact that the political system lacks the vitality and energy for reforms does not necessarily mean that reforms will not occur. The significance of two heavily mythologized concepts is frequently overstated: political will (the idea that if the boss man really wanted to do something, he would put the pedal to the metal, but he just isn’t really interested), and the readiness of elites for reforms.

Political elites enjoy the best possible social status by virtue of their position, and by definition cannot want change. They can only feel or imagine threats to their position and act on the basis of their perception of these threats. Political players fail to understand the significance and consequences of their actions not because they are particularly stupid, but because they exist within the system, which restricts their field of vision, while their actions are determined solely by a short-term horizon agenda.

Worse still, it is not authoritarian but totalitarian political regimes that have the resources and capacity to create and implement global plans for transformation. Democratic politicians are more concerned with dodging their opponents and appealing to voters in the next electoral cycle. Predictably, democracies steer mankind forward, whereas the colossal jumble of totalitarian plans inevitably leads to mass burial sites to be excavated by astonished descendants.

Long-term planning therefore shouldn’t be viewed in absolute terms, even if it’s reform-minded. In a recent article, political scientist Daniel Treisman analyzed 201 cases of democratization in political regimes between 1800 and 2015, studying more than one thousand history books and articles, research papers, memoirs, diaries, and online materials. He found that democratization was the result of the government’s deliberate curtailment of its powers (what one might call “liberal reforms”) in 4 percent of the cases and a consequence of a pact by the elites in 16–19 percent, whereas 64–67 percent of the cases reflected what Treisman described as “democracy by mistake.”

What were these mistakes? The regimes took steps that were intended to increase their authority, but instead weakened it: dictators underestimated the strength of the opposition, or failed to make compromises or carry out repressions at the right time, and lost their power (13–17 percent of the cases); they tightened the screws too drastically, with excessive repressions fueling protests that overthrew the regime (12–15 percent); they scheduled elections or referendums that they expected to win, but something went wrong (24–29 percent); or they started military conflicts that they lost, forfeiting power as a result (6–9 percent). One fairly common scenario is some sort of perestroika, when there is a plan to merely tweak the system, but the process spins out of control and a change in the regime or the political formation occurs.

It is notable that intentional democratization was more common in cases from before 1927. This is logical: at that level of socioeconomic development, the democratic political system wasn’t such a universal requirement, and the reformers were ahead of history. Today’s conservationists, reconstructionists, and guardians are being propelled by history itself, regardless of their own understanding of the significance and objectives of their activities.